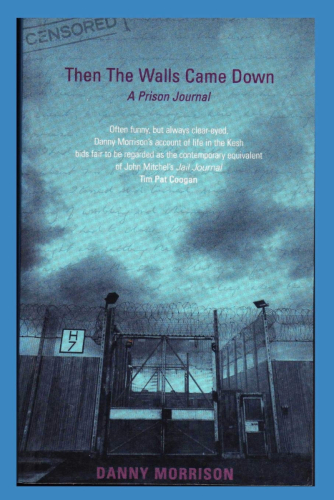

Danny Morrison is listening to a Traveling Wilburys’ tune and remembering a time in bed with his girlfriend Leslie in 1988. The song goes:

And the walls came down.

All the way to hell.

Never saw them when they’re standing.

Never saw them when they fell.

He suddenly sits upright. It is five in the morning, in October 1990, and he is alone in the Crumlin Road Jail, Belfast.

This is one of many entries in Morrison’s prison journal that are uniquely personal and political. The “walls” represent the prison cell in which he dwells, but also the walls separating him from his lover, Leslie. There are also inner walls that serve to shut down his emotions, survival mechanisms that dull life itself. His struggle is to transcend those walls on every level.

The account of his inner journey while a prisoner of the Crown from 1990-1992 is a fine memoir that draws the reader deeply, perhaps unexpectedly, into Morrison’s humanity. Unexpectedly, because Morrison is best known as a political man, Sinn Féin’s publicist during the worst years of the war in the North, who issued the rallying cry for “an armalite in one hand and the ballot box in the other.”

Though “Walls” contains valuable reflections on politics and writing, it is first and foremost a love story. Most of the letters are to Leslie, a Toronto native living alone in West Belfast, and concern for the deep problems of whether love and marriage are sustainable in a time of war.

In 1968, 18-year-old Danny Morrison was waiting tables in a Belfast hotel. He preferred reading Anna Karenina to engaging in politics. But as the Troubles deepened, he writes, “I opposed my own nature and entered into a world of drama filled days.” In November 1972, after just having broken up with his girlfriend, he went to a dance at Clonard Hall on a first date. British troops raided the hall, firing rubber bullets, and arrested some 80 young people suspected of being Fenian subversives. Internment had begun. Morrison was not released until December 1973, when he plunged full time into Sinn Féin activism.

As this 1990s diary begins, it is 18 years later and Morrison is 40, charged with IRA membership, conspiracy to kidnap and murder an informant – who is not only very much alive but a paid witness in the courtroom. Morrison has been married and separated, and is the father of two sons, Kevin (15) and Liam (11). He has fallen in love with Leslie, a Canadian journalist assigned to Belfast. He will ask to marry her “in the right setting when you least expect it…We might be sitting on heather on a warm evening, watching the sun’s golden rays fan out across the heavens when I ask you. Or I might approach you, beginning from the soles of your feet!” But now all he can do on New Year’s Eve is whisper his love through the cell bars, with prison lights blocking the stars. “You make me touch happiness, not just on the border but its capital.”

Morrison the inmate does not fit the common stereotype of republicans as cold, vengeful Catholic fanatics. He reads Flaubert, Shakespeare, Scott Fitzgerald, Milan Kundera, Andre Schwarz-Bart, Malcolm Lowry, Thomas Mann, Vaclav Havel, even Louise Erdrich and Michael Dorris. He studies and rejects Ovid’s advice on women: “Take revenge by silence.” He listens to Schubert’s #5 and studies the composer’s life. He knows the lyrics of Fleetwood Mac.

An independent thinker, he advocates many of the political compromises that Sinn Féin has adopted in the current peace process. One of his prison essays, advocating a shift towards political realism, is rejected by the Sinn Féin newspaper he once edited, on grounds that it would be “seized upon by our opponents.” His 1991 thinking is worth quoting at length:

“The settlement cannot be based on political superiority as a consequence of one’s numbers, but on the basis of equality. A six-county state will always make me feel like the vanquished party. Nor am I so stupid – even if it were possible to achieve a triumphalist outcome – as to want an all-Ireland state from which a quarter of the population felt alienated. We have to find a settlement that takes into account all the contradictory objectives…. Time can exhaust the British. They will end up talking to us, and that’s when our problems will really begin!”

There is plenty of prison humor in Morrison’s memoir, too. Watching a televised soccer match between Cameroon and England, he writes Leslie that “by the way, we’re the Africans.” But the central focus is the crisis that the “walls” impose on his relationship with Leslie, his two sons, and his parents. The heart of the journal is an essay on “Love and Jail,” in which he describes “Just to the side of the struggle, out of sight, lie the corpses of marriage and broken relationships shed by the despairing, who simply couldn’t take it any more…. For someone struggling desperately to hold on to love, no appeal to the happiness of the past or to the promised rosiness of the future can allay for the other person the pain and desolation of the present.”

It is a profoundly political issue, too, because of “the unreality of the way we republicans live — our lives completely and indefinitely subordinated to the pursuit of this struggle.” The draining personal effect is perpetuated by a politics in which personal doubt is a daily threat to iron will.

Morrison’s journal ends in a blow-out with Leslie, who writes on August 14, 1992, that their house had been sold and Danny’s things stored with a mutual friend. The next day Danny writes a rather noble reply, offering support and understanding. On September 3, Leslie weakens her position, proposing that she go stay in Toronto and return when Danny is paroled to “start a new life.” Two days later, a hurt Morrison, feeling a prisoner’s anger that has no control, tells Leslie he can’t take the uncertainty any longer. “Leslie, don’t be coming back for me because I will have moved on.” There the journal ends.

The story beyond the journal has a happy resolution, however. Morrison was released in 1995, and, after another dramatic round, married Leslie and settled down in West Belfast. He remains a strong republican, but considers himself primarily a writer, with three well-received novels: West Belfast (1989), On the Back of the Swallow (1994), and The Wrong Man (1997). His sons carry on his tradition. One of them, Kevin, now 23, was picked up by RUC officers while leaving a disco dance a few years ago and hospitalized for a week from kicks to his groin.

Having known Morrison in the mid-seventies in West Belfast, it is fascinating to see him publicly sorting out the roles of movement activist, independent writer, and human being. “There is less bitterness among the oppressed,” he ventures. It is certainly true of Danny Morrison at middle age.

Morrison is banned from America, despite invitations from Harvard. He tried to enter the country illegally to give a speech in 1982. Back then he was banned for being a Sinn Féin member. Today, ironically, Morrison is banned because he is not a Sinn Féin member (Sinn Féin officials receive waivers as a peace process incentive). This is a final “wall” that all concerned Americans should help bring down.

Leave a Reply