Irish nurses, in fiction and in real life, shaped nursing and healthcare in the U.S.

There is a moment late in J. Courtney Sullivan’s excellent 2017 novel Saints for all Occasions when “hundreds of people showed up” to a Boston Irish American wake. Among the mourners are a trio of sisters, “Peggy, Patrica and Jane, all of them nurses…two of them wore scrubs beneath their winter coats, only on an hour’s break.”

A character taking in the scene looks back on her life, and thinks about her parents, and how they “had presumed once that she too would be a nurse someday.”

This scene – and, in some ways, Sullivan’s entire multi-generational book – illustrate the many subtle and profound ways Irish Americans shaped nursing and health care, and vice-versa.

From Lower Baggot Street in Dublin, to the first hospitals ever opened in rapidly-expanding U.S. cities, Irish immigrants played a central role delivering health care and other social services to needy newcomers.

But it’s been a long, strange, and complicated trip, one inextricably tied to other important issues – religion and discrimination, poverty and gender norms.

The end result, though, is that from the blood-soaked battlefields of the U.S. Civil War, to the front lines of COVID, Irish health care providers have been there in great, dedicated numbers.

From Abbeyleix to Pittsburgh

Laois native Frances Warde was an early nursing pioneer on both sides of the Atlantic.

Born in Abbeyleix in 1810, Warde lost her parents at a young age, and after pursuing a religious vocation, began working with Sister Mary Catherine MacAuley, the famed founder of the Sisters of Mercy religious order.

The first House of Mercy opened on Dublin’s Lower Baggot Street in 1827, providing a range of services to needy women. Even before the Great Hunger of the 1840s, it was clear that the Irish in America were in desperate need of the same services – on an even bigger scale.

By the late 1840s, Mother Frances Warde and six other Sisters of Mercy had opened, and were operating, the first hospital in Pittsburgh – which is still in operation today, as the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

When it first opened, “Everyone was welcomed regardless of race, nationality, age, gender, or religion,” the UPMC website currently notes, adding that “Mercy established the region’s first teaching hospital with resident physicians in training in 1848.”

Similar initiatives were undertaken in other cities where large numbers of Irish Catholic immigrants congregated. Their desperate conditions meant they were in need not just of medical care, but food, shelter, education and more.

Nuns not only provided these essentials, they became more broadly experienced in both the administration and practice of an array of fields, not just one specialized skill.

More and more Irish women – and it was mostly women, since society deemed them genetically more “nurturing” – were working in hospitals. Women like the remarkable Tyrone native Angela Hughes.

A Brother’s Shadow

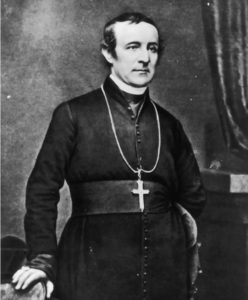

Angela’s older brother is the more famous member of the Hughes clan.

“Dagger John,” as he came to be known, was arguably the most important Irish Catholic immigrant of the 19th Century, presiding over the construction of churches, schools, hospitals and more, as bishop of Philadelphia, then New York.

Along the way, Hughes confronted anti-Irish nativists, many of whom adhered to an older version of what is today called the “great replacement theory.” These bigots believed Irish Catholics were destroying America – what had once been a great Protestant nation.

“Dagger John” would not have been able to prove them wrong – or build much of anything – without the ambitious and visionary likes of his younger sibling, who became Sister Mary Angela, after joining a Sisters of Charity order in Emmitsburg, Maryland.

She initially worked with orphaned children, before moving on to what is generally considered the first Catholic hospital in the U.S., funded largely by Fermanagh native and successful merchant John Mullanphy.

St. Louis’ Mullanphy Hospital was also one of the first such facilities run mainly by women. In the decades that followed, Sister Mary Angela Hughes was at the forefront of providing social and spiritual services to millions of Irish immigrants who fled the famine. Along the way, she had her own feuds – with nativists, as well as her own brother, and others in the entirely-male American Catholic hierarchy. They fought over who could and should deliver social services to the needy – and how to pay for it all.

This would not be the last time nuns and other women did battle with male church officials.

Either way, by 1849, Sister Mary Angela was confronting a cholera epidemic in New York, and founding St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan. She also oversaw the opening of schools and convents, until her death in 1866 – two years after her brother died.

Obstacles and Opportunities

Hughes illustrates, if you will, the mixed blessings of the New World – Irish Catholic women were undeniably limited to certain fields. However, within these strictures, they were given opportunities to develop and showcase valuable skills – even if they rarely received proper credit for their work.

By the 1850s, there were Irish Sisters of Mercy working in New York City, Chicago, Little Rock, and San Francisco. This reinforced – for better and worse – the centrality of Catholicism in Irish American life, while allowing the Irish to survive, and later thrive, in America. Generations were raised in parishes and enclaves with cradle-to-grave Irish Catholic services and experiences.

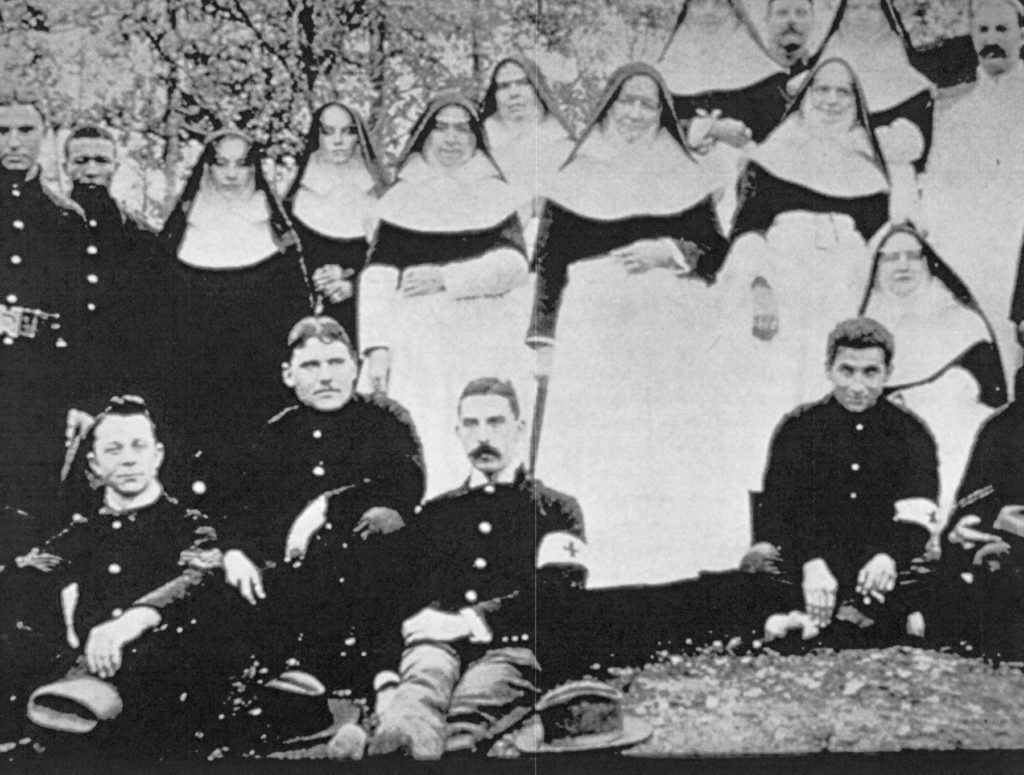

When blood was shed during the U.S. Civil War, an estimated 600 nuns from up to a dozen religious communities tended to the soldiers – even if different hostilities persisted.

Famed medical pioneer and Union Army Superintendent of Nurses Dorothea Dix “harbored significant prejudice against the Catholic sisters, chastised their attire, and alluded that they were unsatisfactory for the patients,” according to Samford University historian Keely Smith. Dix and other upper-class Protestant medical administrators felt “threatened by the high esteem with which the surgeons held the Sisters of Charity,” and reflected “an underlying current of anti-Catholic sentiment prominent at the time that many of the Catholic sister nurses had to overcome,” according to Prof. Smith.

One nursing textbook also notes that Florence Nightingale’s parents – as “steadfast members of the Church of England” – were shocked the future nursing trailblazer once pondered seeking “admission to a convent of Irish Catholic nursing sisters.”

In Tenement Slums

In the decades after the Civil War, immigrant nurses in big cities often competed with missionaries not only offering medical care, food and shelter, but also opportunities to leave so-called “slums” behind – to go to live with Protestant families on rural farms. Critics howled that these “orphan trains” were anti-Catholic efforts to break up Irish families and convert urban Catholics.

Still, slowly, women – even those who did not become nuns – cleared more paths to work outside the home. Colgate University historian Graham Hodges has described the shared experiences of African American and Irish immigrant New Yorkers during and after the U.S. Civil War, amidst crippling poverty and discrimination.

“Delayed martial patterns, access to education, and cultural influences trickling down (from more affluent households) enabled black and Irish domestics to move up in society,” writes Hodges. “As modern forms of education and medicine blossomed, single and late-marrying women found opportunity and class mobility in school teaching and nursing.”

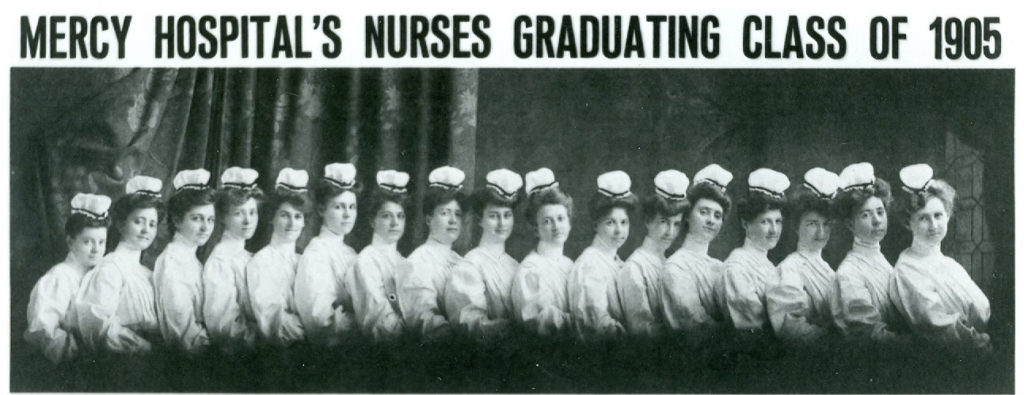

By the mid-1870s, there were schools dedicated to nursing in New York, New Haven and Boston – three cities with high Irish immigrant populations. Nursing was “the only profession other than teaching open to Irish women as late as the 1880s,” James R. Barrett writes in The Irish Way: Becoming American in the Multi-Ethnic City. And so, “city hospitals and nursing programs were loaded with Irish women.”

This often meant tending to fellow Irish immigrants – under terrible circumstances. Poor Irish immigrants still “practiced a religion which Protestant physicians found particularly depraved and offensive,” writes Stacy Horn in Damnation Island: Poor, Sick, Mad and Criminal in 19th Century New York. “Some asylums even had separate Irish wards.”

Much of this medical and cultural anxiety came together and transformed one unlucky Irish immigrant domestic worker, Mary Mallon, into “Typhoid Mary” in the first decade of the 20th Century.

Beyond Marriage & Spinsterhood

The world war – which America entered in 1917 – brought more opportunities for Irish nurses to prove their patriotism.

“Nineteen Roman Catholic nurses from the Sisters of Charity of Saint Vincent DePaul and other orders deployed to Vicena, Italya,” according to It’s My Country Too: Women’s Military Stories from the American Revolution to Afghanistan. By one estimate, the American Red Cross recruited 22,000 nurses to serve in the U.S. Army between 1917 and 1919, and nearly half served on the notoriously dangerous Western Front.

Still, even when celebrated Irish American novelist Alice McDermott thought about her Brooklyn youth, nursing and religion were still intimately combined.

“The route that was open to women when they were coming of age was pretty limited: marriage or spinsterhood,” McDermott once said.

“If you got married, you were just going to have a pack of kids …. If you didn’t marry, you could be a school teacher. You could be a nurse, but even in those days there was some kind of suspicion about what kind of woman you were if you wanted to be a nurse and you were a single woman.”

Challenging this is one reason McDermott’s 2017 novel about nuns, The Ninth Hour, is so extraordinary.

“The culture’s portrayal of religious women is really flat,” McDermott added. “And the more I read about (nursing) orders…the way these women went into battlefields, they went into the inner cities, into tenements, into the homes of the sick and the dying, into epidemics.”

The Ninth Hour opens with a tragedy. Then, one “Little Nursing Sister of the Sick Poor” springs into action, to help a desperate, pregnant young woman.

“What we must do,” the nun declares, “is to put one foot in front of the other.”

Aside from McDermott’s trademark poetry and quiet drama, The Ninth Hour also features a fascinating blend of religious and lay women, one that almost seems to span the generations of the Irish American experience.

Fittingly, there are squabbles that call Sister Mary Angela Hughes to mind.

“It would be a different church,” one Ninth Hour nun declares, “if I were running it.”

From TV to the Doctor’s Office

In more recent decades, popular culture has given us Irish nurses from Margaret “Hot Lips” Houlihan in MASH, to Sinead O’Rourke in the recent NBC drama Nurses.

Early versions of the groundbreaking cable show Nurse Jackie featured Edie Falco as a troubled title character “Jackie O’Flaherty,” though that name was later changed.

Still, nursing began to reflect different tensions with the Irish American community.

In Saints for All Occasions, a newcomer from Ireland to a boarding house run by Mrs. Quinlan creates tension by airing what some might call overly-grand ambitions.

Mrs. Quinlan – a woman of some accomplishment herself – chooses this moment to remind everyone present: “I was a nurse myself for years.”

The celebrated Queens-born Catholic writer, Mary Gordon, once remembered being frustrated by her students – aspiring “police officers, nurses, dental hygienists” – who did not take literature as seriously as she did.

The Telegraph newspaper once wrote of another Irish American “from New York’s tough Queens area, (whose) Irish immigrant father left school at 14 to start work.” Bernadine Healy was “smart and ambitious” and in the past might have become a nurse – like Mrs. Quinlan.

Healy, though, “won full scholarships to Vassar and Harvard,” became a doctor, and went on to an accomplished career in the medical profession.

Ultimately, across the decades, nursing and other health care work gave Irish women some of the same things political organizations offered to their male immigrant counterparts: camaraderie, connections, commiseration, and access to power, if not always credit and attention.

When a crisis arrives in Saints for All Occasions, one character – a nurse – addresses a worried group of family members.

“It’s alright…calm down. I’ve talked to a nurse at the hospital who knows someone.”

All in the Family: The Millea Sisters

by Holly Millea

To quote history’s most prolific writer/philosopher Anonymous: “Save one life, you’re a hero. Save a hundred lives, you’re a nurse.” By that estimate, in just one Emmetsburg, Iowa family, four nurses saved hundreds of lives.

The first set of healing hands belonged to Mary Kay Millea, the eldest of 13 children born to Mary Mahoney and William “Bill” Millea, whose first six babies were born at home. At an early age, Mary Kay was nicknamed “Mother Superior” for the firm kindness she deployed when keeping her younger siblings in line. “Her sisters called her that behind her back,” recalls her brother Mike, a retired policeman, educator and counselor. He laughs. “They were always trying to make her cry. But the only time I ever saw her cry was when someone died. She was the salt of the earth, so kindhearted.”

After graduating from high school, Mary Kay left Emmetsburg for Chicago, where she channeled her caretaking skills and gentle nature into a nursing degree, graduating from Saint Xavier college in 1944. “She was so deeply satisfied with her life and career, she never had children of her own,” says her brother Roger, a retired urologist. “She didn’t even marry until she was over forty.”

By then, her three youngest siblings had each undergone a nursing-pinning ceremony reciting “The Nightingale Pledge,” which reads in part: “…I shall be loyal to my work and devoted towards the welfare of those committed to my care.”

In 1961, Margaret graduated president of her class from St. John’s School of Nursing in Huron, South Dakota, in 1960. Joan and Geri graduated from Creighton Memorial St. Joseph’s Hospital School of Nursing in Omaha, in 1963, and 1965 respectively. “My father always called us ‘the mice’ because we slept in the same bed and did everything together,” Geri says. Everything including their double wedding ceremony at St. Cecilia’s Cathedral on June 6, 1964, Joan marrying John Belda, and Geri saying “I do” too, to Robert Zilm. (Each of the mice went on to have six children.)

Joan first worked as an instructor and pediatric nurse at St. Joseph’s, ultimately moving to Sun Prairie, Wisconsin where she opened a home daycare center which thrived for three decades.

Moving to California, Geri spent over two decades as an R.N. “When you begin it’s kind of scary – you’re not used to doing some of the things you’re learned to do. It made you squeamish sometimes,” she admits. “Joanie was a tougher bird than I was.”

Margaret meanwhile, was living on the opposite coast in Atlantic City, with her husband Don Weatherby and their four children. She reveled in the practice and care of patients for 43 years, until she passed away at 70 of cancer.

Two years later, in 2010, her big sister Mary Kay, 87, died of Alzheimer’s. Her beloved husband Charles Schmidt followed three years later, his obituary noting he was “best friend and father to Cutie Pie” their adopted chihuahua. But before he died, Charlie paid tribute to his late wife with a donation to her alma mater, funding a nursing laboratory on St. Xavier’s campus; and establishing the Mary Kay Millea ’44 and Charles E. Schmidt Scholarship, awarded annually to a student attending St. Xavier’s School of Nursing and Health Sciences. It is an invaluable inheritance left to strangers, who in turn, will save hundreds of lives.

Leave a Reply