Her likeness appears on a banknote and in portraits by famous artists.

Who was Lady Lavery

Women rarely have their faces on currency. Except, of course, for the recently departed Queen Elizabeth II who was on the currency of Great Britain and her colonies for over 70 years and, until recently, showed no sign of retiring or expiring.

In 1928, Ireland, too, cast a woman on the banknotes of a new, free Ireland, Lady Hazel Martyn Lavery, a great beauty and a woman of some notoriety. Lady Lavery was a society queen in London, and hostess of dinner parties attended by British aristocracy, diplomats, and writers, including G.B. Shaw and W.B. Yeats. She was a 6th generation Irish American from a wealthy family, a gifted artist married to (and muse to) another artist, John Lavery. But, in time, she found her true voice, the cause of Irish nationalism and freedom from Britain.

In 1903, after secondary school and her debut, she traveled to Brittany to study sketching. At one point she visited a fortune teller who gave her an unpleasant, if prescient reading: “Your wit is inclined to many conversations, and you will do great mischief, dangerous to others, therefore you will have bad luck.”

Hazel’s talent was impressive, her portfolio earned her the reputation of a promising new talent. She also met John Lavery, a famous and prolific artist, and the royal family among his many subjects. Orphaned at three, Lavery was Catholic from Presbyterian Belfast, a difficult world for a child without a family. John and Hazel, a most unlikely duo, fell in love. Lavery was 30 years older, a Catholic, a bohemian, and a widower. It all horrified Hazel’s mother who quickly got to work marrying Hazel off to a young doctor in the U.S. But after four months of marriage, the young doctor dropped dead leaving Hazel two months pregnant. It didn’t take long for Hazel to renew her relationship with Lavery planning to rejoin him, with her baby, Alice, in Europe. But, again Hazel’s mother thwarted their plans. It was a six-year battle that only ended when Mrs. Martyn died and the couple had the questionable taste to marry 22 days later.

The Laverys, in 1909, moved to fashionable Cromwell Place where she became the most dazzling society hostess in London; she entertained all the time while her husband painted all the time. Hazel had many male admirers, single and married, who lavished her with gifts, flowers, and poems forcing some wives to found a Husband Protection Society. There was much gossip about who, if any, of her devotees was her lover. (Your wit is inclined to many conversations, and you will do great mischief …)

She submerged her own artistic ambition becoming, Lavery’s muse and in effect, his agent. Always charming she would take guests into his studio to show them his latest work invariably winning commissions. One subject of Lavery’s was Winston Churchill; Hazel him taught to paint and, in time, the old Bulldog showed real talent.

The Laverys followed the 1916 Rising with interest, she had Irish blood and he was from Ulster, Northern Ireland. Then Lavery received a controversial commission – paint the high treason trial of the knight-turned-rebel, Sir Roger Casement. Since Casement was, like Lavery, an Ulster native, his trial for his smuggling arms for the Rising, was held in London. Casement said he was not a traitor since he was Irish and not a British subject.

As her husband painted the scene, Hazel daily sat in the gallery, fascinated by Casement. He was a knight of the realm, the greatest humanitarian of his day, the man who exposed the murders, tortures, and mutilation King Leopold of Belgium brought to the natives of the Congo. Exploitation and greed, Casement realized, were business as usual for empires, including the world’s largest, the British Empire. His dormant Irish nationalism awoke; he shed his Anglo skin and found the Irishman underneath.

After Casement was hung, and his naked body thrown into an empty grave, Hazel, too, was profoundly changed – she shed her American skin and found her Irish soul. By 1920, she had completely dedicated herself to the cause of Irish nationalism, believing she could help bring peace between England and Ireland. She converted to Catholicism.

In 1922, after 800 years of rule, British troops marched out of Ireland, and she was now ready to negotiate a treaty with Great Britain. President Eamon De Valera made an attempt but quickly surmised there wasn’t a solution that would satisfy both sides. Exiting the no-win situation De Valera sent what could only be called a scapegoat, the young Michael Collins. Collins was the Director of Intelligence for the IRA whose guerilla warfare and Intelligence network brought about the cease-fire.

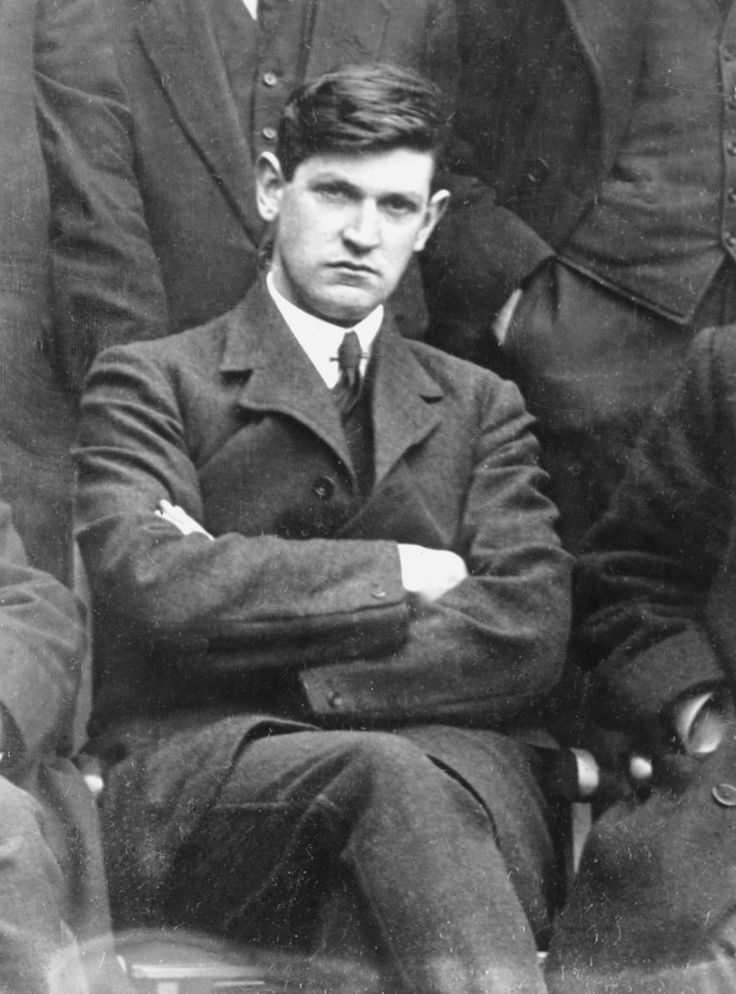

Michael Collins was one of history’s most romantic characters. Handsome with a shock of black hair, he was unusually tall for an Irishman, hence his nickname “The Big Fella.” He was brilliant, fearless, and charming – men loved him, women loved him including the fabulous Lady Lavery and who could blame her? What followed next was one of the great questions in Irish history, “Did they or Didn’t they?” Even today the speculation continues.

But those close to Collins knew how devoted he was to his fiancée, Longford country girl, Kitty Kiernan. The consensus today is Collins/Lavery had a loving friendship, were soulmates rather than bedmates. He appreciated Hazel’s deep intelligence, always overlooked because of her beauty, and often followed her opinion during negotiations. A snarkier point of view was expressed by Terence de Vere who asserted the romance was one-sided on Hazel’s part. “Lady Lavery, it must be confessed, gave the rumors wings.” London papers hinted at an affair but at home, in Longford, the good-natured Kitty teased her fiancé about his “Lady.”

Hazel was a vortex of Irish patriotism. She was fervent, almost possessed, giving her all for Ireland. During treaty negotiations, Hazel hosted dinners and unofficial meetings for the framers of the Irish Treaty. The Lavery home was a safe, warm, and relaxing place, more ideal for negotiation than the official government office. She was the intermediary, a de facto diplomat between Collins’ team and the Brits, Lloyd George, and Winston Churchill.

