In the suburb of Rathfarnham an island of serenity exists amid the frantic bustle of 21st-century Dublin. With rolling lawns and woodlands embracing a handsome classical house, Saint Enda’s School harks back to a gentler time. In a place of honour facing the house is a large bronze bust of the school’s founder, Pádraig Pearse, who was more famously both the inspiration and the commander-in-chief of the 1916 rising.

It is the only statue to Pearse in the nation’s capital.

Born in Dublin in 1879, Patrick Henry Pearse bore the name of the American patriot (Patrick Henry) who said, “Give me liberty or give me death.” Pearse was the elder son of an Irish mother and an English sculptor father, who converted to Catholicism after his marriage. Patrick and his brother William — Pat and Willie to their family and friends — were given the best education their parents could afford. Only English history was taught in the British-run National Schools, but the Pearses sent their sons to one of the schools run by the Christian Brothers. There they were introduced to the Irish language and a flame was kindled in Patrick.

In 1896 he joined the Gaelic League, which was dedicated to the preservation and appreciation of the Gaelic culture. By seventeen he was an ardent Irish nationalist who signed his name Pádraig mac Piarais.

A shy dreamer, Pearse with great difficulty overcame an early stammer. On casual acquaintance people thought him remote. Only close friends ever saw flashes of a self-deprecating wit. He had the gift of inspiring great loyalty and devotion in those who took time to get to know him, however.

Pearse took a BA in law and was called to the Bar in 1901. A romance that ended with the death of his sweetheart, who perished while attempting to save a friend from drowning, may have been instrumental in Pearse’s sublimating his yearning for fatherhood into a wider experience. In 1905 he gave up his practice. Describing law as “the most ignoble of all professions,” he turned his sizeable intellect toward the field of education.

Already chief editor of An Claidheamh Soluis, the official organ of the Gaelic League, and author of numerous pamphlets, short stories and poems, Pearse began publishing essays on his educational theories. These were revolutionary for the time. In The Murder Machine, he condemned the educational system of the day as destructive to the human spirit. He wrote, “The school must make such an appeal to the pupil as shall resound throughout his after life. urging him always to be his best self, never his second-best self.”

In 1908 Pearse founded a school for boys, St. Enda’s, on the proverbial shoestring, and another school, St. Ira’s, for girls. Pearse’s writings tell us that he thought of the students as his foster-children in the ancient Irish sense. He was happiest in their company. Only with them could this intense, serious man relax. “I am a man with men but a child among children,” he wrote.

To read the writings of Patrick Pearse is to touch the soul of the man. His style is idealistic, even naive by modern standards, reflecting his innate innocence and that of the era in which he lived. But the writing is lucid and its meaning always clear. He said what he meant and meant what he said.

Pearse endowed his charges with the Gaelic ideals of strength and truth and the Christian ethos of love and humility. Of equal importance with scholarship were self-reliance, personal responsibility, and a strong sense of morality. Courtesy and kindness toward one’s fellow creatures was demanded; the only boy ever expelled from St. Enda’s was guilty of cruelty toward a cat. The ubiquitous corporal punishment of the time was noticeably absent; students were on the honour system. Learning was made a joy rather than a chore.

Finances were always a problem. St. Ira’s eventually had to be closed, but Pearse fought hard to keep St. Enda’s going. To raise funds he wrote heroic plays, which he produced with the help of his brother Willie. St. Enda’s boys even appeared at the Abbey Theatre in plays by Pádraig mac Piarais.

Anything a man might need to know in later life was taught at St. Enda’s. Pearse intended to produce well-rounded human beings capable of performing to their maximum potential…in a free Ireland. He wrote, “I plead for that true freedom which exists in fact because each, valuing his own freedom, respects also the freedom of others.”

Meanwhile, this gentlest of men was preparing his students to fight for their country’s independence.

In 1913 Pearse joined the militant secret society called the Irish Republican Brotherhood. The next year he visited America to raise funds for his school. Under the sponsorship of Irish republican John Devoy he addressed Irish American groups whose generosity enabled him to send money back to his mother and Willie, who were managing St. Enda’s in his absence. Pearse’s impassioned oratory not only benefited the school, but also won new friends for the struggle for Irish independence.

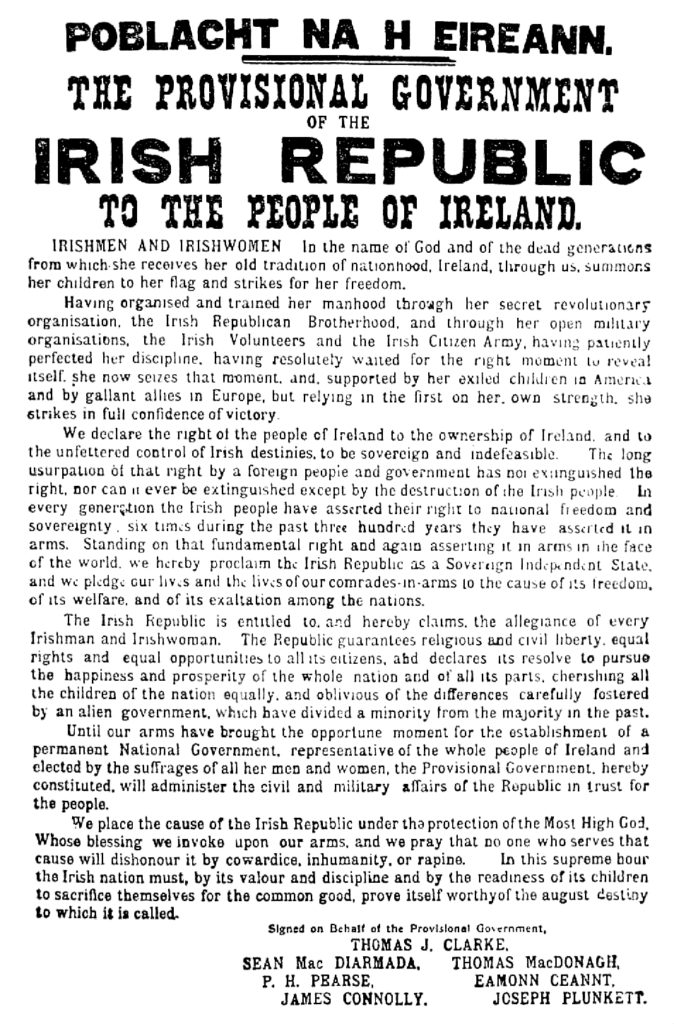

The time was fast approaching to put deed to word. With the founding of the Irish National Volunteer Corps in 1914, a nationalist militia was created. Men flocked to join; the Volunteers soon numbered tens of thousands. Many of the leaders were members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. The organising director was one P. H. Pearse.

At the graveside of the old Fenian hero, O’Donovan Rossa, Pearse gave an oration that would be memorised by generations of Irish schoolboys. The final lines ring down the years: “Life springs from death, and from the graves of patriot men spring live nations. The fools, the fools! They have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace!”

The spark he kindled burst into flame in Easter Week, 1916.

In the aftermath of the Rising, Pearse was acclaimed as one of Ireland’s greatest patriots, a man who had gone to his death willingly that future generations might live free. But the anti-nationalist propaganda machine went into overdrive. Every sort of accusation was hurled against the executed leaders, Pearse in particular.

In his essay The Coming Revolution, written in 1913, Pearse had stated, “A thing that stands demonstrable is that nationhood is not achieved otherwise than in arms. Ireland unarmed will attain just as much freedom as it is convenient for England to give her. We must accustom ourselves to the use of arms. Bloodshed is a cleansing and a sanctifying thing, and the nation which regards it as the final horror has lost its manhood. There are many things more horrible than bloodshed; and slavery is one of them.”

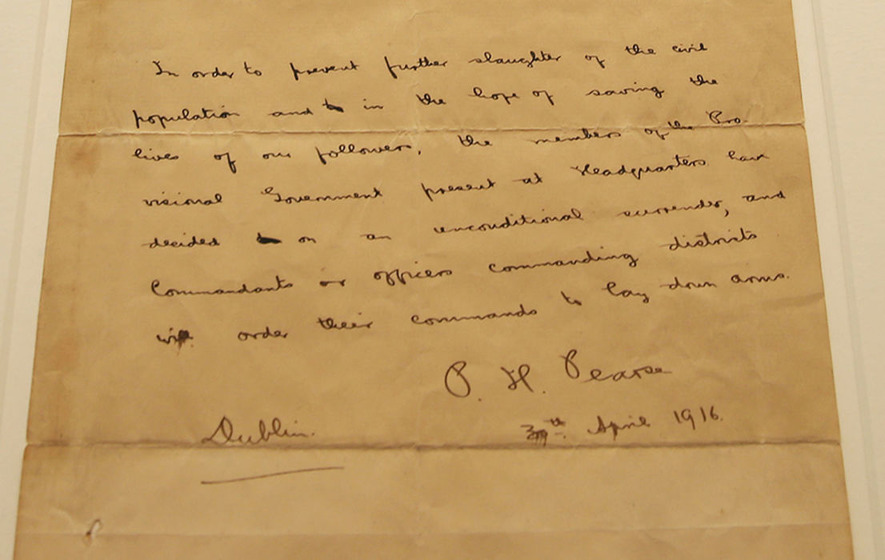

Deliberately misconstruing his words, after the Rising the British press depicted him as a raving lunatic eager to wade in blood; Pearse, who carded a revolver throughout Easter Week but never fired a shot, and finally surrendered to spare the lives of the Dubliners who were being slaughtered by British artillery. Pearse had hoped to sacrifice no life but his own for Ireland.

The virulence of the attacks against Pearse after his death are a measure of the threat which he represented in the minds of the British establishment of the time. One can kill the dreamer but not the dream, and his dream was dangerous to British imperialism, which was already under pressure in India and elsewhere.

Those who knew him acknowledged Pearse to be highly strung, often impractical, but possessed of the highest integrity. This integrity was the strength underlying the man. Pearse’s secretary, Desmond Ryan, summed him up: “No honest portrait can hide certain shadows, (but) he was a man whose faults were the defects of his straight and rigid virtues. He had no petty vices nor meannesses. To know him was to love him, to be inspired and see a glamour in the most humdrum details of ordinary life, a sanity in the most hazardous enterprise. He hoped for the best and dared the worst.”

Even the presiding officer at Pearse’s court martial commented afterward, “I have had to condemn to death one of the finest characters I have ever come across. There must be something very wrong in the state of things that makes a man like Patrick Pearse a rebel. I do not wonder that his pupils adored him.”

As Pearse sat in his cell awaiting execution, he wrote a letter to his mother which concludes,

“We have done right. Do not grieve for all of this, but think of it as a sacrifice which God asked of me and you. I have no words to tell of my love of you, and how my heart yearns to you all. I will call to you in my heart at the last moment.”

Then he penned a poem called “The Wayfarer”; his farewell to life:

“Sometimes my heart hath shaken with great joy

To see a leaping squirrel in a tree,

Or a red lady-bird upon a stalk,

Or little rabbits in a field at evening,

lit by a slanting sun…

Or children with bare feet upon the sands

Of some ebbed sea…

Things young and happy

And then my heart told me: These will pass,

Will pass and change, will die and be

no more.

Things bright and green, things young

and happy,

And I have gone upon my way

Sorrowful.”

A few hours later a British bullet sent the wayfarer on his way.

For half a century Pearse was foremost in the pantheon of Irish heroes. In 1966 RTE, the Irish National Television network, celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of theRising with a powerful drama series called Insurrection. Deeply moved audiences applauded scenes in which Pearse and his companions defied the crushing might of the British Empire and faced execution with awesome courage.

Then came 1969 and the Troubles. The republican movement of which Pearse had been the shining inspiration became linked in the public mind with modern terrorism. The old charges were exhumed by revisionists and new ones made. The name and reputation of Patrick Pearse were systematically blackened.

Yet to blame Pearse for the situation in Northern Ireland over the last thirty years is tantamount to blaming Thomas Paine, whose writings helped inspire the American Revolution, for U.S. government policy in Viet Nam. However, such is the power of the printed word, and the constant drip-drip of repetition, that since 1969 Patrick Pearse has almost disappeared from the national consciousness. If, like Thomas Jefferson, he had survived his revolution to become a leader in the fledgling republic to which it led, how different things might have been.

Three decades of political expediency and revisionism have denied the Irish people their justified pride in this extraordinary man. Pearse cared passionately and was willing to put his life on the line for an abstract ideal. But the patriotism he espoused has gone out of fashion. Today the majority are passionate only about the acquisition of material goods and status symbols. Forgotten is the greatest status symbol of all, one that Patrick Pearse possessed in full measure: nobility of spirit.

Leave a Reply