The year was 1981, and Irish American elected officials – including the junior U.S. Senator from Delaware, Joe Biden – had plenty of reasons to be concerned.

Yes, another festive St. Patrick’s Day in Washington D.C., was approaching.

But so were some of the darkest days of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

Amidst rising clashes on the streets of Belfast, an Irish Republican Army (IRA) incarcerated leader named Bobby Sands had just initiated a Hunger Strike in County Down’s notorious Maze prison.

This came not long after the IRA assassination of Lord Louis Mountbatten in Sligo, which brought the 1970s to a violent end in Ireland.

Queen Elizabeth’s cousin was killed – not coincidentally – just months after the election of a new British prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, who vowed to shake up the status quo.

“Then history pivoted,” Rory Carroll writes in his new book There Will Be Fire: Margaret Thatcher, the IRA and Two Minutes that Changed History.

New “Friends”

Two weeks into the Maze hunger strike, a Northern Irish seat in Britain’s parliament opened up.

Nationalist leader Gerry Adams suggested “running Bobby Sands in the by-election as a candidate for Sinn Féin,” Carroll writes.

Volatile forces in the North were about to converge – the ballot and the bullet, martyrdom and pragmatism, the past and the present.

Into this fray leaped a new U.S. group called “The Friends of Ireland” (FOI).

“It will strive to inform Congress and the country fully about all aspects of the conflict in Northern Ireland,” a group statement said on St. Patrick’s Day 1981, “to serve the cause of peace and to facilitate greater understanding of the positive role America can play.”

The most prominent “friends” were the so-called “four horsemen” of Irish American politics – New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Governor Hugh Carey, Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy, and Congressman Tip O’Neill.

Irish American elected representatives – from future president Joe Biden to Maine Senator George Mitchell to Boston Congressman Richie Neal – were also active in the group. They hoped their influence would help bring lasting peace to the land of their ancestors.

“We look to a future St. Patrick’ s Day … when true peace shall finally come and Irish men and women everywhere – from Dublin to Derry, Boston to New York, and Chicago to San Francisco – shall hail peace and welcome the dawn of a new Ireland,” FOI declared in 1981.

The group was a “new forum for the responsible discussion of what Americans can and should do to help,” a March 1981 New York Times editorial declared. “Joining (FOI’s) appeal are 20 prominent Americans, Democrats, and Republicans, Catholics, and non-Catholics.”

The Times added that some saw FOI as “an open challenge to the Ad Hoc Congressional Committee for Irish Affairs, led by the clamorous Mario Biaggi of New York,” who – according to the paper of record – “has yet to find words to disavow the bomb and bullet.”

FOI could “counter the confusion about who speaks for the United States, and in doing so make common cause with advocates of peace and reason in Britain and Ireland … American pressure for moderation can help contain the politics of hate,” the Times article ran, ending with the words, “May the Friends of Ireland provide it.”

With the Good Friday Agreement now 25 years on, many experts agree that FOI helped bring that peace.

U.S.-Ireland Relations

FOI was just the latest development in U.S.-Ireland relations, which stretched back to the ill-fated 1798 rebellion led by Wolfe Tone, through the 19th Century Fenian movement, and into the 20th Century, with the Easter Rising, and Eamon de Valera’s tour of America’s Irish enclaves.

In fact, in 1919, the future president of Ireland gave a rousing speech in Scranton, Pennsylvania, where Jean Finnegan – President Biden’s mother – was growing up in an Irish Catholic family.

Not long after, De Valera led one Irish faction against another in a bloody civil war in 1922-23 over whether or not to accept the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which created an Irish Free State for 26 counties while maintaining the partition of Northern Ireland.

Irish nationalists/republicans continued to seek a united independent Ireland and end discrimination against the Catholic minority in the North. Violence erupted in 1969 when peaceful demonstrators were fired upon by the British Army, sparking the Troubles which would last for 30 years. FOI aimed to end the bloodshed and bring as many players as possible to the negotiating table.

“The Friends of Ireland … play(ed) an influential role in Ulster politics,” Belfast native and historian Andrew J. Wilson has written. It became “an integral factor” in the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985, “which gave the Irish government an advisory role in Northern Ireland,” Rory Carroll writes.

Dark Times

It’s easy to forget just how dark a time the 1980s were – in Ulster, as well as Irish American enclaves.

Over 2,000 deaths were attributed to the Troubles in the 1970s, and the fierce debates over the Hunger Strikes, and status of Republican prisoners, suggested things were only going to get worse.

A particularly gruesome moment came in December 1983, when an explosion at a London department store killed eight people, including a businessman from Chicago. Three other Americans were injured in the suspected IRA attack.

Vocal opposition to British policies, and support for Catholic civil rights in the North, had led some to suggest that the vast majority of Irish Americans unconditionally supported violence.

The U.S. federal government targeted nationalist groups like NORAID (Irish Northern Aid), just as several Irish Republicans were detained for using forged documents to cross the Canadian border, to organize “clandestine fundraising and weapons procurement ventures,” as Andrew J. Wilson puts it.

Most infamously, notorious South Boston gangster Whitey Bulger organized a shipment of arms to Ireland, one of many dark tales Long Island native and former U.S. Marine John Crawley told in his recent book The Yank: The True Story of a Former U.S. Marine in the Irish Republican Army.

Dialogue & Compromise

Amidst all of this, it was easy to forget how many Irish Americans were making more constructive contributions to what came to be called the peace process.

Cork native and New York City police officer Denis Mulcahy had been coordinating Project Children since 1975, bringing often-traumatized boys and girls from Northern Ireland to the U.S., exposing them to new environments and people, in the hopes that they would later help break the North’s cycle of sectarian violence.

Also in the early 1980s, New York Irish American Patrick Doherty was part of a group that proposed guidelines linking U.S. investments in the North to anti-discrimination initiatives.

Irish statesman and human rights activist Sean MacBride – a Nobel Peace Prize-winner and founding member of Amnesty International – lent his name to the effort, and the “principles” that bear his name were born.

FOI also worked in this consensus-building tradition, with an emphasis on dialogue, compromise and healing. FOI delegations visited Belfast, elevating the profiles of lesser-known figures such as the Social Democratic Labor Party’s John Hume.

Violence continued to cast a terrible shadow over Ireland and England, most vividly in October of 1984, when an IRA bomb nearly killed Margaret Thatcher. And yet, just a year later, the British prime minister “signed the Anglo-Irish agreement with Ireland’s prime minister, Garret Fitzgerald. The landmark treaty gave the Irish government an advisory role in Northern Ireland,” Rory Carroll writes.

“The treaty did not end the Troubles, but it did transform British-Irish relations and laid a foundation for a future peace settlement.” And so, as the 1990s dawned, the Friends of Ireland, and others, built on this progress to initiate a new series of historic developments that would culminate in the Good Friday Agreement.

(Arguably, the MacBride Principles would become more influential in achieving change in this area than the Anglo-Irish Agreement. The U.S. House and Senate passed the MacBride Principles – as part of the Omnibus Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 1999 – and President Clinton signed them into law.)

The 1990s

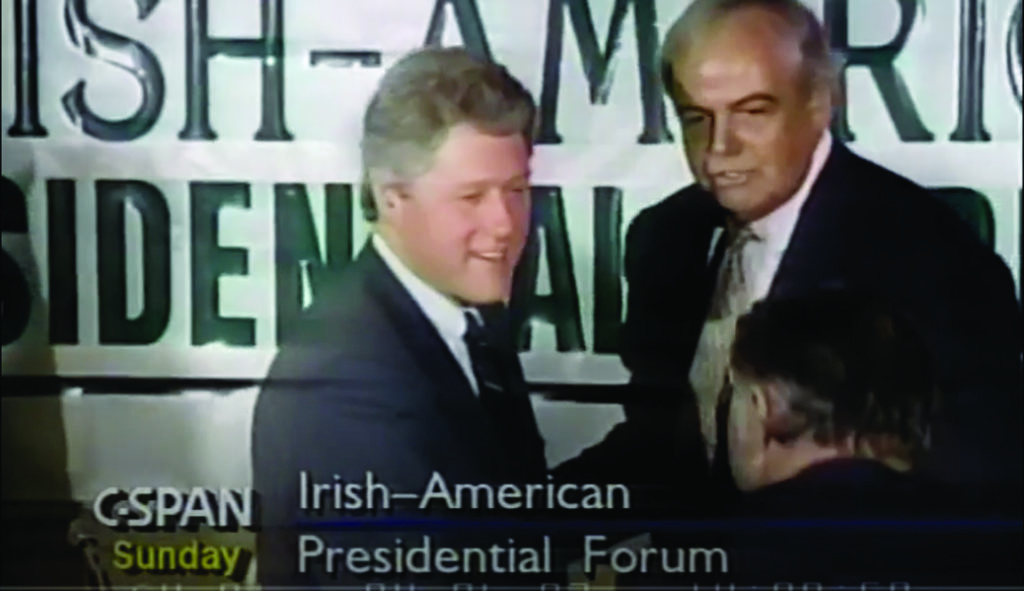

The election of President Bill Clinton was a critical turning point in Northern Irish history. He was still just a candidate when an extraordinary meet up got his attention.

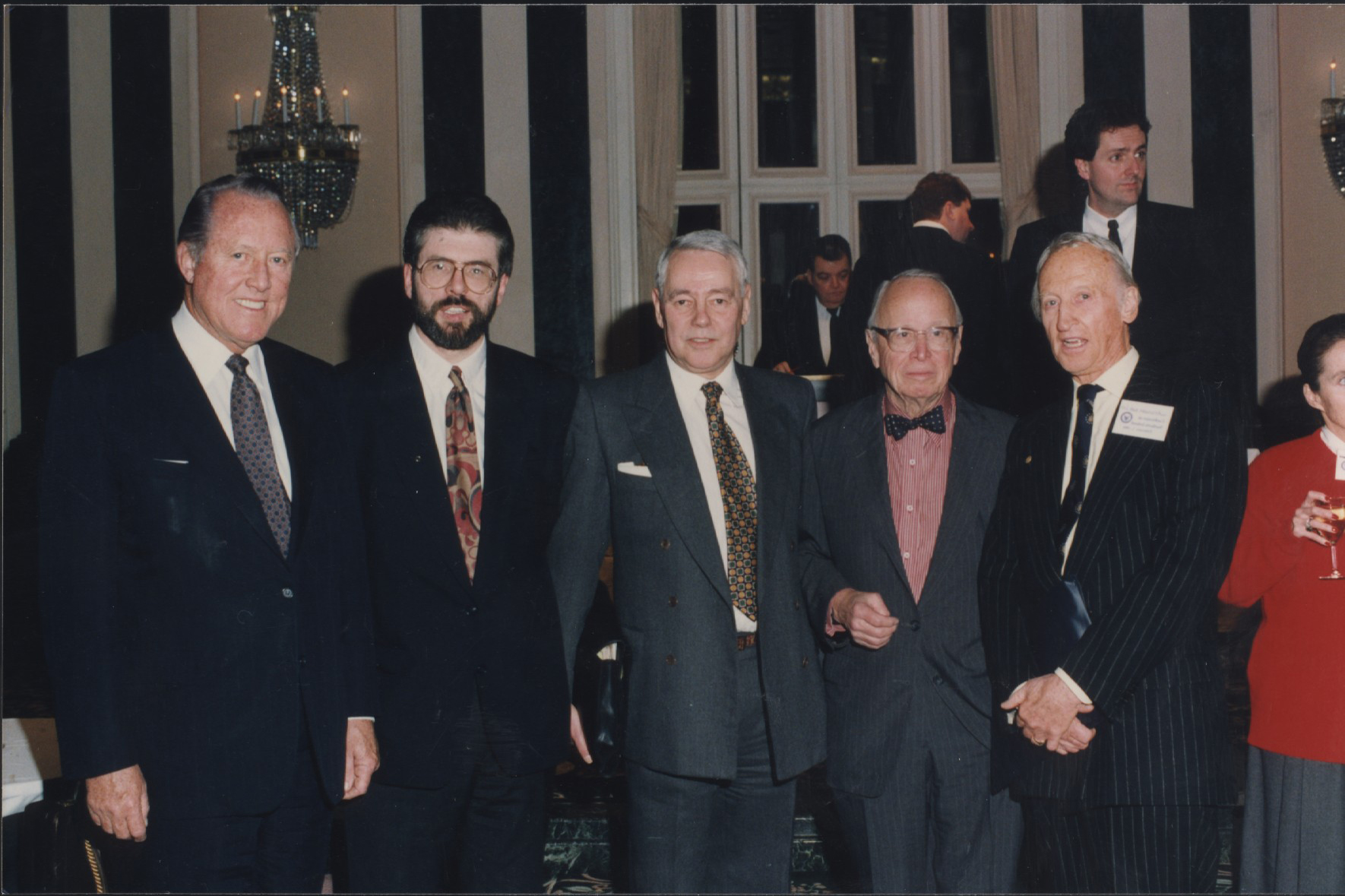

“In April 1992, a well-known Irish American, John Dearie, organized a forum on Irish issues in Manhattan’s Sheraton Hotel for Democratic presidential hopefuls, Bill Clinton and Jerry Brown,” Gerry Adams recalled in his book, A Farther Shore: Ireland’s Long Road to Peace,“Clinton [who arrived and left before Brown] was asked by one of the panelists if [elected] would he appoint a peace envoy for the North. He said he would. When Martin Galvin of NORAID (an American support group for the republican cause) asked the presidential candidate if he would authorize a visa for me and other Sinn Féiners to visit the U.S., Clinton replied, ‘I would support a visa for Gerry Adams.’ Clinton went further and endorsed the MacBride Principles. His responses received loud applause.”

When elected, Clinton carried through on his promises, over the staunch objections of the president’s close advisors, the State Department, and the British government, Gerry Adams was granted a 48-hour visa to visit the U.S. in 1994. [For more on the Adams visa, read Last Word on p. 96].

This was at a time when Adams was such a pariah in certain circles that he was banned from Irish and British broadcasting, which forced news programs in the U.K. to dub the Sinn Féin leader’s voice, so as to keep up with the latest developments from Northern Ireland, while also abiding by regulations. The Adams visa ruffled many feathers on both sides of the Atlantic but it also created more opportunities for discussion and debate of critical issues. FOI and other American participants in the peace process nudged traditional adversaries closer together, even after decades of refusing to compromise. And in many circles, the Adams’ visa was seen as a catalyst to the IRA ceasefire on August 31 1994.

President Clinton’s visit to Northern Ireland, further encouraged the peace process.

“Have the patience to work for a just and lasting peace,” Clinton told a large crowd in Derry’s Guildhall Square late in 1995 on his first trip to Ireland.

“Your great Nobel Prize-winning poet, Seamus Heaney, wrote the following words … that for me capture this moment. He said: ‘History says, don’t hope on this side of the grave, but then, once in a lifetime, the longed-for tidal wave of justice can rise up. And hope and history rhyme. So hope for a great sea change on the far side of revenge. Believe that a further shore is reachable from here. Believe in miracles and cures and healing wells.’”

He ended his speech with the words: “And so I ask you to build on the opportunity you have before you; to believe that the future can be better than the past; to work together because you have so much more to gain by working together than by drifting apart. Have the patience to work for a just and lasting peace. Reach for it. The United States will reach with you. The further shore of that peace is within your reach.”

When Clinton named FOI founding member George Mitchell Special Envoy to Northern Ireland, it seemed a once-in-a-lifetime moment when – to paraphrase Seamus Heaney – hope and history just might rhyme.

On April 10, 1998, British and Irish officials signed the Good Friday Agreement, which was later overwhelmingly approved by voters in Ireland’s north and south.

The gruesome Omagh bombing four months later, which killed 29 people, threatened to send Northern Ireland back into a cycle of violence.

But the fragile peace held, in no small part thanks to the dedication of FOI’s George Mitchell, to whom Bill Clinton awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom on St. Patrick’s Day in 1999.

“Through more than 100 trips across the Atlantic, [Mitchell] continued to press ahead in the cause of peace,” Clinton noted at the time, adding: “I will say what I have said from the beginning: The United States will support all sides in Ireland that take honest steps for peace.” And it has.

Brexit & Beyond

A new century has brought new challenges to the Friends of Ireland.

In 2019, FOI Co-Chair Richie Neal was joined by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Pennsylvania Congressman Brendan Boyle on a trip to Northern Ireland amidst a broader debate over Great Britain leaving the European Union. The process known as Brexit became an unexpected bump in Northern Ireland’s road to a just and lasting peace.

Members of the FOI delegation crossed the Irish border at Bridgend, Donegal, as part of a broader effort to make sure that Brexit did not upend the North’s tenuous peace.

“Tension over the status of Northern Ireland has bedeviled negotiators since Britain voted in 2016 to withdraw from the (European) bloc,” the New York Times has noted.

Brexit exposed a wide range of complications related to borders, trade and enforcement, since Ireland remained in the E.U., while the North would be leaving, along with the rest of the U.K.

Fears grew that “hard borders” would bring back hard feelings on all sides. Once again, Ireland’s friends in the U.S. got involved.

“It played a role, the U.S.,” Ambassador of the European Union to the U.K. João Vale de Almeida recently said, of the Brexit resolution.

“I think it was important that the U.S. was very clear that this situation should have no impact on the Good Friday Agreement and that we needed to find a solution.”

A New York Times report added: “President Biden, who values his Irish heritage, had made it clear that a negotiated solution was needed if there were to be a presidential visit to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement.”

And so, despite two-and-a-half decades of challenges, Biden and the Friends of Ireland have helped change the course of Irish history.

“I’m proud to say that the bond between Ireland and the United States has grown deeper and stronger over the years,” Biden said at last year’s annual FOI St. Patrick’s Day meeting.

“We’ve navigated a once-in-a-century pandemic together. We’ve grieved the loss of too many people in both our countries. And we worked to rebuild our economies and taken on the challenge of renewing and strengthening our democracy. I think we’re at an inflection point in history… we’re in a genuine struggle between autocracies and democracies, and whether or not democracies can be sustained.”

Clearly, there are still many challenges to face. For now, though, hope and history continue to rhyme.

Leave a Reply