Gerard Shields profiles Mayor Martin O’Malley

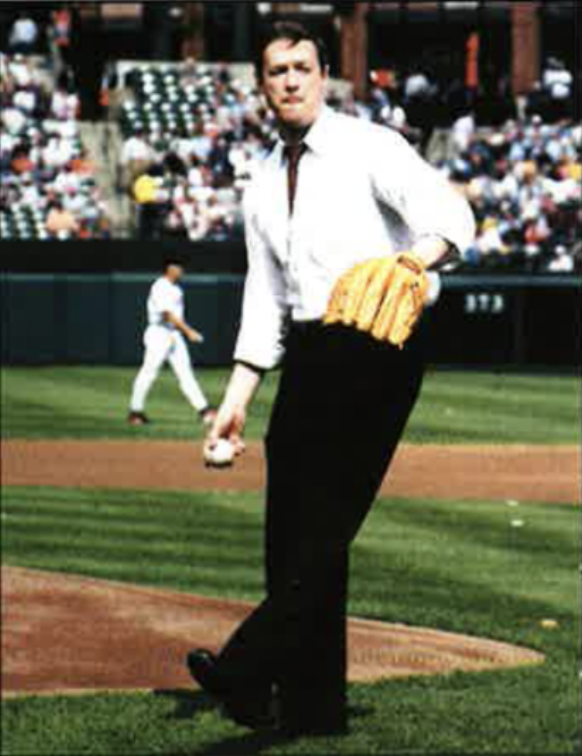

New Baltimore Mayor Martin O’Malley is renewing this harbor city’s long Irish ties not only by his stunning election in a predominantly African-American city but also as leader of the area’s most popular Celtic rock band, O’Malley’s March.

Brimming with knowledge of Irish history and rebel song, the 37-year-old former lawyer and City Councilman was inaugurated in December after capturing 54 percent of the city vote.

With his brash, confrontational style, biting wit and trademark impatience, O’Malley has already ruffled everyone from police chiefs to judges. The Catholic University graduate has also grabbed the attention of Baltimore masses with a crisp tenor voice that has laced two popular CDs of Irish-American songs, many of which O’Malley wrote himself.

“He’s the Pied Piper of Baltimore,” said Wendy Royalty, former Baltimore deputy health commissioner.

O’Malley started in politics in 1983 as the 20-year-old field director for former Colorado Sen. Gary Hart’s Iowa presidential campaign and has since entwined music and politics. Armed in America’s heartland with only a phone, congressional district maps and voter lists, O’Malley wooed farmers to pharmacists with his movie star looks, an acoustic guitar slung over his shoulder and a penny whistle in his pocket.

“The kid galvanized people,” former Hart deputy campaign manager Doug Wilson said. “You could see the fire in his eyes.”

O’Malley’s mother, Barbara, nurtured her son’s political passion in the Washington, D.C. suburbs, where she has worked for the last 13 years as a state senator’s aide. Like most Irish-American homes, the O’Malley clan posted the commensurate John F. Kennedy portrait. But O’Malley’s attorney father, Thomas, taught his son and five other children political science from the front row. He had Martin handing out political leaflets by age seven and more importantly, watching the returns.

“My father always made a big point of telling us, `See those votes coming in? You were involved in that,'” O’Malley recalls.

Gaining his first taste of campaigning at the Jesuit-based Gonzaga High School, where he ran for student council on a recycling program, O’Malley won a seat on the Baltimore City Council when he was 28 and quickly emerged as the political nemesis of former Mayor Kurt L. Schmoke. With starched pressed shirt and stiff white collar giving him the look of Michael Collins, O’Malley fostered the image with tight fisted, impassioned council floor diatribes decrying the city’s soaring crime rate, rampant political patronage and wasteful spending.

“He’s like a pit bull,” said Gary McLhinney, president of the Baltimore Fraternal Order of Police. “If he gets a hold of you, he’s not going to let go until you give up. The more you fight, the harder he bites.”

When Schmoke stepped down last year after a 12-year tenure, a field of 27 mayoral candidates formed to succeed him. O’Malley jumped in with polls showing him carrying a measly seven percent support. Political analysts viewed his candidacy as hopeless in a city with a 65 percent black population.

Yet the tireless O’Malley hit the streets vigorously, raising more than $1 million in three months and convincing Baltimore’s most traditionally active voters — African-American woman over 55 — to take a chance on his pledge to dramatically reduce the 300 yearly murders plaguing Baltimore.

“I knew being white was a handicap,” said the father of three whose wife, Katie, is a dynamo in her own right as a state prosecutor. “But to not run because of the color of my skin would have been to sell folks short. Because nobody, not black, white, green or blue, has low expectations for their city government.”

Retired schoolteacher Wilhelmena Vaughn was one of the black women who threw her support toward O’Malley. Vaughn’ s daughter was murdered several years ago, the killer never convicted. The West Baltimore community activist backed O’Malley’s tough crime-fighting pledge, even starring in a campaign television commercial where she told fellow Baltimore African-Americans that O’Malley had the vision necessary to turn the city around.

“I don’t care if he’s blue, green, black or pink,” Vaughn said. “As long as he gets the job done.”

O’Malley wasted little time making an impact. Of his first critical cabinet picks, four were African-Americans, including the police chief.

O’Malley credits his knowledge of Irish history with helping him empathize with the plight of Baltimore blacks. O’Malley said he understands the need for City Hall to reach out to blacks, who suffer the highest share of poverty, joblessness, drug abuse and murder in Baltimore, much like Irish Catholics persecuted under centuries of British rule,

“There is more that unites us than divides us,” O’Malley said. “No matter how successful the Irish have become in America, we’re only a few generations and a boat ride from poverty and oppression.”

Within days of stepping into office, the new mayor showed that he knew how to be the city maestro voters sought. He donned an orange jump suit and rode the back of city trash trucks, leading an army of public works employees in a major sweep of Baltimore’s main thoroughfares. Within three months, he ordered 1,800 city workers — including his deputy mayor and high school pal — to turn in free on-street parking passes after complaints surfaced that they were taking up coveted downtown slots.

And Baltimore’s 47th mayor helped save 350 jobs shortly after he took office by convincing CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield to drop its plans to move to the suburbs. O’Malley helped negotiate a long-term parking deal that owners viewed as critical.

“He has the energy of three people,” said William L. Jews, CareFirst president. “I have found him to be extremely responsive, caring and sincerely interested in making sure that the charge he received from citizens is coming about.”

O’Malley’s first six months in office hasn’t been all smooth sailing.

City judges balked at the mayor’s request for them to work nights and weekends by staffing a city jail courtroom to help reduce the caseload. Two Baltimore murder suspects walked free after a judge ruled their case had not been tried in a timely fashion.

Appearing before a panel of state legislators reviewing the problem, O’Malley told them he wanted to “throw up” at judges’ contentions that the city courts were improving. The battle escalated a week later when the chief judge complained that O’Malley didn’t fully explain his courtroom plan.

The outraged mayor, a former state prosecutor, responded by sending some of the state’s highest-ranking jurists elementary stick figure drawings illustrating the arrest and court process. The graphics found their way into the press, and within weeks, the judges acquiesced.

“It may appear to be flip, but he is fully aware of what he’s doing,” said Baltimore City Councilwoman Helen Holton. “When he believes in something, he is very passionate and he will convey the message in a way best understood by the most amount of people.”

Carol Arscott, a political consultant who studied the mayoral race, said O’Malley scored big points with city residents for standing up to the imperial judiciary. “He makes you want to stand and cheer,” Arscott said.

The mayor’s chief setback so far, however, has been the quick resignation of his police chief, Ronald L. Daniel. Daniel stepped down after just 57 days, refusing to endorse O’Malley’s crime-fighting plan.

Shortly after winning the election, O’Malley convinced city business leaders to hire former New York Deputy Police Commissioner Jack Maple to help revamp the Baltimore department. Maple had become a national legend after rising from New York subway cop to developing the computerized crime-fighting strategy that helped New York cut its annual murder rate from 2,200 five years ago to just under 700.

The model, which also requires aggressive tracking of violent fugitives, has recently come under fire due to the New York police shootings of three unarmed African-American men in the last 18 months. Daniel’s resignation over what he called his lack of input on the crime plan left O’Malley elevating the department’s second in command, newly hired former New York Deputy Commissioner Ed Norris. O’Malley’s African-American political opponents criticized the choice, holding protests over Norris, who is white. Yet the mayor took to the streets to defuse the tensions, holding three weeks of town meetings — some lasting as long as six hours — where he pledged to equally “police the police.”

“Baltimore is going to be the biggest law enforcement win in America,” said Maple, who helped New Orleans, Newark and Philadelphia dramatically reduce their murder rate. “They have the necessary ingredient to succeed: a mayor with the political will to get it done.”

Despite the long, gruelling days in the office, O’Malley continues keeping a rigorous band schedule. Where others might curl up with a book or jog six miles a day to relieve stress, the mayor rocks into the wee hours of the morning at places like Mick O’Shea’s Irish Pub and Restaurant in downtown Baltimore.

Wearing a black muscle shirt with cut-off sleeves, O’Malley pounds out Irish rebel classics such as “Black and Tans” on his acoustic guitar with jackhammer force, peppering the place with his own compositions, including “Song for Justice,” an ode to lives claimed in Northern Ireland’s centuries of struggle.

Yet much like in the political arena, O’Malley can shift his musical mood from stormy to compassionate, dropping into a whispery tribute to St. Mary’s light, the blue glow atop a South Baltimore church that once guided sailors into harbor.

In March, the six-member band with uilleann pipes and harp completed its second CD, Wait for Me. Locally, the recording is outselling Grammy Award-winning Santana.

“I do it because I enjoy doing it,” O’Malley said. “I played a full weekend this past weekend and felt so much better afterward.”

City residents enjoy it too. The mayor and his band were recently invited to play with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, where patrons filled two nights with rousing applause.

“I think it’s a wonderful thing for music and the city,” said symphony trumpeter Langston Fitzgerald.

O’Malley’s musical talent recently attracted the interest of the President of Ireland, Mary McAleese. Ireland’s second consecutive female president made a special trip to Baltimore during her recent five-day tour to meet O’Malley.

McAleese lauded the mayor for resurrecting interest in the land of his grandfather that made Baltimore one of the largest Irish immigration intake centers of America during the 19th century. McAleese noted that many of those residents left from a small Irish port in County Cork of the same name Baltimore.

“It’s exciting to come to a city where the mayor is named O’Malley,” McAleese said. “When the Irish do well in America, it energizes us at home.”

Six months into his mayoral tenure, O’Malley is gaining high marks for the reforms he has already initiated in the city court system and police department. And because of his youth, political analysts 42 miles south in Washington, D.C. are already talking about O’Malley as a possible presidential candidate down the road.

“He’ll hit some high notes and he’ll sing the blues,” said Maryland U.S. Senator Barbara Mikulski. “But we’re all ready to get behind O’Malley’s march.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the August / September 2000 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply