The Irish Famine was the first national disaster to attract international fundraising activities. These activities cut across traditional divides of religion, nationality, class and gender. Such a response was unprecedented.

The earliest fund-raising activities took place at the end of 1845. The first place to send money to Ireland was Calcutta in India. The fundraising was initiated by British citizens residing there who believed that their actions would show the Irish people the benefits of being part of the British Empire.

The Committee, which was headed by Sir Lawrence Peel, an English judge, and Sir James Grant, an English Civil Servant, demonstrated that fund-raising activities were not confined to people of Irish extraction. However, a number of Irish men and native Indians were also active in the administration of the Committee.

The Committee appealed to other Europeans residing in India and to the ‘native community’ to become involved in their philanthropic activities. Moreover, a direct appeal was made to Sir Hugh Gough, a high-ranking soldier in the British Army who was Irish-born, to give his support to the Committee. At this stage, over forty per cent of the British army serving in India were Irish-born and so they were regarded as a valuable source of funds. And indeed, they gave generously. Indians also gave liberally, donations coming from wealthy Hindus and a number of Indian princes, but also from those who were less well off, including sepoys in the army, and from many low-skilled and low-paid Indian servants. Within a few months, the Calcutta Committee had raised £14,000 for the relief of the Irish poor. To oversee the distribution of this money, a team was assembled in Dublin, headed by the Anglican Archbishop, Richard Whately. Most of the money received from India was sent to Connaught in the west of Ireland, some of it being channeled through the local Catholic priests.

Just as relief efforts were getting underway in India, a committee was established in Boston in the United States. In America, perhaps inevitably, famine relief became tied up with demands for Irish political independence, with the committee being formed at the initiative of the local Repeal Association (followers of Daniel O’Connell). Predictably, the food shortages were cited as the most recent example of British misrule and of the failure of the British Empire. At a meeting in early December 1845, at which $750 was raised for the Irish poor, one speaker claimed that, due to ‘the fatal connection of Ireland with England, the rich grain harvests of the former country are carried off to pay an absentee government and absentee landlords’. These fund-raising efforts were short-lived, however, drying up at the beginning of 1846, when it was suspected that reports of the distress had been exaggerated.

The Irish Government designated the 17 May 2009 as the first National Famine Memorial Day. On that day, Irish people throughout the world remembered and honoured the victims of Ireland’s Great Hunger – which to this day remains one of the most lethal famines of the modern era.

The vast majority of those who died or emigrated remain both nameless and invisible. Their lives – and deaths – were so unimportant that their departure from Ireland or their passing away was not recorded or counted. Moreover, many famine victims died without any burial rites and their bodies remained coffinless and unmarked, even by a simple headstone. Out of population of eight-and-a-half million prior to the Famine, over one million people died, approximately two million people emigrated, and each of those deaths and departures represented whole families torn apart by the loss of a loved one or loved ones.

The impact of the famine years is all the more tragic because the catastrophe unfolded at the centre of the richest and largest empire in the world. Moreover, since 1800 Ireland had (reluctantly) been part of the United Kingdom and so was governed directly by London. But the British government chose not to use the resources of that vast empire to prevent suffering and starvation, literally on its doorstep. Appeals for relief fell on deaf ears and arguments were marshalled to justify the lack of intervention — Ireland was over-populated, the country needed to modernize, the famine was God’s way of punishing the Irish people for their laziness, their dependence on potatoes, their religion. In the face of the inadequacy and parsimony of government relief, the role of private relief became increasingly important and this evening I would like to talk about the role of private charity in giving assistance to, and saving the lives of, the Irish poor.

One of the remarkable features of the Irish famine was that it was the first national disaster to attract international fundraising activities. These activities cut across traditional divides of religion, nationality, class and gender. Such a response was unprecedented. The first fund-raising activities occurred in 1845, following the initial appearance of the potato blight, but most of them took place in the wake of the second, and far more devastating, failure of the potato crop in 1846. Outside intervention was short-lived, and by 1848, most of the donations had dried up. Sadly, the famine was far from over, with more people dying in 1849 than in ‘Black ‘47’.

(Courtesy of Quinnipiac University / Hartford Courant File Photo)

These two examples of donations to Ireland illustrate the diversity of motivations for intervening. At this stage, in spring 1846, nobody suspected that any further interventions would be necessary. Although there had been potato failures in Ireland before, and consequent food shortages, they had never lasted for more than one year and in 1846 there was an expectation that the blight had run its course. This, sadly, was not the case. In summer 1846, the blight reappeared in Ireland even more virulently than in the previous year. And it appeared earlier in the harvest period. The impact was devastating and immediate. As early as October, deaths from hunger and famine-related diseases were being reported.

Despite the shortages being more severe and widespread, the British government decided not to interfere in the market place to provide food to the poor Irish, but they left food import and distribution to free market forces. Moreover, they allowed foodstuffs –vast amounts of foodstuffs – to be exported from Ireland. Merchants made large profits, while people starved. At the same time, public works, which entailed hard physical labour building roads that led nowhere and walls that surrounded nothing – were made the primary form of relief. By the end of 1846, deaths from hunger, exhaustion and famine related diseases were commonplace. The Famine had commenced – and no part of the country, from Belfast to Skibbereen, had escaped.

It was in the midst of this unfolding catastrophe that private relief efforts commenced on behalf of the Irish poor.

By the end of 1846, news of the second potato failure and of the suffering of the Irish people was being reported in newspapers throughout the world. The response was immediate and compassionate. A number of fund-raising committees were established in both Ireland and Britain. One of the most successful and well- respected was the Central Relief Committee of the Society of Friends, which was established in Dublin in November 1846, at the suggestion of Joseph Bewley (a tea and coffee merchant – Bewley’s cafes) Though the Irish Quakers were small in number (c. 3,000), they were very successful in raising money outside Ireland. These funds played an important role in providing relief, particularly through the establishment of soup kitchens. By the end of 1847, when their funds dried up, the Quakers had distributed approximately £200,000 worth of relief throughout Ireland.

Quakers themselves were personally involved in dispensing this relief, which took its toll. At least 15 Quakers died as a result of famine- related diseases or from exhaustion. This included Joseph Bewley. Undoubtedly though, their hard work had saved thousands of lives. The involvement of the Quakers was particularly important because it was direct, was provided in the communities where it was most needed, and it was given without any religious or other stipulations.

An even larger relief organization was the British Relief Association. It was formed in January 1847 by Lionel de Rothschild, a Jewish banker in London. Again, its fund-raising activities were international, with donations being received from locations as diverse as Venezuela, Australia, South Africa, Mexico, Russia and Italy. In total, over 15,000 individual contributions were sent to the Association, and approximately £400,000 was raised. This money was entrusted to a Polish Count, Paul de Strzelecki, a renowned scientist and explorer. He travelled to Counties Mayo and Sligo in 1847, where he established schools at which free food was given to the local children. Despite falling victim to ‘famine fever’, he survived and remained working with the poor in Ireland. In August 1848, when the Association’s funds had run out, the schools were closed, despite promises from the Prime Minister that they would be supported. Strzelecki refused to accept any money for his work, but he was knighted by the British government in 1848. Ironically, the only other person to be knighted for his work during the Famine was Charles Trevelyan, Permanent Secretary at the Treasury, who was renowned for his parsimonious approach to relief.

Unfortunately, the involvement of relief organisations has been tainted by the memory of proselytism or, as it is known in Ireland, souperism, that is, giving relief to the Catholic poor in return for their conversion to Protestantism. Proselytism was not new in Ireland, but its use during this period of suffering seems particularly reprehensible. However, although it is generally associated with the main Protestant churches in Ireland (the Anglican and the Presbyterian) in reality it was only carried by a minority of evangelicals, who genuinely believed that they were saving souls, not merely lives, by their actions. Money was raised in Protestant churches in Britain, Dublin and Belfast for this purpose.

A well known missionary was Michael Brannigan, a convert from Catholicism to Presbyterianism, and a fluent Irish speaker. In 1847 he established 12 schools in Counties Mayo and Sligo. Attendance dropped when the British Relief Association began providing each child with a half-pound of corn-meal every day, but this ended in August 1848 when their funds ran out. Consequently, by the end of 1848 the number of ‘Bible schools’ had grown to 28, despite ‘priestly opposition’.

The worries of the Catholic Church were articulated by Fr William Flannelly of Galway, in a letter to Daniel Murray, Archbishop of Dublin, in April 1849. He wrote:

‘It cannot be wondered if a starving people would be perverted in shoals, especially as they [the missionaries] go from cabin to cabin, and when they find the inmates naked and starved to death, they proffer food, money and raiment, on the express condition of becoming members of their [churches] conventicles.’

The Freeman’s Journal condemned souperism as ‘nefarious unchristian wickedness’. The Pope even felt worried enough to urge the Catholic hierarchy in Ireland to oppose the work of missionaries and, on one occasion, he reprimanded the bishops for not doing enough to protect their flocks.

By 1851 the main missions claimed that they had won 35,000 converts and they were determined to win more. Shortly afterwards, 100 additional preachers were sent to Ireland by the British Protestant Alliance to missionary settlements in destitute areas, such as Dingle and Achill Island. Ultimately, the impact of the missions was slight and tended to be localised, but many converts had to move elsewhere due to hostility and contempt in their own communities. Moreover, the memory of souperism, and ‘taking the soup’, has been a long and bitter one in parts of Ireland.

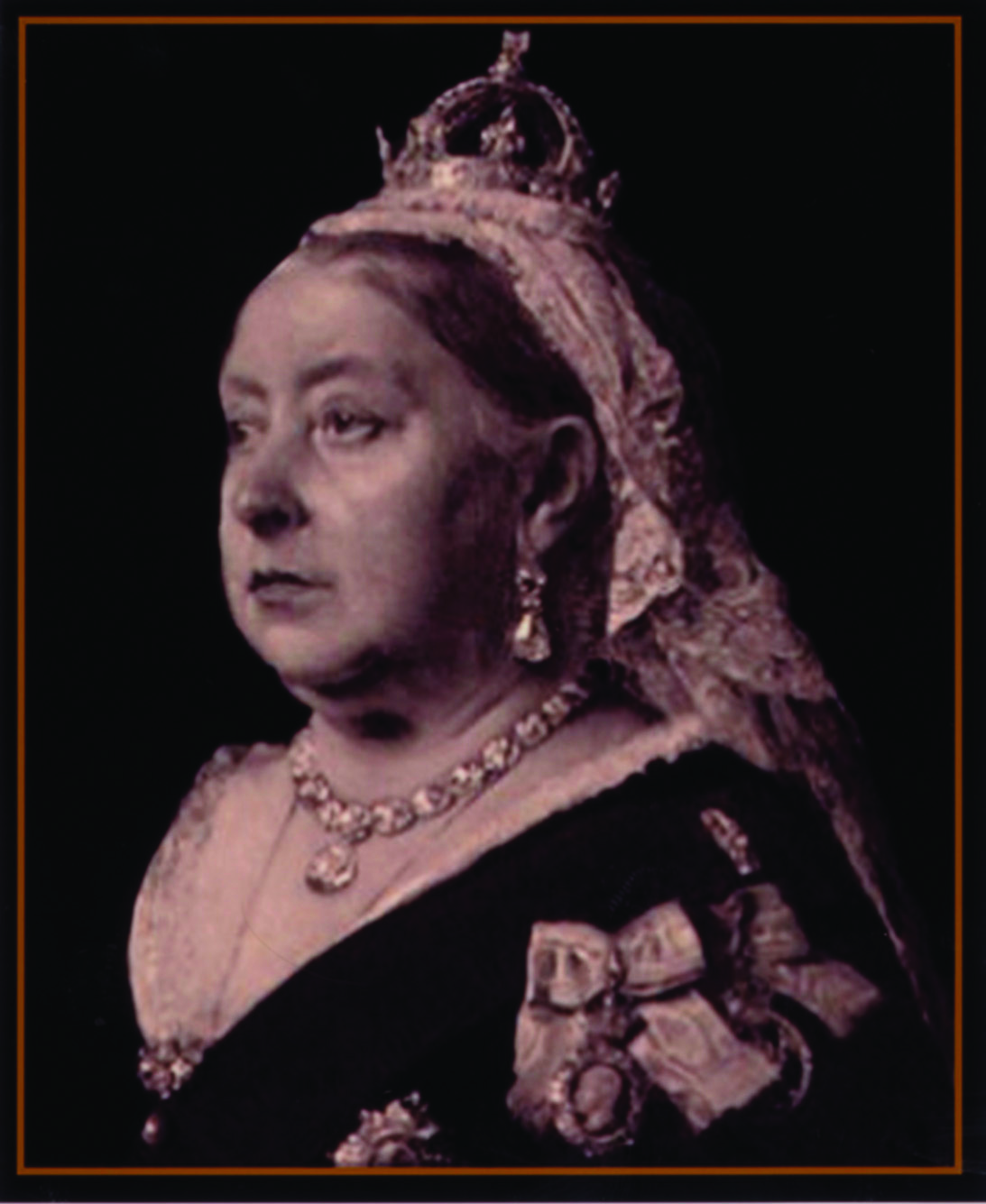

Some of the donations made by individuals to famine relief also proved to be controversial. In popular memory, Queen Victoria is remembered as ‘The Famine Queen’, for allegedly only giving £5 to help the starving Irish. In reality, she donated £2,000 to the British Relief Association in January 1847. This made the Queen the largest single donor to famine relief. She also published two letters, appealing to Protestants in England to send money to Ireland. Her involvement was widely criticised at the time, notably by the influential newspaper, the London Times, which argued that giving money to Ireland would have the same effect as throwing money into an Irish bog.

During her sixty-three-year-long reign, Queen Victoria only visited Ireland four times. The first time was in 1849 when she commented on the beauty of Irish women and the rags worn by them. The latter she attributed to the fact ‘they never mend anything’. Queen Victoria’s final visit to Ireland was made in April 1900, when she was aged 82, almost blind and wheelchair-ridden. Although she was generally welcomed, some nationalists protested, including Maud Gonne and James Connolly. Gonne wrote an article criticising Queen Victoria for her indifference to the poor during the Famine, which said:

“And in truth, for Victoria, in the decrepitude of her eighty-one years, to have decided after an absence of half-a-century to revisit the country she hates and whose inhabitants are the victims of the criminal policy of her reign, the survivors of sixty years of organised famine, the political necessity must have been terribly strong; for after all she is a woman, and however vile and selfish and pitiless her soul may be, she must sometimes tremble as death approaches when she thinks of the countless Irish mothers who, sheltering under the cloudy Irish sky, watching their starving little ones, have cursed her before they died.”

The journal was banned by the British authorities and all copies seized. The name of the article was ‘The Famine Queen’ and this appellation has remained in usage. The belief that Queen Victoria only gave five pounds to help the starving Irish has also proved to be enduring.

Another head of state to send money to Ireland was the Sultan of Turkey. He had an Irish doctor but he was also trying to create an alliance with British government. He initially offered £10,000 but the British Consul in Istanbul told him that it would offend royal protocol to send more money than the British Queen. As a result of this diplomatic intervention, Abdulmecid reduced his donation to £1,000. Nonetheless, his generous contribution was gratefully received by people in Ireland, with a formal letter of thanks being sent by “noblemen, gentlemen, and inhabitants of Ireland,” According to local legend, Abdulmecid tried to compensate for his reduced monetary donation by sending two ships to Ireland, laden with food. Allegedly, but there is no documentary proof of this, the British government refused to allow the ships to dock in either Cork or Dublin so, surreptitiously, they docked in Drogheda. This story is accepted in Drogheda today. On 2 May 2007, the Turkish ambassador to Ireland was invited by the city’s Mayor, Frank Goofrey, to a ceremony to place a memorial plaque on the walls of the West Court Hotel, which, according to legend, used to be the old Government Building where the Turkish sailors and Captains had stayed. During the unveiling, the Mayor drew attention to the City’s logo, which consists of a crescent and star just like the Ottoman crescent and star. He added that the plaque would serve as the symbol of friendship between Ireland and Turkey. So an act of kindness that took place over 160 years ago, continues to have repercussions today.

Support for the Irish poor also came from the head of the Roman Catholic Church in Rome, Pope Pius IX. The involvement of a Pope in the secular affairs of another country was unusual. Nonetheless, at the beginning of 1847, Pope Pius donated 1,000 Roman crowns from his own pocket to Famine relief. In March 1847, he took the unprecedented step of issuing a papal encyclical to the international Catholic community, appealing for support for the victims of the Famine, both through prayer and contrition, by also by making financial contributions. As a result, large sums of money were raised by Catholic congregations throughout the world. Most of this aid was put in the hands of Archbishop Murray in Dublin.

Other high profile donors to Famine relief in 1847 included the tsar of Russia (Alexander 11) and the President of the United States, James Polk. The latter, who donated $50, was criticised for the smallness of his donation. Arthur Guinness, the Dublin brewing magnate, also made a number of modest contributions.

Inevitably, a large portion of relief came from the United States, not only from the Irish Catholic community, but from a wide variety of groups, including Jews, Baptists, Methodists and Shakers. At the beginning of 1847, the American Vice President, George Dallas, convened a mass meeting in Washington to raise money for Ireland. He urged that every American state should follow suit. The Washington meeting was attended by many senators, notably the young Abraham Lincoln.

During the meeting, letters were read from Ireland, including one from the women of Dunmanway in County Cork. It was addressed to the Ladies of America. It said:

“Oh that our American sisters could see the labourers on our roads, able-bodied men, scarcely clad, famishing with hunger, with despair in their once cheerful faces, staggering at their work … Oh that they could see the dead father, mother or child, lying coffinless, and hear the screams of the survivors around them, caused not by sorrow, but by the agony of hunger.”

Remarkably, even though America was at war with Mexico, Congress gave permission for two navy vessels to be used to take supplies, on behalf of the Boston Relief Committee, to Ireland and to Scotland, where the potato had also failed. The resolution authorizing the use of the ships by private individuals, even to this day, “remains unique in the history of Congress.”

On 17 March 1847, foodstuffs were loaded onto the Jamestown. It left Boston for Cork a week later, taking only 15 days and 3 hours to complete the transatlantic journey. All of the crew were volunteers. The Captain, Robert Forbes, caustically commented that as the food supplies had taken only 15 days to cross the Atlantic, they should not take a further 15 days to reach the Irish poor. His comment was apt. The labyrinth of bureaucracy attached to the public works had meant that it had taken between 6 and 8 weeks for them to be operative – far too long for a people who were starving.

Forbes declared himself to be impressed with the women of Cork – because ‘they shake hands like a man’. Although he was feted, he shied away from publicity and, significantly, refused an invitation from the authorities to travel to Dublin to receive an honour from the British government. This fantastic endeavour on behalf of the Irish poor was only diminished by the fact that on the return journey, a man was lost overboard – and he was the only Irish-born member of the crew.

These examples represent only a small portion of the assistance that was given to Ireland during the years of the Great Hunger. I would like to conclude by mentioning briefly the contributions that came from people who were themselves poor, politically marginalised, and had nothing to gain through their interventions.

Throughout 1847, subscriptions to Ireland came from some the poorest and most invisible groups in society. This included former slaves in the Caribbean, who had only achieved full freedom in 1838, when slavery was finally ended in the British Empire (Daniel O’Connell played a role in that). The British government had given the slave-owners £22 million pounds compensation for ending slavery; the slaves received nothing. Donations to Ireland included ones from Jamaica, Barbados, St Kitts, and other small islands.

Painting credit: The Granger Collection, New York via PBS

Donations were also sent from slave churches in some of the southern states of America. Children in a pauper orphanage in New York raised $2 for the Irish poor. Inmates in Sing Sing Prison, also in New York sent money, as did convicts on board a prison ship at Woolwich in London. The latter lived in brutal and inhumane conditions, and all of them were dead only twelve months later from ship fever.

A number of Native Americans, including the Choctaw tribe, also sent money to the Irish poor. The Choctaws had themselves suffered great tragedy, having been displaced from their homelands and forced to move to Oklahoma in the 1830s – the infamous Trail of Tears. They send $174 dollars to Ireland. The involvement of the Choctaw people did not go unnoticed. A newspaper in Oklahoma averred that:

“What an agreeable reflection it must give to the Christian and the philanthropist to witness this evidence of civilization and Christian spirit existing among our red neighbours. They are repaying the Christian world a consideration for bringing them out from benighted ignorance and heathen barbarism. Not only by contributing a few dollars, but by affording evidence that the labours of the Christian missionary have not been in vain.”

Although the amounts that these poor and dispossessed people sent to Ireland were relatively small, in real terms they represented an enormous sacrifice on behalf of the donors.

Towards the end of 1847, the British government announced that the Famine was over. It wasn’t. In 1848, over one million people were still dependent on relief for survival. Moreover, evictions, emigration and deaths were still rising, with proportionately more people dying in 1849 than in Black ’47. Unfortunately though, most of the private fundraising efforts had come to an end by 1848 and the Irish poor were again dependent on Irish landlords and the British government for relief.

To conclude, although the involvement of private charity was short-lived, it was vital to the survival of many Irish poor. It proved to be particularly crucial as government relief was inadequate, provided with parsimony and reluctance, and constrained by views of the Irish poor as undeserving of assistance. In contrast, most private charity honoured the dignity of the recipient. Moreover, without these generous contributions, many, many more Irish people would have died during that tragic period.

On 17 May we honoured the memory of the victims of Ireland’s Great Hunger, but perhaps, briefly, we can also honour the memory of those people – many of whom are also nameless – who gave money generously to people whom they had never met, but whose tragic circumstances had touched their hearts.

Christine Kinealy is a Professor of Irish History at Drew University. She is the author of a number of books on the Great Hunger, including This Great Calamity, The Great Irish Famine, and The Hidden Famine: Hunger, Poverty and Sectarianism in Belfast. Her latest publication, Repeal and Revolution: 1848 in Ireland, was published by Manchester University Press in July 2009.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June/July 2010 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply