“The question before the House, in view of the apathy, neglect, and lack of understanding, which in this House has shown to these people in Ulster, whom it claims to represent, is how in the shortest space it can make up for fifty years of neglect, apathy, and a lack of understanding…”

“If British troops are sent in, I should not like to be either the mother or sister of an unfortunate soldier stationed there.”

– Maiden Speech by Bernadette Devlin,

House of Commons, April 22, 1969

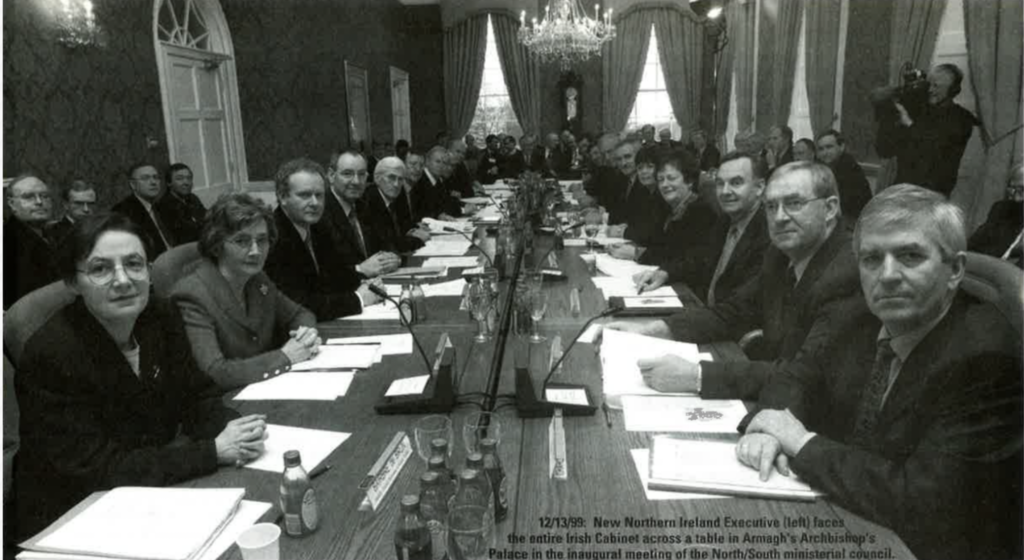

As David Trimble, Unionist First Minister, delivered a speech to mark the historic opening of Northern Ireland’s new Parliament, a heckler caused him to falter. But his Deputy First Minister, the Nationalist Seamus Mallon, bolstered him in symbolic fashion: “Keep going,” he snapped. Trimble recovered and the protester was swept away.

The incident capped a day that had begun with another appropriate vignette. I had looked out my window to discover that a large rat had made its way up through a thorn bush, along a very thin, swaying branch, and was vainly attempting to eat birds’ peanuts protected by a wire cylinder.

It was an apt piece of symbolism for the activities of the anti-Good Friday Agreement Unionists, chiefly those of Dr. Ian Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party.

Paisley’s party took no part in the deliberations which led to the setting up of the Assembly, beyond doing everything it could to abort them, yet under the provisions governing the Assembly’s workings, the DUP has two ministers in the new cabinet. Though they draw their £70,000 salaries, neither turned up at the historic first meeting of the Assembly on December 2, in protest of Sinn Féin’s presence.

The good news, however, is that, while the DUP’s propensity for destruction (and that of some dissident members of David Trimble’s own Ulster Unionist Party) should not be underestimated, the reality of the Assembly’s composition is that of its 108 seats, only 28 went to anti-Agreement parties. (Apart from the DUP, these consist of the tiny United Kingdom Unionist Party, led by an uncharismatic lawyer, Bob McCartney, and a clutch of independents.)

Although the other parties, whether Nationalist or Unionist, are divided on practically every issue, they are united in the promise of implementing the Good Friday Agreement.

In the June 25, 1998 Assembly elections, they got a mandate to do what they are only now doing: set up a power-sharing executive, establish cross-border institutions to improve cooperation with Dublin, and create similar bodies to improve outreach to the U.K. In turn the Dublin Government would give up the Republic’s claim, as laid out in Articles 2 &3 of the Irish constitution, to Northern Ireland. (This area is often erroneously referred to as “Ulster,” but in fact at the state’s inception in 1920, the Unionists refused to take control of the entire nine counties of Ulster, because they feared that this would bring so many Catholics into the fold that the Protestant Unionists would eventually be outnumbered.)

Can the new arrangements enable the new Assembly to control the existing six-county area? Will the Unionists in fact be ultimately outnumbered?

The answer to both questions would appear to be yes. Even in the archaic structures of Unionism, in the powerful Orange order, the will of the people expressed in the June 1998 elections was for peace, built on the IRA’s ceasefire.

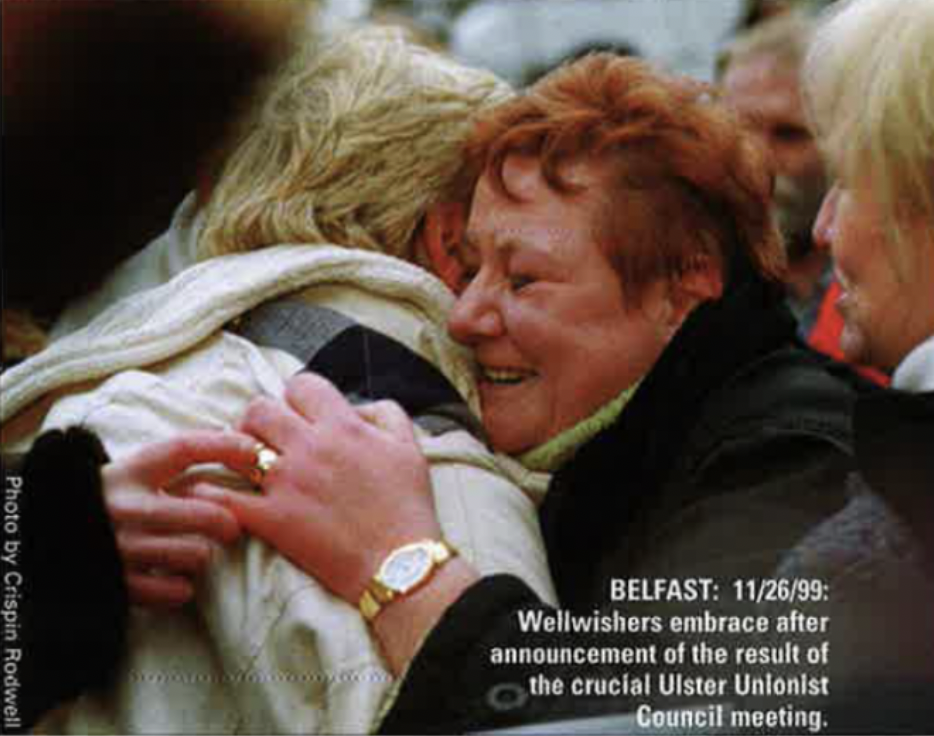

Granted that the fudged compromises over the issue of IRA arms decommissioning, which enabled David Trimble to get the go-ahead from his ruling Unionist Council to go into government with Sinn Féin, has some nasty trip wires built into it, which could cause damage later. Nevertheless, the decisive vote was 480 to 349 in favor.

The Unionist vote constitutes a considerably stronger mandate than the 64 to 57 majority with which the Anglo-Irish Treaty was voted into existence in January 1922. (I am old enough to remember the residual bitterness of the Civil War and its blighting effect on Irish politics. It was far more venomous than anything we now see in Northern Ireland.) But that treaty laid the foundations for the setting up of today’s booming Irish economy. What has occurred in the Irish Republic may also occur in the North.

Apart from Trimble’s majority in the Unionist Council, and the overwhelming desire for peace (on the part of the business community in particular), the new Assembly has powerful friends, the caliber of which was not available to the pro-Treatyites back in 1922.

There is firstly, the Irish American Lobby to whom history will indeed be kind. People like President Clinton, George Mitchell, Ted Kennedy, Jean Kennedy Smith, Niall O’Dowd, Bruce Morrison, Chuck Feeney, Bill Flynn, and before them, Paul O’Dwyer and Eoin McKiernan, will be remembered for the manner in which they validated the dream of the early Irish nationalists.

Other forces to whom we may reasonably look to, to keep the dream alive, are the Labour government of Tony Blair (which, unlike the former Conservative administration, is completely independent of the Unionist MPs at Westminster), the European Community, and the support and encouragement of the Dublin government, and the Irish people. The dropping of Articles 2 &3, and the generous vision of what constitutes Irishness which has replaced them, illustrates that the whole intellectual climate of the Irish Republic is more open, better educated, less absolutist and more willing to cut a deal than at any other time in Northern Ireland’s history.

The peace process has its enemies, of course – on the wilder shores of Unionism and Republicanism, in the Colonial cringers of Dublin 4 (Dubliners of an Anglophilic bent), and in parts of the British establishment. As Hugo Young, writing in The Guardian (December 2, 1999), rightly pointed out, there are those who want to see not only the Irish peace process fail, but the whole European experiment of cooperation. Young wrote with candor and courage, traits which, sadly, were more common amongst English journalists than Irish ones during the Troubles:

“Today’s installation of a devolved government in Belfast,” Young wrote, “is a triumph for politics, proof that reason can, ultimately and in the right circumstances and after bloodshed and beatings and blind doctrinal may-hem, begin to prevail. To the British nationalist, this is an abomination. The Telegraph worked for months to stop it happening, directing shafts of poison into every muscle of the peace process.”

The Telegraph was not alone. What about the [Irish] Sunday Independent’s Conor Cruise O’Brien, Ruth Dudley Edwards and Eoin Harris? These and many others must cower now before the lash of history.

The promise wrung out of David Trimble by opponents of the Good Friday Agreement, that he would reconvene the Unionist Council next February and wind up the new Assembly if by that time the IRA had not decommissioned arms, could cause the most damage.

The Good Friday Agreement provided for decommissioning as part of a general package of reforms introduced under the terms of the Agreement. These, apart from the establishment of a Parliament and cross-border bodies, included still-awaited reform of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (the police force) and the introduction of equality legislation.

However, until November 27, when the Unionist Council accepted its fudge, the entire Agreement was hung up on Unionist insistence that the IRA must decommission before Sinn Féin was allowed into government.

Over a year of precious time was allowed to elapse in which, paralyzed by fear of dissidents in his own party and the grip on Unionist politics exercised by Paisley, Trimble allowed the whole peace process to drift perilously close to the rocks of breakdown.

It took the return of the American, former Senator George Mitchell, who had brokered the Good Friday Agreement, to enable things to move ahead. Somehow over a period of 10 weeks of patient, private, media-free negotiation presided over by Mitchell, the Good Friday Agreement was put back together again, and the installation of a Parliament in Belfast on December 2 was the result.

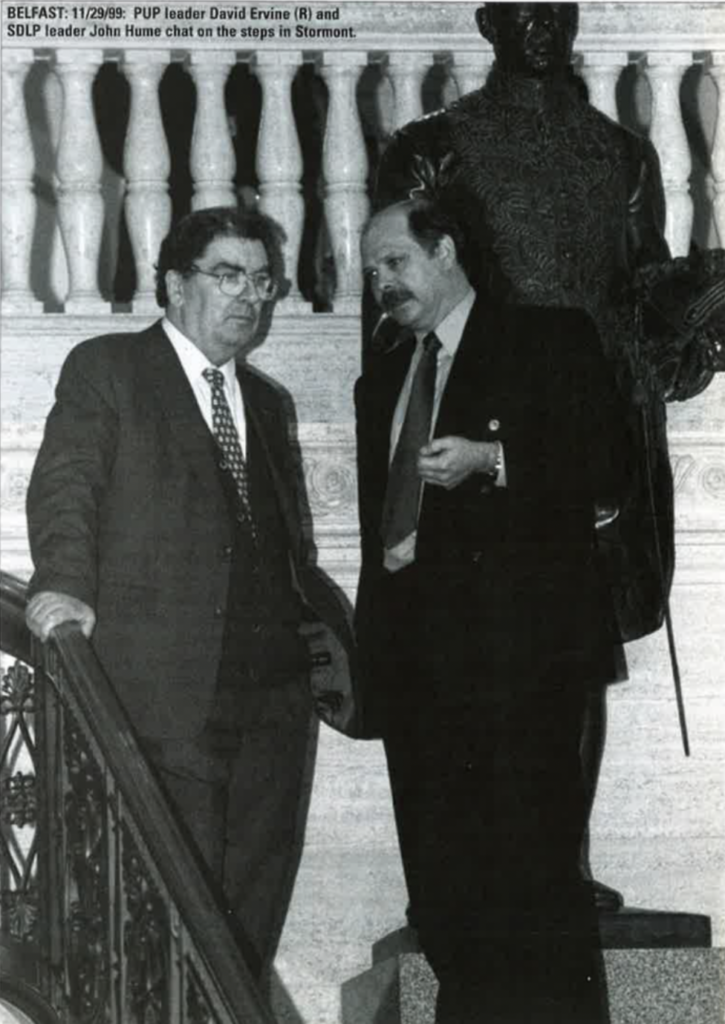

The way to the setup of the Parliament lay through a set of four pre-agreed statements issued by the major players in the Northern drama: Mitchell himself, David Trimble, SDLP leader John Hume, Gerry Adams and the IRA.

Unprecedentedly, the Unionist negotiators actually met with the IRA to satisfy themselves of the movement’s bona fides. When the statements were finally issued, David Trimble’s proved to be light years ahead of the hope-dashing diatribe he delivered at the ceremony in Stockholm in December 1998 at which, with John Hume, he received a Nobel Peace Prize.

On that occasion, his use of Cold War language and his ascription of fascism to Sinn Féin appeared to make his Nobel laureateship the most inappropriate accolade since Caligula made his horse a Consul. However, one year later, under Mitchell’s tutelage (and face-to-face contact with his Sinn Féin adversaries), the most recent Trimble statement proved to be a statesmanlike, forward-looking document which spoke of respecting all the traditions of Northern Ireland, leaving the past behind, and building a secure and prosperous future for all.

At the moment, that vision appears capable of fulfillment. The will of the majority of the people is being heard above the roars of the dinosaurs on the Paisleyite wing of Northern Ireland politics.

It is true the IRA’s anger over losing more than a year and a half since the Good Friday Agreement’s initial signing could yet make the Unionist fudge inedible.

But it’s not so long ago since David Trimble was saying that the Unionists would not even negotiate with Sinn Féin until all the IRA arms were handed in, and Martin McGuinness, on behalf of the Republicans, was saying that there wasn’t “a snowball’s chance in hell” of the IRA ever agreeing to decommission and risk the appearance of surrendering.

Now Martin McGuinness is a Minister for Education in a cabinet led by David Trimble, and thinking Unionists know that the accelerating Catholic birth rate has changed forever the classical formula that the six counties were two-thirds Protestant to one-third Catholic. Past census taking was distorted, because the IRA kept census enumerators out of Catholic districts, fearing intelligence gathering. But independent demographers believe that the next census, due in the year 2001, will show that the cultural Catholic, or Nationalist, population will have risen to close to 46 percent.

the result of a crucial Ulster Unionist Council meeting.

The Unionist vote has dropped to a level of only 50 percent of the electorate (as of June 1998) and is expected to continue to decline, because the majority of new voters coming on the register since 1994 have been Nationalist, and 35 percent of the largest Protestant sect, the Presbyterians, are over 75.

Some observers speculate that there will be a Nationalist majority at the time of the 2010 census.

Either way, despite the presence of dissident Republicans hovering in the wings, seeking to make the decommissioning issue a pretext for a return to war, it does seem as if the rat will not get at the birdfeed.

For, while the Unionists were concentrating on the decommissioning issue, the pragmatic Nationalist politicians kept their eyes on the money and on the realities of contemporary politics. The Nationalists nominated two women ministers, Bairbre de Brain and Brigid Rogers. The two Sinn Féin ministers emerged from the share-out in control of half of the Assembly’s budget, and Mark Durkan of the Nationalist SDLP got elected Minister for Finance.

For too long, the close of a century in Ireland has been marked either by the ending of a bloody revolution or the sowing of the seeds of one. As the 17th century was ending, the Orangemen were beating their drums in triumph over 1690, when William of Orange defeated James II, a Catholic, at the Battle of the Boyne. 1800 was ushered in to the shrieks of 1798, and the debate over the fateful Act of Union. 1900 saw a Celtic Dawn Land Reform – and the sowing of the seeds of 1916, the Anglo-Irish War, Civil War, partition, and the thirty years of conflict in Northern Ireland, which have now ceased.

Will the cessation endure? Will the ending of the 20th century and the opening of a new millennium be different? I believe so. To paraphrase the Deputy First Minister Seamus Mallon, the forces of peace will “keep going.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the February / March 2000 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply