Tim Russert was one of the most influential political journalists in America. As the former host of the top-rated Meet the Press, he could make and break careers, but his own success story is a highly unusual one. Niall O’Dowd interviewed him in Washington D.C. in 2000.

“He is absolutely the best, he does the most homework. In an era where everyone in the media is ahistorical and nobody knows anything, he knows everything. He’s very Irish in the sense that he has no pretensions.”

Fulsome praise indeed from acid-tongued Maureen Dowd, The New York Times columnist. Her comments about NBC’s Meet the Press host Tim Russert clearly show her regard for his work.

Tim Russert blushes when he hears those words read back. We are sitting in his modest office in the Washington NBC affiliate prior to our interview when I read the quote that Maureen Dowd gave me. Unlike so many of his television counterparts who project false modesty, Russert really seems ill at ease with any personal commendation.

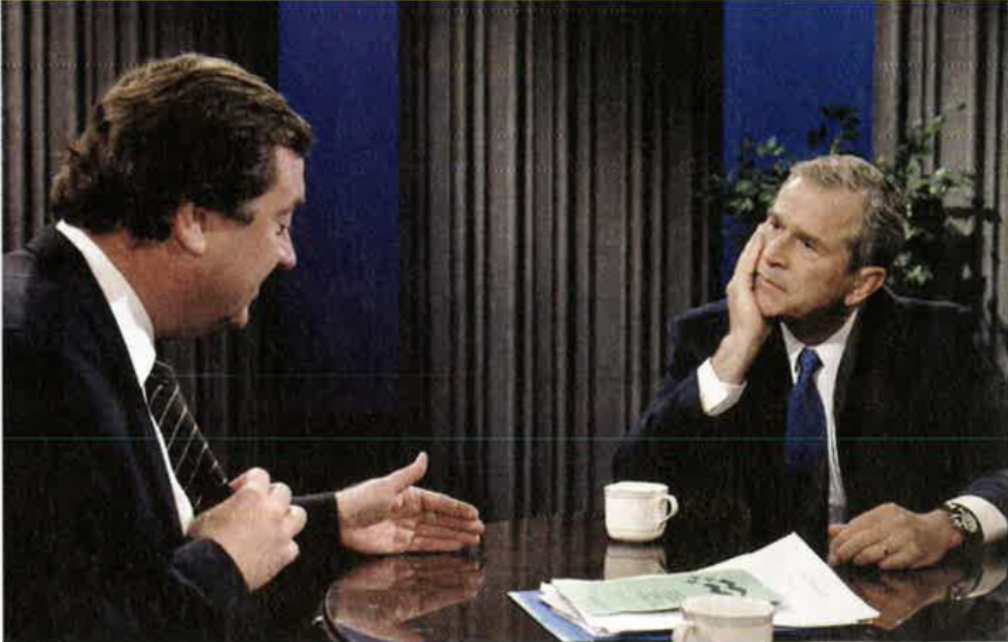

Despite the fact that he is host of the most influential political program on television, the one that outscores his rivals by three to one in audience figures, and is the most quoted show in television history, Russert is genuinely self-effacing.

Every week the great and the good and the not so good vie to appear on the program. During our interview he took a call from General Colin Powell’s representative. Shortly after, it was Michael Jordan’s man who called about a possible spot on a future show.

During the impeachment battle Meet the Press became the show of choice for millions of Americans because Russert, almost alone among reporters, never pontificated like so many other journalists on air, but let the two sides do the talking for themselves.

In an era of hectoring hosts who delight in shouting down guests even when they know little or nothing about the topic under discussion, Russert’s polite but probing style, backed up by exhaustive research, has proven extraordinarily popular.

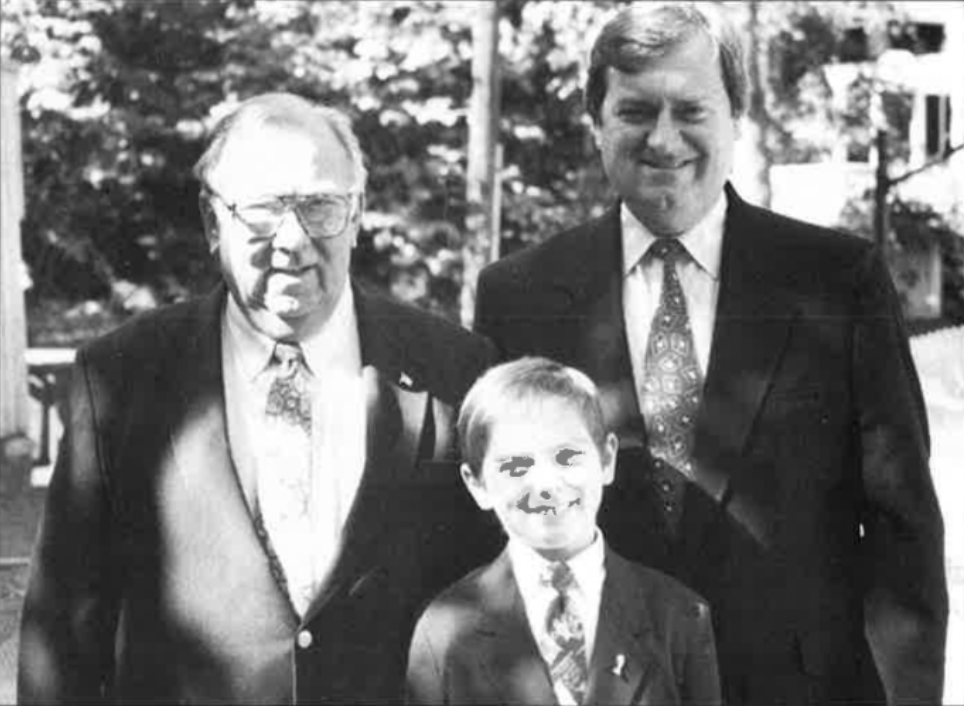

His office contains no inkling of the superstar status he has attained in network land. Family pictures of his wife, the writer Maureen Orth, and his 14-year-old son Luke dominate. The only concession to celebrity is a Parade magazine cover of himself with Luke in which he discusses fatherhood. Little wonder our art department had great difficulty tracking down good publicity photos of the Meet the Press host. They simply don’t exist.

Tim Russert gives the impression that he wants to stay grounded as the kid from South Buffalo, the working-class Irish neighborhood that he grew up in and that informs his every thinking moment. In a business full of hot air and pretensions Russert keeps those feet firmly grounded in South Buffalo soil.

His hero is not Edward R. Murrow but his 76-year-old dad Tim “Big Russ,” a former sanitation worker, still hale and hearty, who he calls up every Monday morning to go over the previous day’s show. One gets the sense that his dad’s opinion counts more than that of the network executives.

“He quit school in 10th grade to go fight in World War II. He came back, worked two jobs for 37 years, raised four kids and never complained a day in his life. He was a truck driver for the Buffalo News and a foreman in the sanitation department. On weekends he changed storm windows and did all the plumbing. That is the way it was.”

Russert’s mom, dad and three sisters, Trish, Kathy and Betty, still live in Buffalo and any time he needs a reality check he pays a visit. Then there are Diapers and Bottles Riordan, Shiny Faced Collins, Fuzzy Coughlin and a host of other South Buffalo characters who keep an eye on the Russert kid every week and make sure he’s not too big for his boots. Little wonder Russert stays grounded in that loamy soil.

It is fertile Irish country too. Tens of thousands of Irish moved to northern New York State following the railroads and the Erie Canal. Six of Russert’s eight great-grand-parents were Irish. He is descended from Gilhooleys and Rings and takes great pride in the fact that he is related to Christy Ring, the legendary Irish sports star whose skill at the ancient game of hurling for his native Cork matched Babe Ruth’s at baseball. The Russert name comes from the Alsace region on the French/German border.

Born in 1950, Russert grew up in a neighborhood where the biggest excitement by far was when John Kennedy was running for president. “Everybody in the neighborhood had Kennedy posters on their house,” he remembers. “When the results came in, the excitement was at fever pitch. I mean people went out on their porches celebrating and saying, `We won, we won.’

“He was Irish Catholic and one of us. For me it was so important because I now realized we could do anything. There were no more obstacles, no more limits.”

Just three years later Russert also remembers the saddest day of his young life. That was when Sister Mary Lucille came down the hallway in his school sobbing uncontrollably because Kennedy had been shot. “It was just devastating,” he remembers. “I was editor of the school newspaper and we wrote a special edition and sent copies to President Johnson and to Robert Kennedy.”

Sister Lucille played a large role in Russert’s childhood. Despite his working-class background she urged him to take the entrance exam for the Jesuit-run Canisius High School in affluent North Buffalo. He earned a half scholarship and worked to pay the rest of his tuition.

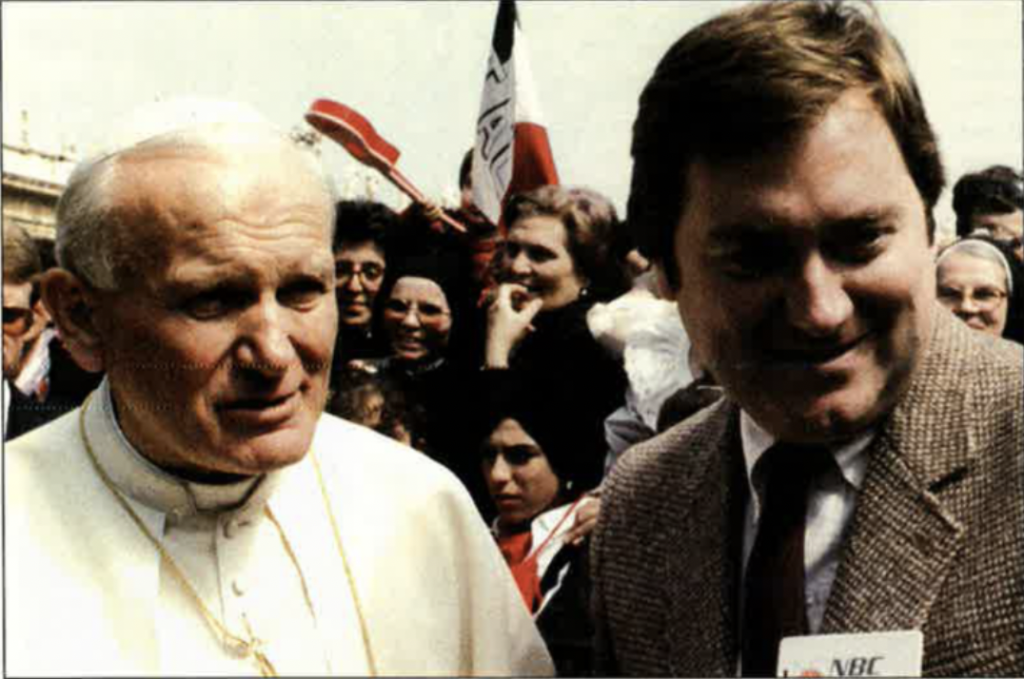

“I worked at St. Michael’s Rectory, a church in downtown that caters to the poor and the homeless,” he remembers. His affection for the church and his deep religious convictions continue to this day. He ranks his meeting with Pope John Paul II as one of the great highlights of his life. After high school Russert went to another Jesuit institution, John Carroll University in Maryland.

To pay tuition he worked every summer back in his old neighborhood. “I was a garbage man and also threw papers off the Buffalo News track. A hopper they call it. You jump off the truck and throw the papers. I also drove a taxi and made pizzas. All my college friends backpacked through Europe but I never did any of that. On spring breaks I’d teach in the Catholic grammar school for a couple of bucks — it worked for me.”

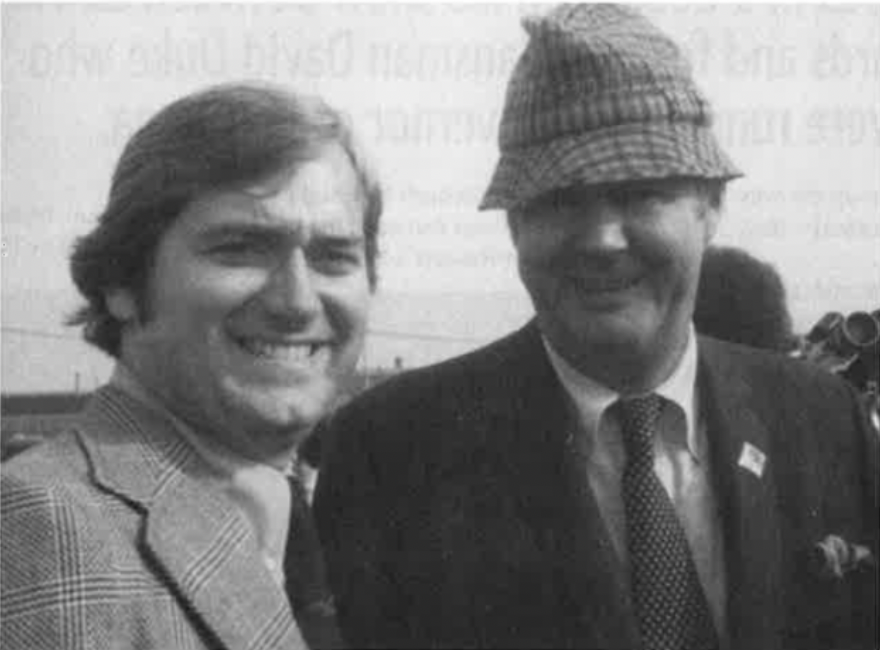

Between college and law school Russert worked as a full-time teacher and also had his first introduction to politics when he took a job with the City Comptroller of Buffalo, George D. O’Connell.

O’Connell was a legendary character who never missed a wake or failed to extend a helping hand to a family in need. In return he got their votes and ran an Irish machine, which was the envy of his opponents. Russert does not hold the fashionable view that all such machines were corrupt and in need of reform. “In the end it came down to a simple notion,” he says. “If someone plowed your streets, if someone hired your son for a summer job, if someone came to your father’s wake, people remembered it and they should remember it, and it’s all very honorable.”

In 1976 fresh out of Cleveland-Marshall College of Law and bitten by the political bug, Russert volunteered to work on the Daniel Patrick Moynihan campaign and became upstate coordinator. He was so successful that Moynihan and his wife Liz asked him to work with them in Washington, D.C.

As part of his responsibilities with the senator, Russert became involved in the Northern Irish issue and came to know SDLP leader John Hume. In 1980 he made his first trip to Ireland, North and South. It was an experience he will never forget.

When he landed in Belfast Russert says he “felt real trepidation.” John Hume had sent an associate to pick him up, but they were hardly on the road when they were stopped at an army checkpoint.

“It was such an awakening for an American. I was scrutinized, told to get out of the car, told to open the trunk. I kept saying, `I’m an American,’ but they looked at me like I was one of the locals. I guess with this puss it was hardly surprising [laughs].”

Later in the visit he took a long bus ride from Belfast to Dublin. “I loved it, just loved it. I had my face pressed against the glass the whole way watching and seeing everything. Then in Dublin I met with the Taoiseach [prime minister]. It was an interesting time.”

His fascination with Irish affairs dates from that period. In recent times he has had Sinn Féin’s chief negotiator, Martin McGuinness, on Meet the Press. The interest is also a family one: wife Maureen wrote a definitive profile of Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams for Vanity Fair.

Russert has kept a weather eye on developments in Ireland and discusses them knowledgeably. Last summer the American Ireland Fund honored him at their event on Nantucket island, which also featured President Clinton.

Back in the U.S. after his Irish trip, Russert left Moynihan and Washington D.C. to move back to his roots in New York State. He worked for then New York Governor Mario Cuomo for 22 months before he made the transition to television in 1984.

“I was going to go on and practice law but Leonard Garment, who was the counsel for Richard Nixon and a good friend of mine, asked me to have lunch with Larry Grossman who had just gone to NBC News. We got along very well and he said, `You know, you ought to come work for NBC,’ I was intrigued by the idea so I went to see David Burke, a friend who became the number two at ABC, and he said, `It’s a great business. All the skills you learned in government and politics are very applicable to what you will be doing.'”

For four years Russert was the executive in charge of the Today show in New York before moving back to Washington to run the bureau there, which is the biggest in the nation. Every day he would conference call with the news division and the anchors of Today and Tom Brokaw of the Nightly News.

His knowledge of what was going on in Washington — from the White House to the Pentagon to Congress — was so impressive that Michael Gartner, the head of news, said he was learning more from Russert’s one phone call than all the other news sources combined. “You ought to go on the air,” Gartner told him, and suggested that Russert be a panelist on Meet the Press.

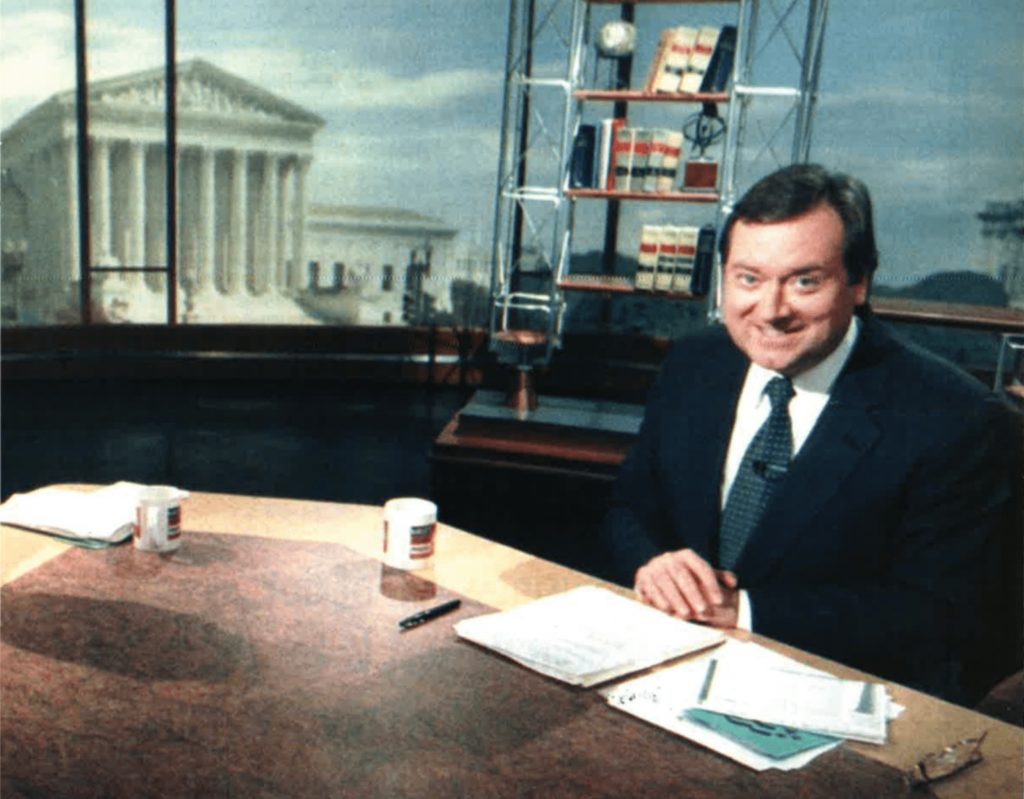

When the moderator’s job on Meet the Press opened up, Gartner insisted that Russert put his name forward, and so in December 1991 a 40-year-old on-air rookie commenced his new career. With his ruddy Irish face and blue-collar background, Russert was certainly not a “pretty boy” in looks or affectation and his lack of on-air experience made many wonder if he was the right choice.

He approached the job with typical thoroughness. The first call he made was to Lawrence Spivak, the founder of the program, the longest running on national television. “I asked him what he saw as the mission for the program. He told me to `learn as much as you can about your guest.’ If there is a way to sum up the way I approach the show, it is exactly that. Preparation.”

Maureen Dowd and others attest to Russert’s dedication to getting his homework in. He will often leave functions early on Friday to go home and bone up on his guests for Sunday’s show. He will spend endless hours going through politicians’ positions, often surprising them with a long-ago quote or different position they took on an issue.

Russert sticks to a simple formula. “Every Sunday I will sit across from someone and I will think of my dad and what he wants to know from this guy. I view myself very much as a surrogate for people who work all week and raise their families or are retired and don’t have the access or the exposure to all the information that I do. But if I can gather it all together and on a Sunday morning talk to the nation’s leaders in a way that people understand and that is meaningful to their lives, then I have accomplished it. Oh, and I will tell you, if something is funny, laugh. Don’t be afraid to laugh.”

The blue-collar approach has paid off in spades. Meet the Press extended to an hour in 1992 and under Russert’s leadership has buried ABC’s This Week and Face the Nation in the ratings. In addition, Russert’s weekly show on CNBC, also an interview format, enjoys a huge following.

As for the legendary Russert cool, he can only remember one time when he lost it. That was in a debate on his show between Edwin Edwards and former Klansman David Duke who were both running for the governorship of Louisiana. Russert asked Duke about his Nazi past and Duke got very upset. “Then I asked him to name the three biggest employers in the state of Louisiana, because he said he wanted to be an economic development governor. He couldn’t name any, and then I said, `Well, give me one. Give me one, Buster.’ I saw blood and I was going in for the kill. I watched the tape later that day and I said, `Oh, I wasn’t being a moderator. I was being a prosecutor.’

“I was talking to my dad the next day and I told him that I had made a mistake. He said, `Right, you made a mistake, but if you’re going to make a mistake, make it with a Nazi.'”

Coming from a World War II veteran, that was good enough for Russert. Coming from a South Buffalo man meant it played okay in the neighborhood too. Nothing else would have been as important to Tim Russert.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the August / September 2000 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply