Few things are sadder than a missed opportunity. The story of the San Patricios, the Irish emigrants and their comrades of other ethnic groups who fought for Mexico during the U.S.-Mexican War of 1846-48, is rich and underexplored dramatic material. Complex and stirring issues of loyalty and heroism resound throughout the saga of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion, which consisted largely (but not entirely) of Irishmen who deserted from the American army in the 1840s after being disillusioned by the ethnic and religious persecution they faced in their adopted land. They found a more congenial home south of the border, carrying a banner festooned with the Harp of Erin and identifying with the Mexican struggle against an imperialist invasion that reminded them of the British conquest of Ireland.

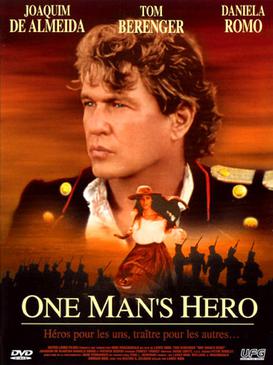

Filmmaker Mark R. Day explored the subject in his 1996 documentary The San Patricios: The Tragic Story of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion. It should be good news to report that this fascinating story has now been brought to the big screen as a dramatic feature by MGM. But One Man’s Hero, which had a brief U.S. theatrical release in September after its August opening in Ireland, was badly botched by director Lance Hool and his late screenwriter, Milton S. Gelman, who wrote the script about twenty years ago. Unfortunately, John Huston and Sam Peckinpah, who both expressed interest in making a film about the San Patricios, were not around to rewrite and direct One Man’s Hero, which takes its title from the saying “One man’s hero is another man’s traitor.”

Tom Berenger stars as Sergeant John Riley, the rugged Irish-American soldier who leads a band of comrades into the Mexican army. Berenger’s leathery face and no-nonsense style of acting lend a feeling of authenticity to any role he plays, and Riley is a character who invites audience empathy with his unconventional courage and protean ability to reinvent himself. Eventually, after living through hellish combat and literally being branded as a deserter by his former American comrades, Riley heads into the Mexican hills dressed in peasant garb. His decision to turn his back on the hypocrisy of American society and “go native” would have given the movie a solid foundation if the script and direction had not been clumsy to the point of amateurishness.

The problems in Gelman’s screenplay begin with the opening scene, a dismayingly wordy piece of exposition that has a bunch of Irish soldiers in a military brig explain who they are, why they’re in the army, why they’ re imprisoned, and what the filmmakers intend to teach the audience. Such crushingly literal-minded dialogue would ring a death knell for any story, but Hool compounds it throughout with hammer-handed direction that makes the film unintentionally comical, a straight version of Woody Allen’s Bananas. When Riley becomes enamored of a mestiza, played by Mexican TV star Daniela Romo, she solemnly explains, “We are this land, Riley, and the land belongs to the people who work it.” As if that’s not cornball enough, when Riley’s romantic rival, the rebel leader Cortina (Joaquim de Almeida), demands to know, “What is she to you?” Riley sententiously replies, “Mexico.”

Hool’s characters might as well walk around wearing sandwich boards advertising their allegorical functions. Even Riley and the charismatic Cortina are reduced to stock figures. You can’t help thinking of far more sophisticated Westerns dealing with Irish rebels, such as Peckinpah’s Major Dundee (1965) or Samuel Fuller’s Run of the Arrow (1957). In Major Dundee, Richard Harris plays Tyreen, an embittered Irish immigrant who deserts the Union Army to join the Confederacy. As a prisoner of his former army, Tyreen declares to Charlton Heston’s Major Dundee, “It’s not my country, Major. I damn its flag and I damn you. And I would rather hang than serve!” Rod Steiger is O’Meara in Run of the Arrow, the Irishman who fights for the Confederacy and then, refusing to admit that the war is over, joins the Sioux to continue his personal rebellion against the United States. Berenger’s plodding sincerity mostly lacks the spark of romantic madness Harris and Steiger bring to their performances.

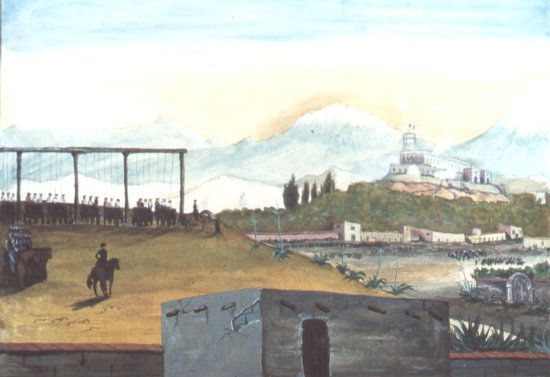

Far too much of the focus in One Man’s Hero is on the overheated romantic triangle, which is made to seem more momentous than the war itself. Most of the battle scenes are poorly staged, chaotic, and lack any dramatic point of view. Only toward the end does the movie gradually begin to show glimmers of life, when the San Patricios accept their doom in a lost cause and sacrifice themselves for their sense of honor. The situation is so inherently moving that Hool fitfully rises to the creative occasion, although he can’t resist protracting the conclusion interminably. His work still pales in comparison with the unforgettable existential bloodbath that climaxes Peckinpah’ s The Wild Bunch.

But even so weakly handed, the moral and political issues in One Man’s Hero have the capacity to stir controversy. Robert Koehler makes that clear in the Variety review of the film. Describing it as a story of “Irish-Americans pulling a collective Benedict Arnold,” Koehler criticizes One Man’s Hero for being “laden not only with a heavy pro-Irish sentiment but [also carrying] a strong whiff of post-Vietnam, anti-American politics” and “excising any background on U.S. motives for grabbing Mexican territory (which stretched north into what are now parts of Texas).” Given the firestorm I provoked with my negative Variety review of Patriot Games, I’m the last person who’d be surprised to find Variety taking a reactionary viewpoint toward a film about Irishmen opposed to U.S. belligerence. But it’s bizarre that as late as 1999, Variety actually believes there were valid “U.S. motives for grabbing Mexican territory” in a war that today is generally regarded as a shameful blot on American honor, an act of naked aggression carried out largely to expand the southwestern territory available for slavery.

Perhaps Mr. Koehler has never read the Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, whose distinguished military career included service as an officer in the U.S. army during the Mexican War. In his 1885 autobiography, completed shortly before his death, the former president did not mince words about that episode in our history: “For myself, I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day regard the war which resulted as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory…. Even if the annexation itself could be justified, the manner in which the subsequent war was forced upon Mexico cannot…. To us it was an empire and of incalculable value; but it might have been obtained by other means. The Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican war. Nations, like individuals, are punished for their transgressions. We got our punishment in the most sanguinary and expensive war of modern times.”

Perhaps if Gelman and Hool had been better craftsmen, they could have brought some of this passion and historical perspective to bear on One Man’s Hero. Some Tom Berenger fans started a grass-roots campaign on the Internet to urge MGM to give the film wider distribution. I’ve heard the argument raised that MGM deliberately threw away One Man’s Hero in the U.S. for political reasons by releasing it only in a few southwestern markets before shipping the prints to Mexico. But this is one case in which political considerations are not the main issue. If One Man’s Hero had been as artistically crafted as Run of the Arrow or The Wild Bunch, you can bet MGM would have marketed it gladly without worrying whether some people might regard the San Patricios as Benedict Arnolds. There is a lesson here for anyone trying to deal with complex historical subject matter on screen: If you blow it, be prepared to walk down that well-worn road paved with good intentions.

Leave a Reply