John Hume, winner of the 1998 Nobel Prize, is interviewed by Kelly Candaele.

John Hume is the rarest of political figures. For over thirty years he has doggedly pursued peace in Northern Ireland, initially as a civil rights activist in Derry, his hometown, and later as leader of the largest nominally Catholic political party in Northern Ireland, the Social Democratic and Labor Party (SDLP). Over the years he has combined a practicing politician’s grasp of the immediate needs of his community with a strategic vision of how a deeply divided people could be brought around the table of peace. In Northern Ireland, this has been an all too unusual combination.

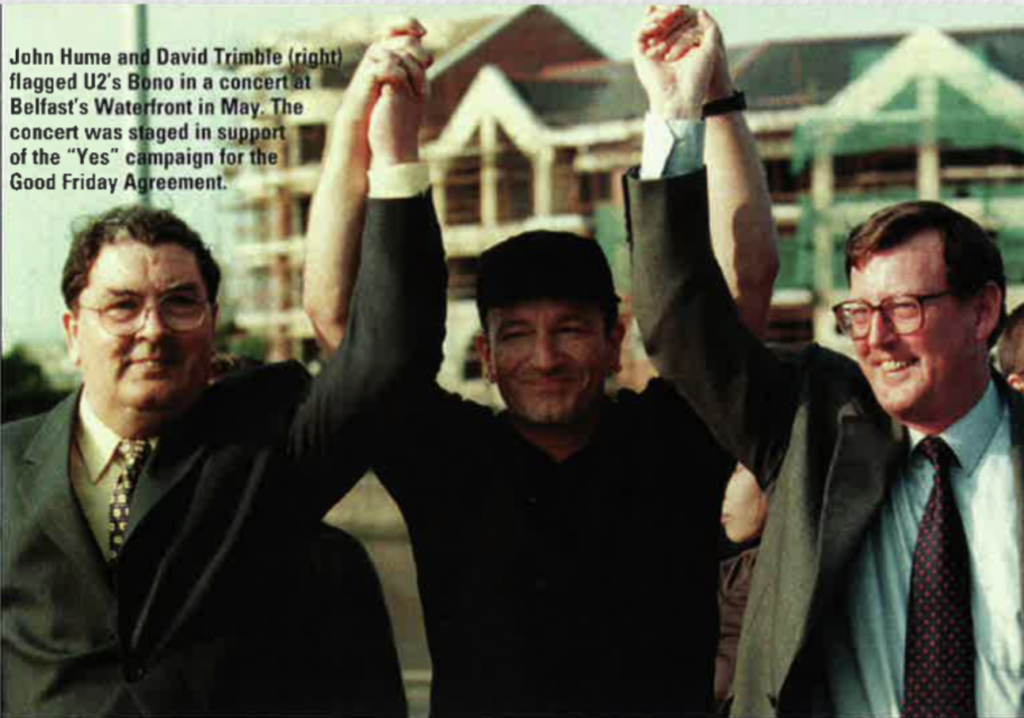

Hume’s fingerprints are all over the Good Friday Peace Agreement negotiated by American former Senator George Mitchell and signed by most of Northern Ireland’s major political parties in April. Twenty years ago Hume outlined a political scenario for peace: a power-sharing Northern Irish Assembly, a simultaneous democratic referendum of the people in both Northern Ireland and the Southern Republic, and cross-border political structures that linked North and South. He has consistently maintained that the ultimate political status of Northern Ireland should not be changed without the consent of the majority of its citizens. His 1970s vision is becoming today’s political reality.

In an area of the world where the bitter divisions of history have often been mediated by the bomb and the bullet, British troops and private armies, Hume has tenaciously articulated a nonviolent philosophy. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize last December, an award he shares with David Trimble, First Minister of the Northern Irish Assembly and leader of the Ulster Unionist Party.

Hume has not been universally admired. Visionaries rarely are. In 1993 after it was revealed that he was engaged in secret peace talks with Gerry Adams, president of Sinn Féin, the political wing of the Irish Republican Army, he was vilified in parts of the Unionist community and in the Irish press. Major figures in his own party turned against him. When party colleagues suggested that the dialogue with Adams would damage the SDLP politically, Hume responded angrily by asking if they “wanted to keep the party alive or people alive.”

Not surprisingly, both Hume and his family have been threatened with their lives. He has been hospitalized a number of times for exhaustion and depression. Pat, his wife of thirty-eight years, has suggested to him at times that “enough is enough.” But, she adds, “he had his own vision and thank God he persevered.” He was interviewed from his European Parliament office in Strasbourg, France.

Irish America: What were your initial feelings upon winning the Nobel Peace Prize?

John Hume: I’ve been extremely moved by the reaction I’ve received both at home and internationally. I had a standing ovation in the European Parliament this week from the representatives of all fifteen countries.

But I see it not simply as an award to myself but as a powerful statement of the international good will towards peace on our streets in Northern Ireland and good will towards all the people of Northern Ireland given what they have suffered over the last thirty years.

People in many parts of the world now look towards Northern Ireland as an example of how seemingly intractable conflicts can be reconciled. What can people in other areas of conflict learn from what has occurred in Ireland?

All conflict when you study it is about difference. Whether it’s your race, your religion or your nationality. And the answer to difference is not to fight about it but to respect it because difference is an accident of birth. In respecting difference, the best way to do it in areas of conflict is to set up democratic institutions which respect our differences but allow us to work together with one another in our common interests.

Those common interests are largely social and economic. We have to spill our sweat and not our blood. This way you build the trust and break down the barriers of centuries, which allows a new society to evolve based upon agreement and respect for difference. That’s what we are now doing in Northern Ireland.

How did you first get involved in politics in Northern Ireland?

I didn’t intend to get involved in politics. I was one of the first generation from my community to get free full time education. My parents could not afford to pay as my father was unemployed. Up until 1947 you couldn’t go to high school or the university here without having to pay for it. Nineteen forty-seven was the first year of scholarships and I got one. When I came back to Derry I thought I had a duty to those not as fortunate as myself. I got involved in community development through the credit union movement. We started the first credit union in Derry in 1960 and it’s now one of the biggest in the whole of Europe.

A number of commentators have pointed out that Martin Luther King Jr. was a great influence on you.

In the 1960s most young people in Europe were influenced by the civil rights movement in America and by President John F. Kennedy. I often quote King in my speeches given that we are a divided people. The quote I use most often is one he took from Mahatma Gandhi — “The old doctrine of an eye for an eye leaves everybody blind.” When you use violence in a divided society the other side retaliates and you’re into the doctrine of an eye for an eye.

Are you a philosophical pacifist or a pragmatic one in the context of Northern Ireland?

I believe absolutely in it. It’s from my experience in life and from the education I received.

Violence can be a very seductive thing. How do you psychologically overcome that desire for revenge?

Because the most fundamental right of all is the right to life. And therefore you cannot argue that you are working for the rights of other people and other human beings if your methods undermine the most fundamental right of all, the right to life.

You’ve focused on very concrete issues in Northern Ireland like the right to jobs, fair housing, economic development, rather than the issue of a united Ireland which has animated Sinn Féin and the Irish Republican Army. Why?

My father once told me you can’t eat a flag. If you cannot earn a living in the land of your birth and you have to go elsewhere to do so, then the land of your birth is not worth much to you. So the most important thing for people is that they have a decent standard of living and therefore it’s our duty to do everything we can to assure they’ve got it. And of course when they have that it’s a lot easier to deal with other problems.

We are about to do that now in Northern Ireland.

You had secret talks with Gerry Adams in 1993 about ending violence. What was it that gave you the sense that the IRA and Sinn Féin might be interested in an alternative political solution?

I knew that Sinn Féin and the IRA believed in what they were doing and were a product of Irish history. I felt that the reasons they were giving for their actions were out of date. So I asked them to state the reasons for their strategy. They said that the British were in Ireland defending their interests by force and therefore the Irish had the right to use force to put them out. My reply was that yes, in the past Britain came into Ireland originally because of Ireland’s links to European countries but that was no longer true in today’s Europe. Today’s problem of a divided people was a legacy of that past, but that couldn’t be solved by guns or bombs, it could only be made worse by deepening the division. That was the fundamental basis of the debate. Eventually I was asked to prove that the context had changed. One proof was to get the British government to declare that they had no selfish economic or strategic interest in Ireland and that the future of Ireland was a matter for the people of Ireland North and South. That led to the Downing Street Declaration by the British government, the ceasefires and the peace talks.

Photo: © Crispin Rodwell

You were vilified in the Irish press and even criticized by members of your own party for meeting with Adams. Was that the most difficult time in your political career?

It was a very difficult time because I did get a lot of abuse and a lot of criticism. While I’m a public representative I’m also a human being. But I knew what I was doing and I knew why I was doing it. Gerry Adams was engaged in totally genuine dialogue with me. If twenty-thousand British soldiers couldn’t stop the killing on my streets, I thought if I could stop it or save a single human life by direct dialogue it was my duty to do so. I privately felt there was a real chance of succeeding so I kept at it.

What major changes in the status of Catholics have taken place in Northern Ireland in the past thirty years?

When we started in the civil rights movement there were three basic reforms we wanted. We wanted one person one vote and we’ve got that. We wanted fair allocation of houses in the public housing arena. Now we have one of the best public housing systems in Europe. The third was fair employment. Unfortunately we have not been about to make the same progress on that front. The reason we haven’t is because of the violence of the last thirty years that has prevented us getting the inward investment that we needed. We are now going to work on that together, particularly with our friends in America. American companies who invest in Northern Ireland will be also be investing in the biggest single market in the world, the European market. That will be valuable for the healing process in our community. One of my dreams is to make the Foyle Valley in Derry, my city, the Silicon valley of Europe.

You have won this prize but there is not a permanent peace in Northern Ireland. There are still many critical issues including arms decommissioning that could derail the process. How do you make this peace stick?

I think we have got the foundations for lasting peace. I don’t like the comments of those who say we don’t. Those comments ignore the fundamental and historic things that have happened in Ireland. For the first time in our history the people of Ireland as a whole, North and South, have voted together with an overwhelming majority for this agreement as the basis for lasting peace. So anybody who seeks to overthrow that agreement seeks to overthrow democracy. The will of the people is strengthened by the Nobel award given to myself and David Trimble. I see the award as an award not to myself but to the people of Ireland.

You don’t agree with David Trimble that arms decommissioning should begin before Adams and other Sinn Féin representatives are admitted to the Executive Committee of the new government.

I think it should be done parallel to the implementation of the rest of the Agreement as the Agreement itself declares. This should be done to the satisfaction of all sections of the people which includes people Mr. Trimble represents. One of the aspects of the Good Friday Agreement is total disarmament. All parties have to do everything in their power to bring about total disarmament.

How important were Americans and President Clinton in pushing the peace process forward?

The role of President Clinton and the Americans was a very central one in this approach. President Clinton put peace in Ireland right at the top of his agenda and his support was very central to getting peace on our streets and reaching an agreement. Not only am I deeply grateful to him but the people of Ireland are as well.

Outside of the personalities involved — you, Trimble, Clinton, Adams, Tony Blair — as a trained historian what do you see as the historical flow of social and economic change that has created the context for the peace agreement?

We are living in a post-nationalist world today. We have moved beyond the nation state in Europe. That has changed the nature of our problem.

The Irish problem of 1998 is not the Irish problem of 1920 because in 1920 Britain had a definite interest in being in Ireland and staying in Ireland.

That is not so today. Today’s problem is a legacy of that past.

The reason the British are still in Northern Ireland is that they simply can’t abandon the Protestant community’s desire for continued union with Britain.

That’s right. They can’t abandon the identity, and neither can we, of one section of our people. If you want to solve a problem you start where you are, not where you’d like to be. Where we are is that there are two identities and we must accommodate and respect both. Out of that will evolve a new identity through the healing process.

You didn’t take a leadership position in the new Northern Irish Assembly. Why?

I’m a human being and there’s a limited amount of work that I can do. I’m a member of the European Parliament and it’s very important that we play a steady role there. I’m also a member of the British Parliament so I couldn’t take on any more work.

You’ve suffered from exhaustion and periodic depression. What personal sacrifices have you made from all of this?

I don’t think in those terms. I do my job.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the February/March 1999 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply