As the thousandth anniversary of the Viking discovery of America will soon be celebrated in the year 2000, Thomas J. Martin and Donald V. Mehus examine the role that the Irish, with their own long seafaring tradition, played in those daring Atlantic voyages of exploration and discovery.

A thousand years ago one of the most remarkable discoveries of the European peoples came and went by virtually unnoticed: the sailor-explorers of northwestern Europe had discovered a new continent.

The year 2000 will mark the millennium anniversary of this great stride in human endeavors; and almost as unnoticed as it was a thousand years ago, the world may well have little idea of the significant Irish contribution to the Viking discovery of North America. To wit:

- Eleven hundred years ago, when the Norsemen first arrived in Iceland, a major stepping-stone to the New World, they encountered a colony of Irish monks already in residence there.

- Did the long tradition of the sea-roving Irish monks help lead the Norse sailor-explorers further westward, ultimately to North America?

- The ancestry of Leif Eriksson, credited with “discovering” Vinland (later to be known as North America), can be traced back to both Norwegian and Irish forebears.

- The first European child born in the New World, at the Viking settlement, was descended from Irish royalty.

- Old Norse historical and literary sources frequently credit people from Ireland and their descendants as major players in the Viking landfall on the shores of the New World.

- During the Viking Age, the Irish exerted further significant influence in Norway, Iceland, and elsewhere, helping to pave the way for Atlantic explorations.

The New Faith

As the year 1000 drew nearer, a new optimism, it was said, spread across Europe. In western Scandinavia, along the coast of Norway and as far south as present-day Göteborg, the Norse were turning increasingly toward Christianity.

King Olaf I Tryggvason of Norway (reigned 995-1000), who had long dwelled in Ireland, where he was converted by a hermit monk and later married a Christian Irish princess, Gyda, sought by both proclamation and coercion to Christianize his kingdom of Norway.

The implementation of the new faith, which encountered ready acceptance by some and strong resistance by others, was largely completed a few years later by King Olaf II Haraldson (reigned 1015-1028). Olaf was soon to be canonized and along with Saints Hallvard and Irish-born Sunniva venerated as Norway’s three patron saints.

With Christianity came an unprecedented interest in reading, writing, and learning. Scholars believe that it may have been the Norsemen’s increasing acquaintance with ancient Irish monastic literature, like that of the 6th century seafaring St. Brendan, which spoke of great lands that lay to the west of the known European world, which ultimately led to the discovery of North America.

Map © 2001 Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc.

Norse And Irish Worlds

The flourishing interaction between the Irish and the Norse in many other important ways was also of much significance.

It was in Ireland that the Norse established their largest and wealthiest urban colonies (their founding of Dublin dates from the year 841). During the 9th and 10th centuries, the Gaelic inhabitants and the Norse gradually began melding. This came about through extensive intermarriage and fosterage as well as through peaceful commerce, social intercourse, and political and military alliances.

Concurrently, Irish elements were influencing the Norse in craftsmanship, agriculture, art, dress, and much more. Similarly, the Norse had a major influence on Irish life.

It was Norse-speaking citizens who founded Dublin’s first parliament, the Thing (related in name to the present-day Nordic parliaments, Norway’s Storting and Iceland’s Althing), and who in 997 under the aegis of the Norse king of Dublin, Sigtrygg Silken-beard (reigned 989-1035), minted Ireland’s first coins.

The Irish, as we know from Norse as well as from Anglo-Saxon, Carolingian, and Gaelic sources, had long preceded the Norse sailors in voyages far into the western Atlantic. When the first Norsemen arrived in Iceland during the 860s, as the medieval Icelandic history of that country’s settlement, Landnámabók, tells us, they encountered a colony of Irish monks, whose predecessors had arrived on that bleak northern island up to a century or more earlier.

The Saga Island

When the Norse began to settle in Iceland in large numbers during the 870s, sailing primarily from Norway, Ireland, and the Hebrides, a good number of Irish immigrated to Iceland as well. Many Gads cane to Iceland as thralls of the Norse (slavery was common in those days), but many others, perhaps weary of the incessant feuding and warfare in Ireland, came of their own free Mill. While the number of these early Irish migrants during Iceland’s Age of Settlement (c. 874 to c. 930) can never be determined precisely, some authoritative estimates place the figure as high as 40%.

