The last few years of the great Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s life were spent with an Irishman. That Irishman was Barry O’Meara, a Dublin-born surgeon who caught the Emperor’s attention during his surrender on the British warship Bellerophon. This encounter would change O’Meara’s life, as he was personally requested by Napoleon to be his physician during his time on the island of St. Helena after Napoleon’s original physician fell ill and begged his Emperor to be dismissed.

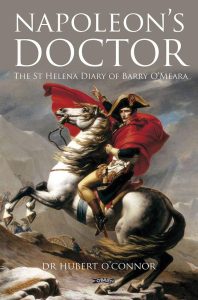

Napoleon’s Doctor: The St. Helena Diary of Barry O’Meara, by Dr. Hubert O’Connor, is a fascinating insight into one of the most influential military minds that the world has ever seen. The book is the result of 30 years of research by O’Connor, a former rugby player for Ireland and a physician himself. In it, O’Connor transitions between O’Meara’s diary and the history surrounding O’Meara’s words.

O’Connor had two goals in mind in researching and writing this book. He wanted to “attempt to vindicate the reputation of O’ Meara” and to “paint a personal picture of the Emperor and the Irishman – the great Napoleon himself on St.

Helena and the Irish doctor who accompanied him there.” These goals are admirably attained in O’Connor’s thorough project, as he mostly lets O’Meara’s diary entries do the work in showing how these two men interacted.

After the diary entries, O’Connor delves into the last days of Napoleon’s life, O’Meara’s return to London, and the journey Napoleon’s body took from St. Helena back to France. The last chapter explores the possibility of Napoleon being poisoned by his jailers at the end of his exile. If you want an intimate perspective on the last days of a man who almost conquered the world, Napoleon’s Doctor should be right up your alley.

Chapter 1: The Irish Doctor

For over twenty years, since he first emerged in 1793 as a young artillery officer at a siege in Toulon, Napoleon Bonaparte had been the wonder and the despair of the world. His extraordinary energy had shaken the old countries of Europe to the roots-first France, then Italy, Germany, Spain, Portugal, not to mention Egypt, Russia and Syria-none would be the same after his passing through. By 1814, however, his enemies had been too much for him and he was incarcerated in the Mediterranean island of St Elba, not far from his Corsican birthplace. The diplomats of Europe packed their bags and prepared for a long and enjoyable session of haggling and self-indulgence at the Congress of Vienna. But they had not heard the last of Napoleon.

Aided by devoted adherents, he escaped from Elba in early 1815 and drove north to Paris, gathering more and more enthusiastic supporters as he went. This mesmeric power over the ordinary French people was his strength, not least because it was by far the most populous country in Europe-24 million people against Britain’s 10 million and Ireland’s 5 million (Germany and Italy were still divided into small states).

Europe quickly declared war against him, and eventually fought him to a stop at Waterloo. What Wellington famously called the ‘near-run thing’ cost 40,000 French, and perhaps 22,000 Allied soldiers’ deaths. Napoleon was soon forced to abdicate a second time.

This time the Allies were taking no chances. The most dangerous man in Europe had vividly shown his power during the hundred days since his escape from Elba, and they, particularly the British, were going to make sure that would not happen again. They identified one of the most remote islands in the world, a tiny victualling post in the middle of the southern Atlantic used by ships travelling to and from India. That was to be Napoleon’s new place of exile. Furthermore, the island was going to be policed by as many ships and soldiers as might be necessary to ensure that any escape plans, such as those mooted by Bonapartist refugees in America, should come to nothing.

On board, the Bellerophon, the ship used to transport Napoleon and his entourage away from France, was a young Irish surgeon, Barry O’Meara, who was about to embark on the adventure of a lifetime. We join O’Meara on the first leg of the long voyage from Europe to Napoleon’s prison-island, thousands of miles away.

Late in the afternoon, the doctor came on deck for fresh air. The heavy Atlantic swell had made most of the new passengers quite seasick. He had spent many hours in the stifling heat below, tending to those who were ill. It was now a beautifully blue, cloudless evening and there was a moderate fresh breeze. With the measured step of an experienced seaman, he made his way up to the poop deck, where he joined a small group of his fellow officers.

The conversation turned inevitably to the dramatic events of the previous days. Suddenly all those facing the stern stood to attention and removed their caps. The doctor turned and saw the Emperor coming toward them. He was accompanied by marshals and generals but, even though they surrounded him on all sides, there was still the sense of a respectful distance being observed. As one of them recalled later, although obviously a prisoner, ‘Napoleon was in fact still an Emperor aboard the Bellerophon. The captain, officers, and crew soon adopted the etiquette of his suite, showing him exactly the same attention. The captain addressed him either as “Sire” or “Your Majesty”.’

After he had climbed up to the deck and nodded to the young officers to be at ease, Napoleon leaned against the rail and for a time gazed down at the clear water and then to the horizon. Eventually, turning back to the group, he noticed the doctor for the first time.

‘Are you the chirurgien major?’ he asked, addressing him in French. In Italian O’Meara confirmed that he was. In Italian also, Napoleon continued: ‘What is your native country?’ ‘Ireland.’

‘Where did you study your profession? ‘I studied in Dublin and later in London. ‘And tell me, Doctor, which is the best school of medicine? For anatomy Dublin is best. London is best for medicine., ‘Ah, you only say that because you are Irish! ‘No, no, Sire bodies are much cheaper to buy in Dublin, so our anatomy and hence our surgery is much better.

Napoleon smiled at this reply and then changed the subject. ‘Where have you seen battle? the Emperor asked quietly. ‘I have fought, Sire, in Sicily, Egypt and. more recently, in the West Indies., O’Meara told him briefly of some of the more memorable battles in which he had been involved and then, in somewhat greater detail, of the capture of the 74-gun French flagship, the Rivoli. ‘You appear to have been remarkably fortunate in your sea battles. ‘Yes.’ ‘The Rivoli was a great loss.’

Napoleon wanted to know more about Egypt and the doctor told him of the rescue of a garrison under siege in Alexandria 1807. To his surprise, he discovered that Napoleon had watered and fed his horses in the very same stable where he himself had bivouacked at Aboukir.

Napoleon laughed loudly at this, and afterward ‘recognised O’Meara when he noticed him, and occasionally called on him to interpret or explain English terms. Since one of Napoleon’s entourage was ill, O’Meara was frequently in attendance, and Napoleon regularly asked about the patient, and about the malady and the mode of cure.

From these conversations arose a trust between the two men, and eventually an offer that was to set the thirty-two-year-old doctor on a life-changing course.

Dr. Hubert O’Connor was a well-known obstetrician and gynecologist in Dublin. He played rugby for Ireland and was capped four times. After ten years of post-graduate education in France and London, he set up his practice in Dublin. He was married to Anne, and they had two children. He spent thirty years researching the history of Barry O’Meara and Napoleon and lectured on the subject all over the world. Dr. O’Connor died in 2011. Naploean’s Doctor: The St. Helena Diary of Barry O’Meara is available on Amazon.

His great-grandson also a doctor and called Barry O’Meara was the GP in Bree a village in County Wexford He died tragically young of a neurodegenerative disease

I was a next door neighbour of Barry o’Meara. He came to live beside me after getting a GPs practice there. He had one daughter Emily when he arrived and shortly after had a son Brendan and another girl Lucy. His wife Yutha Schmith was also a Dr. She was a refugee from Romania but was born in Bavaria where her parents had fled after the Russian takeover. Her Dad had a family business in the timber trade so when Faber Castell set up a pencil making factory in Fermoy he was glad to escape Germany where they were’nt welcome. I remember Barry telling me about a great uncle who lived in Bridgetown in south Wexford when he showed me a photo of him outside a shop in the small village. Barry spent 2 years at sea training to be a ships captain like this uncle but changed his career to follow his father into medicine. He had been the county Cork Chief Medical Officer but he had spent his early medical career in Galway where Barry was born. Barry was a fluent Irish speaker and set up the two Irish speaking Schools, national and secondary in Enniscorthy. My daughter Sinead’s children are students there. He was an avid Bee Keeper but sadly he and his wife were divorced before he became ill and died from motor-neuron disease. His assistant in the Bree clinic was a great help to him after he became ill and along with her sister nursed him to the end. RIP.

I am a great Fan og Napoleon Bonoparte and read as much as I can about his life. To find that my neighbour was connected to him is amazing and I hope they have become buddies in their heavenly home. Thanks alot for this info.: