I wonder if we are, as novelist Salman Rushdie has written, at the deepest level of our nature, “frontier-crossing beings.” Is it part of an innate desire to step across borders, and by doing so enter into places that can be disorienting or even dangerous? If that is so, are we not wall-builders as well, determined to keep at bay the foreign, the invader, and the impure?

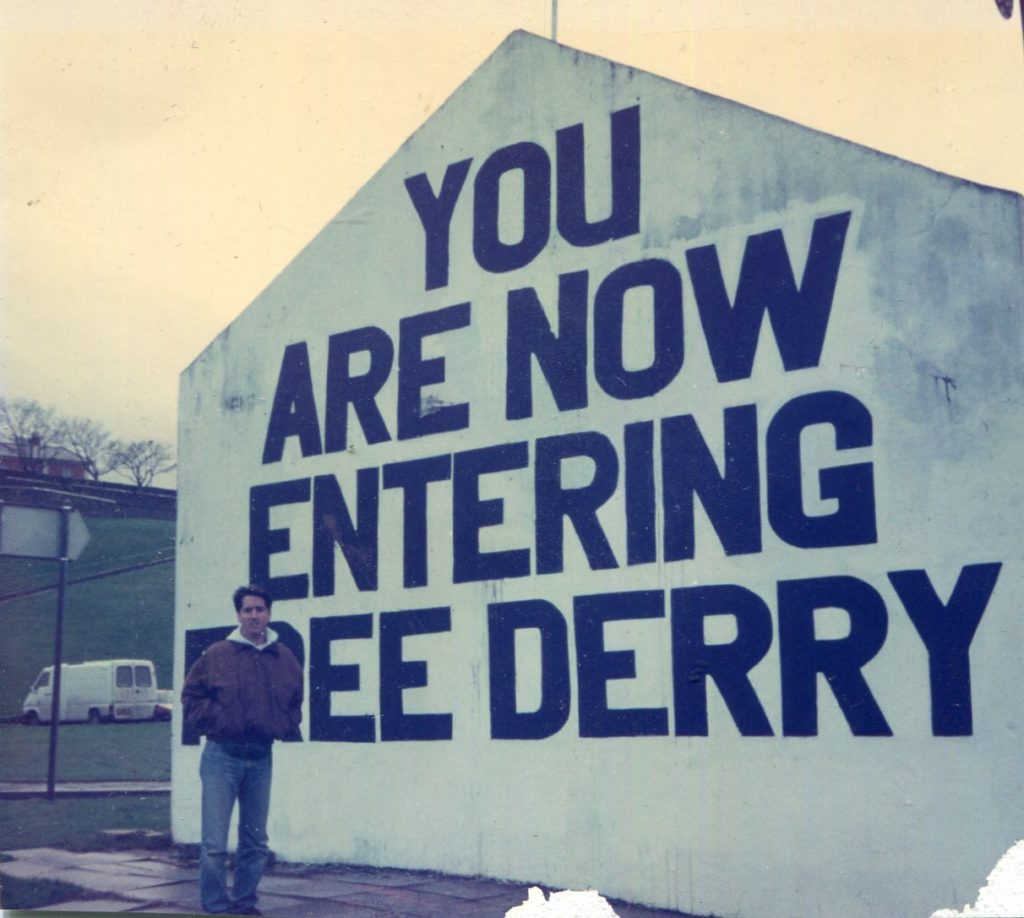

When I first traveled to Northern Ireland in 1989 to visit a close friend in Derry, I drove north from Dublin along the N1 towards Newry, a town just across the border from the Republic. It wasn’t the height of the “Troubles” – close to 500 people were killed in 1972 – but it wasn’t a time of tranquility either. Seventy-five people would be killed by the Irish Republican Army or Loyalist paramilitaries or by British troops or police by the end of the year.

Approaching the border, I saw the heavily armed British soldiers lean in car windows. When my turn came, I offered my passport to a young soldier and was asked about where I was going and for what purpose. I fixated on the black barrel of the rifle and tried not to sound nervous but my heart was pounding.

It is difficult to remember the precise feelings from that time, but reading my notes from that first trip north, it’s clear that I was struggling to get a fix on what was happening there. In contrast to Dublin, a place that I’ve always experienced as welcoming, colorful and friendly, my writings about Belfast and Derry are filled with the adjectives “brooding,” “dark,” “suspicious,” and “dangerous.” On this early journey, I was intent on knowing exactly where I was and cautious about what I said.

On my first day in Belfast, I walked along the Catholic Falls Road and the Protestant Shankill fascinated by the murals of IRA and Loyalist martyrs and the ominous “messages” the paintings delivered. People were more willing to talk in the Catholic areas, and they spotted that I was a “yank.” Many were curious about what I was doing there. In Derry, while visiting my friend, a mortar round was shot at a Royal Ulster Constabulary station (dissolved in 2001 as part of the Peace Agreement) a hundred yards from where I was staying. Young boys from across the street ran into their front yard and cheered. I thought a bomb had gone off right at the front door.

I didn’t have an axe to grind traveling to Northern Ireland, or for that matter, a feeling that I was there to contribute to a “righting” of the injustices that Catholics had suffered. While my mother was Irish – an O’Callaghan before ditching the O – I was not raised either religious or with a self-conscious Irish identity. I grew up in rural Southern California, far from the Irish American urban enclaves. I wasn’t obsessed with the British, a state that would obviously have been different had I grown up in West Belfast.

And yet, when I landed in Ireland for the first time, I felt an eerie sense of familiarity, as if the shape and range of my emotions fit perfectly into the colors and contours of the land. I reveled in the sly Irish humor that seemed pervasive. The New York writer Pete Hamill described his first trip to Ireland in a similar fashion, the hard-edged skepticism of a reporter giving way to “scrambled messages … rising from beyond the knowable world.” For Hamill, this dreamy “spiritual” experience meant that he was home.

I tried to read my way into Irishness. I began with history, reading everything I could find, starting with the Plantation of Ulster and moving forward. For a while, I was fascinated by the so-called “revisionist history” debate in Ireland, as it reminded me of similar interpretive wars over the meaning of American history that had raged through our universities and made their way into very public political skirmishes. I read every play by the northerner Brian Friel, finding authentic dramatic language that was not reducible to political sloganeering.

Years after my first visit, writing for the Los Angeles Times, I thought I’d stumbled upon a testing ground for a unified field theory of the critical issues that bedeviled modern politics worldwide. Struggles over national identity were taking place in Northern Ireland. The use of violence as a political tool and the presence of ethnic hatred as one of the elements that drove that violence was there in abundance. How would a more “integrated” world impact ideas about “pooled sovereignty” that might be part of conflict resolution? That question was playing out in real time as well.

And when the peace process started in earnest after the IRA cease-fire in 1994, the complex process of ending a conflict that had engendered so much bitterness was watched by political leaders and peace practitioners from around the world. If violence in Northern Ireland could be replaced by what Irish writer Fintan O’Toole described as the “unglamorous ambiguities of peaceful politics,” then there might be hope for other seemingly “intractable” conflicts.

I traveled to Northern Ireland at least ten times during the years it took to secure the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, including each of President Clinton’s three visits. I believed that the peace process had a good chance of success once President Clinton brought the influence of the United States into the equation by visiting Northern Ireland in 1995, and then appointing Senator George Mitchell as a Special Envoy.

I was perplexed that many of the brightest political pundits in the Republic of Ireland and Britain predicted the peace process would go nowhere. John Hume, leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party and eventual Nobel Peace Prize winner, was excoriated by many writers for reaching out to Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams, a dialogue that preceded the 1994 IRA ceasefire.

In an interview I conducted with Conor Cruise O’Brien in late 1993, he told me that “nothing would come” of the Hume-Adams talks, “not a chance.” The quest for a political solution by agreement is a “mirage,” he added. I had read O’Brien’s books States of Ireland and Passion and Cunning at the beginning of my intellectual journey and found them intelligent and challenging. He was a diplomat, an editor, a politician, and a historian, a rare combination of talents. But for O’Brien and for many other commentators, perhaps blinded by their own anger, it was as if they didn’t actually want a peace agreement if it meant that Gerry Adams was going to be rewarded with political “legitimacy.” It was a line that was psychologically – they might say politically and morally – too traumatic to cross.

In Protestant enclaves in Belfast, it was difficult for me to find “regular” people who had trust in the peace process. They seemed to have developed ingenious ways of not seeing what was taking place in front of them. One man I interviewed on Shankill Road, told me “This [peace process] is all good for Gerry Adams but a disaster for us.”

I also met resistance in Republican areas in Derry. I talked to three middle-aged men at the Telstar Bar (a place my hosts told me to steer clear of) not far from a dark green British Army watchtower that loomed over the working-class Creggan housing estate. These men, one the brother of 17-year-old Jackie Duddy who British Paratroopers killed on Bloody Sunday in 1972, were not supportive of the peace process but for reasons related to a central emotional contradiction. “If the British aren’t leaving,” one of them told me, “then what was all the sacrifice for?”

