The legacy of the statesman known as “The Liberator”, is explored over a two-day ‘school’ in his home place in Kerry.

Cahersiveen, County Kerry. Population, 1041: Famous because it is the furthest point from Dublin – traveling westwards, the next parish is New York. Despite its remote location, it is a town steeped in history and surrounded by rugged beauty. And, since the 1980s, it has been home to the annual O’Connell School that has the power to attract scholars, politicians, journalists, public intellectuals, descendants of O’Connell, sports men and women and local historians – anybody who has something to say and to share, for a two-day event that is as intense as it is exhilarating.

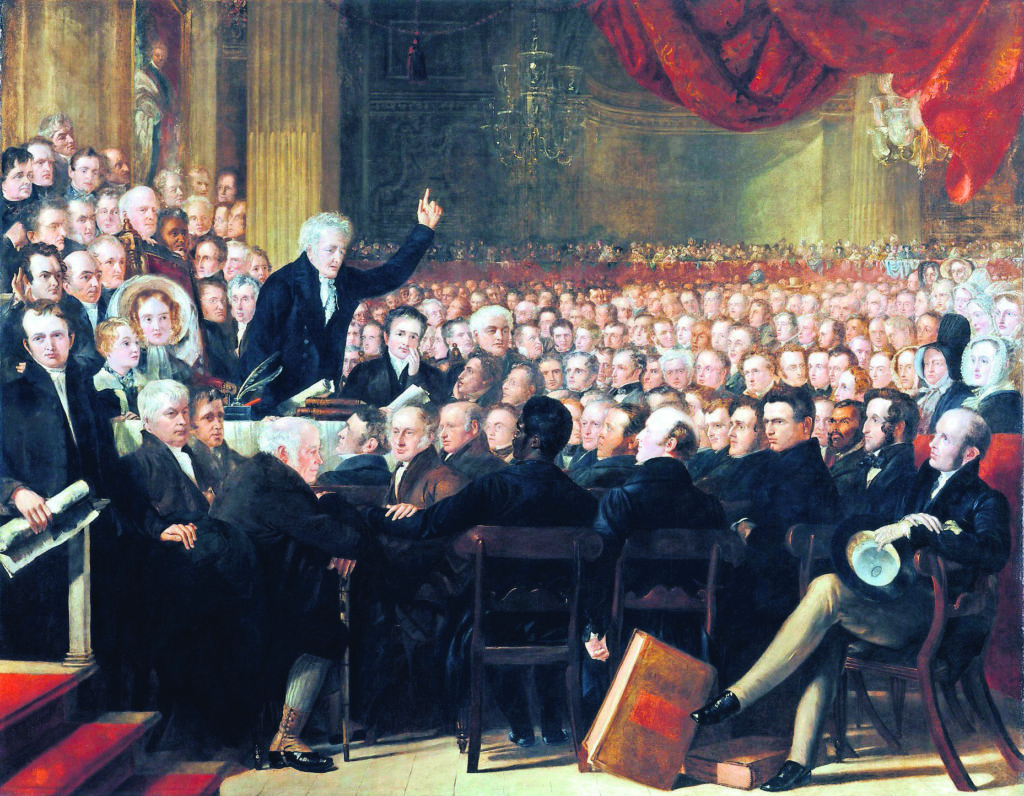

This year, it was held on October 28-29, and I had the honor to be invited to talk about my research on Daniel O’Connell and his role at the first International Anti-Slavery Convention, held in London in 1840.

Originally named the Daniel O’Connell Heritage Summer School, it was first held in the 1980s and revived in 2013. During the COVID pandemic, it continued by embracing the powers of Zoom and livestreaming. The 2022 School was held in person, but it was also possible to watch it online. Unlike other Schools, the Daniel O’Connell School does not deal with a specific theme. “We offer a mix of lectures which deal with aspects of O’Connell’s career and how these influence life in modern Ireland,” the school’s academic director, Professor Maurice Bric explained.

The diversity of topics makes for many lively discussions both during the formal sessions and over coffee, lunch, breakfast and dinner. And even if Daniel O’Connell is not the direct focus of many papers, his presence is palpable everywhere.

O’Connell was born in Carahan, just outside Cahersiveen in 1775, at a time when Catholics were discriminated against socially, economically, culturally and politically. O’Connell used his incredible talents as an orator and talented lawyer to win back one of the final obstacles to Catholic equality, namely, Catholic “Emancipation.”

In 1829, he successfully forced the British government to allow Catholics to sit as lawmakers in the Westminster Parliament (which then governed the whole of the United Kingdom of Britain and Ireland). In keeping with his hatred of violence, O’Connell only ever used peaceful and constitutional methods. For his role in winning Catholic Emancipation he became known as “the Liberator.”

More than this though, O’Connell was also a champion of oppressed people everywhere: Jews, Maoris, Aborigines, and the enslaved. Poignantly, his final speech in the British parliament, on 8 February 1847, when he was sick and dying, was on behalf of the victims of the Great Hunger – he begged his fellow parliamentarians to do more to stop the suffering of the Irish poor. His appeal fell on deaf ears. Only three months later, O’Connell was dead.

The format of the School is that the first day is held in Cahersiveen, while day two is held in O’Connell’s beautiful home in Derrynane. In between, there is great company and great craic to be enjoyed. And the local food and hospitality are amazing. The scenery, whatever the weather, is stunning.

My colleague, Bob Young and I, together with several of the other speakers, stayed at Sea Breeze – a fantastic Bed and Breakfast, hosted by Ailísh and Tom, who could not have been more welcoming. Interestingly, we stayed there because the largest hotel in the town, the Ring of Kerry, is now home to Ukrainian refugees. So far, this mass community has welcomed as many as 400 refugees.

The program of this year’s School was diverse and each talk was fascinating. On the first day, topics included, The Irish Civil War in an international context; The evolving role of Seanad Éireann since 1922; The private and public life of a First Lady in 1920s Ireland; Ada English: a patriot and psychiatrist in search of mental illness; the Spanish Flu of 1918-1919 and how it shaped public policy and healthcare in Ireland, and a talk by Mickey “Ned” O’Sullivan, legend of the Kerry Gaelic Athletic Association.

We even had a lunchtime visit from local storyteller, Sean (an Seanchaí) O’Laoghaire.

The talks were limited to 20 minutes, which resulted in high-energy, lively and focused presentations. An exception to the 20 minute rule, and a highlight of day one, was an informal chat with Bertie Ahern, who served as Taoiseach between 1997 and 2008 and is widely regarded as one of the main architects of the Good Friday Agreement. He was interviewed by Stephen Collins of the Irish Times. When asked if he was planning to run in the election for President in 2025, as a successor to the brilliant Michael D. Higgins, Bertie was elusive but didn’t rule it out.

the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1880.

Day two took us to O’Connell’s ancestral home, Derrynane House in Caherdaniel (Teach Dhoire Fhionáin). It is situated in one of the most stunning locations in Ireland. The drive from Caherciveen, over rugged mountain terrain, was breathtaking. An unlooked-for pit stop was to see the statute of Charlie Chaplin in Waterville, his favorite holiday destination. Chaplin has his back to Valentia Island, home to the first transatlantic telegraphic cable. Quite literally, because of this cable, south County Kerry became the center of the world’s communication network in the nineteenth century.

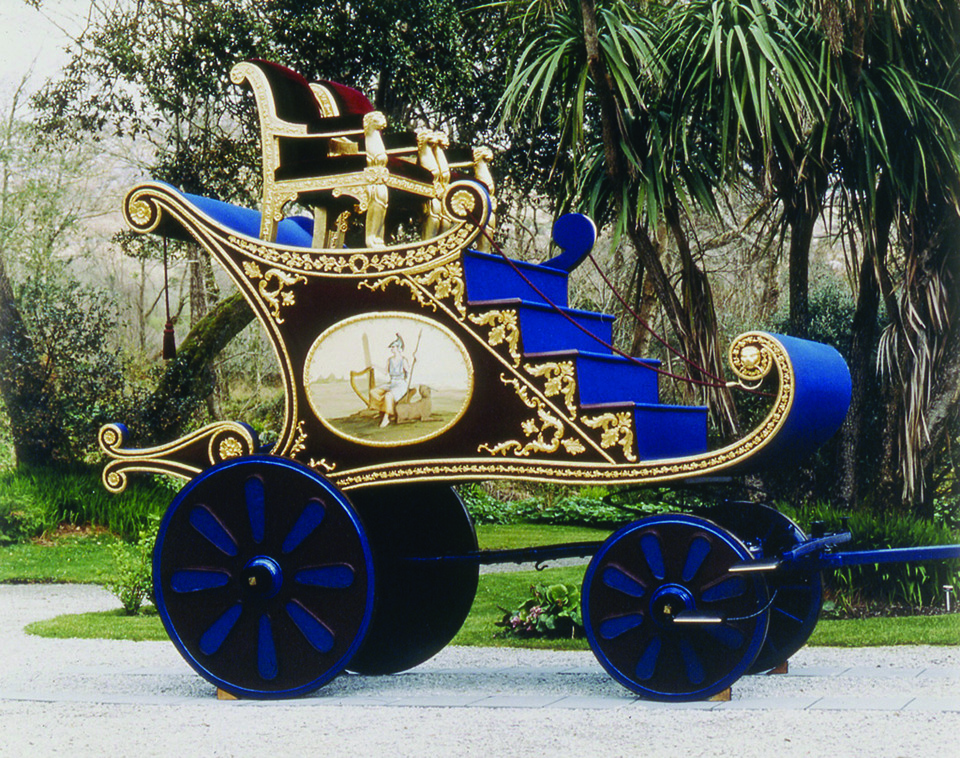

The lectures took place in the chapel at Derrynane House, which had been added in 1844 by O’Connell as gratitude for his release from prison in Dublin. It was modeled on the ruined monastery chapel of Derrynane Abbey on nearby Abbey Island. Throughout the day and between lectures, it was possible to tour O’Connell’s home. The bed, on which O’Connell had died in May 1847, in Genoa in Italy, is part of the display, as is an imposing ceremonial carriage that conveyed O’Connell from prison to his Dublin home on Merrion Square.

Again, the program for the second day offered a rich variety of papers, including a talk by Dr. Colum Kenny on Father John O’Sullivan, parish priest of Kenmare during the Great Hunger, who traveled to London on behalf of his parishioners and was hosted by both John O’Connell and Charles Trevelyan.

Other topics included two papers on “Caricatures and Cartoons,” one of which was given by Rickard O’Connell, a descendant of Daniel, who is a collector of visual prints relating to his ancestor. Daniel O’Connell’s rich legacies were also explored through papers on the opening of the Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin, an exploration of the eighteenth-century world in which the O’Connell family flourished, and on O’Connell as Lord Mayor of Dublin in the 1840s.

My own paper focused on O’Connell as a champion of human rights, particularly in regard to his role in ending slavery. I examined his contribution to the first International Anti-Slavery Convention. The Convention was attended by over 600 delegates from all over the world, but O’Connell was the undoubted star, being cheered whenever he appeared.

The gathering was groundbreaking and fascinating for multiple reasons. The exclusion of women from the conference and denial of their status as delegates, for example, changed the course of American history. Two of the women who were excluded – Lucretia Mott and Lucy Cady Stanton – “walked home arm in arm, commenting on the incidents of the day, [and] we resolved to hold a convention as soon as we returned home, and form a society to advocate the rights of women.”

The result was the Seneca Falls Convention held in 1848. O’Connell, in a show of support for the excluded women, sat with them every day in the “ladies’ gallery.” Mott regarded his company as “excellent and amusing,” while Stanton described him as “tall, well-developed, a magnificent looking man, and probably the most effective speaker Ireland ever produced.”

Overall, it was impossible to leave the School without feeling that O’Connell was an incredible international statesman, and that County Kerry truly is “The Kingdom,” the local saying being, “There are only two kingdoms, the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Kerry.” The small organizing committee, which includes Maurice Bric, Mary O’Connor of Derrynane and Ruth Barrington, are to be congratulated for making the O’Connell School so vibrant, relevant and enjoyable. It was an amazing experience.

For further information visit:

www.danieloconnellsummerschool.com

Professor Christine Kinealy is Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University and her publications include Daniel O’Connell and the Anti-slavery Movement (2011) and Black Abolitionists in Ireland (2020).

Note: The concept of a ‘School’ is familiar to many Irish people. They are usually named in honor of a famous person (there are also Yeats’, Parnell, McGill and Merriman Schools) and they are part of a well-established educational tradition in Ireland. Schools are far broader in their reach than academic conferences, as they involve a wide range of speakers and are very much grounded in the community where the person lived.

Professors Christine Kinealy of Quinnipiac University

and David Dickinson of Trinity College, Dublin.

Leave a Reply