Numerous genetic and blood profile studies have concluded that the remarkable affinity between Icelanders and Irish of medieval times still holds true today, the peoples of the two nations being by most standard genetic measurements very closely akin to one another.

A visitor to Ireland or Iceland may make his own casual observation, for to be seen in each country is much the same proportion of red-headed, freckle-faced, blue-eyed people as in few other places.

Greenland

In the late 10th century, the best farming regions in Iceland having been taken up, sailors of Norse and Irish heritage from Iceland, ever seeking new land for settlement to accommodate a growing population, ventured from Iceland further westward to the desolate shores of Greenland.

On the southwestern coast of that mountainous, glacier-covered island, they established – under the leadership of Norwegian-born Erik the Red, father of Leif Eriksson – small settlements in the few habitable enclaves. Around 986, one Icelandic sailor, Bjarni Herjolfsson, who traveled in the company of pious Gaels, in attempting to reach Greenland, as the sagas tell us, was blown well off course; and when the fog finally lifted, the crew found themselves along the shores of a strange new land.

A Surprising Discovery

Gazing with surprise at this new, low-lying land – richly verdant with grassy meadows and abundant forests – Bjarni must have thought that this could not possibly be the stark, mountainous Greenland that he was seeking. Though his men wanted to go ashore to take on fresh provisions, Bjarni refused and ordered them to sail back toward Greenland. While Bjarni did not actually set foot on this new realm, as the Vinland Sagas recall (he had apparently sighted the eastern coast of Canada), Bjarni Herjolfsson is credited with being the first Norseman to set sight upon the New World – some 15 years before Leif Eriksson and five centuries before Columbus.

A few years later, around 999, Icelandic-born Left Eriksson, who had apparently inherited a zeal for adventure from his seafaring father, Erik the Red, decided to seek out this new land of which he had heard stirring tales.

First though, he is said to have visited Norway. Making a favorable impression on King Olaf Tryggvason, as the sagas relate, Leif was entrusted with the mission of helping to further the Catholic faith abroad and given the company of two young Gaelic thralls, Haki and Hekja.

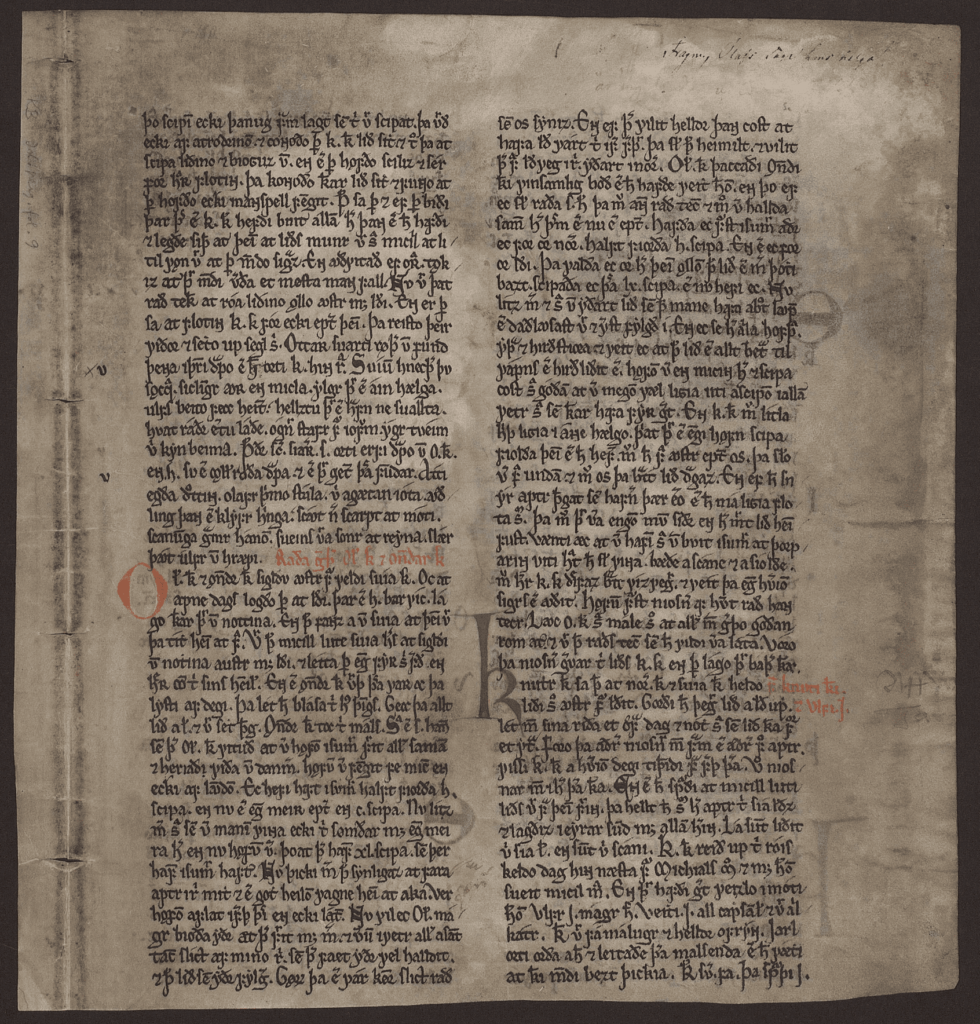

Back in Greenland, Leif carefully prepared an expedition and sailed westward around the year 1000 toward the new land. The story of his adventures are related in two famous Icelandic works, The Greenlanders Saga (Grœnlendinga Saga) and Erik the Red Saga (Eiríks Saga Rauða).

The Vinland Sagas

While there are certain discrepancies between these two Vinland sagas written many years apart (one is well advised to read the Icelandic sagas judiciously), they are considered the leading medieval sources of information on the discovery of Vinland and of the short-lived colony established there around the year 1000.

It is noteworthy that Erik the Red Saga both begins and ends with references to Ireland. The very first line mentions the Norse king of Dublin, Olaf the White, and after the voyage of Leif Eriksson to the New World, the sailors return with their great tales of adventure and discovery to Ireland – as the saga recalls – before the men realm to their home in Iceland.

These are but two of many references to Ireland and the Irish in the medieval Icelandic sagas. Such material has led eminent navigational explorers of recent times, like the great Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen (1861-1930) and the Icelandic-Canadian Vilhjalmur Stefánsson (1879-1962), among others, to conclude that Irish elements were very important in the Viking Age voyages of discovery to the New World.

Sea Path of Irish Monks

It is very possible, as scholars have suggested, that other Irish had previously discovered Greenland, a short distance away from Iceland, and then even gone on to the New World, a short sea voyage further still, well before the Vikings.

Reports of such Irish sea journeys to the west were related not only in St. Brendan’s Navigatio Sancta Brendani but also in the account of Cormac’s voyages in Adamnan’s Life of Saint Columba as well as in the work of England’s Venerable Bede (c.673-735) and of the eminent Irish scholar monk, Diculius, who flourished in the years around 800 at the court of Charlemagne.

Sea Path of Irish Monks

For more on this fascinating but little known topic of early voyages far westward into the Atlantic, the reader is referred to such classic medieval Icelandic works as the following. The first is Landnámabók, an authoritative history of early Iceland and of its Norse and Irish settlers, whose author shows a scrupulous concern for accuracy. The second is the Eyrbyggja Saga, which contains a remarkable passage about a seafaring Icelandic trader, Gudleif, who, sailing westward from Dublin around the 1020s, is lost in a storm and eventually arrives on the eastern coast of a New World land.

There, the saga relates, Gudleif meets an elderly Icelandic man, Björn the Breidavik-Champion, who had apparently long dwelt there among Irish-speaking people. While a reader is at liberty to regard the account of Gudleif’s adventure with some scepticism, we may cite a pertinent observation by a prominent 20th century historian-geographer, Professor Carl O. Sauer. Writing in his magnum opus, Northern Mists, Dr. Sauer concludes that Irish monks did in fact precede the Norsemen to the New World, suggesting that the Norsemen’s familiarity with the wandering Irish monks may very well have helped inspire the Scandinavians to follow suit.

“The thesis that there was a Christian and Irish colony overseas on the [eastern coast of North America even before the arrival of Leif Eriksson],” Dr. Sauer states, “gains credibility from the manner in which it was referred to in different [medieval] Norse texts, casually as a matter generally known might be.”

Greater Ireland (Írland hið Mikla)

Strong testimony to Irish elements regarding the New World appear in other Old Icelandic source material as well. Of particular significance is the fact that this new land – that is, an indeterminate area along the northeastern coast of North American – is frequently referred to by the name of “Greater Ireland” or “Ireland the Great” (Írland hið Mikla, in Icelandic), or by the name of “White Man’s Land” (Hvítramannaland), implying that these newly discovered lands were, in effect, closely associated with Ireland and with the white-robed Irish monks (thus “White Man’s Land”) dwelling among the indigenous people there.

Passages in the two Vinland sagas tell of exploratory forays on these shores by the two Gaelic thralls, Haki and Hekja, and by an older man, Tyrkir, during which they discovered wild grapes in the new land. These discoveries may have led Leif Eriksson to name this new realm “Vinland” (literally, “Wine Land”).

Scholars have long debated the exact location of Leif’s Vinland, setting its northern limits where grapes grow wild. But Leif or the saga writers may have – deliberately or inadvertently – given the impression, in order to make the new land seem more attractive, that delicious wild grapes were to be found almost anywhere along the North American coast.

Irish Royalty

Of further interest, as the saga literature relates, was the birth (c. 1009) of the first European child in the New World, a boy named Snorri Thorfinnsson. He was the son of the prosperous Icelandic leader, Thorfinn Karlsefni, and his beautiful wife, Gudrid. If the saga account is valid, then Snorri’s birth would have preceded that of the celebrated Virginia Dare (in 1587), the first European born in England’s American colonies, by nearly six centuries.

Young Snorri, as the Icelandic sources tell us, was of Norse and Irish extraction. The boy’s mother was a descendant of an Irish thrall, while his father was descended from Irish kings, most notably from Cearbhall (Kjarval, in Icelandic), the Gaelic king of Munster.

Leif Eriksson, born in Iceland c. 980 and claimed today by both Iceland and Norway (Norway was the natal land of his father, Erik the Red), must also have been influenced by his Irish heritage as well, being a descendant on his mother’s side of both commoners and royalty of lreland.

Leif, the sagas remind us, had a slave great-grandfather with a Gaelic name, Gils or Gilli (meaning “servant of’ and having a connotation of piety.) Gils was a common name in the western section of Iceland, where so many Norse and Irish had settled and from which area Leif and other Vinland explorers came.

One summer around 999, as the sagas further relate, Leif on his way from Iceland to Norway is reputed to have had a tryst in the Hebrides with a high-born maiden named Thorgunna. In due course a baby boy arrived and was named Thorgils, a name combining both Norse and Irish elements, Thor of course being a major – and favorite – deity of Old Norse paganism.

Patrekfjördur

It is worthy of note also that the last (and westernmost) fjord in view as sailors left Iceland headed toward Greenland and the New World was named for Ireland’s patron saint, Patrick: Patreksfjördur. The Irish elements of western Iceland are obvious to anyone familiar with the Icelandic family sagas. Here in these works we read of Irish ships loaded with Dublin cargoes sailing back and forth between the two Atlantic island realms, of Irish thralls, concubines, monks, sailors, merchants, and others – all clearly suggesting the degree to which by the year 1000 a Norse-Irish integration had already taken place in Iceland.

Nor is it any wonder, then, that sailing times across the Atlantic are often given in the number of days the voyage takes from Ireland, as in this example from the Icelandic Landnámabók: “From Reykjaness in the south of Iceland it is five days’ sail to Slyne Head in Ireland.”

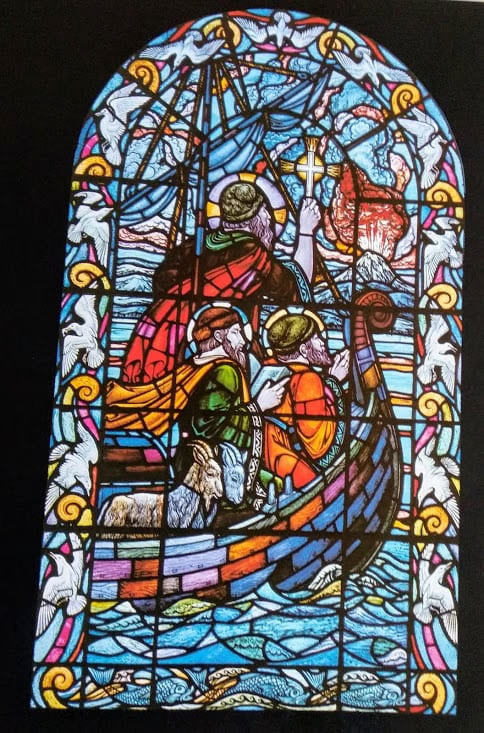

St. Brendan

Evidence brought to light recently may lend further support to views on the wide extent of the voyages of St. Brendan. Whether or not he and his fellow Irish monks actually reached the shores of the New World hundreds of years before the Norse arrived is still not certain. What is of great importance is that the accounts of St. Brendan’s voyages, whether real or legendary, served as a major source of inspiration for westward voyages for many centuries to come.

In the shadow of St. Brendan’s mountain homeland on the Dingle Peninsula in southwestern Ireland lay a Norse colony known as Smjörvík (from which the name of the locality today, Smerwick, is derived). One famous New World explorer, a contemporary of Leif Eriksson and Thorfinn Karlsefni, was Raven the Limerick Traveler (Hrafn Hlymreksfari), like other explorers very probably of mixed Norwegian and Irish ancestry.

Home in the Shannon-based Scandinavian Kingdom of Limerick, Raven would have heard tales in the Irish or Norse language of the great navels of the local St. Brendan, and these stories may have inspired him to set his sights and sails westward – just as they surely influenced many another Irish and Norse sailor

Canada’s L’Anse Aux Meadows

Recent archaeological excavations have shed new light on theories concerning Irish involvement in New World voyages of the Viking Age. In the early 1960s Norwegian archaeologists Helge and AnneStine Ingstad found at a place called L’Anse aux Meadows (located on the northernmost tip of the island of Newfoundland, Canada) what might be Thorfinn Karlsefni’s Vinland settlement, dating from the first decade of the second millennium.

One of the objects unearthed there that can definitely be ascribed to the time of the Viking Age is an Irish ringed-pin of the time used for fastening clothing at the shoulder.

Nationalistic Interests

At the time of the Vinland voyages, European borders were generally more fluid and the sense of national identity much less pronounced than today. This was certainly true of the Nordic people, who sailed and settled comparatively freely from one land or island to another.

In Ireland we find this fluidity in full sway, as Norwegian and Danish kingdoms flourished side by side with Irish kingdoms, their borders often shifting, the Scandinavians and the Irish constantly interacting and intermarrying. And Iceland, as we have seen, was created largely by a mixture of the Norse and Irish peoples.

Instead of regarding Irish, Norse, and Icelandic voyages as separate and competing endeavors, perhaps a more valid approach would be to consider all of these traditions as parts of one long complex movement conducted over a period of many years.

In this context it was the Irish monks who provided the first stage of an extended process of northwest European discovery and migration westward that in the opening decade of the new millennium reached its climax with the colony of Thorfinn Karlsefni on the shores of the New World.

The peoples residing along the seas of northwestern Europe share a most important related heritage as well: adventurous and skillful use of the stepping stone islands that led to the European settlement of a new world.

With the thousandth anniversary of the European discovery of North America fast approaching in the year 2000, the Irish and their descendants everywhere would do well to take an active role in the celebrations right along with the Icelanders and the Norwegians.

As the former Icelandic ambassador to the United Nations, Gunnar Pálsson, whose studies in medieval history were conducted at University College Dublin, recently commented: “This would seem to be a most fitting time for the Irish to foster a greater understanding of their own role in these voyages and of their contributions to the culture of Iceland, from where so many of the great adventurers of the Viking Age hailed.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the February / March 2000 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply