Sean Granahan is determined to keep The Floating Hospital afloat

It’s been nearly 20 years since Sean Granahan found himself in a diner on the West Side of Manhattan, staring at a piece of paper. “The numbers weren’t pretty,” Granahan recalls. “In fact, they were un-pretty.”

A lawyer, Granahan had spent the previous several years doing work on behalf of a New York-based charity called The Floating Hospital (TFH). By the early 2000s, TFH had…well, sailed into choppy waters.

“So I went to this meeting with four of the board members,” Granahan recalled. “And was handed a letter by the then-Executive Director (of TFH), who was resigning. In his letter, he just said it would probably make more sense to close it.”

This would have been an unceremonious end for a celebrated charitable organization that had been helping New York’s tired, poor, huddled masses since the dark years that followed Ireland’s Great Hunger.

Something Different

Granahan himself grew up in the Irish stronghold of Scranton, Pennsylvania, best known these days as the birthplace of Catherine Eugenia Finnegan’s ambitious son – President Joe Biden.

By 2004, Granahan had spent well over a decade as a business lawyer working on high-profile cases, including intricate insurance claims resulting from the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center.

“After spending two years in a conference room, with literally tens of thousands of printed emails laid out on a table…preparing for trial,” Granahan said, “I was ready to do something different.”

During that Manhattan diner meeting with TFH board members, things did not look promising. But by then, Granahan had gotten to know TFH’s staff and volunteers.

“It’s hard to work there and not be affected by the dedication of the staff. You’d have to be a mummy not to be affected by them.”

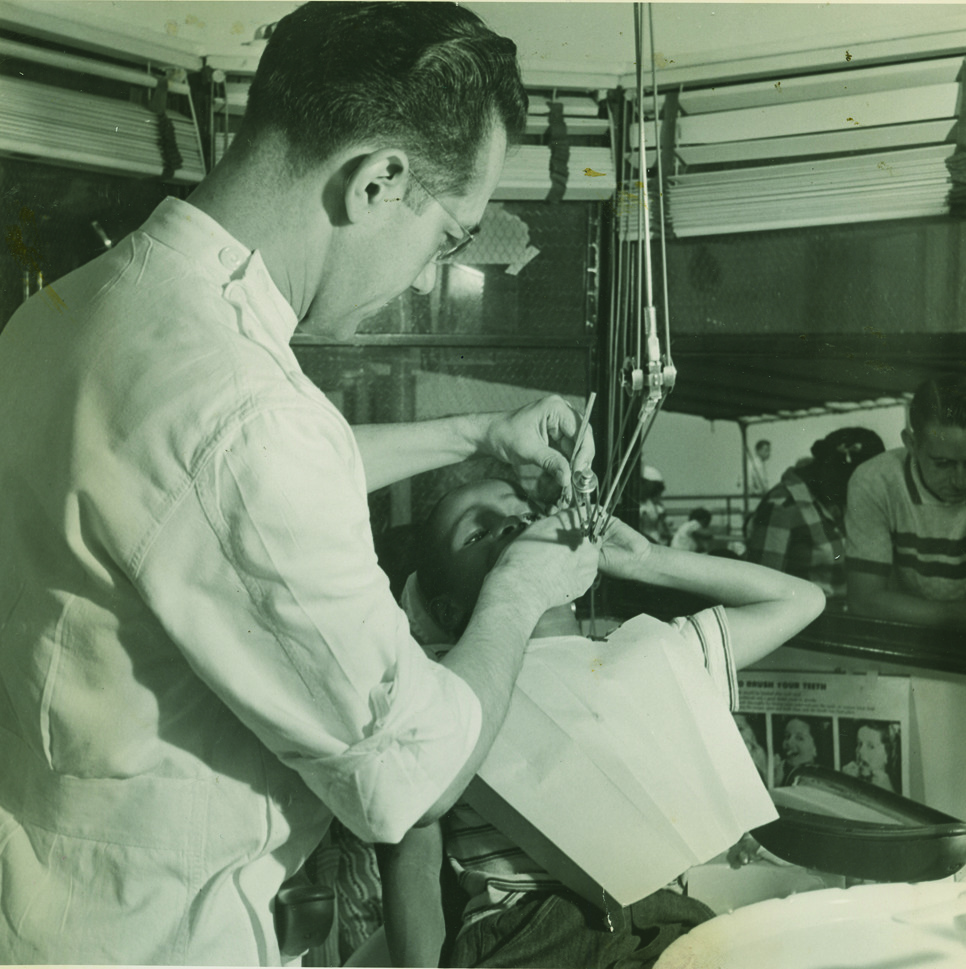

Then there were the parents and children who utilized TFH’s wide range of services – from medical and dental care to financial literacy and emotional support. Day in and day out, Granahan said, he saw TFH staff meet these complex needs with generosity and kindness.

“That’s something, as a regulatory lawyer, you don’t see every day.”

And so, at the end of his 2004 meeting with TFH’s board, Granahan proposed a series of potential solutions to keep the charity up and running.

“I said give me six months,” Granahan recalled. “And here we are, 20 years later.”

Daily Health Hazards

The history of New York City – and maybe even of immigration in America – could be told through the history of The Floating Hospital.

It rose from New York’s cobblestoned streets after the devastation and division of the U.S. Civil War, and the 1863 Draft Riots that turned swaths of Manhattan into rubble.

Back then, daily life was a health hazard – coal smoke, poor plumbing, horse manure, and the insects it attracted. All of this contributed to pervasive illness and disease – malaria, dysentery, asthma, cholera, and tuberculosis, the latter of which was referred to by some as “the natural death of the Irish.”

These were the people who survived the “coffin ships.” Yes, Tammany Hall’s efforts to organize these immigrants might include food or shelter. And Irish-born New York Archbishop “Dagger” John Hughes had started building a Catholic social services network of schools and hospitals.

Still, demand for help was far greater than supply. And it didn’t take long for native-born Protestants to grow sick and tired of these needy, numerous foreigners.

Celebrated American artist Thomas Nast – so fondly remembered for his festive holiday images of Santa Claus – churned out dozens of anti-Irish cartoons for popular publications. “The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things,” for example, featured an ape-like Irishman, swinging a bottle of rum in one hand and a flaming torch in the other, while seated atop a barrel of gunpowder.

Charles Loring Brace, the founder of the Children’s Aid Society, wrote his popular book The Dangerous Classes at this time, outlining the menace posed by “the ignorant, destitute, untrained, and abandoned youth: the outcast street-children grown up to be voters, to be the implements of demagogues, the ‘feeders’ of the criminals, and the sources of domestic outbreaks and violations of law.”

It was in this atmosphere that The Floating Hospital began its work, in 1866.

Healthy Air

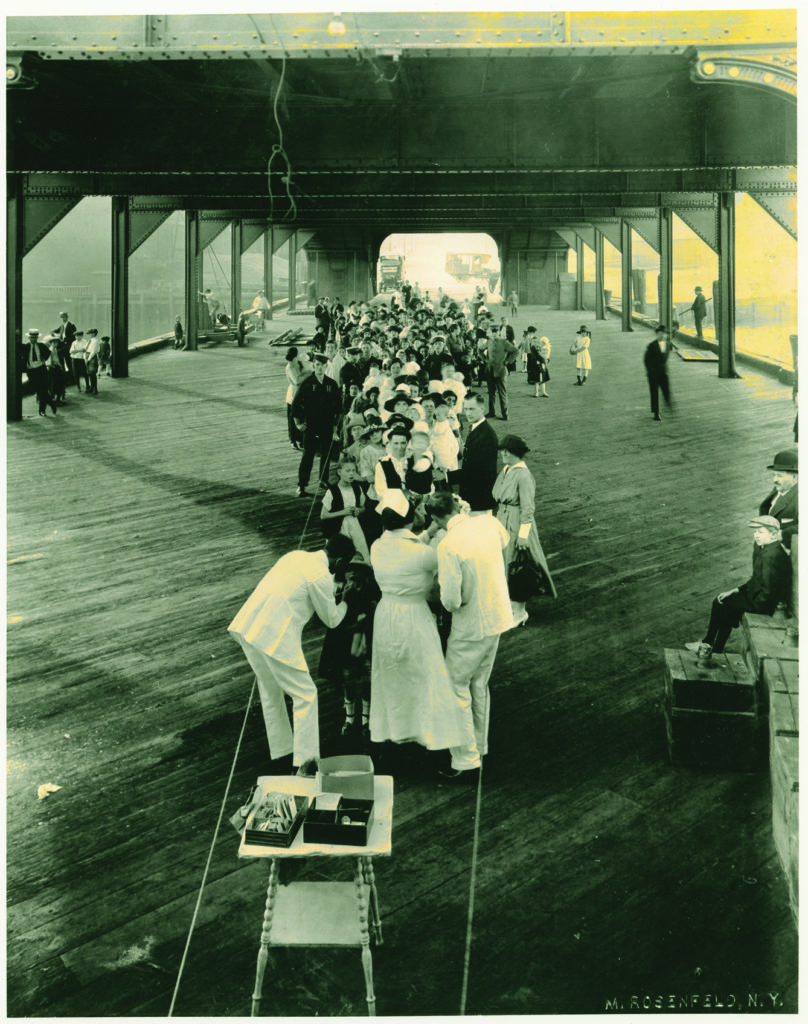

Several years later, a Trinity Church relief organization called St. John’s Guild organized boat rides up and down New York’s East and Hudson Rivers. Well over 20,000 impoverished New Yorkers a year took advantage of the boat excursions, according to TFH.

“The idea of a floating hospital arose out of disease management,” Granahan notes.

“At the time, the thinking was that sea air helps keep the lungs functioning better… . The easiest way to deal with (airborne diseases) was to put people on a barge and get them away into the fresh air for a little while.”

Over the next century, the St. John’s Guild Floating Hospital launched a number of ships named for famous patrons, from opera singer Emma Abbott to publisher and philanthropist Lila Acheson Wallace.

And through the Gilded Age and the opening of Ellis Island, the gangster crime waves of Prohibition, and The Great Depression, TFH has maintained the same mission it does today: “Unrestricted compassionate and high-quality healthcare to all who walk through our door, regardless of insurance status, immigration status, or ability to pay.”

For decades, Granahan says, the mere novelty of helping New Yorkers while on a boat attracted those who might not otherwise have sought help.

TFH has since shifted entirely to “land-based” services – though one of Granahan’s top priorities is to get the group back out on the water.

“We’ve got this unbelievably rich maritime history,” he says. “It’s a rare thing in the healthcare field.”

Either way, parents who visit the various TFH sites throughout New York City – often after a ride in one of the group’s “Good Health Shuttle” vans – say the array of services has helped simplify the very complicated, very important process of healthy living.

“I don’t have to take public transportation,” said one mother who is living in a shelter with three kids. “It’s a lot to take all three kids on the train.”

Adds TFH Executive Vice President of Clinical Administration and Chief Medical Officer Shani Andre: “We were founded as a charity hospital and we still have that same mission. We want to be that doctor that’s the one-stop-shop that everyone in your family can see.”

Challenging Times

Though TFH has a history of overcoming great odds, Granahan admits: “We’re facing extremely challenging times right now…probably right up there with the days of the great waves of immigration from the early 20th Century.”

In recent years many distinct social problems have collided to create a perfect storm.

The opioid addiction crisis, for example, has changed the nature of substance abuse, a longtime source of struggle for many Americans.

So, even before the ravages of the 2020 pandemic, American poverty was a crippling problem, experts say.

“On the eve of the Covid pandemic, in 2019, our child poverty rate was roughly double that of several peer nations, including Canada, South Korea, and Germany,” Matthew Desmond wrote recently in The New York Times. Desmond won a Pulitzer Prize for an influential book about America’s housing crisis. His new book, Poverty, by America shines a harsh light on many of the issues Granahan and TFH contend with. “Anyone who has visited these (other) countries can see the difference, can experience what it might be like to live in a country without widespread public decay,” Desmond continues. “When abroad, I have on several occasions heard Europeans use the phrase ‘American-style deprivation.’”

As the illness and unemployment of the pandemic finally fade, its long-term impact has created a broader array of interconnected social problems: upticks in crime, high inflation, and the ever-spiraling cost of housing in New York and other cities.

Thousands of families are drifting into homelessness or getting by in substandard housing, even as “just a few blocks away,” Granahan adds, “there’s a row of multi-million dollar homes.”

All this means is that TFH and its staff are trying to stave off what Granahan calls “a humanitarian crisis.”

Migrant Arrivals

Then there are the 50,000 migrants who have moved from the southern border to New York City in recent months. Such a challenge has special resonance for Granahan, given his family’s connection to the Irish immigrant experience.

“That’s something that’s always there in the back of your mind,” he says. “(Immigrants) are always part of who we are.”

The result, according to TFH, is that one out of every 100 infants currently born in the five boroughs of New York City is homeless.

This only exacerbates an array of related challenges, from substance abuse to domestic violence and hunger to illness.

“The most difficult thing about this work is knowing that you can’t help everyone as much as you want to,” Granahan says. “You worry about the kids who don’t make it to The Floating Hospital. That’s who you worry about.”

This is why it’s important to stop and appreciate the words of those that TFH does reach.

“I was living in a shelter in Brooklyn with my daughter. We were undocumented,” a TFH client recently said, outlining just the beginning of her problems.

“I was also a cancer patient. Being stranded, sick, and helpless, with no food, no benefits. Nobody wants to be homeless.”

Amidst all this, she says TFH was “my savior. During my instances of domestic abuse, I could come here.”

Another mother said TFH “makes me feel like I’m supermom. Because I’m doing what I have to do for my child.”

What clients see as miracles, though, is just another day at the office for Granahan.

“Every day a dozen vans go out to homeless shelters and bring (people) to us…. We roll up our sleeves and make it work.”

From Ireland to Scranton

Granahan’s personal journey to this work began in northeastern Pennsylvania.

“I loved growing up (in Scranton),” recalled Granahan. “There’s a lot of Irish there… . It’s part of the culture growing up.”

Granahan attended local Catholic schools, before moving on to the University of Scranton, a Jesuit college.

Granahan’s father remains a longtime member of the Lackawanna County Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, one of the largest such groups in the U.S.

“(Being Irish) has always been extremely important to my Dad,” Granahan says, adding that he’s in the process of obtaining Irish citizenship for his father, who has taken many trips to Crossmolina, Mayo, and elsewhere in Ireland.

“He reconnected with members of the family…He really brought the culture home.”

Granahan’s father also had quite a powerful influence on his career.

“My father really made the decision for me to go to law school,” he recalls with a laugh.

After passing the bar, Granahan clerked for Federal Judge William J. Nealon, his mentor, before spending several years as a lawyer in the long-haul trucking and warehousing world. He then moved on to the New York City area, to work for the Park Avenue law firm of Epstein, Becker, and Green, whose clients ranged far and wide, from Fortune 500 companies to hospitals.

“As a lawyer, it’s good to have a bunch of different experiences, so you can give the best advice. It’s not just the knowledge of the law but also the circumstances surrounding the law.”

In the wake of the horrific September 11 attacks, Granahan was assigned to work on complex real estate and insurance cases related to the destroyed Twin Towers.

Little did he know, at the same time, in the same part of New York City, another historical chapter was drawing to a close.

The actual Floating Hospital boat took part in rescue efforts on 9/11. In the sad, hectic weeks that followed, the vessel ended up losing its docking space. The ship was ultimately sold off, and the buyer proceeded to let the ship to fall into disrepair – the state in which it currently remains, docked and rotting in the northern reaches of the Hudson River.

Granahan says that ship can’t be repaired – though a key TFH long-term goal is to get the organization back on the water through refurbishing an affordable barge.

It’s a personal, as well as professional goal.

“I know very few Irishmen who don’t love the sea.”

“Rise Up”

Until then, Granahan and TFH have plenty of other challenges to tend to.

Consider the sprawling New York City public school system, where over 100,000 students live in temporary housing. TFH works to reach this population through a program called Camp Rise Up, an upstate New York getaway for a population that is at “higher risk for teen pregnancy, using drugs and alcohol, being in unhealthy relationships,” according to camp director Meghan Miller.

“We like to have Camp Rise Up as kind of a crash course in all of these really important topics.”

Aside from this social-emotional education, participants swim, hike, canoe, and even take flight by zip-lining.

“I’m afraid of heights,” one participant said. “I’m glad they pushed me out of my comfort zone.”

Some TFH staff have seen Camp Rise Up kids return for up to five years, watching them grow and mature before their eyes. Many of the campers become counselors themselves, and TFH helps them transition into jobs as part of the curriculum.

Experiences like this compel Granahan to say that for all of the challenges facing TFH, there are plenty of reasons to be optimistic about the future.

“That’s what I love about New York City. You turn the corner and something good happens. If you believe in things like karma, good things have happened to us. We have an important story to tell. And we go out there and do it…. It’s tough. But we’ll continue to help families who need the help.” ♦

Editor’s Note: The Floating Hospital hosted its annual Summer gala on Monday, June 12, 2023, at The Metropolitan Club. The theme was the 1920s and the crowd embraced the spirit of the evening.

The support received from guests and sponsors allows The Floating Hospital to continue the vital work that they do which is so much “more than healthcare.”

In addition to healthcare, The Floating Hospital provides 25,000 children with the essentials that they need every day including clothing, food, personal healthcare products, baby necessities, children’s toys, books, and transportation.

To learn more about The Floating Hospital and the vital programs they provide visit their website.

Leave a Reply