Frank Wild, the second in command, made his way through the ship as its planks buckled and heaved against the mounting pressure. Occasionally a loud crack rang out like a gunshot as the timber snapped under the strain. He worked his way from the crew’s quarters to the engine room and down to the propeller shaftway where two crewmembers were trying to reinforce a cofferdam that had been constructed to stem the flow of water pouring into the ship. Back up on deck, he found three crew members who had been working the pumps for three days straight and had finally given up, realizing the futility of their task. No one was surprised when Wild called out, “Abandon ship.” The crew of the Endurance had already resigned themselves to the fact that she was lost, and with her went the dream of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

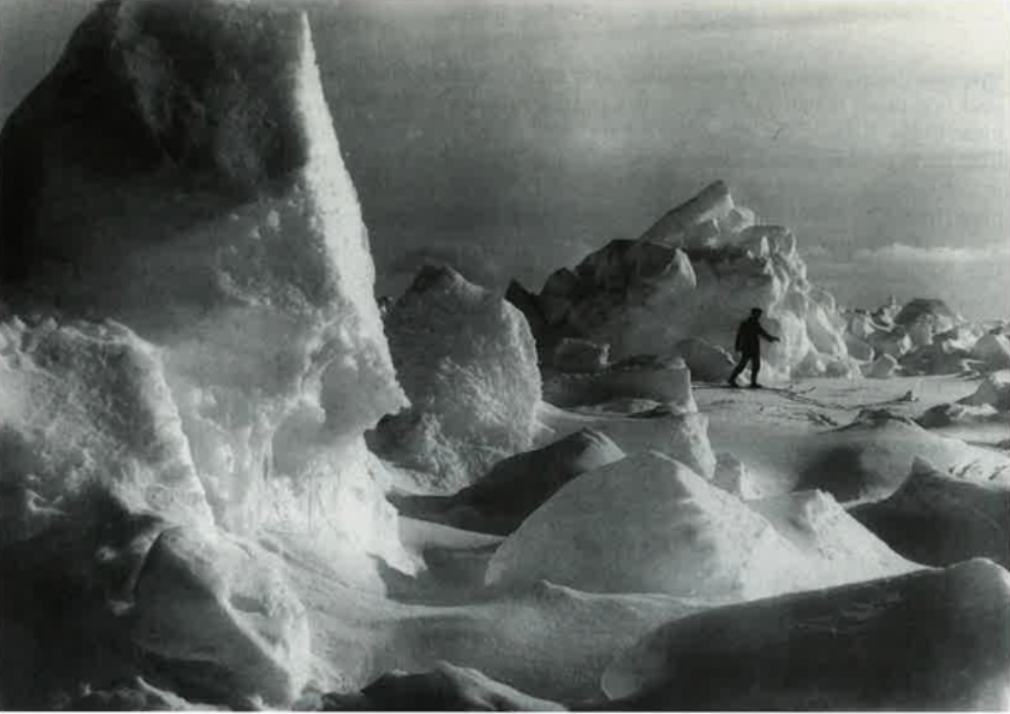

It was October 27, 1915, and the Endurance had been frozen in the pack ice of Antarctica’s Weddell Sea for more than ten months. Like a giant jigsaw puzzle of icebergs and floes, some stretching for hundreds of yards, pack ice drifts in the seas off the Antarctic coast. At its worst, the pack is so tight that there might not be a lead of free water for as far as the eye can see with the giant floes grinding against each other and forming giant pressure ridges.

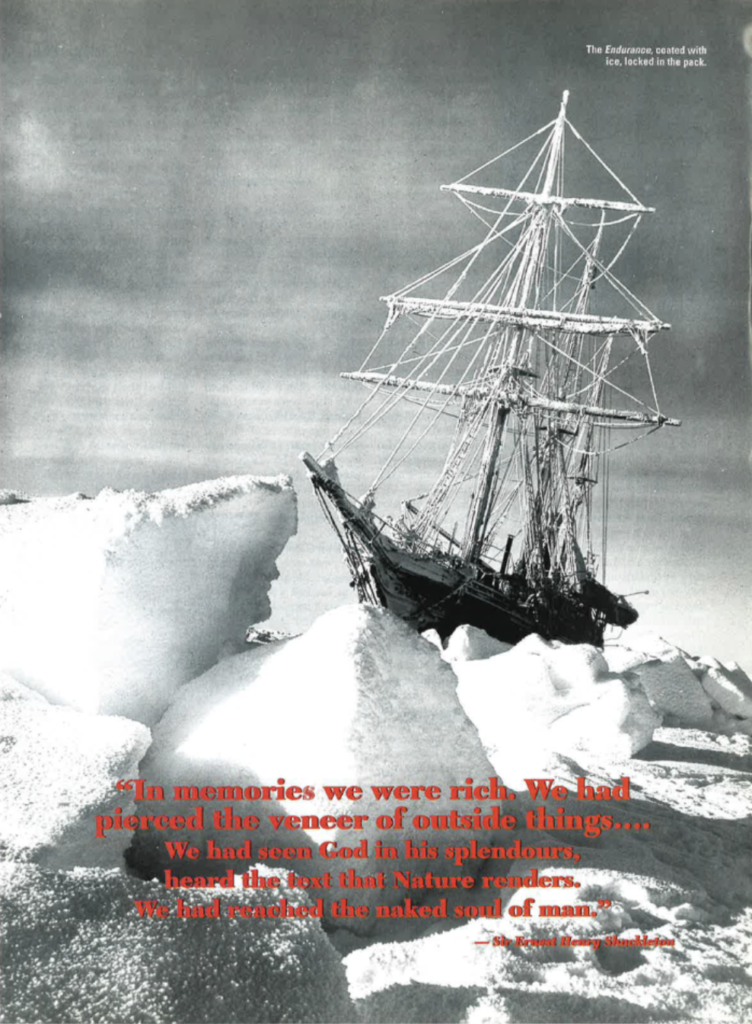

Finally, the shifting floes of ice began to slowly crush the Endurance like the jaws of a nutcracker. For three days, the crew fought to save the ship, until they were forced to accept that she was beyond rescue.

Led by an Irish-born explorer named Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton. The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition was to be the first crossing of the Antarctic Continent. England had already lost the race to both the North and South Poles to Norway, but the crossing of this mysterious continent remained an unclaimed prize.

The ill-fated expedition would have been Shackleton’s third trip to Antarctica. In 1901, he accompanied the famed explorer Robert F. Scott on his unsuccessful quest to reach the South Pole. Six years later he set out again, leading his own expedition in pursuit of the same goal. Less than 100 miles away from the Pole, further south than anyone had gone before, he was forced to turn back due to his party’s dwindling supplies and failing health. Shackleton always put his men first. This sense of personal responsibility for those he led distinguished him as an explorer.

The second of ten children, Ernest Henry Shackleton was born in County Kildare, Ireland on February 15, 1874. His father was a farmer but, with the repeated failure in his potato crops, took qualifications as a doctor in Dublin and moved the family to a suburb of London in 1884. While young Ernest was very bright, he was not interested in academics and at 16, he took to the high seas traveling around Cape Horn and to China and the Far East. He passed his examinations for Second and then First Mate and by 1898 he was a Master, certified to command any British ship on any ocean.

He was twenty-seven when he volunteered for Robert Scott’s Discovery expedition to the South Pole. While the expedition failed, the Antarctic had seized Shackleton’s imagination.

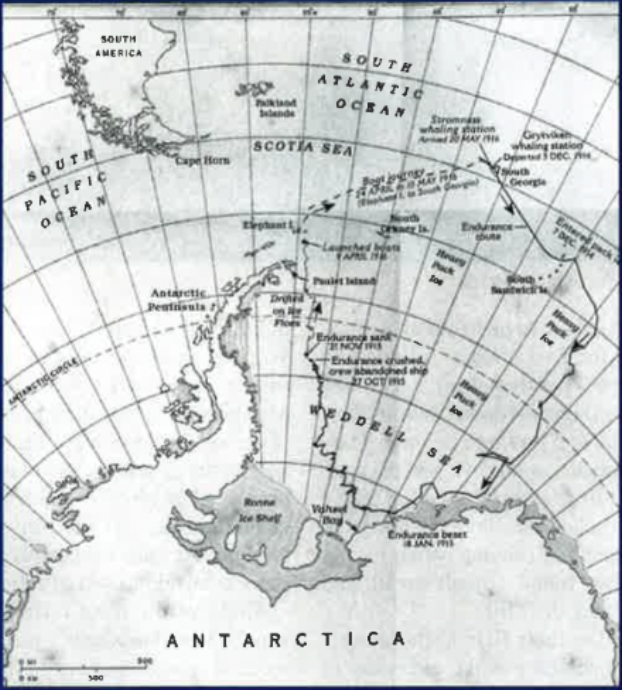

After his second failed attempt on the South Pole in 1907 and the subsequent success of Norway’s Roald Amundsen in reaching the Pole in 1911, Shackleton became determined to lead an expedition across the entire continent from the Weddell to the Ross Sea. He purchased a 300-ton wooden barquentine equipped with both a sail and coal-powered steam engine. Measuring 144 feet long, she had been painstakingly crafted to withstand ice, and sheathed in greenheart, a wood so tough it cannot be worked through conventional techniques. Shackleton christened the ship Endurance after his family motto Fortitudine Vincimus, “By Endurance We Conquer.” This would be her maiden voyage.

The Endurance set sail from England in August 1914. Its crew of twenty-seven men included sailors, scientists, the ship’s officers, an artist, and a photographer. Also on board were 69 Canadian sledding dogs and the carpenter’s cat, Mrs. Chippy.

Their last port of call before entering the Antarctic Circle was South Georgia Island, inhabited only on the eastern coast by Norwegians who staffed the three whaling stations there. The whalers informed the Endurance crew that the pack ice in the Weddell Sea was the worst in memory. Shackleton decided to remain in South Georgia for a month hoping that some of the ice would clear. By early December, conditions still had not improved, but Shackleton decided to take his chances knowing that any real attempt for the expedition had to begin before the Antarctic winter set in. He decided to sail east to try and avoid the worst of the pack ice. They hoped to make landfall at Vahsel Bay on the Antarctic continent.

Only two days into their journey, they encountered pack ice and spent the next six weeks dodging loose ice floes or ramming through them. However, on January 18, 1915, only a day away from Vahsel Bay, the Endurance became locked in the ice. Occasionally a lead of free water would appear close by and the crew would use chisels and crowbars to try and cut a path to it, but every attempt failed — the lead would close or the ice would be too thick to cut. After weeks of immobility, Shackleton and his crew had to accept that they were frozen for the duration of the coming Antarctic winter. The men entertained themselves by organizing football and hockey games on the ice, exercising the dogs, and having singsongs or listening to the phonograph in the evening. In early May the Antarctic night began, leaving the ice-locked Endurance to drift through the darkness further and further from land. Repeated attempts to make contact over the wireless failed. No one in the world knew where they were or if they were still alive.

To keep up the men’s spirits Shackleton imposed a strict routine. He also found reasons for celebration. Every Saturday evening all of the men would gather, a measure of grog would be doled out and they would all toast, “To our sweethearts and wives…may they never meet.” Through these long months of darkness, the crew remained relatively peaceful given their circumstances, due in large part to Shackleton’s own unwavering optimism and strong leadership.

When Shackleton finally ordered that the ship be abandoned, the three lifeboats, sleds, and provisions were lowered down to the ice where the men set up camp. The situation was dire. During their first night on the ice, they had to move three times because the floe underneath them cracked. As the ship’s captain Frank Worsley pointed out, “We had food only for four weeks. We had nothing to keep out the biting cold save linen tents, linen so thin that when there chanced to be a moon we could easily see it through the material. And we had to sleep on the ice, on a covering that was not water-proof, so that such warmth as there was in our bodies would melt the ice and cause us to lie in pools of water.”

The shifting pack continued to slowly grind the Endurance until on November 21, 1915, the crew watched as she slipped beneath the ice.

Rather than expend their energy hauling their supplies over the rough ice, Shackleton decided that they would remain where they were and let the drifting pack carry them westward toward land. Knowing the sea around them to be the most dangerous in the world, he postponed launching the lifeboats as long as possible. However, by April 9, the ice beneath them had disintegrated to such a degree that they were forced to launch the boats and throw themselves on the mercy of the tempestuous Weddell Sea.

Over the next seven days, the men battled the currents during the day and camped precariously on ice floes or tried to sleep in the open, waterlogged boats at night. Few found any sleep, and exhaustion only added to the physical and mental discomfort they suffered. Constant exposure to salt water caused their skin to erupt in painful boils. Most of the men suffered from seasickness and frostbite. After months of a diet lacking in carbohydrates, the men were weak and easily exhausted by the constant rowing. The trip was so arduous that it drove some of the men temporarily insane. Fear was a constant companion.

Finally, the mountains of Elephant Island loomed on the horizon. When the boats landed ashore, the men stumbled about aimlessly. Some simply lay down to feel the solid earth. It was the first time they had touched land in over a year.

Knowing that no one would ever look for them on this uninhabited island, Shackleton determined that their only hope of rescue would be if they could reach the whaling station on South Georgia Island some 800 miles away. The journey would entail sailing in a small twenty-two-foot-long boat across the most dangerous stretch of water in the world with winds that could reach up to 80 mph, frequent storms, and waves measuring 60 feet high.

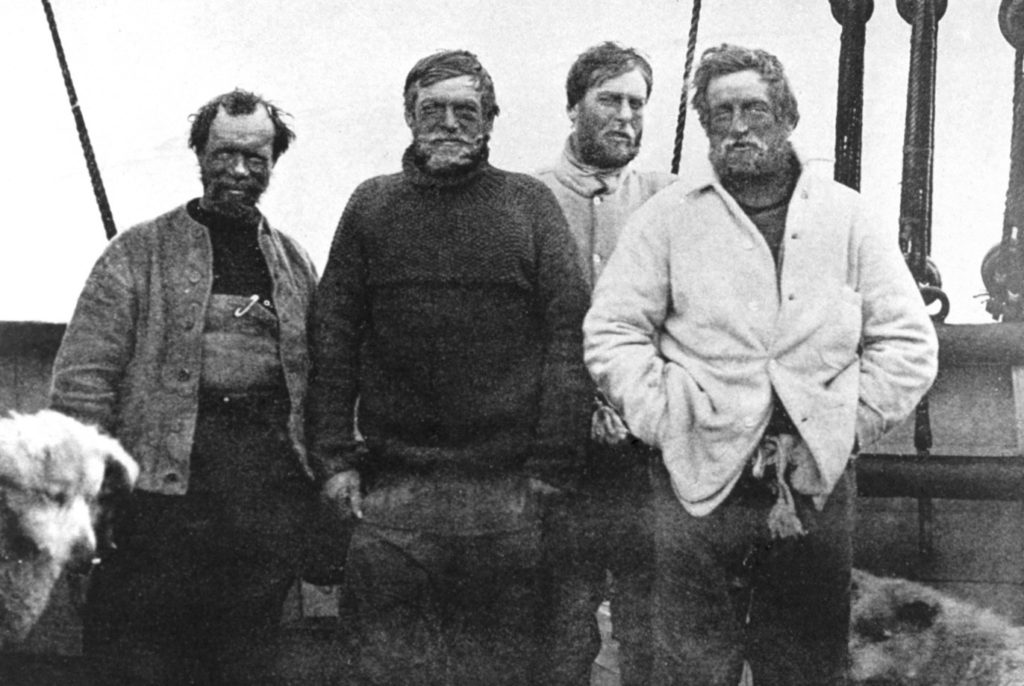

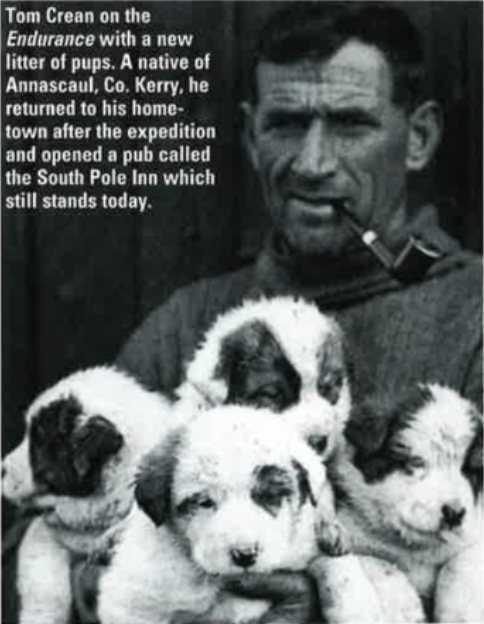

On Easter Monday, April 24, 1916 (the day the Easter Rising began in Dublin), the largest of the lifeboats, the James Caird, was launched carrying Shackleton, Captain Frank Worsley, Tom Crean, the carpenter Harry “Chippy” McNeish, Timothy McCarthy and John Vincent. McNeish and Vincent were the most troublesome of the entire crew. Knowing full well that demoralization posed as much threat to the crew’s survival as the elements, Shackleton undoubtedly knew that chances of survival would be greater for those remaining on Elephant Island if these two were not in their midst.

The James Caird made fairly good distance each day averaging 60 to 70 miles, but living conditions on the tiny boat were a nightmare. Sleeping bags became wet making it impossible to find any warmth. The sailors’ legs were chafed, swollen, and a sickly white from their wet clothing which hadn’t been changed for seven months. Exposed fingers and hands became blistered with frostbite. In the cramped boat, sleep was almost impossible to find.

The waves they encountered were so high that their sail went slack in the calm between the towering crests. Navigation was problematic at best. The only tools Worsley had were a sextant and a chronometer. Navigating by sextant requires a celestial sighting, but brooding skies allowed Worsley to take only four readings over two weeks. To take a reading he had to be held steady in the pitching boat by two men and try to guess where the horizon was on the roiling sea. If his reading was off by even one degree they could miss landfall and be lost in thousands of miles of ocean.

On April 30, they were hit with a southwesterly gale that brought with it freezing temperatures. Everything on the boat became covered with a coating of ice more than a foot thick in some places, and the boat began to ride dangerously low in the water. They chipped away at the ice and threw the spare oars and two of the frozen sleeping bags — each weighing close to forty pounds — overboard. At midnight of their eleventh day, Shackleton was at the helm when he noticed a line of clear sky. He shouted to the men that the gale was finally clearing. A moment later he realized that what he thought was a break in the clouds was really the crest of an enormous wave. The wave broke over them. Using any receptacle they could lay their hands on, the men bailed with all their might, and miraculously, their little boat survived.

The following day Worsley determined that they were only one hundred miles from South Georgia Island and anticipated landfall within two days. But now they had a new problem: they had run out of drinking water. They became so dehydrated their tongues swelled inside their mouths, their lips cracked and eating became painful.

Shortly after noon on May 8, McCarthy caught a glimpse of South Georgia Island. It was exactly two weeks since they had left Elephant Island.

Looking for a landing place, they encountered only submerged rocks, dangerous reefs, and sheer sea cliffs. Night was falling, and as thirsty and miserable as they were, they decided to wait until the following day to try and find a place to land. In the early hours of the morning, they were hit by a hurricane that drove them back out to sea. They later learned that a 500-ton steamer with a full crew had foundered in the same storm.

When the sun rose on May 10 they sighted an indentation in the rocks that they believed to be King Haakon Bay. Shackleton decided they would land here. However, the bay was surrounded by a jagged reef. They sailed for a small gap in the reef, but the wind drove them out of the bay. After five attempts tacking into the wind, they were able to sail through the small entrance of the reef and into the bay. They found a small cove, and the boat, riding a small swell, finally reached the shore. Hearing the sound of running water, the six men found a small stream and drank their fill.

On their first night ashore, Shackleton woke everyone in the middle of the night shouting, “Look out boys, look out! Hold on! It’s going to break on us.” He was having a nightmare about the huge wave that nearly capsized them. The journey of the James Caird, a miracle of navigation, seamanship, and endurance, is now regarded as one of the greatest boat journeys in history.

Their ordeal was far from over. Shackleton and his men were only 17 miles away from the Stromness whaling stations, but it entailed traveling over South Georgia’s unmapped mountains and glaciers, a feat never before accomplished. Not fit for further travel, McCarthy, McNeish, and Vincent remained at the camp until Shackleton and the others could have a boat sent for them. At 2 A.M. on Friday, May 19, with the light of the moon to guide them, Shackleton, Crean, and Worsley set out for the whaling station. They carried with them McNeish’s adze to cut steps out of the ice, 90 feet of rope, a compass, a small primus stove, and three days’ worth of food. Screws taken from the boat were driven through the soles of their worn shoes to provide traction on the ice.

Ahead of the three travelers was one of the island’s many mountain ranges made up of five peaks with spaces in between that they hoped might be passes. Worsley chose the pass on the right since it was the lowest and seemed the most direct route to Stromness. However, on reaching the top of the pass they saw only impassable terrain before them, steep precipices and sheer ice cliffs, giving way to a hazardous, glacier surface. They doubled back to try the other passes, but the second and third were no better than the first. The fourth pass was their last and only hope. Darkness was approaching, and they had been hiking, stopping only for meals, since 2 A.M. the night before.

Reaching the lowest part of the final pass, they found themselves on the brink of a giant chasm. Worried that a sudden gust would sweep them into this ravine, they hurried up to a higher part of the pass, cutting steps into the ice with the adze. They found themselves on the ridge of a razor back of ice. By now it was completely dark and fog had rolled up. In front of them was a steep slope, which they began to climb down, once again painstakingly cutting steps in the ice. The going was too slow, though. They had to reach the lower ground quickly, or else they would freeze to death in their exposed position. Shackleton determined that their only hope, indeed the entire Endurance crew’s only hope, would be for them to slide down the slope through the darkness and fog into unknown terrain and hope that no chasms or boulders lay in their path.

They coiled the rope to sit on, Shackleton sat in front and Worsley behind him with his legs and arms wrapped around Shackleton, and Crean wrapped around Worsley. Then Shackleton pushed off. According to Worsley: “We seemed to shoot off into space. For a moment my hair fairly stood on end. Then suddenly I felt a glow, and knew that I was grinning! I was actually enjoying it. It was most exhilarating. We were shooting down the side of an almost precipitous mountain at nearly a mile a minute. I yelled with excitement and found that Shackleton and Crean were yelling too. It seemed ridiculously safe. To hell with the rocks!”

When they finally came to a stop, they looked back at the mountain they had just sped down. In less than three minutes they had descended 1,500 feet.

Continuing onward, they came upon a slope down which they strode easily, only to find themselves among the impassable crevasses of a glacier. Knowing there was no glacier near Stromness Bay, they had to retrace their steps toiling back up the slope.

As the sun rose, the trio reached the top of another ridge of mountains and recognized below them the land around Stromness Bay. At seven o’clock they could hear across the clear, morning air the steam whistles of the whaling stations.

Reaching the top of the last ridge, they made their way down a ravine that became so steep and narrow they were forced to wade through the stream of water at the bottom. To their dismay, the ravine ended in a waterfall. Too tired to turn back, they decided to lower themselves on the rope down through the waterfall.

At three o’clock in the afternoon of May 20, they reached the Stromness whaling stations. They were exhausted and famished, having marched 36 hours straight, stopping only to eat from their meager supplies. The screws they had driven through the soles of their shoes were now completely worn down.

When the manager of the station, who had entertained them and the rest of the Endurance crew only two years before, met them he failed to recognize them. The world had long ago given up on Shackleton and his crew. When the whalers realized who he was, one of them turned away and cried. No one knew better than these men what the crew of the James Caird had just accomplished.

That evening a huge blizzard blew up in the mountain range the three travelers had just crossed. They later learned that they crossed the island during the only period of fine weather the island enjoyed that winter. And perhaps a little more than luck was with them during that fateful crossing. When Shackleton, Worsley, and Crean recalled their journey over South Georgia Island, they all said they felt the presence of a fourth person traveling with them.

While Worsley set out on a whaler to rescue the three men in King Haakon Sound, Shackleton made arrangements to journey back to Elephant Island. He chartered a British whaler and on May 23, he, Crean, and Worsley along with a crew of Norwegian volunteers from the whaling stations set out for Elephant Island.

Within a hundred miles of Elephant Island, they spotted pack ice that gradually grew more dense. Sixty miles away from the island they were forced to turn back; the whaler was no match for the ice that faced them. They traveled west, hoping to skirt the ice, but when their fuel reserves ran low were forced to land on the Falkland Islands. Shackleton paced the decks, turning to Worsley from time to time and asking, “They can’t be starving yet, can they?”

Upon landing at the Falklands, Shackleton sent a cable to King George of England, informing him of the loss of the Endurance and the plight of the crew on Elephant Island. However the British Navy were completely engaged in fighting World War I, and they informed Shackleton that they would not be able to provide him with a boat until October. After almost two weeks the government of Uruguay offered Shackleton the use of a trawler, and they departed the Falklands on June 10, at the height of the southern winter. The second and third attempts failed as both times the pack ice forced them to turn back. Shackleton was nearly heartbroken. He appealed to the Chilean government for assistance and they furnished him with a steamer, the Yelcho.

As the boat drew close to Elephant Island, it was enveloped in a thick fog that forced them to slow down in order to negotiate submerged rocks near the coast. Gradually, familiar aspects of the shoreline came into view as they approached the camp. As Worsley steered the boat, Shackleton stared intently through his binoculars. Worsley recalled:

“I heard him [Shackleton] say in a low strained voice:

`There are only two, Skipper!’ Then, `No, four!’ A short pause followed and he exclaimed, `I see six — eight –‘ and at last in a voice ringing with joy, he cried, `They are all there! Every one of them! They are all saved!'”

It was 1 P.M. on August 30, 1916. It had been 128 days since the James Caird left Elephant Island, days spanning the harshest of the Antarctic winter. Upon reaching Punta Arenas, Shackleton wrote to his wife, “I have done it. Damn the admiralty…. Not a life lost and we have been through Hell.”

Apart from the drama of this survival epic, the story of the Endurance crew’s survival remains compelling because it hinged on the leadership of one man, who accomplished what should have been impossible to bring these men home. Even though every expedition he undertook ultimately failed in attaining its goal, Shackleton’s astute understanding of human nature and leadership abilities elevated him from merely human to heroic. One oft-quoted tribute to Shackleton goes, “For scientific leadership give me Scott; for swift and efficient travel, Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when there seems no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.”

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton died of a heart attack on January 5, 1922. Appropriately, he was back on South Georgia Island, leading another expedition to Antarctica. Once again, Wild, Worsley, and several other members of the Endurance crew were with him, a testament to the fierce loyalty he inspired. When the men tried to arrange to have his body returned to England, Shackleton’s wife wrote to them that he should be buried in South Georgia, and as Worsley observed, “I do not think he would have wished a different grave. He lies in a spot that for more than a hundred years has been the last home of seamen — whalers, sealers, and explorers — a spot swept by the elements among which so much of his life was spent, and facing the great white spaces which forever called to him.”

Note: This article was first published in our June/July 2000 issue.

Editor’s Note: The wreck of Endurance was found on March 5, 2022, at a depth of 9,869 feet and approximately four miles south of Worsley’s original calculated location.

This issue was originally published in the June / July 2000 issue of Irish America.

To the irishamerica.com owner, Thanks for the well-researched and well-written post!

To the irishamerica.com webmaster, Thanks for the well-researched and well-written post!

Wonderful post, I really enjoyed reading it. The way you write is captivating, and the information you provided is extremely helpful.

I will definitely bookmark it with my friends and return for more.

Thanks for posting this!

I every time spent my half an hour to read this web site’s posts all the time along with

a mug of coffee.

“Endurance” is the word that truly captures the brilliance of Captain’ Shackleton’s leadership. Reading this astonishing piece of history gives me hope that humanity will survive the fearful challenges our world throws in our paths today.

Thank you writer Sarah Buscher and Irish America for publishing and posting. A must read and save,

One of the highlights of our family trip to Ireland was listening to our guide regale us with the harrowing tale of the Endurance voyage and end the story with a stop at Tom Crean’s South Pole Inn to toast Shackleton, Crean and the crew for their heroism. Clearly, divine providence aided Shackleton’s determinism. It was truly a miraculous endeavor.

Another great story from Irish America. I spent some time working on a vessel in Antarctica and also spent a few days in the Island of South Georgia. In light of same, I was already familar with the history in the article but have to state the article is excellently written.