A historical look at the Irish of Butte, Montana

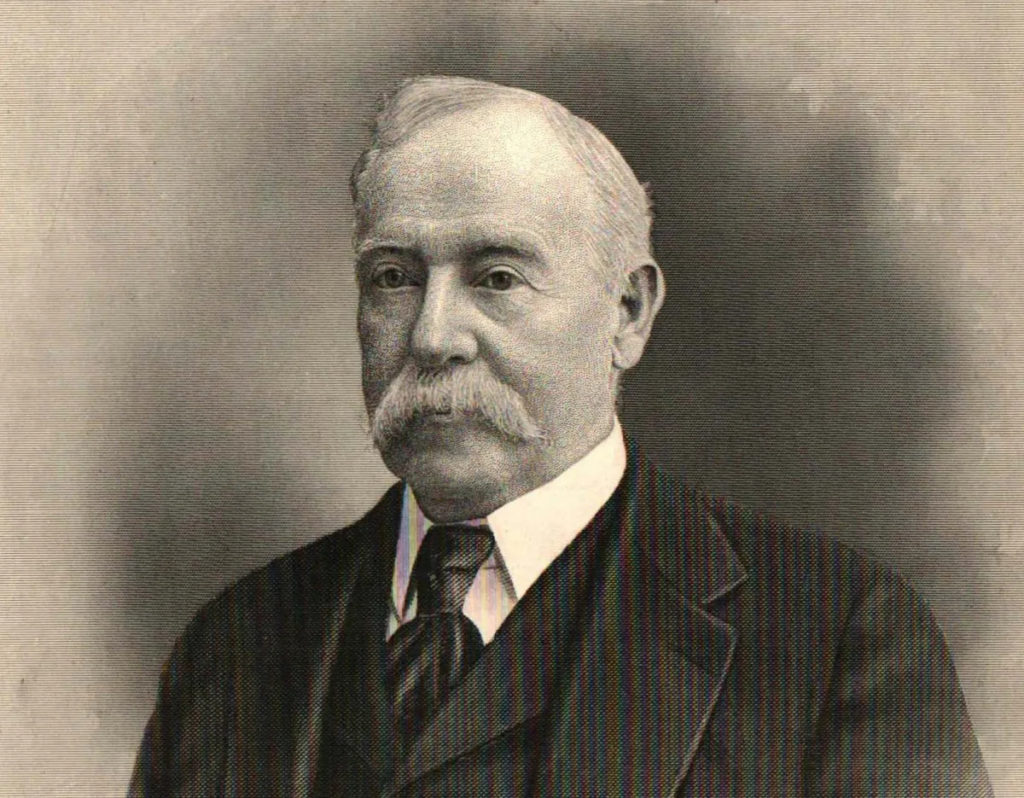

Marcus Daly, who became one of the richest men in the West, was born in 1841, in Ballyjamesduff, County Cavan, the youngest of eleven children of a farm family. At 15 he arrived in New York City with very little money and limited education. It took him five years to save enough money to buy passage to San Francisco where he had a sister. From there he headed to Nevada to work the Comstock Lode mine.

By 1871, Daly was in Ophir, Utah, working as a foreman for the Walker Brothers, a mine owning, banking syndicate in Salt Lake City. In 1872 while Daly was inspecting a mine in Ophir with a Mr. Evans and his daughter Margaret, the young lady lost her footing and tumbled into Daly’s arms. Later that year they were married. Margaret was 18 and Daly was 30. The couple’s first two children, Margaret and Mary, were born in Ophir. A son Marcus and a third daughter Harriet were born in Butte, Montana, where in 1876 the Walkers sent Daly to investigate the Alice Silver Mine.

The young Irishman not only recommended purchase, he invested $5,000 of his own savings. He later sold out his interest for $30,000 and bought the Anaconda Silver Mine which geologists thought to be nearing exhaustion. The silver soon ran out but Daly sank a shaft into an unlikely spot and struck a vein of copper 50 feet wide. At first disappointed, Daly soon realized his luck and set about buying up the mineral rights around the area.

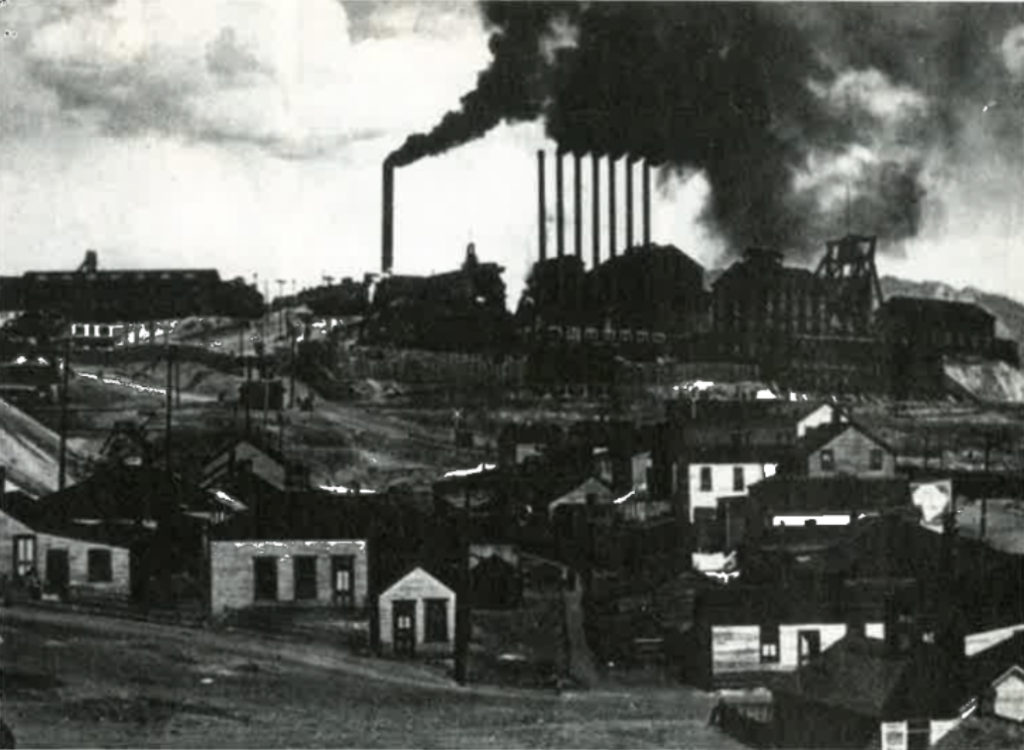

Thomas Edison had just completed the world’s first electric light power plant in New York City and copper was just coming into use for electricity and telegraph wire. Soon there was such a demand for copper that Daly built his own smelter. Previous to this the ore had been shipped to England for smelting. Soon he was rich beyond measure and was dubbed the Copper King.

Daly used his fortune to make vast improvements around Butte. He built power plants and irrigation stations, railroads and lumber mills. He built a town and one of the world’s tallest ore smelters and named them after his mine, Anaconda, which was also known as the “Never Sweat” mine because of its good ventilation. (Tourists can stay in the Marcus Daly Hotel in Anaconda today). Daly also built a beautiful mansion on 22,000 acres of land in the Bitterroot Valley across the mountains and away from the industrial chaos in Butte. The 24,213-square-foot mansion boasts 24 bedrooms, 15 bathrooms and 7 fireplaces.

Daly raised thoroughbred horses. He also dabbled in politics. A strong Democrat, he contributed heavily to the 1896 campaign of Populist William Jennings Bryan while simultaneously trying to quash the political aspirations of his rival in the copper mines William Andrews Clark, who was married to his wife’s sister.

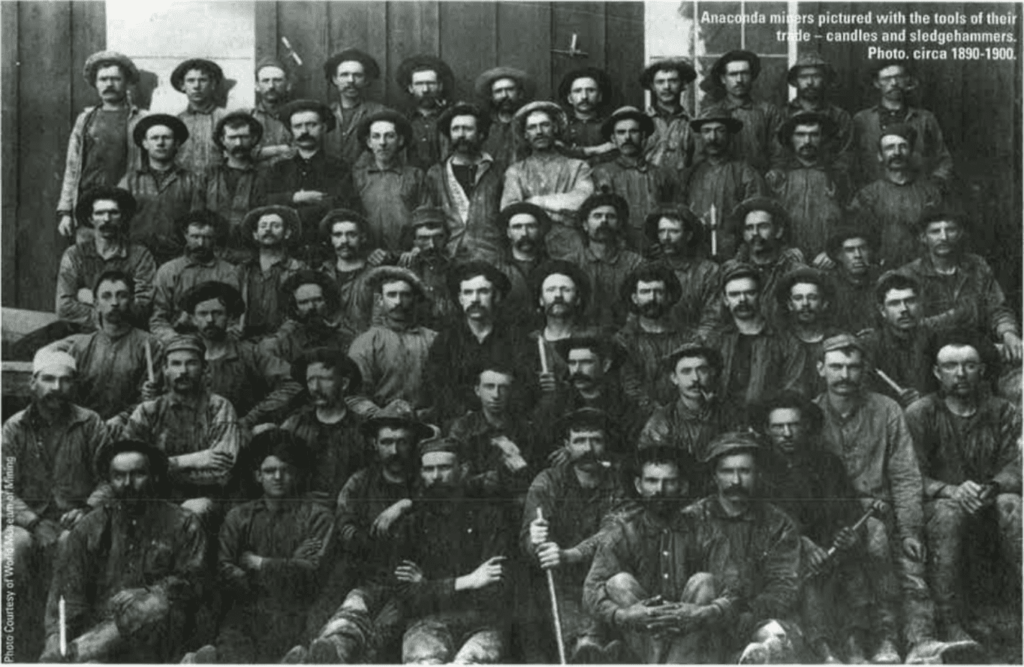

Word of Daly’s fame and fortune drew other Irish to Montana. Despite the bitterly cold winters and the remoteness of the location, Butte presented a rare opportunity — a place to start anew where work could be found and at high wages, too. Daly paid $3.50 a day, almost twice what industrial workers made in other parts of the country.

Photos ca. 1890-1900

The Irish were joined by other immigrants drawn by the promise of work, but even as others arrived the Irish dominated the town. One story describes how an Arab rug merchant named Mohammed Akara legally changed his last name to Murphy “for business reasons.”

Most of Butte’s Irish were from County Cork but large numbers also came from Counties Mayo and Donegal. They shaped the city, settling in strong communities called Corktown and Dublin Gulch, close to the mines on the Hill. Gaelic was commonly heard on the streets and understood by most who heard it.

According to David Emmons’ book The Butte Irish, by 1900 Butte had 12,000 residents of Irish descent in a population of 47,635. A quarter of the population was Irish, a higher percentage than in any other American city at the turn of the century, including Boston. Of 1,700 people who left the parish of Eyeries in County Cork between 1870 and 1915, 1,138 ended up in Butte. Members of 77 different Sullivan families left Castletownbem in Cork for Butte, which explains why in 1908 there were 1,200 Sullivans there. Butte was so Irish that de Valera stopped there twice on fundraising tours.

If Irish miners dug the ore below ground, they were also well represented at the top of Butte society. Cornelius “Con” Kelley, the son of Marcus Daly’s lifelong friend Jeremiah Kelley, became a brilliant lawyer who eventually rose to lead the Anaconda Company through labor unrest, strikes, slumps in copper prices, the Great Depression and two world wars until he retired in 1955. Of him a biographer wrote, “He made Anaconda an industrial Gibraltar around which the business storms that dismayed others played in vain.”

William McDowell came to Butte to manage the general office of the Anaconda Company for Marcus Daly and became successful in state politics serving twice as the Speaker of the House and two terms as lieutenant governor. In 1934 he was appointed the U.S. Ambassador to the. Republic of Ireland. He died in Dublin within a month of taking his post there.

Jeremiah J. Lynch was a district court judge with the more important role of leader of the Irish community in Butte. Born in Ballycrovane in County Cork, he came to Butte and worked a short while in the mines and then as a bartender. He was elected as judge in the state district court in 1906 and he often used his chambers to host committee meetings of various Irish associations of which he was a leading member. These included the Ancient Order of Hibernians, the Robert Emmett Literary Association, the Irish National Alliance, the Gaelic Athletic Association, the Hibernian Rifles, the Friends of Irish Freedom, and the American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic. He was a co-founder of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, a fraternal organization that endures in Butte today.

In fact, from the 1880s on, the Irish were represented in every level of Butte’ s society. They worked as miners and shift bosses, boilermakers and hoist engineers, but they also filled the ranks of judges, doctors, priests, firemen, policemen, lawyers, newspaper reporters and editors. From muckers in the mines to mayors and millionaires, they often belonged to the same Irish fraternal associations that allowed them to mingle freely.

These associations and the Catholic Church along with strong family ties were the keys to the building of an enduring community in what was ostensibly a boom camp.

Butte once boasted seven Irish parishes and has supplied the faith with more than its share of priests and nuns from the city’s youth. That most of the miners were Irish and Catholic is testified to by the fact that waste rock was commonly referred to in the mines as “Protestant ore.”

More than one hundred years later, the Irish still dominate this modern city of just under 35,000. A glance in the local telephone directory reveals about 100 Sullivan families alone, 43 listings for Sheas, and 32 O’Neills.

Children learn step dancing at the Knights of Columbus Hall and show off their skills in parades and performances accompanied by local Irish musicians.

Three of these musicians — Tom Powers, Mick Cavanaugh and Kevin McGreevy — make up the acoustical trio Dublin Gulch. Tom Powers organized the group to encourage others to learn about their own Irish heritage.

“I want others to learn Irish history through its music as I did,” said Powers. “If we have been successful, it is because we as purveyors of the information are adequate to the task. The body of Irish music is very entertaining; it is a good story and it’s fun to do.” They play in the bars on St. Patrick’s Day where the crowds are packed so tight they can barely dance. Later, the trio perform at a local hotel to allow young and old to listen and dance.

They are joined there by John “The Yank” Harrington and his button accordion. At 96 years of age, The Yank has just released his first CD of tunes culled from the hundreds of traditional Irish songs he learned in Ireland and Butte and in between.

He is a quiet man who prefers to speak through the instrument that seems to be an extension of his hands when he plays. The Yank has played the squeezebox for more than 80 years and his fingers still deftly ply the buttons on his accordion. He clearly remembers the snowy November day in 1911 he arrived in Butte as an eight-year-old with his parents. In a soft voice he recalls, “There were cobblestones on the street and red bricks and no automobiles.”

“Butte was a really Irish town when I first came here,” said Harrington. “As a boy I remember listening to Irish tunes at shindigs, as they called them in the boardinghouses.

Like many miners, Harrington’s father died young, in 1916, and his mother died in 1918. A year later, the young orphan was shipped east to Montreal to catch a ship for Ireland where he lived with his grandmother in County Cork for seven years. That’s where he got his nickname “The Yank.” He returned to America in 1927 and worked in New York building roads and the New York City subway before moving back to Butte in 1932. He has remained there ever since, returning to Ireland only once for a visit in 1970.

Photos by Bill Rautio

Folklorist and storyteller Kevin Shannon recalls his own memories of Butte as a boy and preserves Butte’s Irish character through his many stories and jokes. Meanwhile, the documents of Butte’s history are gathered and stored by his daughter Ellen who manages the Butte-Silver Bow Archives.

After several years away from Butte, Jerry Sullivan returned to his hometown to open a new bank, the Granite Mountain Bank. Like other Irish Americans in Butte through the years, he keeps an eye on developments in Ireland and he spends a lot of energy on Project Children, a program that brings children from Northern Ireland to the United States to explore their differences and common interests.

Of course, the ultimate expression and celebration of Butte’s Irishness is the St. Patrick’s Day celebration that now draws about 30,000 revelers each March 17 to its historic uptown district to enjoy the parade led by the Ancient Order of Hibernians and celebrate in bars such as Maloney’s, the M&M, and the Irish Times, where Tom Wilde has recreated an Irish pub complete with booths made from church pews imported from Ireland.

There is frequent traffic between Ireland and Butte as residents renew family ties in Ireland and Irish come to visit a place that feels like home in the wilds of Montana.

Marcus Daly is not forgotten in Butte, where there is a statue of him by Augustus St. Gaudens. He made loyal friends and was beloved by the thousands of Irish who came to work in his mines. He died in 1900, in the Netherlands Hotel in New York City from complications of diabetes and a bad heart. He was 58 years old. He is buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn. At his death the Butte Miners Union acknowledged Daly’s role as “an honored friend and neighbor, whose loss this union sincerely bewails.”

Margaret continued to live in Montana until her death in 1941. She too, is buried in the family mausoleum in Brooklyn.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the August / September 2000 issue of Irish America.

I am pretty certain the “Con” my grandda talked about so much in his writings, is this same “Con” you mention. I am currently working on publishing my grandda’s works all about the mines. Thanks so much for this article. I will follow up on this connection. My grandda on my mam’s side was Marsh Wayne Donegan and my uncle her brother DaWayne Buck Donegan, also worked for the Anaconda Company. My grandda’s family was from Slane in county Meath Ireland. My gramps on my da’s side was Virgil James McNeil and he worked in Berkly Pit for most of his mining career.