The Irish who built the Empire State Building and the photographer who captured the work.

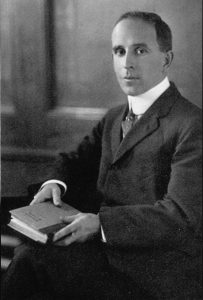

In 1908, acclaimed photographer Lewis W. Hine snapped a simple portrait entitled “Irish Steel Worker.” The aged laborer has a weathered face and sad eyes. A pipe sprouts from his mouth. He sports suspenders, a thick handkerchief in his front pocket, and a woolen cap atop his head.

Hine, born in Wisconsin in 1874, would go on to become one of the progressive era’s great photographers. As Jacob Riis did a generation earlier, Hine used the camera as a tool to record social inequities and spur reform.

The same year he snapped the Irish steel worker, Hine also created one of his more famous series of photographs, entitled “Child Labor: Girls in Factories.”

But it was a decade and a half later that Hine would find his true muse. Hine’s most famous subject was not even a person. It was, instead, the tallest building in the world, a monument to enormity and audacity which just so happened to begin rising as the nation sank into a deep depression.

Laborers and Power Brokers

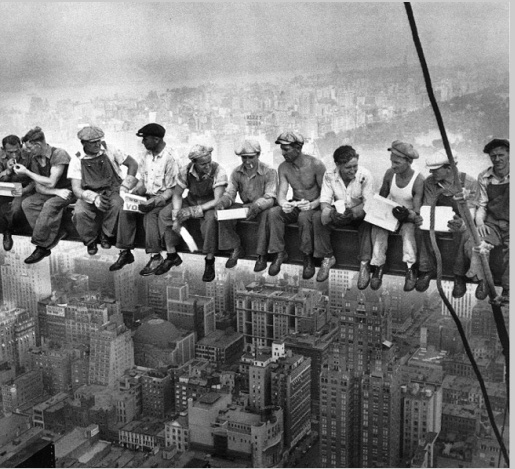

Hines photographs of the Empire State Building (as well as his famous portrait of Chrysler Building laborers perched above the city eating lunch) capture the wonder, romance and artistry of the skyscraper and its builders. Almost as an afterthought, though no less important, the photos also capture a project on which Irish Americans played a central role, from the power brokers who envisioned this unprecedented project to the laborers who got the Empire State Building erected in just one year.

At the ground level, Hine captured the determination of the men who stirred the concrete and stacked the steel. But it’s important to note that Irish American power brokers also played a key part in the Empire State Building’s rise.

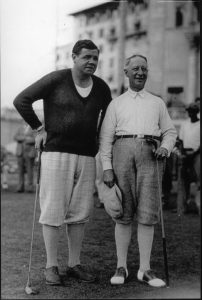

First, there was Al Smith. A child of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Smith often claimed the only degree he ever earned was an FFM degree, because he had to go to work at the Fulton Fish Market when his father died. Smith emerged from Tammany Hall in an unlikely fashion: without the whiff of corruption. He served as a popular, progressive New York governor in the 1920s, but then made a doomed run for the presidency in 1928.

Smith was the first Catholic candidate to run for the White House and many in middle America considered Smith an agent of Rome who hailed from the mongrelized metropolis. The Ku Klux Klan burned crosses on the election trail. Even Smith’s opposition to prohibition was seen as deeply unsavory. Add in the fact that economy was booming and you get the picture. Smith was trounced by Herbert Hoover.

Raskob the Irishman

Though it devastated him, Smith did not vanish into obscurity after this loss. He was named president of the Empire State Building Corporation, whose job it was to erect a towering new building on the former site of the midtown Manhattan Waldorf-Astoria hotel.

Another important figure in the planning stages of the Empire State Building was John J. Raskob. Raskob’s father was Alsatian, but his mother was Irish Catholic. The self-made man from Lockport, New York first got a job with the Du Pont family in the early 1900s and made enough money to invest in Manhattan real estate just in time for the roaring 1920s.

On August 29, 1929, Raskob, Smith and a group of investors took aim at the biggest real estate investment New York had ever seen: The Empire State Building.

Less than two months after this announcement, the stock market crashed. Raskob, Smith and the other big wigs who saw dollar signs at the vast corner of 34th Street and Fifth Avenue would have to adjust their vision. The Empire State Building would still go up. The problem? It might turn out to be the biggest real estate boondoggle in American history.

Still, the project was good news for at least one group of people; Irish American laborers desperate for work. Men like Irish immigrant Michael Briody.

A “Novel” Approach

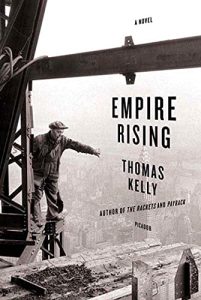

Laborer Michael Briody would probably be forgotten had he not been New York Irish novelist Tom Kelly’s great uncle. Kelly had heard family stories about his uncle. Briody got mixed up in some shady business, was murdered and buried in the Bronx. Kelly decided to look more deeply not only into his uncle’s past but into the celebrated skyscraper he helped build. The result was his thrilling 2005 novel Empire Rising. Though it is a work of fiction, Empire Rising is a rich, informative look at how the Irish helped build the Empire State Building.

There are no hard statistics about just how many Irish immigrants and Irish Americans helped build the Empire State Building. But it is generally accepted that Irishman, as well as Scandinavian Americans, were the dominant group at the work site.

One reason for this is because a new wave of Irish immigrants had swept into New York City. As with the Irish immigrants (such as Mike Quill) who founded the Transit Workers Union (TWU) in 1934, more than a handful of Empire State laborers were Irish Republicans on the run from the grueling civil war which broke out in Ireland in the 1920s, following the Easter Rising and partition.

For these Irish immigrants — who fled a war-ravaged land just in time to hit a great depression in the U.S. — a job on a project such as the Empire State Building seemed a blessing from the sky. It was a chance to put the past behind them and help create an American icon.

Unbeknownst to all of the men who were working on the Empire State Building, a man with a camera was documenting them. Just as he’d been documenting laborers and immigrants for the previous 30 years.

Men of Steel

This famous photograph taken by Charles C. Ebbets during the construction of the GE Building at Rockefeller Center in 1932, shows 11 men eating lunch, seated on a girder with their feet dangling hundreds of feet above New York City. Many attempts have been made to identify the man several of whom are Irish laborers. According to a recent story in The Connacht Tribune, the picture features two men from Shanaglish, near Gort, County Galway. The man on the extreme left of the photo lighting the cigarette is Matty O’Shaughnessy while Patrick ‘Sonny” Glynn is holding the bottle on the extreme right. The photograph has appeared on many book covers, including Peter Quinn’s Waiting for Jimmy, and an edited version on the Sawdoctors’ album entitled To Win Just Once…The Best of the Sawdoctors.

Hines at Ellis Island

Lewis Hine was in his late 20s, and only in New York City for a few years, when he and his camera were drawn to Ellis Island in the early 1900s. The Irish were still coming (such as the laborer whose memorable portrait he took in 1908), but these were also the days of the so-called “new” immigration. Waves of Italians and Jews from Eastern Europe were arriving every day at Ellis Island, along with Finns, Germans, Poles and Hungarians. From 1904 to 1909, Hine documented the hardships as well as the happiness, mystery and daily grind of the Ellis Island immigration process.

It was the first of many progressive photographic projects for Hine. Born in the progressive hotbed of Wisconsin, Hines political outlook was further honed at the University of Chicago. He brought this belief in progress and reform to New York in 1901. He became a teacher at the Ethical Culture School and, according to biographies, took up the camera around this time, believing that images could be as powerful, if not moreso, than words.

Following his Ellis Island series, Hine’s photos of child laborers opened many eyes and were part of a broader movement to expose and put an end to the use of child labor. By this point, Hine’s work was coming to be considered not just crusading but sociological. His portraits were studied for all that they revealed about their subjects. He photographed conditions in Europe for the Red Cross after World War I, then returned to Ellis Island in the 1920s to document efforts to improve conditions at the immigration center.

Then, in March of 1930, just seven months after Smith and Raskob announced the construction of the Empire State Building, Hine was commissioned to document the skyscraper’s rise.

Man and Machine

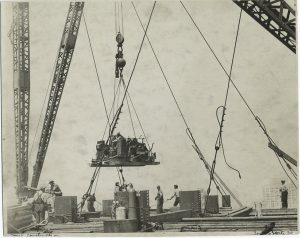

The men in Hine’s photos of the Empire State Building are lean, muscular. Often they seem to be floating, even dancing gracefully. Of course, they are actually a slip of the hand or foot from death. (Interestingly, it is believed that only five people died during the construction of the Empire State Building.)

In Hine’s photos, the sun and sky create stark contrasts of black and white. The steel and machinery often seems to gleam, in contrast with the hazy, seemingly insignificant buildings in the distance. The photos ultimately capture the awe such a skyscraper, and its construction, inspired in the 1930s, a feat difficult for modern audiences to grasp, now that nearly every medium-sized city in the word has skyscrapers.

In the end, Hine, Smith, Raskob and the Irishmen who helped erect the Empire State building produced a collaborative work of art. Of concrete and steel, shutter and lens. When the tin towers were destroyed in 2001, the sight of the Empire State Building was, among many other things, a beautiful comfort. For it too had had its plane crash. On July 28, 1945, a U.S. Army B-25 bomber lost in the fog hit the 79th floor causing 14 deaths and $1 million in damages. But the building stood and continues to function as an office building and the main tourist attraction in New York City.

When deciding what the first line of Empire Rising should be, Tom Kelly ultimately chose this very telling line: “This one, they say, will stand forever.”

https://youtu.be/EdDECW5FLAM

Happy Labor Day!

My grandfather, John Granton and my Father, James Granton worked side by side as Iron Workers for over 30 years. As a family we are proud.

Perhaps the most unique aspect of the New York City area is the architectural design and dimension of the city infrastructure. “How high can a skyscraper go? .. as high as the air is breathable.” Steel can stand any strain, and the men who build these structures are as durable as the steel they work with. The motto of the Ironworkers, “We do not die; we are killed,” justifies their self-defiance when facing constant danger of injury and death.

Ellen Moore