by Niall O’Dowd from Irish America’s Premiere Issue in 1985

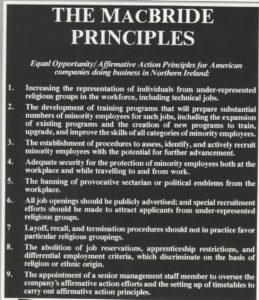

Editor’s Introduction: The MacBride Principles aimed to secure the elimination of religious or anti-Catholic discrimination in the hiring process or employment practices of U.S. corporations with subsidiaries in Northern Ireland.

The Principles would forbid the subsidiary companies from exporting their respective products into the States unless they subscribed to the MacBride Principles. It also lobbied that the pension and retirement funds that were currently invested in the Northern Irish subsidiaries be funded by companies that endorse the Principles prospectively.

It was a highly contentious policy suggestion that sparked a heated debate in U.S. Congress and triggered unrelenting acts of suppression by the U.K. government.

Irish America’s founding publisher wrote this piece on the MacBride Principles in the 1985 Premiere issue and eloquently details the early struggles of its supporters.

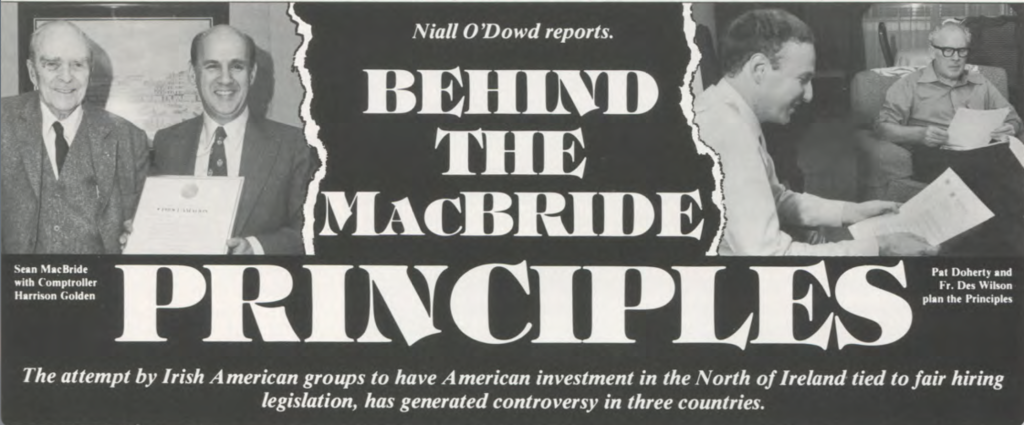

The MacBride Principles, named after Nobel Peace Prize winner Sean MacBride, have recently become major news in the U.S., Britain, and Ireland. The Principles are the latest attempt by the Irish American lobby to equate Northern Ireland with South Africa in the matter of employment discrimination.

Based on the Sullivan codes that seek to determine how U.S. corporations hire in South Africa, the MacBride Principles look to ensure similar equitable hiring practices by  U.S. companies with subsidiaries in the North of Ireland.

U.S. companies with subsidiaries in the North of Ireland.

To date, The New York Times, the New York Daily News, the London Sunday Times and many other leading newspapers have editorialized on the Principles, while searching questions have been asked in both the British and Irish Parliaments. Both Irish Prime Minister Garret FitzGerald and his British counterpart Margaret Thatcher have discussed the Principles with top-level U.S. officials during separate visits here and the Principles have now become part of the U.S. Anglo/ Irish agenda.

In effect, the MacBride Principles are the most important initiative to spring from Irish America in recent times, avoiding the fate of most such initiatives which usually get snagged in the ethnic ghetto amidst fierce infighting as to who should take credit for what.

The story of the evolution of the MacBride Principles, from their humble beginnings in an obscure Brooklyn newspaper to their becoming the subject of international discussion, is a fascinating hodge-podge of New York politics, Irish American power plays and constant maneuvering by those concerned to make the Principles a high-profile issue.

At the center of the Principles issue is the unlikely figure of Harrison Jay Goldin, the forty-nine-year-old comptroller of the City of New York, the third-highest elected official in the City, and the man who oversees billions of dollars in City pension funds investments.

Goldin, who is Jewish, is an extremely competent and ambitious politician who, no doubt, would like to sit in City Hall someday. He knows that now is the time to build the ethnic alliances that are part and parcel of gaining that job.

As a prominent city official with an impeccable civil rights record (he once worked with Robert Kennedy in the Justice Department), Goldin has already gained widespread kudos from blacks and other groups for his part in ensuring that New York City funds were divested from companies doing business in South Africa.

With that success behind him, and no opposition of note against him for re-election, Goldin began to look around for another issue that could similarly allow him to tap into another of the ethnic power blocks that make up New York City.

It was Jim Cassidy, one of his staff men whose job it is to recruit new ideas, who clipped an article from the Brooklyn Spectator, written by Dennis McMahon in September of 1983. That article, for the first time in print, linked U.S. investment in South Africa and the North of Ireland and discussed the possibility of Sullivan-like principles working for Ireland.

The Irish issue was an obvious one for Goldin to consider Quite apart from his civil rights concerns, it afforded an entree into a major ethnic block. Though the Irish may never again elect one of their own mayor of New York City, they now represent a crucial swing vote, much courted by both Italian and Jewish candidates in mayoral and congressional races. The high profile of a slew of Italian and Jewish candidates on the Irish question, readily attests to that.

In addition, though some Irish Americans express cynicism on the matter there is little doubt among other ethnic groups that the Irish still have considerable clout in New York elections. The 1985 Irish Northern Aid dinner, for instance, stands as the largest political dinner held in New York this year.

“Putting 1,300 people into a room makes everyone sit up and pay attention,” says one political aide, “no politician is going to ignore those numbers when most groups have problems mustering 300 at a function. The Irish may truly not know their own political power.”

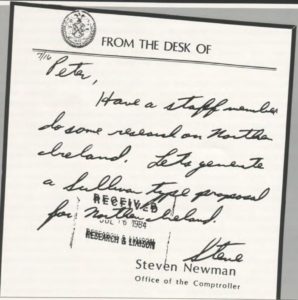

Following Cassidy’s original clipping of the McMahon piece, the idea found its way in memo form to Steve Newman, assistant comptroller Coincidentally, Newman had recently become quite interested in the Irish question due in part to his having worked on the Gary Hart campaign where the Irish issue was used successfully. In fact, he had just finished reading Trinity, by Leon Uris which is set in Ulster when the memo crossed his desk. He was quick to see its potential.

With Newman pushing it, the idea was an easy sell to Goldin, anxious as always to adopt high-profile issues for an office which receives relatively little media attention. He conditionally gave the go-ahead.

The next step for Goldin’s office was to appoint an “Irishman” to build a case for the Principles. As it happened, they had an ideal person in their ranks, 30-year-old Pat Doherty, the red-haired son of Derry and Fermanagh immigrants who, while relatively uninvolved in the Irish question to that point, did have a solid grounding on the issue.

Doherty, a newcomer to the comptroller’s office, has a master’s degree in international relations from Columbia and a law degree from Hofstra. He had previously worked with Newman in the Hart campaign, and Newman, liking what he saw, had hired him for the comptroller’s office. The MacBride Principles was his first major assignment.

Goldin had given the go-ahead for the campaign with one proviso. He himself. Or his office, could not be publicly linked at first, in the event of a backlash. There were powerful business circles in New York upset at his disinvestment program for South Africa, and his interest in the Irish question.

As a consequence, Doherty had to come up with an Irish American organization that could publicly carry the plan and also have enough resources and clout to give it legitimacy His choice was the Irish National Caucus, a Washington-based lobbying group headed by Fr Sean McManus. Since 1974, the Caucus had been a consistent thorn in the side of the British Government in the United States, and it had a solid track record of legislative accomplishment on Irish issues.

For Fr McManus, who at the time was working to prevent major U.S. defense contracts from going to companies in Ireland who allegedly discriminated against Catholics, the Goldin initiative was a welcome one. “You have made a magnificent and inspiring contribution to the cause of freedom and human rights in Ireland.” MacManus wrote to Goldin upon hearing of his efforts.

While McManus agreed to push the as yet un-named Principles, Doherty began the long, often tedious task of contacting the various organizations with a stake in the Irish question and gathering all relevant information on employment discrimination.

Surprisingly, he found the British to be more than cooperative. He was inundated with information from the British Information Service, most of it seeking to show that the Fair Employment Agency in the North was phasing out all discrimination which even they admitted, had existed.

Doherty was finding sharply differing views on the other side. Fr Brian Brady, long a chronicler of employment abuses against Catholics in the North, sent him a detailed survey, apparently proving that things, far from getting better were getting much worse.

Meanwhile, back at the comptroller’s office, researchers had discovered that New York City Pension Funds held $247 million dollars. worth of investments in 13 of the 24 U.S. companies with subsidiaries in Ireland. Of that total. $80 million was invested in General Motors, $40 million in Ford, and $21 million in United Technologies, making those three companies the largest recipients of New York Pension Funds.

Some of the discrimination charges against U.S. company subsidiaries were quite serious. At the General Motors Corporation subsidiary in Dundonald, for instance, there was, according to Nationalist sources, “a well-documented history of intimidation and violence, including murder against the Catholic workforce.” In 1981, after management ordered the removal of anti-Catholic slogans from the workplace, many workers went on strike. The management then allowed the symbols to stay.

At Gallaghers, the American Brands subsidiary in Ireland, things were even worse. The firm had become notorious for its discriminatory hiring practices and had even drawn the fire of the Fair Employment Agency (F.E.A.), a group generally regarded by Nationalists as a body without teeth.

Other subsidiaries cited by the F.E.A. as being under-represented by Catholics in the workforce included the Hughes Tool Com- pan plants in Monkstown and Belfast.

One should bear in mind, of course, that Catholic unemployment figures in the state as a whole are roughly two and a half times higher than the Protestant ones, that Catholics tend to occupy the lower-paying jobs and have done so for generations, and that American companies are certainly no better or worse on discrimination than any other com panes doing business in the North.

Doherty, in conjunction with MacManus, was able to establish almost irrefutable evidence that proved that American companies, which employ 11 percent of the workforce in Northern Ireland, were part of an ongoing cycle of discrimination. Doherty then prepared a set of nine principles to ensure that American companies with New York Pension Funds invested would, at least, sign fair hiring principles and, at best, cease to discriminate.

The Principles are modeled closely on the Sullivan Principles, which have worked so effectively in South Africa. To give them greater gravitas, Doherty, at the suggestion of McManus, persuaded Nobel Peace Prize winner and Amnesty International founder Sean MacBride, a revered figure to millions in Ireland and in the U.S., to lend his name to them. Thus, the MacBride Principles were born

In addition to MacBride, two other figures of significance signed them. Dr John Robb, a member of the Irish Republic Senate (one of the first ever from the North), and Inez McCormack. A former member of the Fair Employment Agency.

The publication of the Principles caused much comment in Britain and Ireland. The London Sunday Times wrote that “the campaign being run by the Irish National Caucus …is particularly well-timed. For even if the law is never passed it provides an opportunity to link, however tenuously, the issues of South Africa and Northern Ireland… The MacBride Principles also call for the same kind of affirmative action programs for Catholics which American companies already use in the employment of women and blacks in the U.S.”

Goldin’s role in the formation of the Principles was still not widely known, though the Irish National Caucus and the ethnic Irish media had reported it. In fact, there was still an unresolved tension among his staff as to the comptroller becoming too closely identified. Several staff members felt that principles aimed against the Soviet Union for their treatment of Jews, or Turkey for its treatment of Armenians would be just as successful.

Then a development occurred that forced Goldin’s hand. New York City Councilman Sal Albaneese was intrigued by the Principles for much the same reason as Goldin had been. He decided to sponsor a measure in City Hall designed to amend the New York charter in relation to limiting city pension fund investments in certain companies that did business in the North of Ireland. The proposed new law, which essentially called for disinvestment, was more far-reaching than Goldin’s, which called only for the signing of fair-hiring agreements by the companies as an initial step.

With Albaneese’s proposed bill announced to a packed City Hall press conference, Goldin was in danger of becoming the forgotten man of the whole initiative. When a spokesman for his office erroneously replied to a newspaper inquiry that Goldin was against the entire pension funds scheme, it was duly reported in the New York media that Goldin opposed all action against U.S. companies in Ireland. When the anti-Goldin mail began to arrive from Irish constituents, the irony of it all was not lost on the comptroller’s office.

Moving quickly now, Goldin re-established his office as the primary mover and shaker behind the initiative. Well-publicized meetings with the management of General Motors and written statements to twelve other companies cited for unfair hiring practices was followed by a calculated effort to establish a higher profile in the Irish community. This included appearances at Irish Solidarity Day and the Irish Northern Aid Dinner, The largest Irish function of the year and one shunned by many politicians uneasy with the alleged I.R.A. fundraising link to the organization.

In June of this year, Goldin played his trump card and made a personal visit to Northern Ireland, accompanied by staff member Doherty. The publicity during their visit, which was paid for by the Irish National Caucus and included a meeting with top-level British politicians, was continuous. Back home in the U.S., The New York Times and The Daily News ran lead editorials on Goldin’s efforts. Much of the editorial comment was negative, reflecting the view that the Principles could hurt as much as help the situation in the North.

Goldin, however was very happy with both the publicity and the response. His name was in every major New York newspaper and at the comptroller’s office, over 150 letters arrived, only four of them negative. “Goldin was tapping what shrewd New York pols knew was already out there,” says an aide to the comptroller, “a wellspring of support for any politician who spoke out on the Irish issue.”

Currently, Goldin’s office is pursuing those U.S. companies in Northern Ireland that are directly affected by the MacBride Principles. They have encountered stiff and well-organized opposition from the British, and to date none of the companies concerned has indicated a willingness to sign the Principles.

Significantly, however there has been a number of inquiries from other comptrollers across the U.S., particularly in the large cities, about the MacBride Principles and how they could apply to pension funds in cities such as Chicago, San Francisco and Philadelphia.

Nonetheless, one must differentiate between potential and actual results to date. As currently constituted, the MacBride Principles could be said to be a failure so far None of the U.S. companies doing business in the North of Ireland have signed them. One, General Motors, has flat-out refused to do so, while the others are still considering them. The British have scored points by telling U.S. companies that the Principles are actually illegal under their law, and the Irish government has been, at best, ambivalent in its support.

Only in an American context do the Principles seem to have worked. All the major Irish American organizations, and especially Comptroller Goldin, have an issue that has given them much-needed exposure and coverage. In addition, the specter of the powerful Irish American lobby, so feared by the British government, has begun to loom large as the major American media finally pays attention to an Irish American-based initiative.

In the past it was easier for that same media to concentrate on catchcries’ and anti-I.R.A slogans than to undertake any serious analytical approach to the issue of Northern Ireland. The MacBride Principles could signal a maturing of the coverage of the U.S. media and prove to be a boon to the Irish American coalition, a group no longer chronically dependent on reacting to events in Ireland for their raison d’etre.

Editor’s Note:

In 1999, President Bill Clinton signed them into law as part of an Appropriations Act for the Fiscal Year. In the 20+ years that the MacBride Principles have been established, the region has reached stability and peace – the Good Friday Agreement was signed into law, and a Northern Ireland Protocol for trade post-Brexit was announced.

Yet the power of boycotts and non-violent principles for anti-discrimination and inclusion efforts still holds strong. After all, the boycott was created by an Irish man, Charles Stewart Parnell, who protested high rents and land evictions. There is proof of that power, and you can see that in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Anti-Apartheid Movement in South Africa, and the BDS movement led by Palestinian activists.

Leave a Reply