Our house had several windows, and most were wide open, inviting in the first smells of spring. It was the kind of day where I would normally be outside, soaking up the sun. But this nap had been planned over all the previous nights that I had been up late studying for my exams.

As I pulled up the covers and nestled in, there was a tap at the door, my mom stood at the bottom of the bed and asked, “Do you want to meet her?”

“Ma you know I do,” I said with a degree of certainty.

“Well, they found her, and she wants to meet you too,” she replied, her voice uncertain.

From the time I discovered I was adopted I had wanted to meet my birth mother. In my imagination, she was many things, but she was always an unwed young woman who “gotten into trouble.”

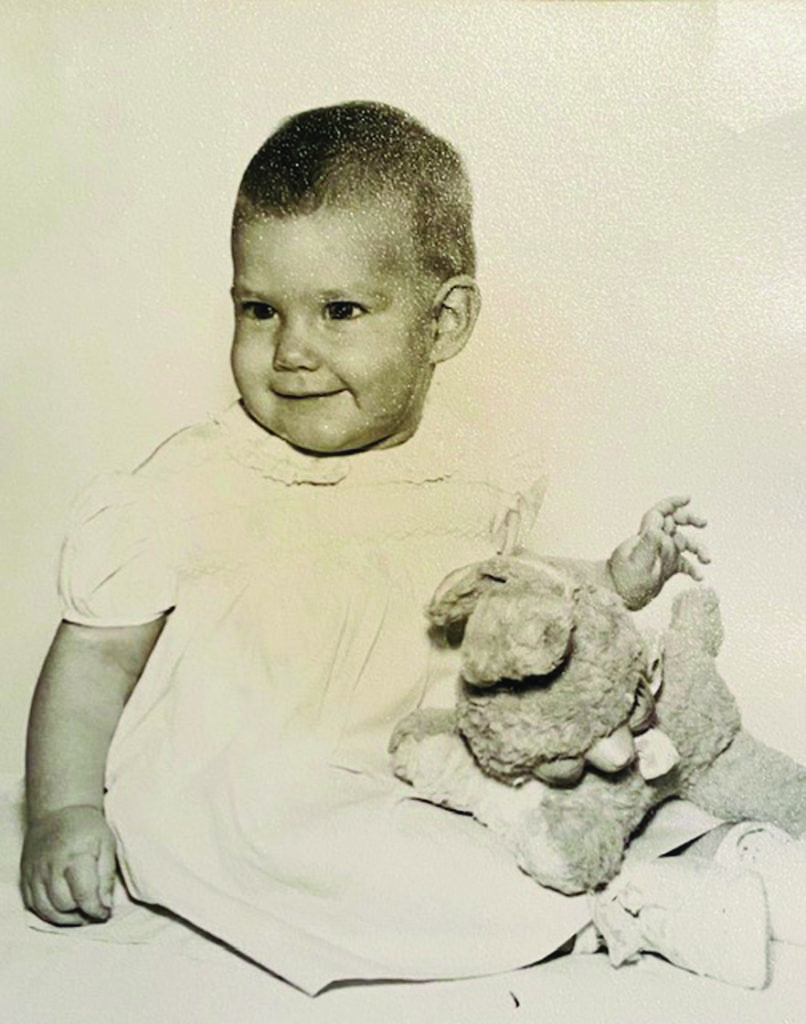

I was born on a snowy March day in Philadelphia and spent four months in a Catholic orphanage before being placed with a family: a mom and dad and an older sister. A younger sister would arrive a few years later.

Whoever had made the decision to place me with this family, gave me the greatest gift. My parents raised me to believe that anything was possible as long as it didn’t involve taking any risks. Their game plan for life was work hard, be content with what you have, stay humble, and play it safe.

When I accepted a position with a major Wall Street firm that would double my income and expand my professional network but would require me to relocate to another state, my Dad’s first reaction was to ask me in the gravest of tones whether I had been fired from my job. After a few attempts at convincing him of my accomplishment at landing this job he wrapped up the discussion by saying “Ok, but we don’t have to tell your mom if you got fired and that’s why you are moving away. And no matter what, we will always love you.”

My parents couldn’t fathom leaving a perfectly “good” job for another, especially if you had to move away to do it. They always played it safe, except for that one time when they were contacted about an infant girl being available. The nun who called explained that they would like to place the child in a home immediately with the understanding that there could be a recall as the birth mother had not signed the papers, and might not follow through with the adoption.

My would-be parents stepped out of their comfort zone and drove to St. Vincent’s to claim me.

My devout mom believed that God would not be pulling a bait and switch. I would be their Anne and that would be that.

She was born in March 1959 and spent her first months at St. Vincent’s Orphanage.

And that’s the way it turned out.

I came to learn later was that my given name was Patricia Mary. This became one of the facts I would use to build my fantasy story of my “Irish birth mother on.” And now I was going to meet her for real.

What does one wear to meet their mother? I played it safe, and was a vision in khaki.

My parents and I were quiet on the drive to the meet up on the appointed it. In the back seat of that Chevy Malibu I felt as close to them as I ever had as I tried to send strong silent messages that I was never more proud to be their daughter.

We were greeted by the social worker, a tall young woman. She explained that she would walk me down the hallway and I would be introduced to my birth mother who would be waiting behind Door # 2. Her name was Bridget (central casting had sent an honest-to-God Irish woman?). My parents would wait for me in a conference room, and we could decide later if they would meet her too.

The social worker was about 6-foot-tall and at 5’9” myself, I was impressed at her bearing and confidence as I followed her down the hall. She tapped quietly on a door, and slowly opened it.

I had to wait for her to step aside before I could enter, and then I saw a small figure – no more than 4’8’’– with her back to us. For a moment, I thought that we had entered the wrong room. Then she turned around to look at us, and I saw myself in her face. I moved across the room and we embraced.

In her Irish brogue, she said, “I thought you’d be a nun.”

I replied, “I thought you’d be taller!”

(I often wondered out I might have turned out had I been raised by someone who thought I might be a nun!)

I quickly determined that Bridget was religious and I began calculating how to cover the fact that I was no longer a regular churchgoer. I provided details of receiving the big C sacraments – Confession, Communion, and Confirmation – to establish my bona fide credentials and to cover for my parents who had committed to raising me as a Catholic as a condition of my adoption.

Time was limited that day, and after tackling religion, I began scratching the surface of the million questions I had been compiling for the past decade.

Now that the big moment was here, all that mental preparation had failed to account for one big factor. The fact that, for the first time in my life, I looked like someone else. I was mesmerized by my birth mother’s features and her hands, eyes, hair, and her smile.

Over the years, we saw each other twice a year in the summer and around the Christmas holidays. Our visits were cordial and pleasant. I offered updates on my life, like it was an annual performance review and my accomplishments were meant to honor my birth mother’s heroic and altruistic decision to give me a chance at a better life. Her reporting was much more concise, offering little detail and mainly focused on the present, avoiding the past, where I wanted to spend our time.

As the years passed, the visits dwindled, and our interactions were reduced to the obligatory Christmas card, but I savored the scant details that were shared. These weren’t favorite family stories repeated over the years and passed down through the generations. This was one person’s deepest secret and I always sensed her discomfort and unease when my questions got too close for comfort.

Meeting my birth mother did not reveal answers to the questions I had been carrying around for most of my life. But it did give me a better appreciation for the parents who raised me and all that they had given to me. Their “play it safe” strategy wasn’t to hold me back but to keep me safe until I went out on my own. Being content with what I had was to keep me grounded so that material success wouldn’t replace humility.

The reward for hitting the adoptive parents’ lottery was encouragement to live life with a sense of optimism – and the knowledge that anything is possible. Not having a family medical history meant that I was unencumbered by the knowledge that I might contract some hereditary disease. As it turned out on most days, I forget altogether that I was adopted because my parents did such a good job of making me part of their family history.

Great story. Awesome to meet your birth mother. As a pro-life activist , I am very proud of your birth mother. As a relative , I certainly know your adoptive parents were truly special .