I thought of Brien Friel’s play Translations, where the character Maire responds to the yearly ritual of fear of the “sweet smell” from her hedge school classmates, a sure sign of an impending potato blight. “We’re always sniffing about … looking for disaster,” Maire says. “Some of you people aren’t happy unless you’re miserable.” In the case of Northern Ireland, the misery wasn’t caused by an innate human tendency to embrace suffering but by a seemingly crippled society’s problematic history.

In My Life, his post-presidential memoir, Bill Clinton describes his first trip to Northern Ireland in 1995 as “two of the best days of my presidency.” Bill and Hillary were met with enthusiastic crowds at each stop, and his imminent arrival helped push the peace process forward.

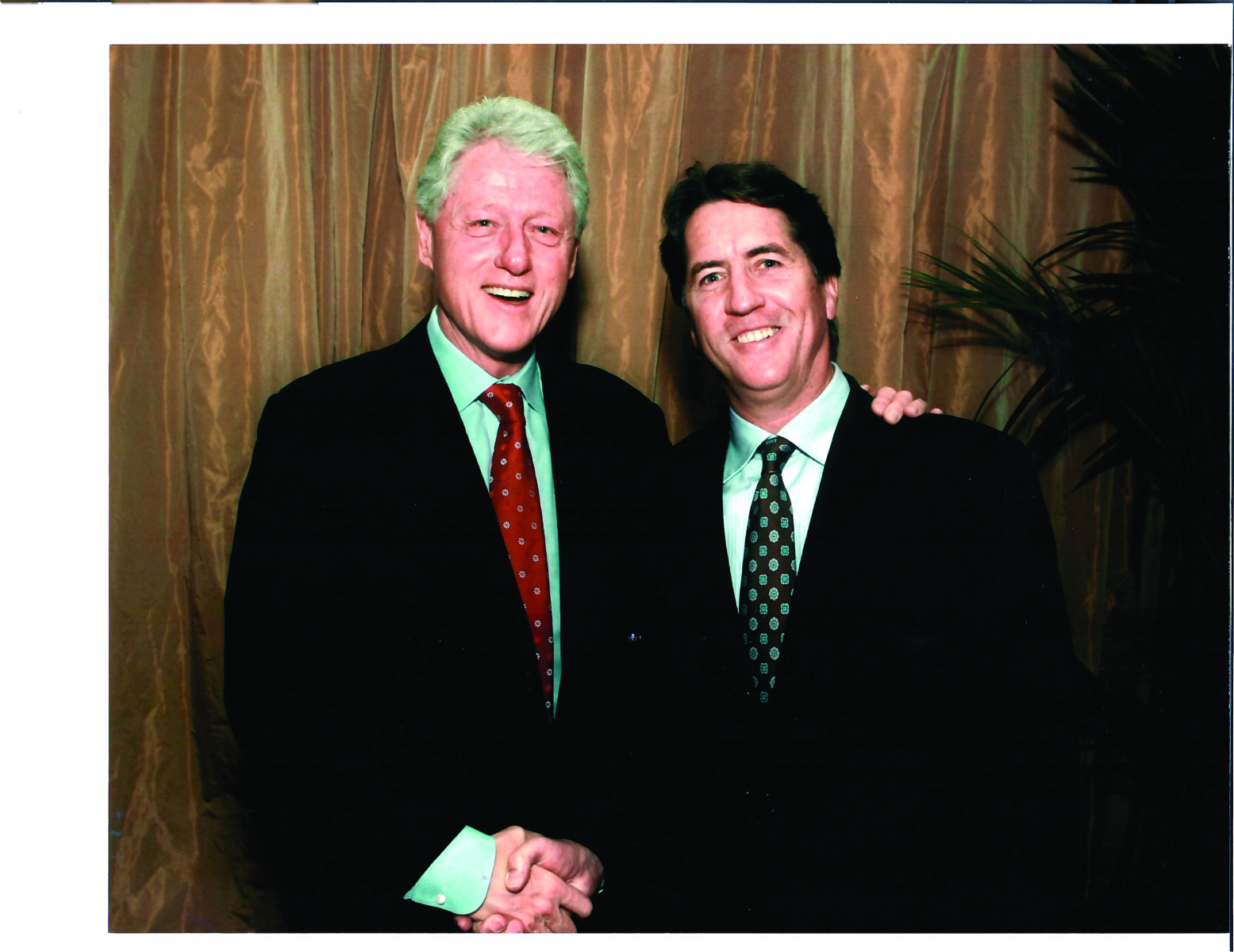

After he left the presidency, I had the opportunity to speak with Clinton a number of times about Northern Ireland. Whenever I brought up the subject – in one instance about a talk he gave in Dundalk in December 2000 – his face lit up. He told the Dundalk crowd that night that “money isn’t everything, but it’s up there with oxygen,” a reference to the economic dividend that peace had encouraged. I suggested to Clinton that I saw him as a “spiritual materialist,” attuned to how economic growth and self-interest can help sustain political institutions but also aware of the ineffable changes necessary for true reconciliation. He seemed to like that description.

Framed on my wall at home is the front page of the Derry Journal for December 1, 1995, the day after Clinton spoke at Guildhall Square. I was at the back of the square when Clinton quoted Seamus Heaney and told the crowd “reach for peace and the United States will reach with you.” Looking up at thousands of people who stood atop the ancient walls, I thought about all of the violence that had occurred nearby. It’s clear from the picture in the Derry Journal article that it was young people who arrived early to stand at the front of the crowd. They are smiling and waving small American flags, delighted at the chance to see what history being made looks like.

Kelly Candaele pictured with students from California State University, Chico, who he brought to Northern Ireland in 2005 to make a film about the peace process. They spent an afternoon with Nobel Peace Prize winner John Hume.

I attended a talk that Seamus Heaney gave at Queens University, Belfast in 1995. He spoke about how the stirrings of peace changed the “discourse” in Northern Ireland. He noted that the shift in political language was akin to a good poem, with “open-ended suggestiveness” that might provide an escape hatch from “binary thinking.”

I still have my copy of the peace agreement that voters, north and south, ultimately approved. The cover is a picture of a family shot in silhouette, walking toward what must be a rising sun. My favorite line in the agreement is the much commented upon section stating that it is the birthright of the people of Northern Ireland to identify themselves as “Irish or British, or both, as they may so choose…” a poetic opening to personal and communal experimentation.

It’s easy, especially for an American, to make too much of the idiom of fluid identities and hope that the agreement would inspire similar efforts in other areas of long-standing violence.

In 2002 I spoke at Hebrew University in Jerusalem about the Good Friday Agreement and its “lessons” for peace in the Middle East. A bomb blast at the Café Moment killed 11 Israeli civilians the day I arrived, part of a surge of violence of the “second intifada.” At the end of my forty-minute lecture, one of the students in the class asked me the entirely predictable question: “What should we do here to achieve what has taken place in Northern Ireland?” My honest but lame answer was that I didn’t know. None of the students or faculty in the room seemed interested in false optimism.

Nevertheless, twenty-five years later, I still regard what I learned in Northern Ireland and the peace that was secured there as highlights of my life.

In his book Ulysses and Us, Declan Kiberd insists that “Ulysses was designed to produce readers capable of reading Ulysses,” and that Joyce, via Leopold Bloom’s meanderings through Dublin, was honoring the quotidian lives of ordinary people. The everyday and familiar “might astonish” and help build a more democratic society, Kiberd writes.

I feel the same way about the Good Friday Agreement. It was created out of a desire to produce citizens capable of embracing its principles of reconciliation. The agreement also reminds us that politics is a primary means by which we structure our relations with one another.

One way of looking at how the Good Friday Agreement happened is to see it as the product of the tireless efforts of “great men” who took “risks for peace” – Hume, Clinton, Blair, Adams, Trimble. From another perspective, it was ordinary people who pushed their leaders forward. Ninety-five percent of the people who voted in the Republic of Ireland and 71 percent of voters in Northern Ireland voted Yes to the agreement. They crossed a psychological and political border that will not be uncrossed.

What a great insight, Kelly. Long before we met in the mid 1970s at Chico State I “met” The Troubles. In August 1969, I got off a Ferry in Belfast from Scotland and was immediately confronted at intersections with concertina wire and I thought I was back in Vietnam. I walked around cautiously. I still remember the night we were near 10 Downing St. and a meeting ended and you observed a Sinn Fein woman go into one of the Red Booth Public phones nearby (was it tapped?) and call Gerry Adams to give him a Report of the meeting. You have been involved in this critical issue for decades and have made a big contribution.