“The first things they found were buttons, and then they found pieces of artifacts like clay pipes which they figured were from the people who were doing the burials. Then they found the bones – four children, three teenagers, and seven adults,” recalls Victor Boyle.

The bones were unearthed in 2019, when the Canadian railway system began digging about the Black Stone Monument to install pylon support pillars for their trains.

That’s when Boyle and other Irish Canadian organizations stepped in to prevent the desecration of the last resting place of thousands of Irish who died fleeing starvation in their own country and are buried beneath the site.

Boyle is the president of the Montreal Irish Monument Park Foundation and Canada’s A.O.H., but his devotion to preserving the Black Stone Monument and the memory of those who died, goes back to when he was a child. His grandfather would point to the Rock as they crossed the Victoria Bridge in Montreal and say, “Do you see that stone? That’s yours. And don’t ever forget. Don’t let anybody forget it.”

1847 was the worst year of the Great Hunger in Ireland. The Agnes arrived from Ireland to Canada on May 27, 1847, with 427 passengers aboard. In just 15 days, only 150 people were still alive.

The story was the same for many on the ships that lined the St. Lawrence River that year waiting to disembark on Grosse Île.

The fever sheds on the quarantine island were overcrowded and over half of the Irish, who were deemed healthy enough to leave, died within weeks and are buried all along the St. Charles River, while on Grosse Île itself, thousands more are buried in mass graves.

The Black Stone Monument dates back to 1859 when workers building the Victoria Bridge came across some of the bodies and used a large rock they had pulled from the river to mark the spot.

In 1901 the Grand Trunk Railway moved the stone to advance its rail lines. In the following years the Irish in Montreal fought many battles with the city to ensure that the Black Stone monument remained in place.

As it stands now, the site is located between two busy roadways and an industrial area.

In 2019, the current railway system, Résau Express Métropolitain (REM), proved more willing to preserve the sacred site than previous transit systems.

“The railroad company redesigned its overhead span at the cost of $50 million to make sure that only one pylon needed to go into the cemetery,” Boyle explained. “They were as dedicated to protecting the sanctity of that cemetery as we were.”

“And that pylon was in the southwestern most part of the cemetery, so they were hoping to miss bodies completely. Of course, they didn’t; they discovered fourteen.”

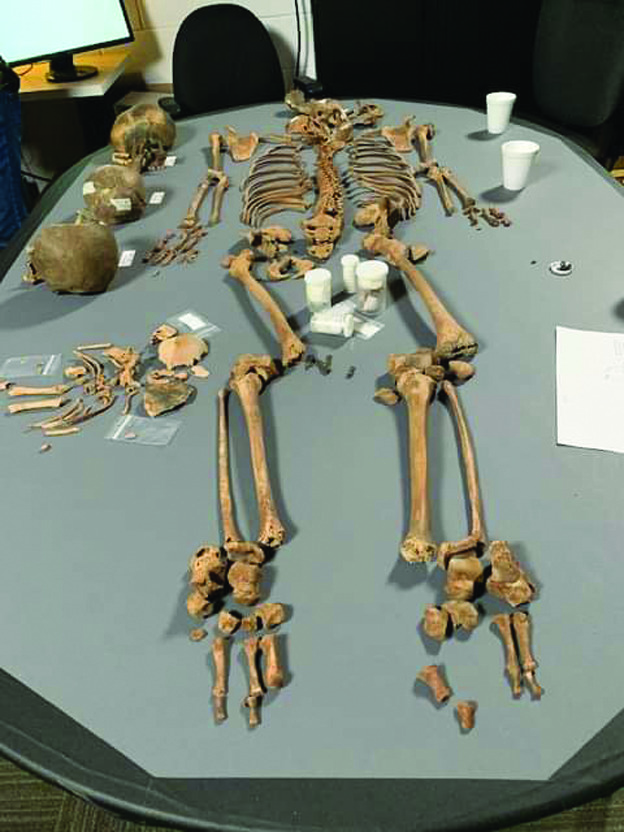

Archaeologists carefully excavated the bones and reassembled the bodies. After two years of analysis, scientists presented the findings to the Irish community in Montreal.

The bones showed signs of malnutrition and diet deficiencies like iron as well as notable lead levels.

“Fractures, bacterial infections, chronic diseases and signs of malnutrition provide a window into the lives of Irish migrants in the mid- 1800s,” Marine Puech, a bioarchaeologist at the Ethnoscop lab in Boucherville, Quebec, who identified the remains, wrote in her report.

Puech went further into her analysis in a report on CBC, saying that the lab was able

to pinpoint the times of death to between August and September of 1847, and further, that almost all of the remains were of people from rural southwestern Ireland.

“It’s incredible,” said Boyle, who was able to visit the lab and see the bones being assembled into bodies, where they were identified by age and sex. “It really humanizes them; quite literally, it shows they are not just a statistic. It is a story of human disease, and poor nutrition, and migration.”

Boyle is hopeful that the 14 who were uncovered will one day be claimed by relatives.

He points to the fact that there are now 100 billion DNA samples in an international database that can provide context to the migrants’ stories and food intake and possibly, at some point, they can be reconnected to family.

Now that the construction around Black Rock has ended, Boyle’s next move with the Ancient Order of Hibernians is to expand the memorial site.

Plans include adding a cascading waterfall, an outdoor theater, and a small rock formation in circles where visitors can sit and reflect. He also wants to make sure that those who helped the destitute and desperate Irish are remembered. That includes Montreal’s French and Jewish communities, Mohawk and Choctaw Nations, off-duty British soldiers, and the Mayor of Montreal, John Easton Mills – all who mobilized en-masse to support the sick and dying Irish by sharing crops, providing clothing, and adopting orphaned children.

“We would like people to spend time there because the park, the memorial, when it’s done, will be a beacon even in modern times,” he says. He hopes that it will move people to have empathy for today’s refugees.

In the meantime, Victor Boyle will continue the annual A.O.H. “Walk to the Black Rock,” where hundreds of people march to the memorial stone on the last Sunday in May to commemorate the life and tribulations of those who survived their passage to Canada only to die in a short while. He will, of course, have his grandson Cian in tow.

Leave a Reply