William Penn (1644-1718), the founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, promoted principles of freedom that helped lay the framework for First Amendment religious liberty. Before emigrating to America he was imprisoned in Ireland for his beliefs. Clara Pierre traces the history and roots of the Quakers in Ireland as she traveles around the country in the footsteps of Penn and his followers.

Few American travelers touching down at Shannon Airport are likely to know that the airfield adjoins an estate once belonging to the family of William Penn’s mother.

In fact, one hardly thinks of Ireland – any part of it – as Quaker territory. Yet there are areas in the south, particularly in County Cork, that are resolutely linked with the Society of Friends.

Touring Penn country provides the historically curious visitor with an unusual slant on some of Ireland’s lushest countryside. In four days of leisurely automobiling, it is possible to cover the major Penn landmarks and Quaker (Society of Friends) sites across County Cork and to venture up into the soft rolling landscapes of Tipperary and Kildare before ending the tour in Dublin. Stopping at sleepy villages, thriving market centers and seaside ports along the way is part of the charm of seeing Ireland with a purpose in mind – a purpose flexible enough to give way to detours. This way of inviting oneself into the heart of a country may lead to some unexpected insights into its past – in this case, into the lives of early Quakers, particularly that of the region’s most prominent figure, William Penn.

There have been Quakers in Ireland since the mid-17th century, most settling in the Protestant north. Refugees from the religious persecutions of the Cromwell years, these small bands of dissidents sailed from England to escape the law: many early Quakers had already been jailed for insisting on public worship, refusing to take oaths, serve in the army, or pay tithes to the Church of England.

Once on safer shores, many Quaker families migrated to the gentler and more temperate south, some making Cork their center, others progressing to the southern-most reaches of the seacoast. All seem to have continued in their modest trades: Goodbodys settled in the midlands as jute and sack-makers; Mosses drifted south to Bennet’s Bridge in County Cork to set themselves up as millers; nearby, the Strangemans flourished as brewers. Haughtons, Lambes, Clibborns, Pims, Allens, Jacobs, of biscuit-making fame, the Grubbs of Castle Grace, the Malcolmsons, Millers of Clonmel – each family found its niche in the new country.

Eventually the old saw about Philadelphia Quakers – that they came to do good, and did well – was to apply to Irish Quaker families. but this was still far from being the case when Admiral Penn, William’s father, first set foot on Irish soil in the mid-1600s. Quakers were still very much second-class citizens, protesters, and troublemakers. The Admiral’s family, on the other hand, were staunch Church of England gentry who had been granted land in the Irish “colony” by Cromwell.

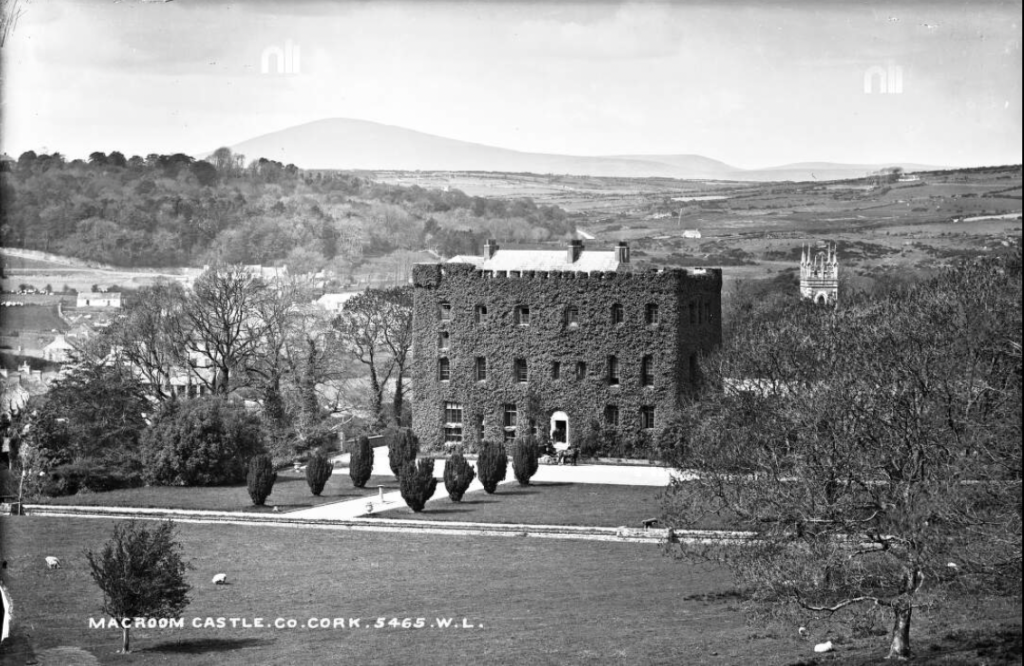

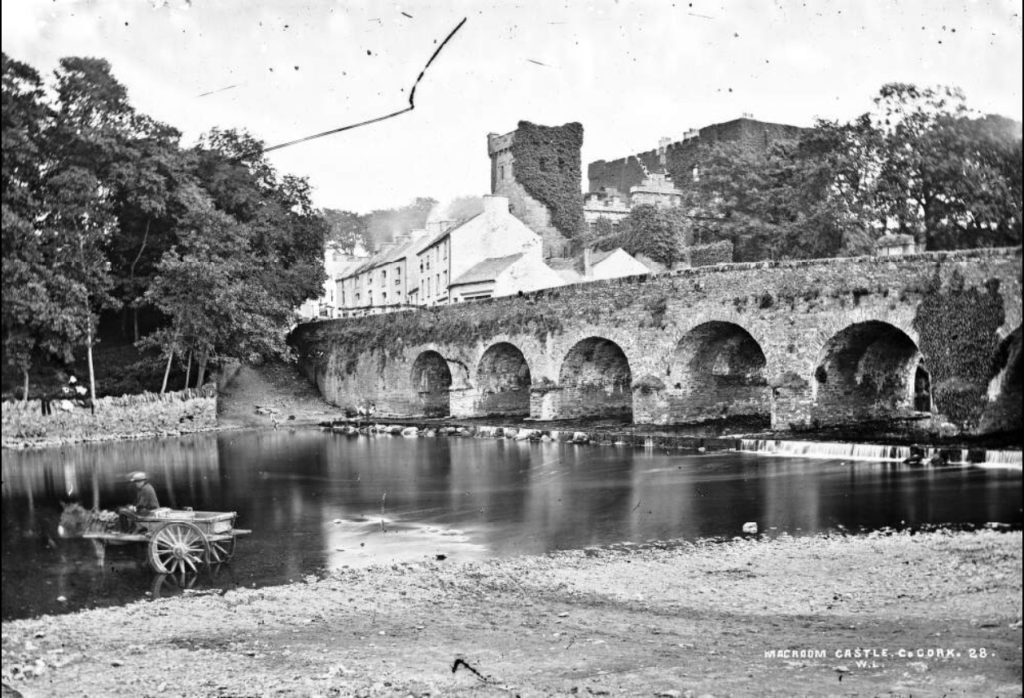

The Irish chapter of Penn’s family history begins in Macroom, a pretty market town on the way to Cork, less than a day’s drive from Shannon. When the Admiral’s wife’s property near Shannon had been forfeited, the Penns were granted Macroom Castle and the surrounding grounds in compensation. In 1655, after Admiral Penn had fallen into disfavor with the English government, he retired to Macroom with his family. Young William Penn was 12 when, in the following year, the Quaker Thomas Loe (founder of the Society of Friends), who, as legend has it, came to the castle at the Admiral’s invitation. This itinerant preacher from Oxford was eventually to change William Penn’s life.

History is embedded in Macroom: there are few historic markers on buildings and it takes a bit of inquiry to verify what you’re looking at. For example, what seems like the sort of tower commonly found at the center of a typical Irish crossroad turns out to be, in Macroom, an imposing remnant of the Penn Castle itself. Our antiquated guidebook indicated that the building in which the Penns had lived was bordered on one side by the River Sullane, with windows looking out onto a rugged stretch of land ending at the foothills of a mountain range. Yet the structure before our eyes was smack in the heart of the town, so central that traffic must be routed around its hulk. Moreover, it is commonly referred to as “The Castle.”

The confusion was cleared up for us by a retired schoolteacher named John Ahern, the town’s unofficial historian. Referred by the Town Clerk, we knocked at Ahern’s door just as he was about to set out for a walk. But when he learned our purpose, he doffed his raincoat and led us back into his study. There he switched the electric fire on again and took down a book of local history already marked on the pages covering the Penn family. He told us that the classic 15th-century keep at Macroom center is all that remains of the original castle, the rest of the structure having been torn down in 1967 to make way for a technical school. Ahern’s book, predating this modern development, showed the entire castle – a square, three-story fortress sporting turrets and a stem facade. In Macroom, it seemed, we were too late for all but the remnants of Penn history.

We were not disappointed for long, however. As it happened, Mr. Ahern had in his pocket the keys to the town museum, and he further postponed his constitutional in order to take us there. Housed in a modest building on Castle Street adjacent to the keep, the museum announces itself in large letters painted on its bright yellow walls. The hours are 2 to 4 p.m. daily Admission is 50 pence and a bargain: inside, the visitor shares in the story of Irish small-town life as only a simple community institution can present it. There are cooking and farming implements from the last century, costumes, games, and records of sporting life, as well as photographs and mementos of the Penn Castle before it was demolished. This was not the only time that our pursuit of William Penn led down an intriguing byway, nor was it the last to occasion a Quakerly quaffing of spirits; to thank Mr. Ahern for his trouble we went across the street for a pint at Quinlan’s Pub, and were told that it, too, is an ancient fixture in Macroom, and therefore a “must” for visitors.

Photo: © The Lawrence Photograph Collection / National Library of Ireland

Although the area around Macroom offers great country for casual wandering – and for golfing and fishing if your enthusiasms are more specific – we headed straight down route V22 to the city of Cork.

It was in Cork that William Penn met Thomas Loe for a second time. He went to hear him speak, and was so moved by the man’s eloquence that he became a Quaker on the spot. This was an act for which Penn suffered immediate consequences.

The year was 1667. The Penns, forced to give up Macroom Castle, had been granted even larger estates in the Barony of Imokilly, south of Cork. The family was in England; young William had been sent over to Ireland by his father to see to the new holdings. After his conversion, Penn was attending a meeting of the Cork Society of Friends, and there, on September 3, he and 18 others were taken prisoner on the grounds of a proclamation of 1661 which prohibited the assemblies of Anabaptists, Quakers and Fifth Monarchy Men.

Penn’s petition to Lord Orrery, the President of Munster, against the proclamation, which he called a “dead and antiquated relic,” was the first plea for religious freedom from the man who was the become its greatest champion. The petition was successful and William was released. However, Lord Orrery happened to be a friend of the Admiral, and when news of William’s imprisonment in Cork reached his father, William was angrily recalled to England. As a footnote to this episode, it turned out that William sailed back with English Quaker Josiah Coale, who had been to America and succeeded in stirring up the newly-converted William’s interest in the New World as a possible Quaker asylum.

Cork thus remains the place where everything began for William Penn: conversion, prison, and commitment to freedom of worship. The successor to the meeting house where Penn and his fellow Friends were probably rounded up and marched off to jail still exists. It stands on a main thoroughfare, Gratton Street, but is indistinguishable from the surrounding buildings except by its yellow facade, newly refurbished. Today, it houses a social-service organization and, characteristically, bears no plaque indicating its past.

Much easier to find is the new meeting house on Summerhill South. This is an undistinguished building marked – happily – with a bronze sign set into its red brick wall which reads: “This meeting house was built in 1938 on leaving our premises on Gratton Street, which Friends occupied from 1677 to 1938.” The easiest way to see it is to attend a meeting for worship. Inside, the utilitarian structure is transformed into a cozy library room set round with benches taken from the Gratton Street meeting. Chairs are arranged in a semi-circle around a table bearing a vase of flowers and a Bible in exactly the spirit of simplicity that William Penn would have approved.

Photo via Ballymaloe Foods

But the hidden glory of this quiet little enclave in Cork is to be discovered on the hill behind the meeting house. What looks at first like an enchanting secret garden lined with magnificent holly trees opens out into an ancient burial ground with a fine view over the city. It is one of those rare and unexpected spots in which a special quality has survived through generations. Cut into the cemetery stone wall is the legend: “This burying place was first purchased by Friends of Cork Anno 1668 and rebuilt and enlarged Anno 1720. Above re-cut 1949.” (Meetings are held on Sunday at 11:00 a.m. To visit the meeting house and graveyard at any other time you will need to contact the pleasant caretaker, Mrs. Somerville, around the corner at 50 Quaker Road.)

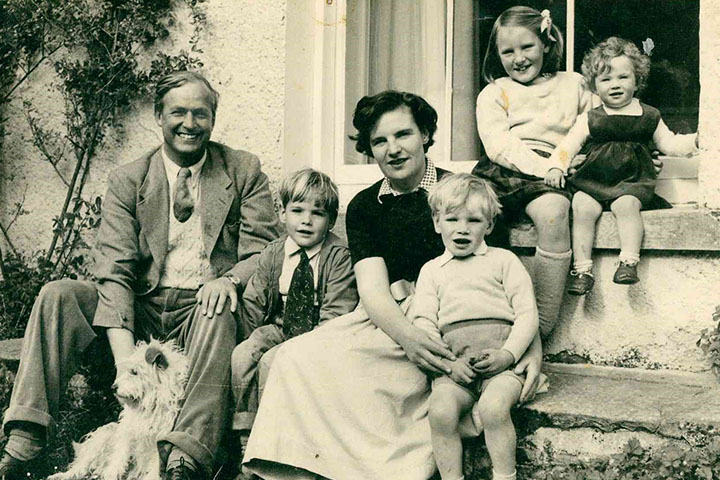

There is much to see and do in the bustling center of Cork. We descended for tea and a look around the majestic Crawford Municipal Art Gallery on Emmet Place, which contains a good cross-section of work by Irish painters, including work by Jack B. Yeats, the poet’s brother. Superb light dinners are served at the gallery’s cafe on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday evenings beginning at 6:30. The imaginative menus are masterminded by Myrtle Allen, the gifted chef of Ballymaloe House, forty minutes south of Cork, which we would make our headquarters for the Shanagarry leg of our William Penn tour.

Part of the Allen family’s enterprising cluster of restaurants and cookery courses, the Crawford Gallery Cafe is managed by Fern, the youngest Allen, who trucks in the famous bread and fresh garden produce daily from the farm in Ballymaloe. She has added some nice touches including candlelight and, often, a classical guitarist. Fern told us that the architect who grouped the Gallery’s old red-brick structure with new extensions of his own design was her great-grandfather, Arthur Hill. A wood model of the completed gallery, which was opened in 1885, stands on the landing at Ballymaloe House.

We started the next morning for Shanagarry, the last Irish home of the Penn family. It was here in this tiny village on the east coast of Cork that William Penn’s diary of his 1669 visit was found by a Quaker schoolmaster in the early years of this century. Published for the first time in 1916, it recounts,

“27 10th Month…I came into Imokilly to my father’s house, Shanagarry or old Garden…”

The spot is full of legends carefully cultivated by the inhabitants. There are rumors of magic wells which cure ague; of saints who raised towers overnight; there is even the tradition that Jesus sought refuge against his persecutors in Shanagarry.

But William, whether mindful of local folklore or not, had business to do. By now the Admiral had received a knighthood and his name carried considerable weight in the district. His grant comprised of Shanagarry Castle and some 7,000 acres reaching down to Ballycotton Bay at the very edge of the coast. In addition, he had been given the Governorship of Kinsale, a thriving port and market town to the west. Altogether, his new post and revenue from his estates netted the Admiral an annual income of about 2,000 pounds – a tidy fortune in those days. William’s job was to lease various parcels of the land and to collect the rents from tenants. Having accomplished those tasks by the end of 1669, William turned to what he now viewed as his real vocation, a ministerial journey south of Cork to visit Friends in Bandon, Skibbereen, Baltimore, and Rosscarbery, making a stop at Kinsale to oversee his family’s holdings there.

Photo: National Inventory of Architectural Heritage Ireland

Shanagarry, however, remained Penn’s base of operations. Today the town and surrounding countryside are almost exactly as they were in his time: low-lying emerald-green fields dotted with grazing sheep, boundless farmlands, windswept skies and the smell of the sea nearby. Shanagarry itself consists of a general store, a pub run by Margaret and Maurice Walsh, a tiny municipal park opened three years ago by the local priest, Fr. Bertie Troy, and, adjacent to it, picturesque ruins of the Penn Castle. Not far away, behind a row of modern bungalows, sit the remains of Sunville House, where William Penn’s grandson William lived until his death in 1746.

Ivan Allen, the scion of the Quaker clan, which owns and operates Ballymaloe House nearby, blames himself for not having rescued Sunville from near oblivion.

“It was a charming place,” he muses, his long legs crossed in front of a peat fire in one of Ballymaloe’s spacious drawing rooms.

“But we have one compensation: I had the presence of mind to remove the stone fireplace that you see in front of you from Sunville, before it fell into ruins. And in a way,” Allen continues, “it’s quite as much at home here because, you see, Penn visited this house often, along with Bishop Berkeley of Cloyne, two miles down the road.”

Did he mean the theologian and philosopher, George Berkeley?

“I do.” Allen confirms simply.

His wife, Myrtle Allen, chef extraordinaire, joins our discussion of Irish Quakers. “Have you heard of the Annals of Ballitore?” she asks. I had not.

“Stop there on your way back to Dublin,” she said mysteriously. “Get someone to show you the library.”

One of the delights of journeying with a purpose is being able to follow up on leads which begin casually in conversation: “Have you been to…?” “Do you know about..?” When we reluctantly left the remote setting of Shanagarry for the road north, we already had plans to stop along the way at Clonmel, to track down another Quaker graveyard. But on the strength of Myrtle Allen’s intriguing hint, we decided to pay Ballitore a visit as well. Still another suggestion had emerged from a chat with a Ballymaloe guest who had alerted us to the legend of Major Grubb, who, in 1926, was buried standing upright, gun in hand, in an unmarked cairn facing the Knockmealdown Mountains.

As it worked out, these three suggestions traced our route for us in perfect logical order. We took routes N8 and 72 from Cork through the high pass known as the “Vee.” There, a few miles from Clogheen, was the major’s monument, just a pile of rocks to the casual observer, but a unique shrine to those who know about this odd military descendant of one of Ireland’s Quaker children.

In Clonmel, our gumshoe efforts were rewarded by the discovery of a large Quaker burial ground right in the center of the town, yet well hidden down a cul-de-sac alongside Ann Street and perpendicular to O’Neill. An almost invisible plaque set into the high stone wall identifies the site. A glimpse past the iron gate, now chained and padlocked, reveals a sylvan garden in total disarray – a walled crypt disturbingly set off from the rest of town in a manner of the tiny Jewish cemetery in New York’s Greenwich Village. Not quite hermetically sealed away from the prosperous modern bustle of Clonmel, this “haunt” is nonetheless an acute reminder of a time when Quakers were a feared minority.

Ballitore was not to be found in our guidebook map. It is a tiny village nestled in the upper valley of the River Griese, near the town of Athy, from which signs will direct you. (We took N24 and N76 from Clonmel to Kilkenny, then N78 to Athy.) Not having had the foresight to request specific road directions, we almost gave up on Ballitore. In the end, we were relieved that we had not abandoned the quest, for Ballitore exists in a time warp which is almost unimaginable to the casual visitor. For example, the most recent postcard, which the grocer’s wife managed to produce from her dusty drawer, pictures the village’s main street in black-and-white, ornamented with a scattering of automobiles dating from the ’40s. And yet an enterprising local Quaker has renovated the meeting house and converted it into a handsome museum displaying Ballitore history as revealed in correspondence and records.

Photo: ©4.0 Ridiculopathy via Wiki Commons

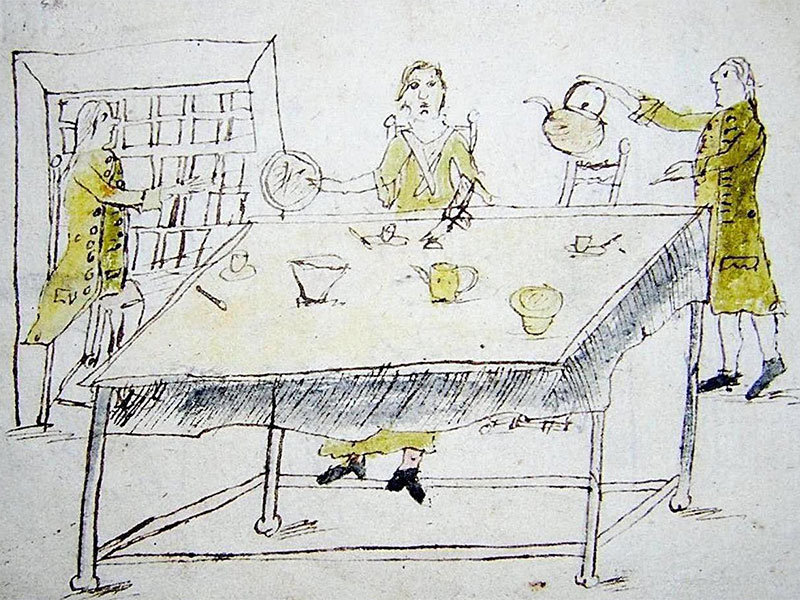

Ballitore was settled in the early 18th century by the Quakers John Barcroft and Abel Strettel. In 1707, a meeting house was built, and in 1726 Abraham Shackleton (an ancestor of Ernest Shackleton the Antarctic explorer) opened a small boarding school, which was later attended by the philosopher and parliamentarian Edmund Burke. But it is in the library next to the museum that the real treasures are on view and we offered

silent thanks to Mrs. Allen for having alerted us to its contents. There, next to a Quaker wedding dress (suitably grey), a man’s costume and an assortment of hats and walking sticks, is the original edition of the Annals of Ballitore. Penned by Mary Leadbeater, a local lady of learning, these journals cover the years 1766 to 1824. They form a unique and detailed record of Quaker life in a small Irish village, and are delightful reading.

In a case nearby is a collection of Burke’s letters, one of which, addressed in 1844 to Richard Shackleton, who took over the school’s headmastership, begins “Dear Dicky.” That Quakers early had a sense of their place in Irish history is evidenced by an enormous manuscript whose title begins “A History of the Rise and Progress of the People Called Quakers in Ireland from the Year 1653 to 1700….” and continues ponderously for another fourteen lines.

We ended our Quaker journey in Dublin, appropriately enough at Swanbrook House, the handsome Victorian building on Morehampton Road which serves as the center for the Society of Friends in Ireland. The library contains many Quaker family archives and may be visited from 11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. on Thursdays. The librarian directed us to the large 1692 meeting house at 4 Eustace Street, where meetings for worship are held at 11:00 a.m. every Sunday and at 10:30 on Thursday mornings.

A tour of Irish Quakerdom, past and present, leaves one with the sense that to these adventurous exiles, all things were possible. Here Quakers foxhunted, prospered as millers and biscuit manufacturers, carried rifles, brewed beer and sailed across the Atlantic to found Pennsylvania – all of which suggests that, in the rich soil of Ireland, they did both good and well.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the February 1989 issue of Irish America.

I have traced my ancestors back to a John Everard ,born 1646 ( he married a Margaret ) John became a Quaker minister in his 20 s and was supposed to be a “good” friend of William Penn .I have read that John went with Penn to visit his estate in Ireland and I believe there is a letter giving “a” John Everard a parcel of land in Pennsylvania…but I can find very little evidence of his trip Ireland…any help or suggestions Greatly appreciated