A revealing insight into the life of Irish actor Gabriel Byrne.

Gabriel Byrne is a paradox. Most articles focus on his dark, brooding persona while playing up his rugged, Celtic good looks, but to see him in person you’re struck by his gentle manner and keen sense of humor. And while there is no denying that he is a Hollywood star with all that that entails — homes in New York, LA, Dublin, a beautiful ex-wife, his own production company — he is also an accordion-playing father of two who really doesn’t seem all that interested in the fame game. During our interview at the Lobby Restaurant in New York’s Four Seasons Hotel, he spoke so passionately about subjects ranging from the state of Ireland’s film industry to the Catholic Church and an unsettling episode from his youth, that his much commented-upon sex appeal became a non-issue (well, almost).

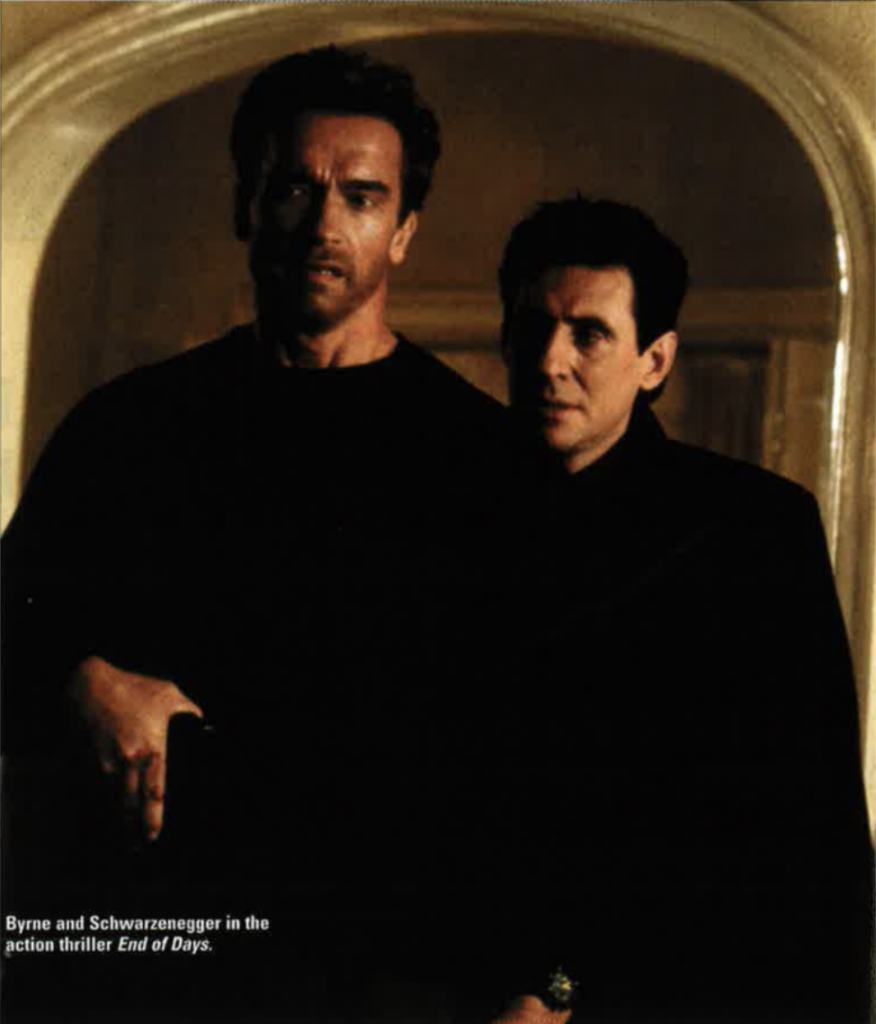

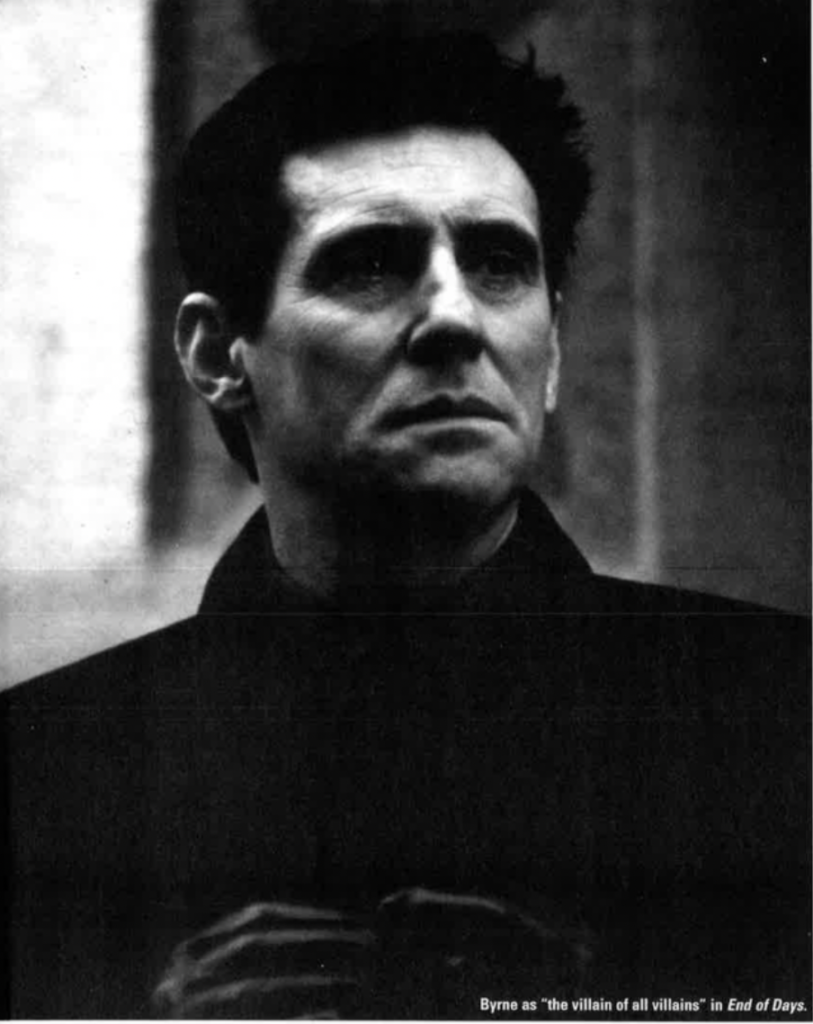

Byrne is in town to promote his latest movie, the Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle End of Days in which he portrays none other than the devil himself. I am his last interview before a car comes to whisk him to the airport where he’ll head to Paris for another round of press.

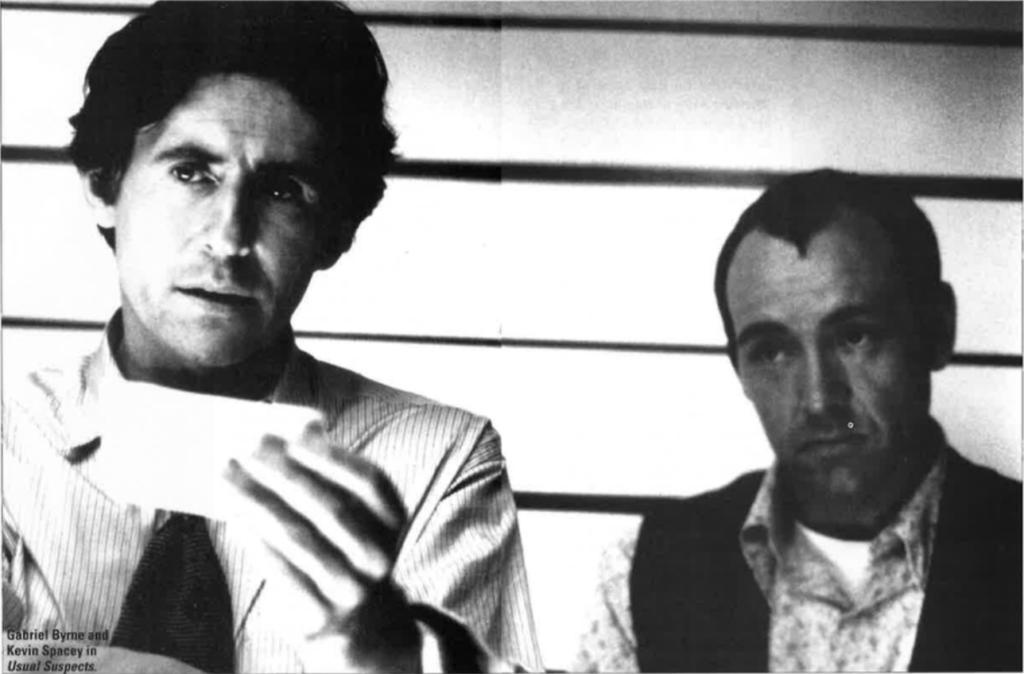

Though you get the sense that he is a little weary of talking about himself and perhaps putting up with fellow diners sneaking peeks at him, he is razor-sharp when the tape recorder starts humming. Since Byrne has passed up chances for big paychecks in action flicks like Patriot Games and Die Hard 2 to make more edgy fare (Miller’s Crossing, Usual Suspects), one wonders what prompted him to take the role of the devil this time.

He shrugs and says nonchalantly, “I didn’t find those other parts terribly interesting, to tell you the truth, but if you’re going to play the villain you might as well play the villain of all villains, Satan.” Mind you, he made sure not to play the devil with an Irish accent. “They always have non-American actors in the part of the villain because somehow it’s always perceived that the threat is from the outside,” Byrne says. “And it always has an accent.”

Though it clearly rankles him to have to constantly change his accent (he wonders how American actors would like it), he won’t mind brushing up on his American dialect for his next big role. Come this March, he’ll be starring on Broadway in a revival of Eugene O’Neill’s A Moon for the Misbegotten at the Walter Kerr Theater. Directed by Dan Sullivan and co-starring Broadway veteran Cherry Jones, Byrne will take on the challenging role of James Tyrone, Jr., a washed-up actor with a penchant for the bottle.

He is ecstatic about the prospect of doing Broadway for the first time. It was on the stage that he started his career some 20 years ago as a member of the hardscrabble Project Theater Company in Dublin alongside fellow countrymen Liam Neeson, Stephen Rea, Colm Meaney and directors Neil Jordan and Jim Sheridan — today’s who’s who of Irish Hollywood.

