Michael Patrick MacDonald was in the third grade when the anti-busing riots broke out in South Boston in 1974. In his first book, All Souls, he harks back to that chaotic time. He talks to Lauren Byrne about growing up poor in Southie, that most Irish of enclaves.

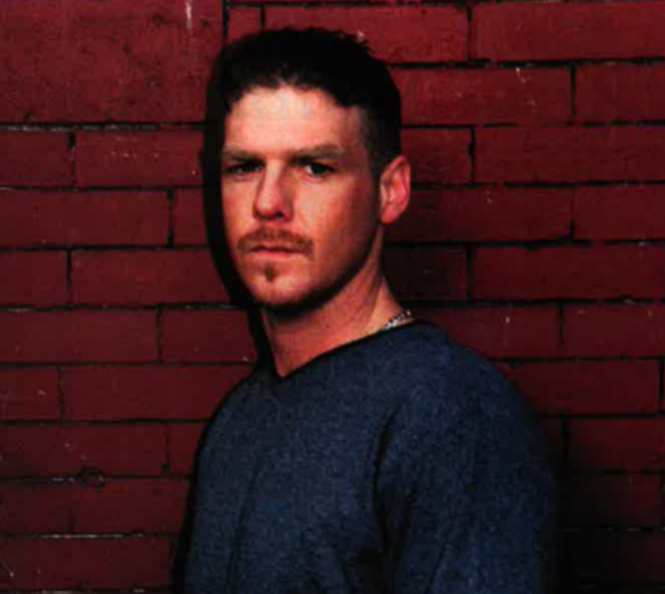

There’s a certain grim thrill in meeting a writer around whom reports are swirling that he is having to lie low because of death threats. In All Souls: A Family Story From Southie, first-time author and activist Michael Patrick MacDonald has taken the lid off life in the Irish American enclave of South Boston, known to the rest of the world since the anti-busing riots of 1974 as the heart of American racism.

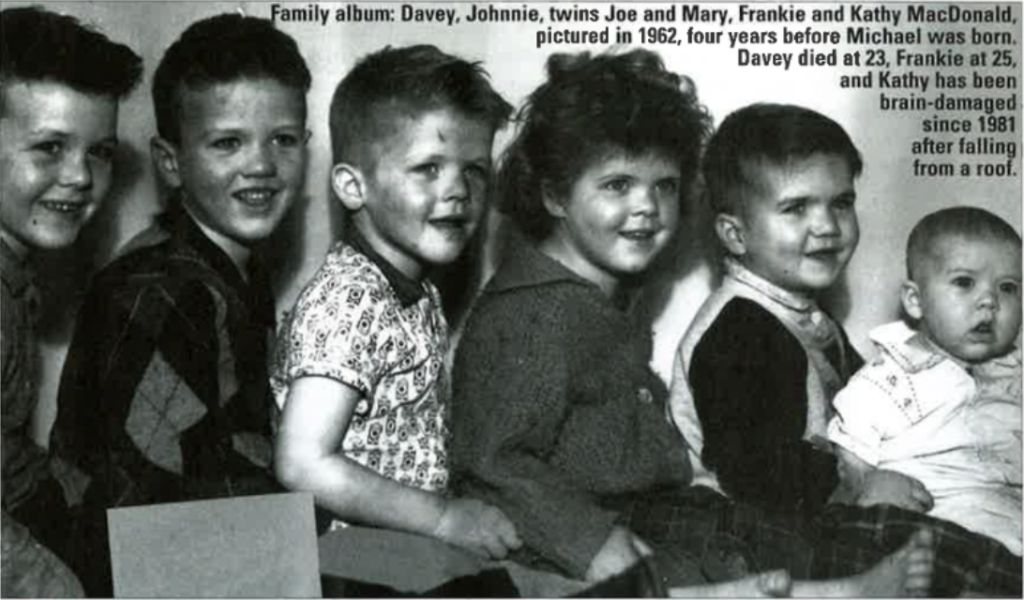

With his account of growing up in Old Colony housing project, where violence, drags and misfortune claimed the lives of three of his brothers and left a sister permanently brain damaged, MacDonald has offended the first commandment of Southie: Thou shalt not snitch.

He’s late arriving at his publisher’s office where we have agreed to meet. Detained by thugs on his walk from the row houses of South Boston to the red-bricked streets of Beacon Hill? But the 33-year-old MacDonald shows up complaining of nothing more than a bout of hay fever. So, you think, he’s either a brilliant actor or the most relaxed man on the planet.

The truth is a little less cinematic but not any less interesting. Demand for All Souls — only available in bookstores since late September — has been so great it’s already in its fourth printing. Meanwhile, his publisher canceled scheduled readings by MacDonald in the Boston area after trouble broke out at one such event.

“I got warnings that there was going to be trouble,” MacDonald says, throwing cold water on the more lurid reports in circulation. “It was neighbors. They were implying that there were going to be protests at readings. But I was on WRKO radio [recently] and every call was from Southie, and I was, `Oh God, what are they going to say to me?’ But every single one of them was positive. And the young people I’ve talked to have said they loved the book. That means the world to me.”

All Souls is the story Frank McCourt might have written had his family stayed in America instead of returning to Limerick. While Angela’s Ashes is the safe account of poverty left behind, MacDonald deals with Irish poverty in America, more annihilating perhaps because this is the land where dreams are supposed to come true.

They may have experienced the same kind of misery and prejudice as the black Americans but the early immigrant Irish wanted to be part of the white establishment, not the black underclass. In the end, Irish enclaves like South Boston were part of nothing.

So shrouded is the story of poor whites in America that when MacDonald gave readings in places like the South Bronx, African-American and Latino kids reacted with disbelief to his account of growing up as one of a family of 10 children in a crumbling, cockroach-infested project. He says, “They’re shocked to hear that story coming from a white person.”

“I love Southie. There’s no place in the world that has that sense of community,” he adds, displaying the kind of attachment that’s difficult to appreciate for the outsider who knows anything of Southie’s reputation.

But misery can breed the most intense kind of loyalty. Ostracized from the mainstream and not wanting to associate with the black underclass, the early Irish of South Boston transformed their isolation into a badge of pride and sublimated their misery in denial and silence. In more recent times, they even had their own folk hero, Whitey Bulger, who thumbed his nose at society by creating his own criminal empire. Whitey repaid the loyal Southies who kept quiet about his activities by supplying them with mountains of cheap cocaine, creating new levels of crime and violence in the already crippled community.

While he was still a young boy, MacDonald’s older brother Davey, a victim of schizophrenia, ended his own life. His sister Kathy tumbled from a rooftop after a squabble with a friend over drags, and the lengthy coma she fell into destroyed part of her brain forever. Kevin, charming, witty, a great scam artist, enjoyed a few bright years outside Southie before being drawn back into its crime world. He committed suicide after a visit from a police detective late one night at Bridgewater prison where he was serving time for robbery. And Joe, a successful boxer and the celebrity of the family, was murdered by his partners after a failed robbery. The attrition in the MacDonald family was staggering but not unusual. It was all part of growing up in Southie.

“It just came so easy and nothing else ever came my way,” MacDonald’s brother Kevin wrote in a farewell letter to his mother written before his suicide. He was talking about the open invitation to crime for a high school dropout living in a ghetto. In 1974, when liberal leaders decided to integrate the public schools, African-American children from project housing in nearby Roxbury were bused into South Boston. Kevin, Kathy and later, Michael, all dropped out of school as a result of the chaos that erupted.

They might have dropped out anyway, but it was that much easier when mothers weren’t prepared to send their children to schools where they were more likely to be beaten up than educated. “The mothers,” MacDonald records, “couldn’t get over people thinking that we had something in our schools that blacks in Roxbury didn’t have.”

The rage and violence that spilled out of Southie represented the frustration of a community being used as guinea pigs by liberals who were not busing their own children anywhere. The riots that followed put South Boston on the map and solidified the notion that the Irish had a preserve on racism.

“There was resistance,” says MacDonald, “because this was class discrimination and it turned into racism because it was manipulated by our own right-wing Irish American politicians who used it to launch their political careers. To the left we were always the people they had to break. Well, we were already broken, we were in the housing projects, our lives weren’t great. And then you had the right manipulating our anger and turning it into racism, and people followed, unfortunately, and threw rocks at the buses.”

MacDonald’s greatest achievement was in not taking the familiar route for project kids of drags, crime and early death. “I could have gone in the direction of drugs,” he admits, “but growing up I had an attraction to things beyond Old Colony project. As a teenager I was drawn to the arts and music, and I got into the punk rock scene, which was made up of people who came from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

“Another factor was the influence of my mother. I learned a lot from her about being proud to be different, because she was always stepping out of the mainstream. Ma grew up the daughter of immigrants, where it was all hush-hush about everything and the idea that you had a lot to be ashamed of, and she broke out of that mold. A lot of my values about race and that come from her.”

“All Souls is the story Frank McCourt might have written had his family stayed in America instead of returning to Limerick.”

Helen MacDonald is a first-generation Irish American. The story of her parents’ emigration is typical, and yet, like the stars in the sky, no two stories are alike. Her father, John Murphy, came from Kerry, one of three children born to John Murphy from Cordal, outside Castleisland, and Ellen Murphy from Knocknagoshel. The Murphys from Knocknagoshel were known as the Stunner Murphys for their looks, while Cordal was home to the Belter Murphys, renowned for their right hook; two qualities Helen MacDonald has always been proud to claim.

John and Ellen Murphy began married life in Cordal with a degree of comfort rare for their class at the turn of this century. They lived in a two-story house and owned a horse and trap. They were both literate and lent their skills to their neighbors, composing wills and writing letters for them. John Murphy often told his grandson Michael about his mother’s kind deeds, of how she used to wash and prepare the dead for burial and how she fed and gave work to the eight children of a neighboring single mother considered the shame of the parish.

When John Murphy was still in the womb his father died of consumption and the family’s fortunes began to decline. Later, the family’s cows began to die one by one of TB and so, at the age of 14, John had to set out to find laboring work wherever he could around Ireland. It was while he was on one of those trips that he got word of his mother’s death, the result of an untreated abscess. She was under the ground by the time he made it back home. His older sister Hannah had already left Ireland for Boston and was regularly sending money to pay the passage over for neighbors as well as family.

At 18, John received his fare from her and immediately set out, arriving in Boston in 1927 with no possessions beyond a leather pouch filled with religious medals and pinned with a photo of his mother that he wore around his neck all of his life and asked to be buffed with.

In an account that he wrote near the end of his life for an MIT professor, John Murphy described his life-long employment as a longshoreman on the Boston and Charlestown docks; he told of the uncertainty of the work, the long days, the physical dangers — especially for Murphy who had a fear of heights that he had to keep hidden or else risk his livelihood. Organized crime controlled much of the activity of the dockland but Murphy was proud to say he never “shook anyone’s hand,” a euphemism for falling in with the criminal class.

In his memoir, Murphy never mentions anything about his family life, nor of how he met his future wife at one of the dancehalls in Dudley Square in Roxbury, once a center of Irish activity, later the African-American neighborhood Southies so violently opposed having their children bused to for schooling.

An immigrant like himself, Brigid O’Donnell came from Carndonagh in County Donegal, and had found work in Boston as a maid. She was a reserved woman, her personality reflecting her family’s penchant for producing priests and nuns and, in one case, a bishop.

The couple married and went to live in Jamaica Plain, at that time the location of another strong Irish community, this one intent on achieving respectability and prosperity. The Murphys had five girls. Lacking a son — twin boys had miscarried — Murphy taught his eldest daughter, Helen, how to box. But it was not only in his memoir that he distanced himself from his family. In life too, he would never allow his daughters or grandchildren to be seen in public with him. An immigrant fighting to keep his place in the Boston docklands, where Italians, Poles and Irish vied for work, could not afford displays of softness or affection.

But behind the tough facade, the boy who had set out to fight his way through the world at the age of 14 still lurked. “He always needed reassurance,” Michael MacDonald says, remembering his grandfather. “He’d ask me what it meant to live a good life. I couldn’t imagine what it was like to come to that point in old age, but I’d try to figure out what it would be like to look back and be able to say you did your best. I was trying to make him feel good about being old and close to death. But he did feel enlivened by what I said because he did feel he’d done his best.”

“I have a mantle full of family treasures,” MacDonald says, listing letters and mementos he’s kept, including the accordions his great-aunt Hannah used to play. They are souvenirs of his mother’s side of the family. About his father’s side, he is less well informed, and happy to keep it that way. He was six years old when he discovered that he was not the son of Dave MacDonald, Helen’s errant husband who had faded from her life before Michael was born.

“The first time in my memory that I saw my father was in his casket. And even in his casket I was trying to find out things about him. It’s funny trying to study a corpse to find out things about them. I did cry, but it was kind of a release. Before it was this kind of unresolved thing and now, here he was in a casket and that was the end of it.”

George Fox, Michael’s father, and Helen MacDonald had a short-lived relationship. Fox, an engineer at the Charlestown Navy Yard, preferred the single life and never married. His parents, like Helen’s, were immigrants. His father was from Meath and his mother was a Kavanagh from Cavan.

“I was relieved to find out he was Irish,” MacDonald says. “I remember as a kid my brother Davey accusing me of being English. Of course,” he laughs, “the MacDonalds were Scots.”

In 1985, George Fox dropped dead at the age of 52 after ordering a round of drinks at his local pub. He had never acknowledged his only son.

“I feel like I’m from my mother’s family,” MacDonald says, explaining his lack of interest in the Fox side of him. “Blood doesn’t mean all that much when you think of it. The stories of my grandfather’s mother and father all kind of shaped me. Sure, you inherit things from both sides, but I like to think I come from my mother’s side.”

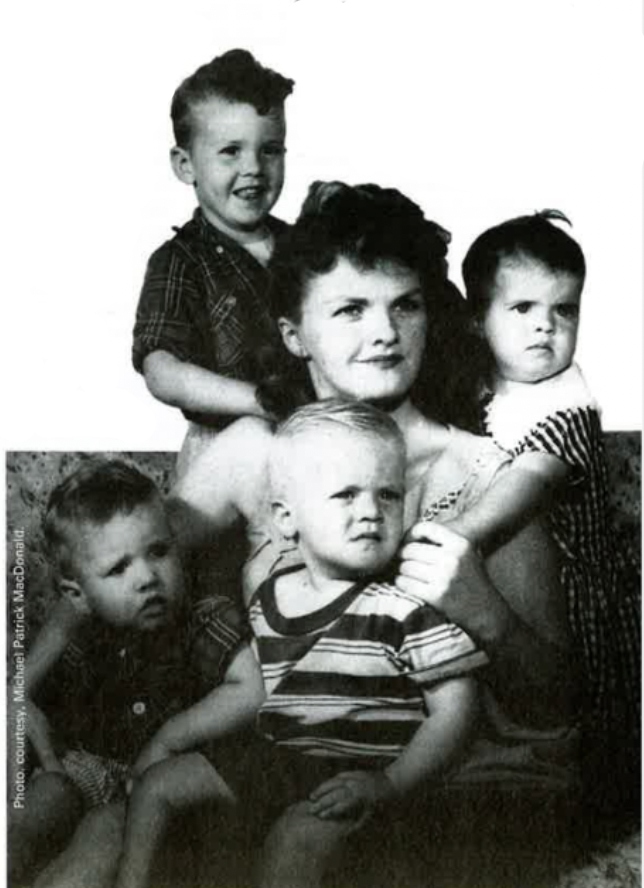

When they make the film of this book, as they’re bound to, Ma will be the plum role. The sorrowing Irish mother she is not. In her mini skirt and stiletto heels with her battered accordion slung over her shoulder, Helen MacDonald comes to life on every page: spirited, courageous, human.

It was her gumption and her kind heart that made the MacDonald name one to respected in Old Colony. When she finally escaped from Southie in 1990 with some of her children and a couple of plastic bags containing her belongings, she took on the State of Colorado and won her claim for better services for people like her daughter with brain damage.

“Birth control just didn’t exist for her,” MacDonald says, anticipating the question of why Helen MacDonald had 11 children (one baby died) in an age when contraception was so available. “She’s seen it all, but that’s still taboo. She was from Irish immigrant parents who came from a culture where to have more children was more beneficial. So she was living by the creed she inherited.”

Helen MacDonald’s personality was always a mix of innocence and rebellion, as much a clash of family temperaments as the result of being the product of two cultures. When she was 18 she visited Donegal, where she soon felt stifled among her mother’s quiet, church-going relations and ran off with a band of tinkers, making herself welcome by entertaining them with her accordion playing. News soon reached Boston of how she was disgracing the family with her wild ways and she was brought home. She never went back to her mother’s people after that.

Her lively spirits were more in tune with her Kerry relations, but even there she managed to raise some dust. On a visit to Cordal with her two eldest children in 1965 she fell out with a cousin and ended by accusing him of murdering his father. The town was up in arms and the body was dug up for examination.

“The stories of my grandfather’s mother and father all kind of shaped me. Sure, you inherit things from both sides, but I like to think I come from my mother’s side.”

But the investigation disproved Mrs. MacDonald’s theory and she was escorted to the airport by gardai (police) and told never to return. The kinds of tales MacDonald tells about his mother’s visits to Ireland make you wish that the likes of Synge or even John B. Keane had encountered her just once. Despite that episode and although the Murphy family are all now either in Galway or America, Helen still has many friends in Cordal and neighboring Castleisland, as Michael found out when he went there two years ago with her.

MacDonald has been to Ireland four times now. His first trip, he admits, was made under a certain degree of duress. “I didn’t want to go to Ireland,” he explains. “To me, at the time, the Irish were close-minded people, who didn’t want to see the world beyond their bigoted enclaves, but it was only by going there that I found out that that wasn’t what the Irish were about, it was just my experience of Irish America.

“I got to Paris in 1985 and I called my grandfather from there and said, `I don’t think I’m going to make it to Ireland,’ and he said, `You son-of-a-bitch, don’t you come home unless you go to Ireland.’ He was the one who only had bad things to say about Ireland. He had that love/hate thing that I have with Southie. `That old god-forsaken place,’ he called it because he didn’t want to think that he’d left something good. That was too hard. But when I said, `I don’t think I’ll make it to that god-forsaken place,’ his response was, `You’ll never come into my house again if you don’t.’ So I went and he was happy. We were very close.”

MacDonald’s most recent trip to Ireland was as a peace observer on the Garvaghy Road during the last marching season, revealing to him yet again the differences between the culture of modern Ireland and that of Southie, still living with a dream of the old country that no longer exists. “It was amazing because everyone up there looked like my neighbors, except that they were talking about their solidarity with black South Africans and how important the American Civil Rights movement was to them. And it’s such a relief as an Irish American to find out that not everybody who looks like you is racist.

“There’s such a level of conservatism among the young kids in South Boston. Anyone who does anything out of the norm, having different hair color, or a pierced eyebrow is a no-no. But when you hang on to the idea of an enclave it becomes a prison and the suicides had everything to do with that.”

MacDonald is referring to the epidemic of teenage suicides in Southie in 1997. Two hundred teenagers attempted suicide, ten kids died. They belong to an era that wants to speak out but doesn’t know where to begin. It is for the young people that MacDonald says he wrote his remarkably assured first book, to show them how to begin to address the violence in their own lives. “We’ve always had the highest suicide rate in Boston as far as I can remember, but during that five months, it was like an explosion. And I think it had everything to do with the history of South Boston, its history of suppression, repression, depression. Like me, a lot of people have survived a lot of traumas but haven’t been allowed to talk about it.”

MacDonald has been doing more than talking for some time now. Founder of the South Boston Vigil Group, he has also worked with Citizens for Safety and was involved in their successful gun-buyback program. His activism originated in another family tragedy. In an irony almost too painful to contemplate, his 13-year-old brother Stevie, pleading to be allowed to return to Southie from his new home in Colorado, wound up being arrested for the murder of his friend.

After he did time at the Department of Youth Services, Stevie’s conviction was finally overturned by the state appeals court after police tactics and Stevie’s inadequate defense were called into question. His young brother’s defenselessness in the face of, at best, shoddy police work and legal indifference shaped MacDonald’s current role as activist.

Things are somewhat quieter in Southie these days. Drags are still a problem, especially among the young, and a yuppie influx has increased rents and forced many of the old inhabitants out. But organized crime has fallen apart, and Whitey Bulger, now in hiding, was revealed to be the biggest snitch of all. It’s now known that he combined a successful career in crime with the role of FBI informant. His absence has left people freer to open up.

When MacDonald organized his first candlelight vigil to commemorate Southie’s victims of violence, he expected a few dozen people to show up at the church. Instead hundreds came, many acknowledging to themselves for the first time the pain of loss, admitting the defeat of the old ways of denial and silence, free to begin again.

Still the ghosts of the past linger. Doing an interview recently at a small New York radio station, MacDonald saw an ominously familiar face pressed up against the studio window. Whitey Bulger, he thought, his mouth turning dry, but on closer inspection he discovered it was Grampa Munster from the 1960s TV sitcom, now turned radio disk jockey. The past, it seems, is always with us.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the February / March 2000 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply