Anyone who has read Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes — and by now that probably takes in about half the planet — knows that what makes McCourt’s memoir of an impoverished Irish childhood so magical is the unique “voice” the author uses to tell the story. McCourt struggled for many years until he “started writing in the voice of a child, immediate, urgent and without hindsight or foresight.”

Recounting his often horrific upbringing in that voice makes the story bearable, while allowing the reader to understand how young Frank could have survived his circumstances so triumphantly. The author’s voice also carries with it an overtone of irony — sometimes gentle, sometimes brutal — as the sexagenarian schoolteacher looks back over his childhood and hears what Wordsworth called “the still, sad music of humanity.”

Adapting a book into a film, particularly one that so many people from so many diverse backgrounds have taken to their hearts, is a minefield of potential disasters. However faithful the screenwriter and director may want to be, they can’t simply stage a succession of scenes directly from the book and expect the film to replicate the reading experience. What’s necessary is to re-imagine the story for the screen, for movies are a visual and aural medium with far more physical specificity than a book and far less opportunity to enter into the characters’ minds.

Adaptation is such a difficult task, in fact, that it’s almost a miracle when a first-rate work of literature is made into a good movie. Most adaptations of famous books are overly slavish, because the filmmakers are afraid to offend readers by leaving out their favorite scenes. Producer David O. Selznick and his legion of screenwriters managed to cram the essence of Margaret Mitchell’s massive novel Gone With the Wind into a four-hour film, but the second half still feels too episodic and rushed. The reductio ad absurdum of misguided faithfulness was Selznick’s decree that his writers could not use a word in their script if it did not appear somewhere in Mitchell’s book.

Adapters usually need to be unfaithful in particulars in order to be faithful in spirit to the original work. One of the finest examples is John Huston’s 1975 film of Rudyard Kipling’s classic short story “The Man Who Would Be King”. Much of the dialogue and some of the incidents were invented by Huston and his writing collaborator Gladys Hill, yet it all feels like Kipling, with an overlay of Hustonian cynicism. The secret of adaptation, Huston told me at the time, is to immerse oneself in the author’s world until you can speak effortlessly in his voice. Huston had been reading Kipling since boyhood, and fragments and echoes of Kipling’s other stories can be found throughout his magnificent film of “The Man Who Would Be King”.

But it’s virtually impossible to make a film that consistently takes a single character’s point of view, as McCourt does in Angela’s Ashes. A film observes action from so many diverse physical perspectives that ultimately the only point of view that matters is that of the filmmaker. Alan Parker, who directed and co-wrote (with Laura Jones) Angela’s Ashes, showed a genuine feeling for the serio-comedy of everyday Irish life in his marvelous 1991 adaptation of Roddy Doyle’s novel The Commitments. But Parker’s attempts to find an appropriate cinematic style for Angela’s Ashes are mostly unsuccessful.

Since Parker cannot pretend to be McCourt, the film’s fitful attempts to imitate the book’s first-person, present-tense style seem labored. An adult actor (Andrew Bennett) narrates certain scenes, but the device is used erratically; there should have been more narration or none at all. When Parker attempts to look at the material more objectively, taking the viewpoint of other characters as well as that of young Frank, he simply muddies the waters, because he can never seem to find his own directorial “voice.”

Although I tried to see the film as much as possible on its own merits, I couldn’t help wondering why Parker and Jones omitted the haunting episode of young Frank’s interaction with a dying girl when he is hospitalized with typhoid. I also miss the passage dealing with Frank’s ministration to his gravely ill mother, a trial that becomes a key element in his maturation. And though Frank’s hunchbacked friend “Quasimodo” appears in the film (played by Eamonn Owens), who gave such an electrifying performance in The Butcher Boy, the film’s Quasimodo no longer tries to compensate for his physical appearance by training himself to talk like a BBC radio announcer. The loss of these elements of transcendence, lighting the way to Frank’s future, diminishes the story.

Outwardly, though, Angela’s Ashes strives mightily to be “faithful” to the book. The physical look of lower-class Limerick from 1935 through the late forties has been meticulously re-created on various locations (including Dublin and Cork), even if too much of the film takes place on stagey sets of the McCourts’ home in cramped Roden Lane.

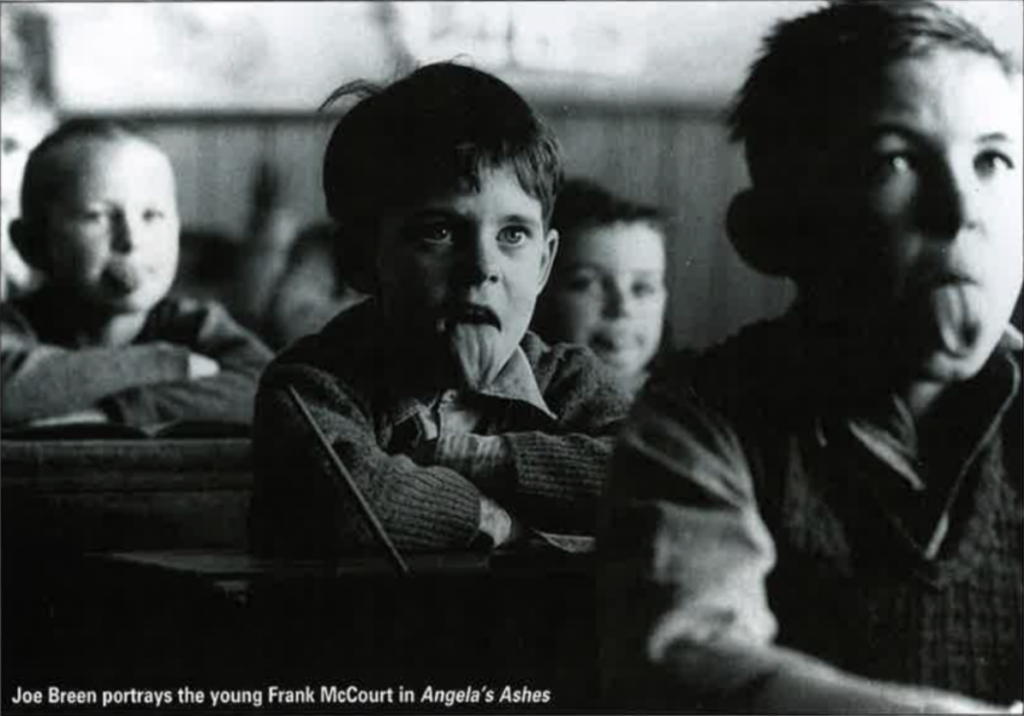

No fault can be found with the casting, from the parents (Emily Watson and Robert Carlyle) to the three boys who play Frank from age five through adolescence (Joe Breen, Ciaran Owens, and Michael Legge). But the essence of the story is lost. The film plays like one of McCourt’s rejected earlier drafts must have read when he still was searching for that elusive voice.

Angela’s Ashes has one almost insurmountable handicap as film material. It’s one thing to read about extreme poverty, but something else entirely to see it up there on the screen, with every awful detail magnified. Lacking the filtering device of the author’s memory, the constant knowledge that little Frankie will survive with his sanity intact, the viewer is left with a fresco of virtually unrelenting grimness during the first half of the film. With almost nothing to relieve the monotonous misery and squalor, the spectator numbs out emotionally rather than being drawn into an intimate empathy with the characters.

In the second half, Parker jumps around in tone and feeling as if trying out various narrative styles. There’s a welcome infusion of buoyant humor as Frankie becomes older and more independent, but it seems like a different movie, as if The Bicycle Thief had suddenly metamorphosed into E.T. Frankie still encounters moments of anguish as he grows up, but the escalating stylistic vitality makes them seem increasingly less consequential.

Another major hurdle in visualizing Angela’s Ashes is that the mother, although her name appears in the rifle, is a largely shadowy figure in the book, more an iconic force of survival than a three-dimensional person. The film has to make her real, but the screenplay fails to give Watson much to do except to sit around quietly taking care of her children with self-destructive resignation.

Watson is a fine and resourceful actress, but she becomes a cipher in Angela’s Ashes, showing little of the strength the mother has in the book. This flaw, coupled with the overly episodic nature of the screenplay, means that the overwhelming anguish we feel in the book over the death of Angela’s children is rarely felt onscreen. In one scene, however, Parker finds a cinematic equivalent of McCourt’s chilling prose, showing Frankie waking up in the middle of the night to realize that his little brother Oliver’s face has turned blue.

Robert Carlyle fares much better than Watson with his enriched role as the father, Malachy Sr. While in the book Malachy is little more than a figure of drunken futility, in the film he’s given more dignity as a man who at least keeps trying to find work, even if he continually fails to support his family. Since the character has more complexity, when we see and hear him spinning his fanciful tales to his son, we can understand better why Frank still loved and emulated him, and why Frank one day would learn (as Joyce wrote in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man) “to live, to err, to fall, to triumph, to recreate life out of life.”

One of Parker’s finest cinematic inventions is the way he edits the sequence of Frank watching his father walking out of his life forever. Eight years old as he stands in an archway seeing his father leave home to work in England, Frank has become an adolescent by the time we see him a few moments later, still watching vainly from the same archway. With more of such visual imagination, Parker could have made the experience of watching Angela’s Ashes approximate the indelible experience of reading the book.

I thought the movie followed the book as close as possible considering that it was two different concepts! I enjoyed both very much.