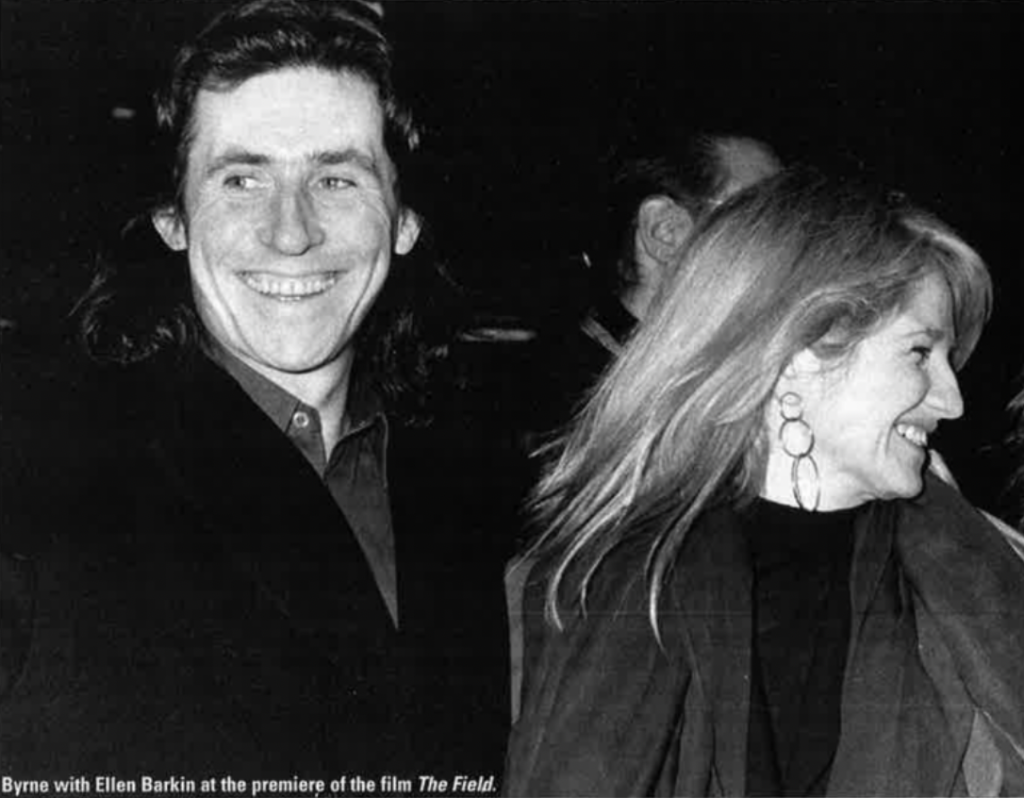

One of Byrne’s assistants approaches our table with a packet of photographs for him to look at. He flips through the stack quickly, indicating which ones should go to “Ellen” — ex-wife Ellen Barkin, with whom he has two children, Jack, 10, and Romy, 7.

Though their marriage has ended, the divorce was amicable. “As she is the mother of my children, I will never say a disrespectful word about her. I think we have a good relationship. I’m not saying it’s perfect — no relationship is perfect — but I wish her nothing but happiness and contentment in her life and I hope she has an extremely happy relationship with this new man.”

This “new man” is billionaire Ronald Perelman (who Barkin is this close to marrying), and though Byrne has met him only once or twice he has found him to be “a gentleman. Beyond that, I don’t really have any comment to make.” Once his assistant has flagged the photos, she makes her exit and Byrne picks up where he left off.

“I always had a yearning to go back to the stage. I love Eugene O’Neill, I’ve always loved Eugene O’Neill — his father was born in County Kilkenny.”

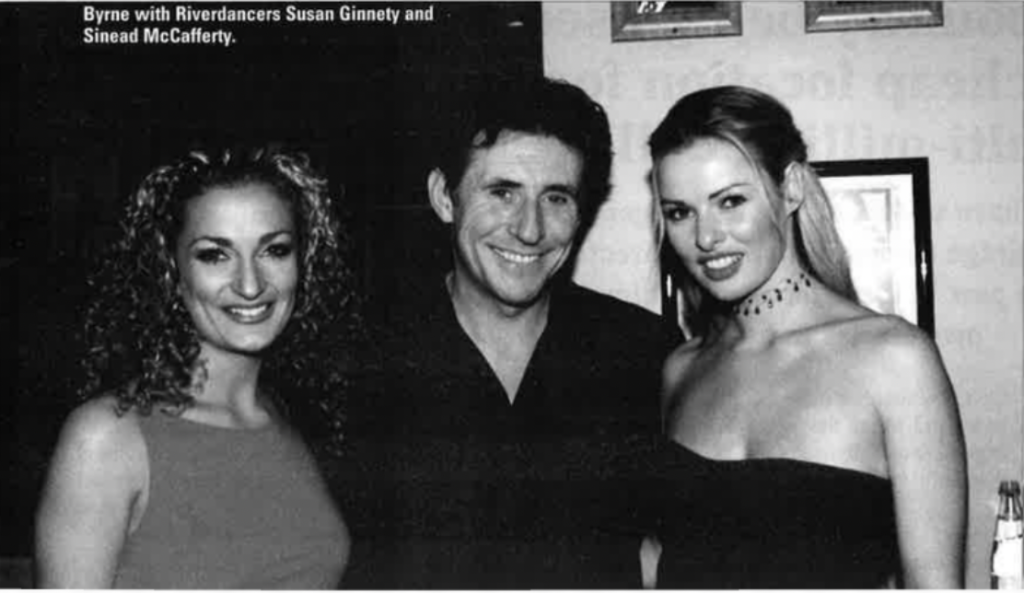

Noting that the play opens the same week as Riverdance makes its move to Times Square, he smiles and says, “It will be an Irish season on Broadway.” He is friendly with the creators of Riverdance, John McColgan and Moya Dougherty, and is thrilled with the ongoing love affair audiences have with the show.

“I was at the very first dress rehearsal in Dublin. It’s amazing that it started as a five-minute segment for the Eurovision song contest. It’s a wonderful success story, and now Irish culture is kind of sweeping the world — we’re not ashamed to be Irish anymore.”

As he gears up for the play, I wonder if he sought any advice from his buddy Liam, who has appeared on Broadway several times including a turn in O’Neill’s Anna Christie. “I spoke to him about it, yeah. He’s been very encouraging. I saw him when he was on Broadway and I recently said to him, `how the hell am I going to do it? I was so nervous for you and it wasn’t even me up there!’ And he said, `I’ll sit this time and be nervous for you.'”

Though he doesn’t see Neeson as much as he’d like, he does hook up with the old gang from time to time and he and Neeson are thinking of doing a comedy together later this year. The last time Byrne saw Stephen Rea, at the Deauville Film Festival in France, he was a member of the jury reviewing Rea’s role in Guinevere. “I said to him, `Ever think you’d see the day when I’d be sitting on the jury judging one of your movies?'”

Surely, when the young Gabriel Byrne was growing up in Dublin fascinated by the blue glow of televisions emanating from people’s living rooms, he could never have envisioned that he would make his living in front of the camera. Born in 1950 to a Guinness Brewery cooper and a nurse, Gabriel, the oldest of six children, had a pretty normal childhood.

During his summers in the nearby town of Ballitore, he would watch endless movies at the local cinema (usually Westerns or Hitchcock), then act them out in the fields. After attending a seminary in England for a few years, he returned to Dublin (the celibate life, the sixteen-year-old decided, was not for him) where he held a slew of non-glamorous jobs – morgue attendant and plumber to name a couple.

After graduating from University College, Dublin, he taught school for a while before catching the acting bug. At the unlikely age of 29, he took up the profession full-time.

Recalling his time at the Project, he said, “the actors who couldn’t get into the Abbey or the Gate because they couldn’t speak properly, or hadn’t gone to drama school, were all there. We were in the same little group on forty dollars a week. Nobody thought anybody would ever make a movie.”

Even now, he still seems a bit surprised at his success. His first taste of fame came when he starred in a popular Irish television series, Bracken, after which he returned to England to make several films including John Boorman’s Excalibur. As an outsider, however, he never felt at ease in the rigid British society of the time and found that many of the Irish stereotypes were being perpetuated in the London arts scene and so, before long, he headed to America.

Dozens of films later, Bryne is at the top of his game. He has worked with the biggest names in Hollywood (Jodie Foster, Kevin Spacey, Anjelica Huston, Brad Pitt), has branched out to producing (In the Name of the Father, Into the West) and now heads up his own production company, Plurabelle Films. Byrne is also a member of the Irish Film Board, and one of his goals is to maintain the integrity of the country’s film industry.

“I don’t think that it’s necessarily a good thing that Mel Gibson and Steven Spielberg came to Ireland to shoot Brave-heart and Saving Private Ryan. Spielberg shot there because it was cheap and he got to use the Irish army. I don’t like to see the country being used as a cheap location for huge multimillion dollar movies. We have to encourage the indigenous film industry; encourage our native writers, directors and producers to take part in the international film world, telling our own stories in a way that’s universal.”

He is strongly opposed to the ongoing trend of non-Irish actors taking prime Irish parts (think Meryl Streep in Dancing at Lughnasa and Emily Watson in Angela’s Ashes). “I’m tired of English and American actors playing Irish roles, because the reverse is not true. There are a lot of really brilliant Irish actors and actresses that never get a chance to do anything. Frank McCourt wrote a brilliant book that deservedly became a worldwide phenomenon. But is it fair to say that it’s an Irish movie? It’s directed by an Englishman – Alan Parker. It’s financed outside Ireland. The screenplay is by an American writer. It’s produced by an American. It has a Scottish actor playing the role of the father, an English actress playing the mother. Why could they not have made it with an Irish actor, an Irish actress and an Irish director? I’m not quibbling with McCourt or any of the actors personally, but you can’t be talking about an Irish film industry when we can’t even afford to make our own stories about ourselves.”

Though the film industry might be a work in progress, things have changed dramatically in Ireland in the last five years and particularly in his hometown, much of it due to the so-called Celtic Tiger. Byrne loves the new Dublin and tries to go back whenever he can. He also makes sure to bring along his kids so they can get to know the land of their ancestors.

“Ireland is extremely important to me, it’s my roots, but I think when people come from small towns to live in big cities they feel that sense of displacement, an inability to be part of society the way they had been; they just can’t really do it anymore.” It’s obvious he still feels that displacement, and though he has lived in Los Angeles for many years and now has an apartment in New York (to be closer to his children), it’s his house in the center of Dublin where he feels most at home.

He enjoys walking about the city. “People are very friendly,” he points out. “They’re supportive and encouraging. Sure, sometimes you meet the oddball, but that’s life.” Once in a while he’ll run into a former student from his teaching days and he’s always shocked to learn that many of them now have families of their own. He also appreciates the city’s new sophisticated hotel and restaurant scene.

“We never had the luxury of being able to really develop our cuisine, or our arts or our architecture. Irish cuisine was strictly utilitarian, it was about what you could plant and what you could eat. My God, I remember those hotels in Ireland where the food was expensive and abysmal – it’s so wonderful to see that all that has improved and we are very cosmopolitan. In ten years we’ve come leaps and bounds in the food department and in terms of services as well.” Patrick Guillbaud the French/Irish restaurant attached to Dublin’s Merrion Hotel, is one such place that he admires.

While he is pleased with the strides Ireland has made, he detects “a new side to our national character that wasn’t there before. We always prided ourselves on our sense of fair play and lack of prejudice, but we’re starting to see signs of racism,” he remarks.

“There’s also a certain cynicism creeping in and an obsession with materialism that didn’t used to be there. That’s all part of the Celtic Tiger. The division between the rich and poor is getting wider all the time, and there’s a lack of concern amongst a certain section of this newly rich.” That said, Byrne does applaud the fact that the Celtic Tiger has reversed the tide of emigration and more young people are now settling in Ireland.

The Church in Ireland has been taking a battering of late, and Byrne made the headlines recently when he admitted that he had suffered physical abuse at the hands of the Christian brothers and, later, sexual abuse by his Latin teacher while he was studying for the priesthood in England. When he heard that that particular priest had died, he felt compelled to write a letter to an Irish magazine, Magill. “It was the first time I spoke about it,” he says. “Obviously, I don’t want to be thought of in that way; there’s a degree of shame attached to it. But I came to terms with it a long time ago. In my opinion, society is only as sick as its secrets, and I think you have to speak out about it, because it’s only by facing up to these firings that you begin the process of healing and moving on. The thing is, you don’t do it so much for yourself as you do it for those other people who are keeping a secret.

“Pierce [Brosnan] came out and said that he had an awful time at the hands of the Christian brothers, you know. I don’t bear any resentment or hatred towards this man because I see him as much a victim as I was. The system and the Catholic Church are as much at fault.

“I believe the sexual urge is a sacred God-given thing, and I can’t understand why the Catholic Church insists on priests being celibate. To prevent that natural urge [means] it’s going to come out in perverse ways. Priests should be allowed to marry. As human beings we need the comfort and support of each other. Why should a priest be deprived of that? One of the most beautiful things in the world is the love of another person; why should anyone be deprived of that, or of what is possibly the greatest gift we have, children? Why should he be deprived of the other gift, sex? The Church says you have to give all that up, for what [reason]?”

Once Byrne went public on the abuses he suffered, he did not shy away from the fallout and he is angered that people haven’t necessarily embraced his candor. “They say, `Oh, why are you talking about that old thing again?’ I mean, why would I bring it up unless I thought it was important — like I need the publicity?” he says indignantly.

Another subject he is passionate about is the Irish Famine, and in particular the part he played in reading the apology from the British government at a Famine commemoration in Cork in 1997. “I thought it would be great if the British government just said `we apologize for what we did.’ It’s not that it’s going to change anything, but it’s a conciliatory gesture. The Celtic Tiger and the new image of the Irish is great but it’s taken us a very long time to come out of the shame of the famine and our definition of ourselves, and the scars that emigration left on our country.

“Yes, it [the mass exodus] helped build America, but people left their homes and never again saw their families. The Famine is our Holocaust,” he continues, his blue eyes lighting up with emotion. “It is our great national tragedy. [Tony] Blair had just come into power and he sent this letter that he wanted me to read. We were going live on television and just at that moment, the British ambassador showed up and demanded that she read the apology. I said I am an Irish citizen, and I’m reading the goddamn telegram from your goddamn prime minister and that’s all there is to it! Sorry. Goodbye. She didn’t even get into the building! After I read it, there was silence for a second, then a round of applause.”

It’s clear that Gabriel Byrne has plenty of interests outside the surreal world of Hollywood. But again, it’s that paradox thing, for a second assistant has approached our table and is trying to nail down Byrne’s contact numbers for his stay in Paris. He then casually mentions that he can’t find some shirts he left in his room (a suite, naturally). She is worded, considering he is leaving for the airport in less than an hour. When she persists in figuring out where the shirts could be, he backs off and you get the sense that he’s sorry he brought it up. He’s a star, but a reluctant one. I tease him for having two personal assistants, and he reminds me that most celebrities have much bigger entourages and often bodyguards (one can only envision what Arnold’s entourage was like during the filming of End of Days). It’s hard to imagine Gabriel Byrne surrounded by yes-men.

“I’m really lucky in that I have been able to do what I’ve wanted to do and I haven’t had to pay the full price that you have to pay to become a huge star. I don’t want to pay it and I never did want to pay it.”

It’s his kids that keep him grounded. Just before our interview he had been at a Thanksgiving drama in which his daughter played a pilgrim, no doubt an event that will present another batch of pictures to be sorted through.

“Fame is not a big deal at all,” he continues. “In fact, it’s a pain in the ass sometimes. My kids are not interested in that, and I don’t want them to be interested in that. This is a job that I do, one that I get well paid for, but beyond that, I don’t think about being famous from one end of the year to the other.”

In an effort not to get too wrapped up in the destructive Hollywood machine and to continue to challenge himself, Byrne has recently published a memoir called Pictures in My Head about growing up in Ireland. Along with gearing up for his Broadway debut, he is also overseeing his latest Plurabelle project, Mad About Mambo, which filmed in Ireland and starred Keri Russell.

He also loves dining out in New York City (his favorite restaurants are Nobu and Indochine) and when the mood strikes, playing his accordion — much to his children’s chagrin. With so much going on, you wonder if there’s time for a love life. “Are you seeing anyone at the moment?” I try to sneak the question in casually, but he’s not taking the bait. “I see a lot of people,” he shoots back slyly. “No, I’m not seeing anyone at the moment.” (Or anyone that he’ll admit to.) But no doubt, on A Moon for the Misbegotten’s opening night there will be a host of glamorous celebrities and Irish elite cheering him on. And while the reviewers will most likely zero in on his virile presence, Gabriel Byrne himself will most likely be concerned about whether his kids are old enough to see his play or the current state of the Northern Ireland peace process.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the February / March 2000 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply