When I wrote the American Film Institute’s Life Achievement Award tribute to John Huston in 1983, I had the delightful opportunity to work with his daughter Anjelica. With warmth and enthusiasm, she hosted a segment of our CBS-TV special featuring testimonials by her father’s colleagues. Then thirty-one years old, Anjelica seemed like a young gazelle, an exotically beautiful and potentially graceful creature just learning to stand awkwardly on her own long legs. It wasn’t until later that I realized the source of her lack of poise that night: her insecurity performing in front of her legendary father, whose reactions to Anjelica’s earnest expressions of love seemed strangely unresponsive.

Anjelica Huston had clashed with her father while making her film debut as a teenager in the lead female role of his medieval saga A Walk with Love and Death (1969). Though her acting skills were raw, she had a strong screen presence even then, and the film was visually stunning. But aside from her brief role in her father’s 1969 Irish comedy Sinful Davey, they did not work again until Prizzi’s Honor in 1985. That stylish black comedy gave Anjelica a sparkling role as the hardboiled but droll Mafia dame Maerose Prizzi. Seizing the opportunity with alacrity, she won an Academy Award for best supporting actress.

Since then, thanks in part to her father’s belated show of confidence in her talents and also perhaps to the loss of his intimidating presence, her career has bloomed almost miraculously. Her haunting performance as Greta Conroy in her father’s last film, The Dead (1987), based on the James Joyce short story, sealed her cinematic maturity. By now, at the age of forty-eight, that once-awkward young woman has fully earned her place in the Huston filmmaking dynasty as a richly accomplished actress and director.

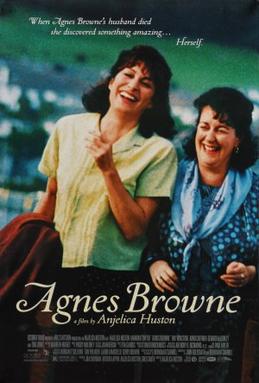

She made a stunning directorial debut in 1996 with Bastard out of Carolina, a Showtime cable movie based on the memoir by Dorothy Allison. One of the most harrowing explorations of child abuse ever put on the screen, it is the work of an assured filmmaker who knows how to make a period setting come vividly alive on screen while populating it with complex and believable characters. Now she has demonstrated her versatility by directing and starring in the seriocomic Agnes Browne, her captivating film version of comedian-playwright Brendan O’Carroll’s 1994 best-selling Irish novel The Mammy.

Although born in California (her mother was Huston’s fourth wife, Ricki Soma, who died in a 1969 automobile accident), Anjelica spent much of her childhood and adolescence in Ireland, living on her father’s baronial estate in County Galway, St. Clerans. She says of Agnes Browne, “I chose to make this film because it brought me back to Ireland — the emotional landscape of my childhood.”

Her Irish roots are reflected in her effortless incarnation of Agnes, whom she endows with an unforced Dublin accent. This doughty Irish widow, who raises seven children in 1967 by running a fruit and vegetable stall, is in many ways the antithesis of the passive, almost catatonically defeated Irish mother depicted in the film version of Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes. Agnes also stands in strong contrast to Jennifer Jason Leigh’s chilling portrait of a criminally irresponsible mother in Bastard out of Carolina.

Huston’s un-condescendingly affectionate view of working-class Dubliners gives Agnes Browne an infectious vitality. Her Agnes is a tribute to the resilient spirit of Irish womanhood. The script by O’Carroll and John Goldsmith follows the book fairly closely but enriches it by fleshing out some episodes, such as Agnes’s romance with a loopy, longhaired French baker named Pierre (Arno Chevrier). The tendency toward caricature that mars the novel is kept to a minimum in the film, replaced with more rounded characterizations and moments of deeper emotion, smoothly interwoven with comedy.

Agnes and her best friend Marion (marvelously played by screen newcomer Marion O’Dwyer) are just emerging into pre-feminist consciousness. They refer to the moment of intense sexual pleasure as “the organism.” Marion admits, “It was like getting ten early numbers in the bingo.” But Huston realizes that a little of this joshing about Irish sexual backwardness goes a long way. Agnes no longer reacts in horror (“Yeh…yeh pervert!”) as Pierre uses his tongue in giving her a goodnight kiss. This is one of the advantages of having a female director.

Huston’s direction is graceful and flowing, creating a sense of life going on around Agnes and her lively brood. Her handling of the camera has an ease that recalls her father’s quietly virtuosic camerawork. As he explained to me in 1975, in an observation he presumably imparted to his daughter as well, “I’m quite elaborate with the camera, but that goes unobserved, as it should. That way you get three shots for the price of one, and the audience’s mind is free to follow what it wants to follow. Time magazine, at the end of its film reviews, used to write, `Best shot,’ and they would always have a shot a good director would never dream of using — such as somebody reflected in a doorknob.” There are no doorknob shots in Agnes Browne. The director collaborates again with Anthony Richmond, the splendid British cinematographer who also shot Bastard out of Carolina, but in a much different style, as moody and dank as Agnes Browne is bright and lively. Though the milieu of the new film is realistically unglamorized, frequent splashes of bright color reflect Agnes’s essential jollity.

What’s most remarkable about the story is the utter lack of grief this widow displays. The audience assumes that Agnes is in denial and expects that she eventually will break down in tears, but it never happens. Gradually we understand that O’Carroll and Huston are showing that sometimes a woman can be better off without a man, particularly a no-account chancer like the late Nicholas (Redser) Browne. (Just imagine how much better off Angela McCourt would have been if her alcoholic husband hadn’t kept returning and if she had been forced to abandon her false hopes earlier in life.)

The avoidance of conventional sentimentality about widowhood in Agnes Browne becomes bracing. Redser’s funeral, treated as pure farce, becomes a raucously Irish celebration of life. This defiant attitude makes all the more powerful Agnes’s utter helplessness when Marion is stricken with serious illness. The film’s abrupt shifts of tone are adroitly handled and impart a feeling of life’s true unpredictability.

Though not a terribly sophisticated woman, Agnes has abundant savoir faire and a blithe confidence in her coping abilities. If there is a flaw in the film, it is that the Brownes’ economic circumstances seem a bit too rosy. Perhaps Huston’s privileged upbringing has left her unaware of what it is like to live on limited resources. Supporting seven children on her own causes Agnes remarkably little exhaustion or desperation.

In one affecting scene, she tells the children she needs their help, because she can’t do it without them. But mostly the film stresses the vital role of communal support in Irish life. Agnes is kept afloat not only by her job but also by the safety net of the dole, the timely arrival of a stipend from her late husband’s union, and, most of all, by the cheerful willingness of friends and neighbors to pitch in when help is needed. To American eyes in an era when political candidates boast about dismantling the safety net for the poor, this vision of mutual responsibility seems exotically appealing.

Events in Agnes Browne humorously conspire again and again to rescue the title character. The most surreal touch is the appearance late in the film of singer Tom Jones as a deus ex machina. Replacing her idol in the book, Cliff Richard, Agnes’s favorite pop singer is commandeered by her children to deal with a threatening loan shark. The prevailing mood of joie de vivre is encapsulated when Jones gives Agnes her well-earned serenade, “She’s a Lady.”

Another amiable new Irish film, The Closer You Get, also boasts a female director. A Scottish theater director and first-time feature filmmaker, Aileen Ritchie brings a keen satirical eye to the absurdities of mating habits in rural Ireland.

Written by William Ivory from a story by Herbie Wave, the film has a storyline that, if summarized, would seem to follow the same crushingly obvious vein of humor as a book entitled Brace Yourself, Bridget!: The Official Irish Sex Manual (1982) — a book consisting of 100 blank pages. The film’s fictional village of Kilvara in County Donegal seems populated entirely by people who don’t have a clue about how to proceed with procreation; it’s a wonder that the village is populated at all.

The local bachelors, unable to deal with the real women right under their eyes, take out an ad in a Miami newspaper seeking “fit and sporty” American women for their annual St. Martha’s Day Dance. Not surprisingly, the doors of the daily bus to Kilvara keep opening and closing without disgorging any American women. The understandably frustrated and angry local women learn of the men’s inept fantasizing when the postmistress, Mary (Ruth McCabe), routinely steams open the village’s most interesting mail.

The women take revenge by recruiting a bunch of Spanish sailors as uninhibited dancing partners. The tongue-tied, painfully shy Irish bachelors watch the spectacle with seething, helpless rage and despair. The initially farcical mood of the dance begins to take on something of the melancholy edge of the classic 1981 Irish TV movie The Ballroom of Romance.

Some Irish people no doubt will take offense in the comic exaggeration of The Closer You Get, dealing as it does with sexual repression, which can be a most uncomfortably close-to-the-bone subject for those who have been forced to deal with it. But the film’s satire is always good-natured, and the performances by a fine ensemble cast of both veterans and newcomers are touchingly real.

The depiction of sexual anxieties and clumsiness is not only universal in its application, but touches an indisputable chord of truth about a society still struggling to emerge from its long legacy of sexual guilt. Nowhere is this better depicted than in the scene of the handsome young priest, Father Mallone (Risteard Cooper), earnestly trying to counsel his male parishioners about sex but being unable to address the subject except metaphorically.

With the benefit of her extensive theater background, Ritchie is able to keep the actors playing the benighted bachelors and their female counterparts from slipping into caricature by bringing out three-dimensional shadings. There’s the Marty-ish butcher, Kieran O’Donnagh (Ian Hart), a ridiculously arrogant fool who fails to realize that he’s in love with his fierce young helper, Siobhan (Cathleen Bradley). More delicate notes are struck by the tentative attraction between the unhappily married barmaid Kate (Niamh Cusack) and Kieran’s older brother Ian (Sean McGinley), who’s more comfortable around his sheep.

The most touching of the film’s several romances is that of chubby middle-aged Ollie (Pat Shortt), who orders sex magazines from Amsterdam that Mary, the outraged postmistress, refuses to hand across the counter. When Ollie bursts into a poetic aria about his thwarted dreams of romance, Mary, who appeared resigned to life without a man, summons up the boldness to ask him out for a walk. Their faces are rapturous as they lie together in the bed of a tractor in a joyously unexpected postcoital scene. As the various couples pair off in classic romantic-comedy style, Kilvara is assured of a more fruitful future.

Unlike Agnes Browne, which refuses to allow its proud tide character to fall into self-pity, The Closer You Get deals with people who initially wallow in that futile emotion. But the same kind of imaginative spirit that allows Agnes to blithely transcend her seemingly treacherous surroundings ultimately lifts these lives of quiet desperation. Both films exhibit one of the most exhilarating attributes of comedy, its role as a conveyor of hope.

Leave a Reply