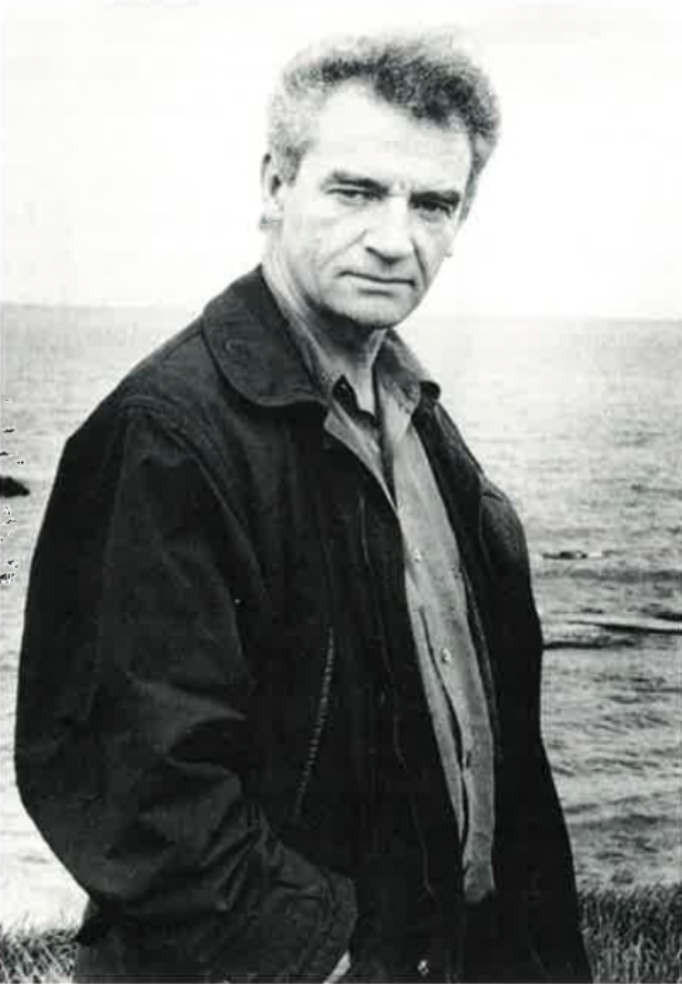

Seamus Deane, a renowned literary scholar, fills a void at Notre Dame

The University of Notre Dame, the home of the Fighting Irish, is the sentimental alma mater of many more actual and would-be Irish-Americans than ever have studied here.

Yet until now, the most identifiably Catholic institution in the country–one where 14 of 16 presidents have been priests of Irish birth or descent–has never had an Irish-studies program.

Last fall, Seamus Deane, a renowned literary scholar, was invited to Notre Dame to remedy that lack, aided by a $2.5-million gift to the university.

The reputation of Mr. Deane, a professor of modern English and American literature at University College, Dublin, rests on a broad range of achievements. He was general editor, for example, of the Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (W. W. Norton, 1991), a three-volume compendium of writing from the sixth century to the present. It has been widely acclaimed as the most important Irish publication in decades. (A fourth volume, containing the work of woman writers exclusively, is being prepared.)

The Irish-studies program at Notre Dame, too, will deal with writing from the whole 1,500-year expanse of Irish literary history, in Irish as well as English–and not just “the Golden Oldies: Yeats, Joyce, maybe Synge and O’Casey,” as Mr. Deane puts it. That will immediately set it apart from all but a few Irish-studies programs in this country.

Writing’s Place in Irish History

The Field Day Anthology laid the groundwork for a re-evaluation of the place of writing in Irish history. As an act of post-colonial protest, it aimed to reclaim Irish writing long appropriated by the English national literary canon.

The anthology has proved a high point in the work of the Field Day Theatre and Publishing Company, a Derry-based cooperative of writers and scholars, of which Mr. Deane is one of six directors. Its pamphlets and theatrical productions have greatly influenced the debate on Irish political and cultural issues.

So has Mr. Deane’s scholarship–consistently. In Celtic Revivals: Essays in Modern Irish Literature, 1880-1980 (Wake Forest University Press, 1987), for example, he emphasized Ireland’s literary resilience despite repeated invasions. Also among his publications is A Short History of Irish Literature (University of Notre Dame Press, 1986).

Mr. Deane has not focused exclusively on Ireland, however. He was raised in the North, in a working-class family in Derry. As part of the city’s Catholic minority, he was “highly politicized from the outset,” he notes. Yet it was to Europe and England that his interest turned. He studied English literature and French Enlightenment thought, first at Queen’s University in Belfast, then at Cambridge University. Those interests led to the publication in 1988 of The French Revolution and Enlightenment in England (Harvard University Press, 1988).

He has also published some 70 journal essays, and, in addition, five books of poetry. His first novel, Reading in the Dark, is forthcoming from Granta Books.

Those achievements have made the unassuming Mr. Deane as highly admired as he is widely liked. Says David Lloyd, an Irish literary and cultural scholar who teaches at the University of California at Berkeley: “Deane is clearly the principal Irish intellectual at the moment. There’s no doubt about that.” Mr. Deane has attained, Mr. Lloyd adds, not just academic prestige, but the stature of a “moving spirit” for a generation of Irish scholars.

“This seems like the perfect appointment for Notre Dame to make,” says Christopher Fox, the chairman of the university’s English department, where Irish studies will be housed. He calls Mr. Deane “arguably the top Joyce scholar in the world,” who has also written “probably the standard history of Irish literature.” In 1992, Mr. Deane edited and introduced Penguin’s six-volume edition of the works of James Joyce.

Mr. Deane will spend one semester a year at Notre Dame for at least three years. His program will entail creating new courses and pulling together existing courses from various departments, first at the undergraduate level. Graduate courses are planned for the future.

Above all, Mr. Deane says, he came to Notre Dame because he was more interested in having an opportunity to shape Irish studies in the United States than in offers to teach modernism or postcolonial studies elsewhere. He will, in any case, now be closer geographically to other leading scholars of postcolonialism with whom he has worked, including Edward Said and Fredric Jameson.

He says he wants to give his program “some particular kind of distinction.” Its unusually wide scope alone will do that. And the program’s location here may give it added punch, given that Mr. Deane says he and his colleagues at Field Day consider Notre Dame “a place which might have been a nurturer of precisely the kinds of stereotypes that would worry us.”

Immutable Stereotypes

The two predominant stereotypes of the Irish, he says, are that they are very violent and poetic. Although they originated in England to justify colonial rule, those stereotypes are so strong that even the Irish and Irish Americans identify with them. “Maybe the best thing to do is to step into the center and to start changing from there,” he says.

Mr. Deane aims first to acquire important library collections relating to Irish literature and thought. “Before we can do serious work, we need library holdings in depth,” he says.

That project has already begun, financed by a $2.5-million gift from Donald and Marilyn Keough. Mr. Keough, chairman emeritus of Notre Dame’s Board of Trustees, recently retired as president of the Coca-Cola Company.

The major challenge, Mr. Deane says, will be to find resources to support the program in its breadth–some teaching of the Irish language and literature in Irish, from the seventh century to today, and of Irish history, philosophy, and other subjects. Again, the purpose of that kind of scope is simple, he says: “To understand how we got into this mess in the North, we’ve got to understand the history, the genesis, and the force of the stereotypical patterns according to which all of us, Catholics and Protestants, are performing.”

A “Phantom Bullet”

The political nature of the literary revival is no secret. On this subject, Mr. Deane is clear: “In the Northern situation, I would quite frankly say you can’t solve that situation, you can’t introduce peace, unless you introduce justice, and you can’t introduce justice and preserve the Northern state.” He adds, with characteristic wryness: “But of course, when I say that, then people see the shadow of an Armalite in my hand. And so I say, ‘Here’s a phantom bullet. I call it a book.'”

Many of his critics in Ireland, he notes, see his cultural undertakings as agitation. Mr. Lloyd of Berkeley confirms that assessment, and applauds Mr. Deane for his resoluteness. “It’s a real credit to Seamus Deane that he has maintained his radical edge,” he says.

Mr. Fox, the chairman of the English department here, says that when he recommended hiring Mr. Deane, he reasoned that “the Irish Catholic kids at Notre Dame needed somebody like Seamus Deane to give them his sense of what it meant to be Irish.”

Certainly Mr. Deane stands ready to correct any romantic notions about Ireland — pro- or anti republican. “It’s a matter of great frustration to many people in Ireland,” he says, “that the American view of Ireland is so confined, and in many ways so anorexic.

“To understand the Northern Irish situation takes a long time and a great deal of care,” he says.

Nor will Notre Dame’s Catholicism, or his own beginnings as a “cradle Catholic,” damp his outspokenness. For instance, he says: “I have no patience with or time for any notion of a Catholic, Gaelic Ireland. None whatsoever. It would be as bad as a Protestant, English Ireland.”

Re-evaluating Yeats

A fresh look at Irish writing, he suggests, holds promise. He has been in the forefront of a re-evaluation of W. B. Yeats. In Mr. Deane’s reading of this most celebrated of Irish poets, Yeats actually crystallizes a whole system of colonialist attitudes. Yet Yeats voices his colonialist stripes so brilliantly that, far more fruitfully than lesser poets, he engages such issues as the inseparability of literature and politics, Mr. Deane says.

Part of Mr. Deane’s “personal effort,” as he puts it, has been “to recuperate James Joyce from what I have to say is the American liberal humanist view of him, and put him in a much more specific geographical, historical, colonial context.” This semester, he has been teaching an undergraduate course on the novelist and a graduate course on the Irish novel. So rapidly has his renown as a lecturer spread that the lecture halls have overflowed with listeners. “He’s very generous about letting everybody come in,” says Mr. Fox.

His assessment of Mr. Deane — “As a lecturer I’ve never seen anybody quite like him” — is shared by Brian Friel, the Field Day playwright. In a letter of recommendation to Notre Dame officials, Mr. Friel called Mr. Deane a brilliant lecturer, creative, persuasive, and fascinating. “His lectures are informed and crafted and satisfyingly complete occasions.”

Editor’s Note: *Originally published in Irish America’s March/April 1994 issue.

*Reprinted from The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Leave a Reply