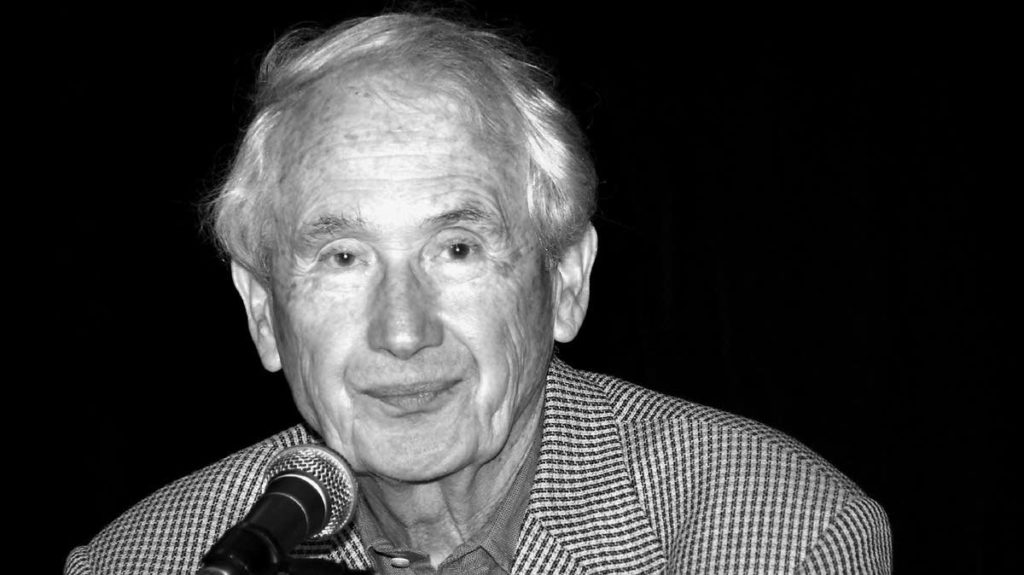

Frank McCourt is on an exhaustive book tour and won’t get a break until the middle of December when he gets back to New York for the premiere of the movie Angela’s Ashes. Towards the end of October, Irish America Editor-in-Chief Patricia Harty caught up with Frank on the phone from Palo Alto, California.

How are you?

Running, running, running from place to place, signing books and talking.

How does it feel to have both books number one on The New York Times best-seller lists?

Well, as someone said to me on the phone from New York, “Thank God, you are keeping Dutch out of first place.” Don’t know when that will change. [‘Tis] can’t stay up there forever, and I’m practicing humility for the inevitable.

Any fear of the [Irish] begrudgery factor setting in?

Not really. Of course you have that declining group of begrudgers in Limerick, but they can’t do anything about the fact that Jim Kemmy [recently deceased socialist T.D. for Limerick] wrote a powerful column about it [Angela’s Ashes]. They can’t do anything about the fact that hundreds of people turned out to audition for the movie — women were bringing babies in the womb. They can’t do anything about the fact that Angela’s Ashes and ‘Tis are leaping off the shelves in O’Mahoney’s bookshop [in Limerick].

What’s been the reaction to `Tis in Limerick?

They’re not as concerned with `Tis. The guardians of civic virtue are not as interested in my life in New York, but the Irish critics have been more peevish than anywhere else.

What do you think of the movie?

I see my life and it’s authentic. It’s faithful to the book — it captures the kids in particular. I think that Alan Parker has this great gift and that Emily Watson is beyond superlatives. If I didn’t like it I would be disappointed, but I don’t see how anyone could be disappointed with the movie.

How does it feel to be such a public figure?

I had a smaller measure of that when I was teaching. I was popular as a teacher and, especially in Stuyvesant High School, students would come up to me in the hallways. I used to wonder if I was too easy — but they tell me I was a good teacher. There are all kinds of people coming up to me and telling me how the book [Angela’s Ashes] touched their lives. Some will say it’s the only book they’ve ever read — young men especially who don’t want to admit they read a book. They talk about alcoholism and how it affected their lives, and about Ireland. For many it seems to be an opening-up. Does all the attention bother you?

I’m a late bloomer. No one paid me a scrap of attention when I was a teacher, so I don’t mind.

Any regrets about not doing all this sooner?

I wasn’t capable of it. I didn’t have it — didn’t have the knowledge that I gained as a teacher. Whatever I know I learned in the classroom. I tried to write a novel about Limerick about thirty years ago. It was all right. I still have it in the drawer. I take it out whenever I feel smug.

Any personal regrets?

I regret that I could have been kinder to my mother — I missed so many opportunities. There’s no high school course that teaches you how to deal with life. What happens if you get a divorce, for instance? The people I knew headed immediately for the bar — and I did too and it dimmed my faculties and my behavior wasn’t that praiseworthy.

Do you wish your mother had been kinder to you?

No. Her life was hard beyond description. She suffered too much as it was; she didn’t have to do any more than that.

Americans seem to be much better at expressing themselves in that area.

Especially Italians. I used to love watching Italians hugging and kissing each other. We didn’t do that. We would sing and die for Ireland and weep when Young Munsters lost a game. I remember once when Malachy told my mother he loved her, he was nine at the time, and she didn’t say anything. Later she told a neighbor and they both laughed about it — in front of him. It was a long time before he told anyone else that he loved them.

What does your daughter, Maggie, think of `Tis?

She loves it. She’s coming to the movie premiere of Angela’s Ashes in New York.

The magical thing about Angela’s Ashes is the child’s voice. How did that come about?

Purely accidentally. Right in the beginning I’m in a playground in Brooklyn with my brother and I wrote it in the present tense from the child’s perspective and it just came. And it was comfortable. Not many writers write about the comfort of finding the right voice.

Was it harder to get into the voice of the older Frank when you were writing’ Tis?

Well, certain parts of it were — it’s a story of bewilderment. It’s an immigrant’s story. I was ill equipped for America. It was very hard for me to admit that I was a pathetic creature. My favorite line from Hamlet is “Why, what an ass am I.” I was naive, innocent, and at times stupid.

When did that start to change?

In the first year and a half in America I just drifted around doing menial jobs, living in an Irish ghetto, not moving out of it. The Korean War saved me. The Army drafted me. I was sent to Germany and that opened up a larger world to me.

What about the attitude of the Irish on the Irish American? The Irish can he rather dismissive of the Irish American.

That’s changing, but this is an intriguing area, the relationship between the Irish and the Irish American. I was always regarded as Irish and rather patronized by Irish Americans, and relegated to the menial jobs, because they assumed I came off a farm. But then the Irish Americans were deferential towards the Irish because the real Irish were the keepers of the flame. Irish Americans would go to Ireland like they were visiting a shrine. They don’t know their own history — that they were so powerful and built up a network of universities and schools, dominated the church and politics and journalism in America.

What are your plans for the future?

To write a novel — mostly about teaching. It’s becoming more and more urgent for me to do this. So little has been written about teaching, and other than Goodbye, Mr. Chips, no movies. A novel gives me greater freedom to spread my wings. With ‘Tis I had to spend about six hours with Scribner’s legal department.

So you are still promoting the cause of teaching.

I’ve been invited to testify before a congressional committee on education in March — now I’m being seen as someone in the know. Teachers are particularly beside themselves because I’m always mentioning teaching. I’m probably the only one — I’m the voice now and I didn’t know this was going to happen. It’s a responsibility. The New York Times editorial board has said that they would like to sit down with me also.

Well, Frank, whatever you were in the past, I would say that at this stage in your life you are pretty confident.

[Laughs] I have a few convictions. There are a few things that I believe in; the rest is murky.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the January 2000 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply