Irish Americans have, for the most part, always thought of F. Scott Fitzgerald as the golden boy they could never claim; part Irish, so goes the common wisdom, that was exactly the part he didn’t like.

But Scott’s Celtic heritage did not cripple him, as some have asserted, nor did he deny it as he entered society’s top strata, then crashed down and cracked up. He carried his Irish blood differently at different times: cursed it, glorified it, flaunted it and (worst of all) almost forgot it. But as always with Fitzgerald and many times with the Irish — the truth is far more interesting than the legend.

“I am half black Irish and half old American stock,” he wrote to John O’Hara in 1933. The black Irish came from his mother Molly’s side; her father, Phillip Francis McQuillan, emigrated from Fermanagh in 1843, became a wholesale grocery dealer, and by the age of 40, was a very rich, very sick man. Dying at 43, he was eulogized in the St. Paul papers as a kind of immigrant epitome:

“He came here a poor boy with but a few dollars in his pocket, depending solely on a clear head, sound judgment, good habits, strict honesty, and willing hands, with strict integrity as his guiding motive. How these qualities have aided him is shown in the immense business he has built up, the acquisition of large property outside, and the universal respect felt for him by the businessmen of the country, among whom probably no man was better known or stood higher.”

The Irish side, then, not “old stock,” had the money, money the Fitzgerald family would be forced to live on when Edward, Scott’s father, proved himself a miserable failure in business. Fitzgerald wrote in the same letter to O’Hara: “The black Irish half of the family looked down upon the Maryland side of the family, who had, and really had, that certain series of reticences and obligations that go under the poor old shattered word “breeding” [modern form “inhibitions.”]”

The American side, though strapped for money, provided young Scott with Congressmen, members of colonial legislatures, and, of course, Francis Scott Key, who wrote “The Star Spangled Banner,” as ancestors: a patriotic, influential family. The McQuillans countered with a streak of the eccentric. “Whatever came into her head,” an in-law said of Molly McQuillan, “came right out her mouth.” Arthur Mizener, Scott’s biographer, adds this detail: “She was capable of appearing at a formal occasion wearing one old black shoe and a new brown one, on the principle that it is a good idea to break in new shoes one at a time.”

Knowing nothing of his Irish ancestry (there is still no adequate information on it beyond his grandfather), Scott grew up idealizing his Fitzgerald and Key forefathers while eating McQuillan bread. The Fitzgeralds were the noble past, the McQuillans the money-mad present, small town Carnegies who supported and condescended to his failed father, a man “lost … in a changing world,” as Fitzgerald put it. He never really forgave the world for changing in that way, or the McQuillans for representing it, for paying the bills and calling it a success.

And so he called that half of him “straight 1850 potato-famine Irish,” straight meaning without ambitions or distinctions outside of escaping poverty. (Scott, though he played Socialist for the last part of his life, always disliked the poor, for being poor.) “It depresses me inordinately,” he wrote of his Celtic heritage to Edmund Wilson, “I mean gives me a sort of hollow cheerless pain.” These were the times when his Irish blood ate into him.

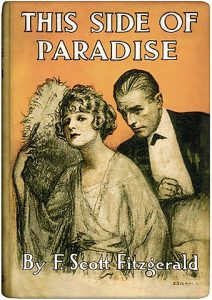

But in the autobiographical novel that splashed him onto the literary scene, This Side of Paradise, his alter-ego, Amory Blaine, is introduced as “Amory, son of Beatrice [O’Hara],” and the book begins, “Amory Blaine inherited from his mother every trait, except the stray inexpressible few, that made him worthwhile. “These include the genetic traits: “Amory became 13, rather tall and slender and more and more on to his Celtic mother.” Fitzgerald like Amory was as vain at an early age as members of the species get, and so this statement is not a casual one: he “took” after Molly and the McQuillans in more ways than one.

Early on in this most “Irish” of Scott’s novels, there is a moment that many people find confirms their suspicions of Scott’s loyalty to his heritage. Amory, age 13, is plotting the seduction of a playmate and imagines himself, crucially, as being “awful good-looking” and “English, sort of.” The moment passes, and he gets the girl without declaring himself either Celt or Anglo Saxon, but it still must be counted as indicative of his early shame at being Irish, a belief that in the world he wanted to enter, it was not nearly good enough.

The book obviously broke open for Scott a whole new range and depth of Irish types: mystics, patriots, dreams, and artists.

This changes, in the novel, when Amory meets Monsignor Darcy. “He was rather skeptical about being an Irish patriot—he suspected that being Irish was rather common-but Monsignor assured him that Ireland was a romantic lost cause and Irish people quite charming and that it should be, by all means, one of his principal biases.” It would be hard to imagine a less stirring or sincere discovery of the worth of one’s roots—the sentence begs to be spoken in prig-English: “rahlly,”“quite chahming,” “by all means,” “prin-cipal biases,” old chap, etc, etc.

It’s wrong enough to be hilarious, in a way, but also enormously depressing in another—in that it shows Amory / Fitzgerald as a phony, a user. But, in Fitzgerald’s life, the later discovery—that being Irish could be a reason for pride, a matter of celebration–was a real one.

He met Father Fay, the model for Monsignor Darcy, in 1909, and through him, Shane Leslie, son of an Anglo-Irish baronet, who had converted to Catholicism. Not only did they “make of the Catholic Church a dazzling, golden thing, dispelling its oppressive mugginess, giving [it] the romantic glamour of an adolescent dream,” they did much the same thing for Ireland. In fact, they stirred him to a small act of social bravery. In May of 1917, Fitzgerald reviewed Leslie’s book, The Celt and the World, in Princeton’s Nassau Literary Magazine, the prominent journal where he hoped to make his literary name. He wrote: “The Celt and the World is a sort of bible to Irish patriotism…To an Irishman, the whole of the book is fascinating. It gives one an intense desire to see Ireland free at last to work out her own destiny under Home Rule. It gives one the idea that she would do it directly under the eyes of God and with so much purity and so many mistakes. It arouses a fascination with the mystical love and legend of the island which “can save others, but herself she cannot save….”

He [the reader] will read an engrossing view of a much-discussed race and decide that the Irishman has used heaven as a continued referendum for his ideals, as he has used earth as a perennial recall for his ambitions.”

“To an Irishman,” to me, he was writing. What was in This Side of Paradise a pose becomes, in the real life of a painfully status-conscious boy at powerfully status conscious Princeton, a small one-man uprising. In Leslie’s affirmation of the “mystical Celt,” Fitzgerald must have rejoiced, and in the romantic figure of the handsome intelligent author, he must have at last found a wholly different Gaelic model from Grandfather McQuillan who, for all his hard and honest work, was inadequate as an ideal for his artistic grandson.

The entire review is fascinating for several reasons. First, it shows that Fitzgerald was reading not only Leslie but also other contemporary Irish writers: Synge, Yeats, and Lady Gregory. And the book’s theme, as Robert Sklar puts it, “distinguishing between two major races in Aryan civilization, the Celt and the Teuton, the one [being] mystical in nature, the other material,” revealed to Scott that the ultra material McQuillans were not, in any sense, fully representative of the Irish or their past.

The book obviously broke open for Scott a whole new range and depth of Irish types: mystics, patriots, dreamers, and artists.

Finally, there are premonitions of Fitzgerald ‘s great themes not only in the book, but in the reviewer’s reaction to it: the “unworldliness” in the face of “the futility of man’s ambitions” is one of Leslie’s qualities that Fitzgerald finds remarkable, and his sense of tragedy (though it is called “pessimism” here), “What doth it profit a man if he gaineth the whole world and loseth his own soul” is one that colors The Great Gatsby as well as The Celt and The World. Leslie gave Fitzgerald a heightened sense of two things: his Celtic identity and Celtic tragedy.

After his most entertaining End of a Chapter, Mr. Leslie has written what I think will be a more lasting book. The Celt and The World is a sort of bible to Irish patriotism. Mr. Leslie has endeavored 10 t race a race, the Breton, Scotch, Welsh, and Irish Celt, through its spiritual crises and he em phasiz.ts the trait that Synge, Yeats. and Lady Gregory have made so much of in their plays, the Celt’s inveterate mysticism.

The theme is worked out in an era-long contrast between Celt and Teuton, and the book becomes ever-ironical when it deals with the ethical values of the latter race. “Great is the Teuton indeed,” it says, Luther in religion, Nietzche in philosophy, Rockefeller in oil, Cromwell and Bismarck in war.” What a wonderful list of names! Could anyone but an Irishman have linked them with such damning significance?

In the chapter on the conversion of the Celts to Christianity, are traced the great achievements of the Celtic priests and philosophers, Dungal, Fergal, Avelord, Dus Scotus, and Evergena. At the end of the book that no less passionate and mystical, although unfortunate incident of Pearse, Plunkett, and the Irish Republic is given sympathetic but just treatment.

To an Irishman the whole of the book is fascinating. It gives one an intense desire to see Ireland free at last to work out her own destiny under Home Rule. It gives one the idea that she would do it directly under the eyes of God and with so much purity and so many mistakes. It arouses a fascination with the mystical lore and legend of the island which “can save others, but herself she cannot save.” The whole book is colored with an unworldliness and an atmosphere of the futility of man’s ambitions. As Mr. Leslie says in the foreword to End of a Chapter (I quote inexactly), we have seen the suicide of the Aryan race, “the end of one era and the beginning of another to which no Gods have as yet been rash enough to give their names.”

The Celt and The World is a rather pessimistic book: not with the dreary pessimism of Strindberg and Sudermann, but with the pessimism that might have inspired “what doth it profit a man if he gain eth the whole world and loseth his soul.” It is worth remarking that it ends with a foreboding prophecy of a Japanese-American War in the future. The book should be especially interesting to anyone who has enjoyed Riders to the Sea, or The Hair-Glass. He will read an engrossing view of a much-discussed race and decide that the Irishman has used heaven as a continued referendum for his ideals, as he has used earth as a perennial recall for his ambitions.

His very next story for The Nassau Literary Magazine would center around the speech (about life, death, war, the Germans. and religion) an Irish soldier delivers as he dies. And Fitzgerald would review Leslie’s next book (poetry), calling him “an Irish Chesterton.”

This Irish cry in the WASP wilderness of Princeton —”I am what I am!” as we now say it—bubbles back into the novel in important ways. Fitzgerald names two of his Princeton heroes “Burne and Kerry Holiday” in the novel (the men he based them on were not Irish). He quotes extensively from the letters of Fr. Fay, with their Gaelicisms galore. But that exultation brought with it a problem.

Monsignor Darcy writes to Amory:

“Do you remember that weekend last March when you brought Burne Holiday from Princeton to see me? What a magnificent boy he is! It gave me a frightful shock afterward when you wrote that he thought me splendid; how could he be so deceived? Splendid is the one thing that neither you nor I are.

We are many other things—we’re extraordinary, we’re clever, we could be said, I suppose, to be brilliant. We can attract people, we can make atmosphere, we can almost lose our Celtic souls in Celtic subtleties, we can almost always have our own way; but splendid—rather not!”

This is, with the exception of the first sentence and one key phrase, “we can lose our Celtic souls in Celtic subtleties,” quoted directly from Father Fay’s letter to Scott of December I0, 1917. Though Fitzgerald could give the Irish name “Burne” to the character whose real-life version was named Henry Strater, a Princetonian who led a rebellion against the eating clubs there, he could not help interjecting into Fay’s reasons for not being “splendid” one of his own: the Celtic soul.

Though he (and Father Fay) connected the qualities of charm, wit, and personality (“we can attract people”) with Irishness, the idea of splendidness, of a kind of heroic and vital authenticity, seemed to Scott to lie beyond it. We find the same idea in his letter to Mrs. Richard Taylor (1917): “Updike of Oxford or Harvard says, “I die for England” or “I die for America”—not me, I’m too Irish for that; I may get killed for America, but I’m going to die for myself.” His Irish blood both confirmed his uniqueness, especially as a “personality,” even as it isolated him, set him apart, giving him a distrust of principles his peers embraced. Indeed, the man he most admired at Princeton is described as a real “Updike of Oxford,” he looks “like those pictures in the Illustrated London News of the English officers who had been killed.” Yeats said it best:

“The best lack all conviction, While the worst are filled with a passionate resolve.”

Thus the Irish were, to Scott, the best.

Fate and the world consistently denied him the chance to prove that his “Celtic soul Jost in Celtic subtleties” would rise to a communal action with conviction; in This Side of Paradise, he sends Amory off to war with a poem (lifted from a Fr. Fay letter) echoing in Gaelic:

“Ochone

He is gone from me the son of my mind

And he in his golden youth like Angus Oge…

Aveelia Vrone

His hair is like the golden collar of the Kings of Tara

And his eyes like four gray seas of Erin.

And they swept with mists of rain.”

But there are to be no battle scenes in the book; Fitzgerald never saw action. Instead, he met and courted Zelda Sayre, his future wife, in the territory of Montgomery, Alabama. He made love and not war.

At the end of This Side of Paradise Fitzgerald writes: “Between the rancid accusations of Edward Carson and Justice Cohalan, [Amory] had completely tired of the Irish question, yet there had been a time when his own Celtic traits were the pil ars of his personal philosophy.” Not meant to be funny, like so many of Amory’s reactions to the world, it is. The “Irish question” is hardly to be found in the novel before Amory “tires” of it, and as for “pillars of his personal philosophy,” Amory has neither. By the time he was writing this, Fitzgerald wanted to be a serious man; at the very end, Amory goes suddenly and hilariously socialist—becomes a man of ideas.

Thus, Fitzgerald tosses his “Celtic traits” of wit and charm and fierce, skeptical individualism overboard, and Amory begins to think of himself as the kind of man who is built on pillars of personal philosophy. We are meant to believe that Amory’s Irishness went the way of his “lost youth.” Those two ideas become intimately connected, then, at the end of Fitzgerald’s first, and as I said, (and if you want to call it that) “most Irish” novel. In fact, the former idea, the self-awareness of the writer as Irish, became, in a way, a subdivision of the latter idea.

Though Fitzgerald, looking back, packing up, moving on at the end, of This Side of Paradise, claims to leave the Celt behind, what his friend Edmund Wilson observed, writing in 1922, remains true for all his work:

“The second thing one should know about him (the first was that he hailed from the West) is that Fitzgerald is partly lrish and that he brings both to life and to fiction certain qualities that are not Anglo-Saxon. For, like the Irish, Fitzgerald is romantic, but also cynical about romance; he is bitter as well as ecstatic; astringent as well as lyrical.

“He casts himself in the role of a playboy, yet at the playboy he incessantly mocks. He is vain, a little malicious, of quick intelligence and wit, and has an Irish gift for turning language into something iridescent and surprising. He often reminds one, in fact, of the description that a great Irish- man, Bernard Shaw, has written of the Irish: “An Irishman’s imagination never lets him alone, never convinces him, never satisfies him; but it makes him that he can’t face reality nor deal with it nor handle it nor conquer it: he can only sneer at them that do … and imagination’s such a torture that you can’t bear it without whiskey…And all the while there goes on a horrible, senseless, mischievous laughter.”

“Bitter as well as ecstatic,” “astringent as well as lyrical,” describes not only Scott’s Celtic turn of mind, but, in turn, the way he, Celtically, came to feel about it. And Shaw’s dead-on description of the Irishman’s curious isolation reminds us of Fitzgerald’s sense that he was fighting a war no one else was, apart from the “Updikes” who were dying for England and for America.

In his next novel The Beautiful and Damned, there are the faintest traces of interest in the changes Irish America was undergoing at the beginning of the century: “Irish girls were casting their eyes, with license at last to do so, upon a society of young Tammany politicians, pious undertakers, and grown-up choirboys.” But the interest is never consummated; this miserable “sociological” novel a failure in almost every respect fails too in its portrayals of immigrants (unless you agree that immigrants are astonishingly dirty and stupid). We have, on page 425, “a greedy Mick” earned Halloran, and this cameo of an Irish servant: “They tolerated rather than enjoyed the services of a gaunt, big-boned Irishwoman, whom Gloria loathed because she discussed the glories of Sinn Fein as she served breakfast.” Scott had really tired of the Irish question by this time. But if the Irish American reader wanted to file a complaint, he would have to stand behind the Polish American, Greek American, Japanese American, and literate Americans in general.

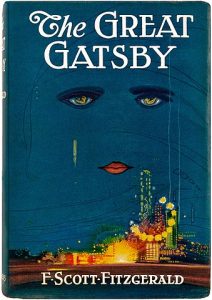

With The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald retells the story—transformed and fortified by his art at the height of its powers—of his grandfather McQuillan, the story of the boy who rises from lowly origins to the American heights of status and power. But it is no longer—as it was, significantly, in This Side of Paradise—an ethnic story. Indeed, if we look at the famous list of people who attend Gatsby’s parties, a fictional who’s who of 1920s society, we find the Mulreadys, McCarty, Muldoon, O’Donovan, the Corrigans, Fitzpatrick, the Kellehers, the Scullys, the Quinns, McLenahan and O’Brien.

The Irish, like Gatsby, like Fitzgerald himself, had made it: the various hungers of the immigrant had been satisfied and the prices paid. Though the ethnic element is present, it lies in the background, the past of this novel-against which questions about lost hope, youth, and possibility are drawn, and ultimately answered.

The last Celtic mention in Fitzgerald’s novel occurs in the last complete one, Tender is the Night. The hero, if he could be called that, whose name is Dick Diver, is described by the young actress who falls helplessly in love with him:

“His voice, with some faint Irish melody running through it, wooed the world, yet she felt the layer of hardness in him, of self-control and self-discipline, her own virtues.”

To the “Celtic traits” of his youth are added those things life had taught him, or rather, demanded he learn: self-control, and self-discipline. The wild rhythms of This Side of Paradise are gone, “a faint Irish melody” remains. He had never become splendid—brilliant, English, and fatally heroic—but he now resembled, in this prose portrait, a wild colonial boy with large and serious convictions, a sobered view of life, a less sparkling personality. Which Fitzgerald had, essentially, become.

“The Irish Scott” does then exist, and not as a study in self-denial. Fitzgerald hated what he considered his wholly unromantic Irish past, having no adequate Celtic models until he met and read Shane Leslie—in which to witness the kind of jack-hammer vitality, the gift of lyric language, the wit and glow that he found in himself. Once he met Leslie and Father Fay, he honored and reveled in his lrishness, celebrated it, and recognized it (when he agreed with Edmund Wilson’s essay) as a major facet and source of his talent; he did, in fact, sign his letter to Wilson, for a period, “Celtically,” and “Gaelically yours.” He also backlashed against it, especially in times of violent self-doubt, as his “straight 1850 potato-famine” heritage was one of the causes of that doubt.

Finally, we can say this: Fitzgerald considered his Irish heritage one of the things that made him distinctive as an individual and a writer, and he considered himself, for better or worse, Celtic and American at heart. ♦

Excellent! I have read Gatsby only, but this piece motivates me to read more Fitzgerald.