Collin Lacey interviewed author Morgan Llywelyn, who has created an entire body of work chronicling the Celts, and Ireland, from the earliest times to the present day.

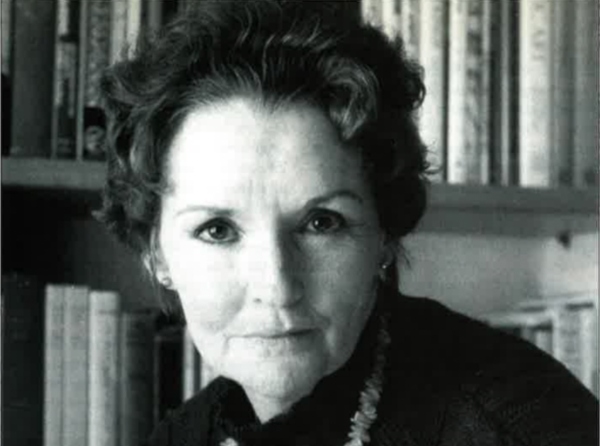

Brown eyes glinting in the low afternoon light, best-selling Irish author Morgan Llywelyn draws herself up straight in an armchair in her rural North Dublin home, and turns several shades of indignant. You get the impression that were you Unlucky enough to be on the receiving end, hers is the kind of righteous ire you wouldn’t forget in a hurry.

But it’s all entirely understandable. Authors and the books they send out into the world are just like the rest of us: they’re judged by the company they keep. And Llywelyn’s raft of novels, based largely on real-life characters from Irish and Celtic history, have been forced into keeping some pretty poor company.

“For some reason, my books invariably end up in the Fantasy and Science Fiction sections of bookstores,” she says, in a tone wavering somewhere between incensed and injured. “I have written some books in that genre but what people perceive as fantasy in my historical novels isn’t fantasy at all — it’s actually fact. Lion Of Ireland, for example, is about Brian Boru, and Strongbow is a fictionalized children’s biography of Richard DeClare, one of the great Norman warriors. These are real historical characters, and those who think the books are fantasy either haven’t read them or are very uninformed as to their own earlier history. To put them in the Fantasy section is not just laziness, it’s unfair both to me and to the people who read my books.”

Her exasperation isn’t reserved for booksellers who should know better, however. Although couched in terms that were anything but combative, a fan-maintained Llywelyn website on the Internet received a withering reminder from the author that “I don’t write Celtic fantasies. I primarily write mainstream historical novels about Irish and Celtic culture.”

“Pardon me if I sound angry,” the author continued. “But this is an old irritation.”

In a world where Fantasy is looked upon as an aberrant poor relation to ‘real’ literature, however, Llywelyn’s irritation is entirely warranted.

Lumping her books in the Fantasy and Science Fiction department of the bookstore is the literary equivalent of putting Roddy Doyle in Crime Fiction, Maeve Binchy in Horror and Edna O’Brien in Popular Thrillers. Not only is the classification incongruous, given the themes and deeply researched backgrounds that mark Llywelyn’s work, it’s also absurd.

So how did it happen? How did an author classed by prestigious industry magazine Kirkus Reviews as “a noted chronicler of Irish history and legend” end up sharing shelf space with Captain Kirk and the bug-eyed denizens of Dungeons and Dragons novels?

Llywelyn blames it on the druids.

“I suppose it began with Lion of Ireland,” she sighs. “Writing about Ireland in the 10th century, I had to address druids and druidism, which was then a very potent force here, so one of the two fictional characters in the book is a druid. Then in the next book I went back to examine the Celts in their earliest incarnation in the 7th century, and all the parts of Celtic belief about shape-changing and sympathetic magic. People who don’t realize that such things were an integral and authentic part of pre-Christian belief just took the books as fantasy. As soon as you mention druids, that’s how the book is classified. But it trivializes where we came from as a race.”

It also trivializes Llywelyn’s considerable achievements as an author. One of curiously few novelists mining the vein of such material, her books have woven a fictionalized tapestry from some of the most significant periods and characters in Irish history. Lion of Ireland, which sold 15 million copies worldwide, and its 1996 sequel Pride of Lions, brought to the page the life and chaotic times of Brian Boru; the historical migration of the Celts from mainland Europe to Ireland was chronicled in Bard: The Odyssey of the Irish; opening with the Battle of Kinsale, The Last Prince of Ireland went on to examine the attempts by Donal Cam, the O’Sullivan chieftain, to resist the might of the army of Elizabeth I, and the wonderfully-titled Grania: She-King of the Irish Seas recast the life of seafaring proto-feminist Grace O’Malley into a page-turner of significant charm and verve.

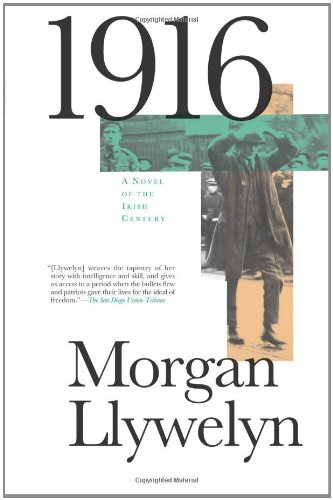

Llywelyn’s latest novel is 1916. Something of a departure in that it deals with events of a far more contemporary resonance than previous books, it focuses on the Easter Rising and features a cast of fictional and historical characters, including Padraig Pearse. The novel, which will be followed by two sequels based around the War of Independence and the establishment in 1949 of the Irish Republic, tops off what amounts to probably the most comprehensive fictional examination of Irish history ever attempted. Which isn’t bad for someone who only fell into writing by accident.

Born in New York — though family confusion permits her to claim her birthplace as “somewhere between Shannon and the States” — Llywelyn was raised in Texas by her mother, a Cork native, after she had separated from her father. A rare disorder, however, meant that the Texan heat affected the young Llywelyn’s skin, particularly during the summer months, so from an early age she summered with relatives from her father’s family in Mount Callan, Co. Clare. Spending most of her adolescence criss-crossing the Atlantic in search of a cool, shady place turned her, she says, into an outsider on both shores. But her time in Clare taught her one important thing: Ireland was the place where she felt most at home.

“Texas and Clare in the 1950s were two diametrically opposed cultures and climates, and it was a very strange thing to get used to,” she recalls. “Rural Clare was poor, empty, grey, and shabby, but most of all it was friendly. And in contrast to Dallas, which was the whole conspicuous consumption thing — it was another planet. I was caught between the two cultures, but the climate, pure and simple, made me hate going back to Dallas every year. Then when I would get back to Texas, I would talk about Ireland and about the landscape there, until I realized I was talking about and looking forward to going HOME to Ireland every year, so I suppose at some level I was always thinking about moving here.”

She finally moved permanently to Ireland in 1985, after the death of her husband, and in a gesture heavily laden with symbolism handed back her U.S. passport four years ago in favor of Irish citizenship.

But along with her status as a fully paid-up Irish citizen came one more thing to exasperate her — being described as an American.

“Still, when introduce people me as an American writer I just go up in flames, she says, with characteristic animation. “I’ll be stuck with it all my life at this stage, but I hate it.”

But at least she is a writer, which is something she says she absolutely loves. And bizarre it may seem from the perspective of her status as an author whose books have been translated into 27 languages, before she ever wrote a word of fiction she was on the verge of an entirely different career. An avid horsewoman all her life, she missed by half a point a place on the 1976 U.S. Show Jumping team that competed at the Montreal Olympics. She went along to the event as a replacement rider, but never got the opportunity to compete. Although she could never be considered a failure — she was among the top five competitors in the country — Montreal became a defining moment in her life.

“I’d been working towards that goal since I was fifteen years old, and I was tired. The fire in the belly was gone,” she says. “But I thought I’d go on riding and go on showing because all my life I had intended to raise horses. That was the ambition. My mother, seeing how frustrated I was at not having made the team, got me involved in doing family genealogical research to distract me. She was the family archivist. It was very meaningful to her, and she got me doing the research for her. And I found it all so exciting I was coming home at night and telling it to my husband about the Battle of Hastings and the ancestors of mine who had been involved. He kept telling me to write it down, so I wrote it down. When I had about 200 pages down, he said, `You’re writing a book. you should send it to a publisher.’ Of course I was saying, `I can’t write a book!’ but I sent what I had done to Houghton Mifflin in Boston, and they bought it by return post. Suddenly I was a writer, and nobody was more surprised than I was. So when people ask me how do you become a writer, I say `not the way I did!'”

Llywelyn’s first book, The Wind from Hastings, proved untypical in that it took as its background English history. It took her father to help her realize that she could do the same, and more, with the Irish history she loved so much.

“Dad was youngest of a very large family and had been a baby when he went to the States,” she says. “He was raised in that Irish American environment of the twenties and thirties that had turned its back on Ireland and was dedicated to being American. So his parents didn’t want to know about Ireland and didn’t talk to him about all those things. In retrospect, of course, he was there in the G.P.O. with Pearse, and nothing could have been farther from the truth! Although I gather from family stories that his father was quite a rabid republican in Clare, and that may have been the reason why he emigrated.

“However, he was not interested in Ireland at all, until The Wind from Hastings. When that came out Dad — who had since reunited with my mother — woke up and discovered, a bit late in the day, that he was Irish, and he was terribly incensed that I hadn’t written a book about Ireland. ‘Why don’t you write about Ireland? You spend all your summers there, you know more about Ireland than anyone!’ So I wrote Lion of Ireland, which was my second book.”

If only doing what your daddy tells you to could always prove so perfectly on the money. Published in 1980, Lion of Ireland quickly achieved international best-seller status, winning acclaim and awards wherever it was published, and Llywelyn, the woman who didn’t believe she could even string a few coherent sentences together, was suddenly on the map in terms of historical fiction. And with Thomas Flanagan, Leon Uris and Walter Macken the only significant writers dealing in a vaguely similar fashion with themes in Irish history, Llywelyn found out early that where subject matter for future books was concerned she had discovered the mother lode.

Consolidating the success of Lion of Ireland, Llywelyn has produced at least one book a year since 1980, not all of which have been historical fiction. Alongside the epic sweep of her historical work are Young Adult novels, retellings of Irish myths and legends, a history of Ireland in comic-book form, a pseudonymous contemporary novel, a biography of Persian king Xerxes that was commissioned by City College New York, and series a of solo and collaborative fantasy novels. Yes, those pesky fantasy things are fun to write, she says.

But despite the millions of words and the many plaudits they have earned, the impression is that Llywelyn might, just barely, have forfeited her long career if that was what it would have taken to get her most recent work published. Written in the run-up to the Good Friday Agreement, 1916 puts the fictional Ned Halloran alongside such key figures as Padraig Pearse, Eamon De Valera and Michael Collins in the maelstrom of the Easter Rising, and through him examines the historic and tragic events that constituted what she calls “the conspiracy of poets.”

In particular it is Pearse, the poet, schoolteacher, writer and philosopher, whom she singles out for praise. Indeed, in many ways the novel is something of a eulogy to the leader of the Rising, who was court-martialed and executed after the Rising. Alongside the rare and antique volumes that line the walls of her office — including valuable editions of the Book of Armagh, the Annals of the Four Masters, and Ancient Laws of Ireland — is an entire shelf devoted to writings by and about Pearse.

“Pearse is one of the most underestimated and most slandered men in Irish history,” she says, that fiery glint lighting up her eyes again. “He was an enormously complex and interesting character, a man We lost too soon. A man — and I say this with all due consideration — of the stature of Thomas Jefferson. I’ve read everything Peare wrote, all his collected letters, everything other people have written about him, and I’m convinced that if you read what he wrote and realize how drastically he has been altered in public perceptions you would have to agree. The sad thing you realize when you study Irish history is that we condemn our greatest patriots as madmen.”

Llywelyn’s 1916 opens with the sinking of the Titanic and ends with the sinking 18 months later of her sister ship, the Britannic. In between, Ned Halloran travels from Cork to New York and back again, finding his feet with the Irish Republican Brotherhood in Ireland as Peare’s most trusted messenger. It’s a story that binds the inexorable sweep of history to a story of passion, passionately told. As such, it’s vintage Llywelyn and was well received on publication earlier this year. Llywelyn declares herself happy with the book’s performance; in fact, she is happy enough with all of her books that she maintains copies of all of those currently in print at her home, which she also shares with seven cats and a dog named Whimsy. She has, she says, the kind of life she only dreamed of as a child flitting between Clare and Dallas.

Only one thing seems to bother her. It’s the old devil called Fantasy again.

“There’s a danger that the whole fantasy thing will trivialize what I’m doing with 1916 and the sequels,” she says. “And that would be a terrible thing to allow happen.”

So if you’re a bookseller and you’re reading this, drop everything right now and start fixing up your store. Get Morgan Llywelyn out of the Fantasy section, before Morgan Llywelyn gets to you first. You have been warned.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the February / March 1999 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply