The political process gets underway in Northern Ireland.

12/14/99: A “day unlike any other” was how Taoiseach Bertie Ahern described his feelings at the history-making first meeting of the North-South Ministerial Council in Armagh City on Monday (December 13).

While the media gave massive coverage to the event – it was broadcast live on BBC Northern Ireland Television – the population of the North remained somewhat bemused at the speed of events after 19 months of stalemated negotiations.

In the back of most minds, too, was the lurking fear that all the progress of the last few weeks could be undone if the Ulster Unionist Council – the decision-making parent body of David Trimble’s Ulster Unionist Party – rules in February that the IRA has not made a start to decommissioning its weaponry.

Despite these fears, however, the Irish peace process is due to gather even greater momentum later this week at the inaugural meeting of the British-Irish council and inter-government conference on Friday (December 17) when links will be established with administrations in Dublin, Belfast, London, Edinburgh, Cardiff, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands.

The North-South Council clause, which was inserted into the Good Friday Agreement at the insistence of nationalists and republicans, means that six cross-border bodies will be controlled by committees of ministers from the Northern Ireland Assembly and Dáil Éireann and staffed by civil servants from both sides of the border. The new departments will be responsible for food safety, inland waterways, special European Union programs, trade and business development, language (Irish and Ulster Scots), and aquacultural and marine affairs. Departmental offices will be situated on both sides of the border.

In addition, the joint council will approve arrangements for closer cross-border cooperation on transport, agriculture, education, health, environment and tourism.

Although the North-South Council will sit only twice each year in full plenary sessions, ministers from Dublin and Belfast may meet as often as they feel necessary.

All 15 members of the Irish Cabinet arrived in a cavalcade of limousines which one commentator said was reminiscent of President’s Clinton’s visit to Ireland in September 1998. Ten of the 12 Northern Ireland Assembly ministers were at Armagh District Council offices to greet their southern counterparts. The missing pair, Peter Robinson and Nigel Dodds of the anti-Agreement Democratic Unionist Party, refused to attend, insisting that Irish ministers had no role in Northern Ireland affairs.

Northern Ireland’s first minister, Ulster Unionist leader David Trimble, described it as “the day the Cold War ended” between the six northern counties and the Republic.

Taoiseach Bertie Ahern said: “It is a day unlike any other, when both parts of the island can begin working together in a spirit of friendship and partnership for the mutual benefit of all the people, putting behind them the sectarianism and divisions of the past.”

Developments in recent days, including a report by the head of the international arms decommissioning body, helped ease Ulster Unionists into acceptance of the new council, a form of which they rejected several years ago as “Dublin interference” in the affairs of the North.

General John de Chastelain, who had an unprecedented discussion on arms decommissioning with a senior IRA volunteer recently, described the secret talks as “frank and useful.” The general also confirmed that he plans further talks with the unidentified IRA go-between.

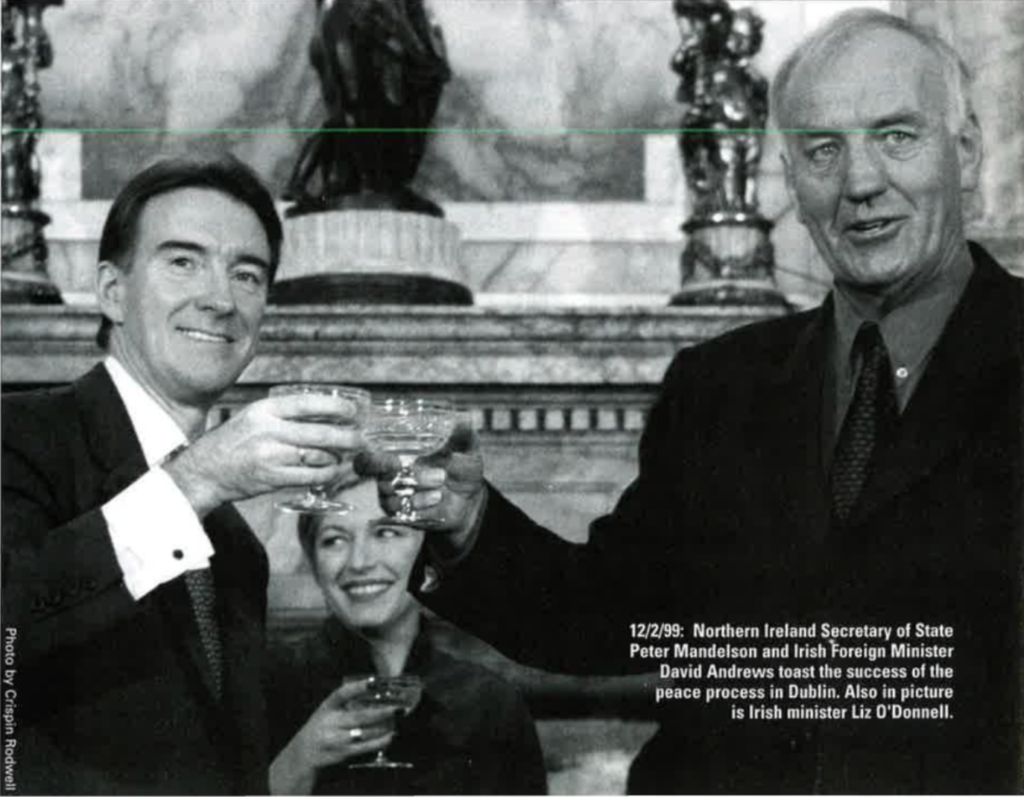

In his low-key report on progress on the arms issue, de Chastelain recommended the setting up of a timetable for decommissioning by all paramilitary groups. The general’s report to Northern Ireland Secretary Peter Mandelson and the Irish justice minister John O’Donaghue was made public within hours of his meeting on Friday with a five-man group representing the loyalist Ulster Freedom Fighters.

The five were appointed last week to act as interlocutors or go-betweens with the commission following the IRA’s agreement to do likewise.

Among the UFF’s go-betweens is Johnny Adair, who was recently released from jail after serving a sentence for directing UFF terrorism. Before his arrest, Adair was a hate figure for north Belfast Catholics who claimed he had been involved in dozens of sectarian murders. The man dubbed “Mad Dog” Adair by the British press was joined in the talks with General de Chastelain by leading loyalists William Dodds, Jackie McDonald and John Gregg. The fifth interlocutor was John White of the Ulster Democratic Party, the political wing of the UFF.

The Ulster Volunteer Force, which appointed their representatives several months ago, has already had meetings with de Chastelain’s commission.

Ulster Unionists claim that progress on the decommissioning issue is crucial to the survival of the new power-sharing executive at Stormont.

First Minister Trimble has threatened to collapse the new administration with his resignation if there is no evidence that the IRA has started decommissioning weapons by February.

Trimble was forced to make his resignation offer in a successful attempt to swing the Ulster Unionist Council behind his bid to form an Executive. The mid-February dateline for the next meeting of the traditionally extreme right-wing council is as much a deadline for Trimble’s leadership as for IRA decommissioning.

Meanwhile, after so many “history-making days” for the North, it was something of a relief for political commentators to be able to report this week that the Assembly had settled down to debating bread-and-butter issues such as its budget and the financial crisis facing pig farmers.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Irish America’s February / March 2000 issue.

Leave a Reply