Senator George Mitchell turned out to be the star of the Agreement 25 conference held April 17-19, 2023 in Belfast at Queens University to mark the twenty-five-year anniversary of the signing of the Good Friday Agreement that largely ended the sectarian war that had devastated Northern Ireland. In a keynote address on the first day of the conference he noted that “If history teaches us anything, it is that history itself is never finished,” and that it will take other leaders in the future to safeguard the work of the Good Friday Agreement. Later, a bust of Senator Mitchell was unveiled in front of the conference center where political leaders, diplomats, and community leaders were gathered. Mitchell’s sculptured face was directed towards the entrance to the meeting hall, as if he was saying, “I’m watching to see what progress you can make in the future.”

Mitchell served as President Bill Clinton’s special envoy to the peace talks. It was generally acknowledged that without his steady presence and political skill, the talks likely would have faltered.

Later during the conference, Mitchell, who has recently been ill, spoke to Irish America Magazine and said that he deliberately brought an approach of “fairness, openness and listening to all sides,” in order to move beyond the objections that some members at the all-party talks had to his participation. “Really listening is hard,” Mitchell said, “especially if it’s over a period of years.”

He added that “life is change, for every human being, for every family, for every government, for every society.” “But it’s also a sign of respect. It says to people, I value you, I value your views.”

The conference was divided into three days, each with its own theme: day one – Reflection, day two – Renew, and day three – Reimagine. Queens University Chancellor Hillary Clinton presided over the conference. She opened up the proceedings and praised the “tough, determined, everyday people,” of Northern Ireland who decided to move forward away from violence and take risks for peace.

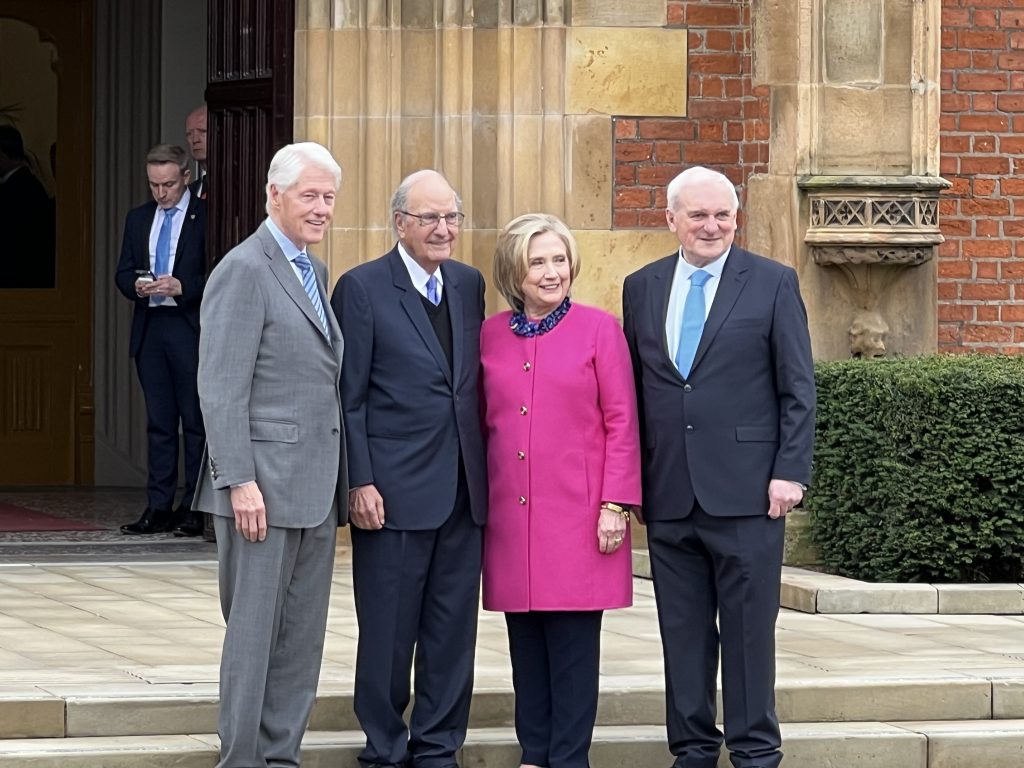

Former President Bill Clinton was also in attendance as well as former Prime Minister Tony Blair and former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern, all of whom played key roles in securing the peace deal. On the final day of the conference, Clinton honored the memory of Nationalist John Hume and Unionist David Trimble, two politicians who won the Nobel Peace Prize for their work. “Both knew they would suffer politically for their success,” Clinton pointed out. He added that if alive today, despite the political decline of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) both Hume and Trimble would have said “I’m glad we did that.”

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and Taoiseach Bertie Ahern

Most of the conference was rightly focused on the future. “I try to live in the present and for the future and so should we all,” Clinton suggested. Two hundred students from Belfast attended a conference session on the future of politics and community relations in Northern Ireland. Niamh Lowe, a 21-year-old student at Queens spoke about the impact of the Good Friday Agreement. “It made a massive difference,” she said. “Queens is quite mixed now and you wouldn’t even know it because people just work together without even thinking about it.” She added that her father, who grew up on an interface between Catholics and Protestants would probably not be alive today but for the peace agreement.

At the Malone Integrated College, a high school with students from various religious backgrounds and countries, a small group met with American University students from California and New York. Although only about seven percent of students in Northern Ireland attend integrated schools, all of those at Malone felt that mixed education was one of the ways that Northern Ireland could move forward.

Malone student Nathan Buttimer heard tales from his parents about bombs going off and being searched before going into stores in the Belfast city center. “I get told how lucky we are,” he said. “I can’t see myself living like that and I don’t think anyone else in this room can either.” Ashlyn Hodgen from Sandy Row, a Loyalist enclave a block away from the Europa Hotel in downtown Belfast, spoke of her desire to use the peace provided by the Good Friday Agreement to expand her group of friends and her future opportunities. “Even though I grew up in a Protestant community I have friends from different religions or no religion. We are essentially all the same,” she said.

Even though there is peace, the “peace walls” that separate the Catholic Falls Road from the Protestant Shankill are still in place, a dreary reminder that for all the talk of progress at the Queens conference, hardened structures and attitudes forged during the decades of conflict have not disappeared. The Northern Ireland Assembly has been collapsed for over a year, and the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), now the largest Unionist party in Northern Ireland, has wagered that intransigence rather than compromise is more beneficial for them politically.

Touring Bombay Street, a Catholic area along the Falls Road, trade union leader Brian Campfield remembered the night Bombay Street was burned down by a Loyalist mob. “It was really out of youthful curiosity that some friends of mine and I were here in 1969,” Campfield recalled. “Because local people had to fend for themselves because there was no police protection it gave a big impetus to forming and strengthening the Provisional IRA.”

Wire cages to protect from thrown bottles or bricks are still in place covering the backyards of homes that are built up against the wall that separates the two communities.

At one of the several panels at the conference, former Sinn Fein President Gerry Adams made a case for “gentle persuasion” of the Unionist community and flexibility on how to proceed forward. “On an island this size with a population this size it doesn’t suit to face away from each other,” Adams said.

President Biden had visited Belfast for a day during the week prior to the conference. Some commentators felt that he presented a “misty-eyed” view of Ireland while others saw his somewhat nostalgic view of Ireland as harmless or even endearing.

During his speech at the conference Clinton recognized that there were many people in Northern Ireland who wanted him to “get out of town,” pointing out that his presence was an occasion for those opposed to the peace process to create resentment against him coming in the first place back in 1995. “I think coming in the first place helped you get to where you are now,” Clinton said.

Senator Mitchell turned philosophical during his talk. “All human beings and institutions are fallible,” he said. “But we must continue to wrestle with doubts, differences, and disagreements and that is only natural.” Mitchell spent three years of his life in Northern Ireland doing just that. He returned to Belfast with a sense of pride and accomplishment. “It takes a long time to overcome the scars of conflict,” he said, his voice lowering to an almost whisper. “What is in the human mind and heart is the most important factor of all and it’s the hardest to overcome.” ♦

Read Kelly Candaele’s article Good Friday and Us from the Spring 2023 issue of Irish America.

Jerry Adams said the Good Friday Agreement was possibly the most important agreement of the past century.

“It’s certainly the most important agreement of our time. It’s a rather complex agreement. Interestingly enough, it’s an agreement to a journey without agreement on the destination.”

Amazing how the DUP continues to refuse to re-engage in the power-sharing agreement laid out 25 years ago.

Clearly, the British government needs to more actively engage.