On December 6, 1921, the Anglo-Irish treaty was signed: the Irish Free State was born. It should have been a glorious moment but it wasn’t. The Treaty, though imperfect, was the best the Free State could hope for—Collins (and De Valera) knew a signed treaty would lead to Civil War. A minute after he put his name down, Collins turned to Churchill, “I’ve just signed my own death warrant.”

The following August crossing Ireland, hoping to reconcile pro-and anti-treaty forces and hoping too, to stop any bloodshed, Collins was shot and killed in his native county of Cork. He was only 32. Many historians believe Collins’ death brought about the ascendancy of De Valera whose fervid Catholicism impacted Irish culture for almost a century. The country soon devolved into a theocracy.

After Collins’ assassination Hazel did take on the aspect of a widow and many accused her of being theatrical. Nonetheless, Kitty Kiernan and Lady Lavery embraced at Collins’s funeral and Sir John Lavery presented Kitty with the portrait he painted of Collins. Three years later, Kitty married a soldier, Felix Cronin, and the laughing, vivacious girl became a slog in a loveless marriage. She and Felix had two sons, the first named Michael Collins Cronin and the Big Fella’s portrait loomed large in their home.

Hazel, however, recovered. By 1923 she had developed a close friendship with Kevin O’Higgins, Ireland’s Minister of the Interior (and an intimate of Collins); by 1924, the relationship had transcended friendship. O’Higgins wrote, “I had to tell you just once, that you are not ‘one of my friends’ but altogether the sweetest, most wonderful influence in my life.” His wife and children vaporized, and O’Higgins was in love. As she had with Collins she introduced him to the right people and helped him play an important part in the Imperial Conference. But Lavery looked up from his canvas and at long last realized he might be a cuckold. He whisked Hazel off to America, a place she had come to loathe. O’Higgins was miserable without her.

By 1927, Hazel had rejoined O’Higgins in London. On a Sunday in July, O’Higgins was on his way to mass when he was shot by anti-Treaty IRA men. His dying words were, “I forgive those who have done this, I die for my country.” Once again, Collins redux, Hazel was a shadow widow, writing she was “frozen in misery and utterly alone” after the assassination; she requested that her brooch be buried with O’Higgins. (“…dangerous to others, therefore you will have bad luck.”)

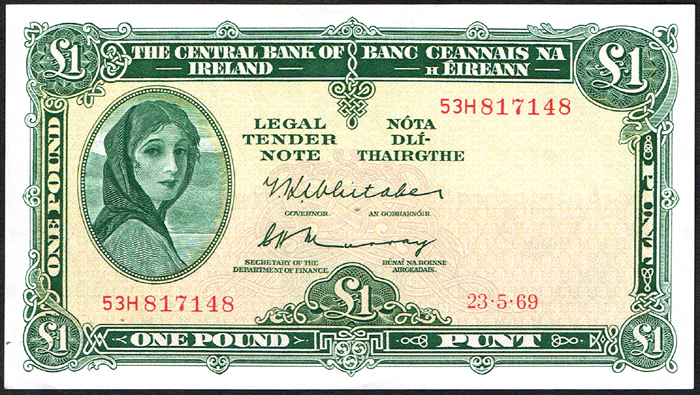

Time goes on: the new country needed new currency. The Currency Commission wanted to have Kathleen Ni Houlihan, the mystical representation of Ireland, on the pound note. Kathleen Ni Houlihan, a character in play by Yeats and Lady Gregory was an old woman lamenting British occupation, urging young men to fight for Ireland. She succeeded and at the end of the play she was transformed into a beautiful young woman.

The Currency Commission appointed Lord John Lavery as the artist and he, in turn, chose his favorite subject, his wife, Kathleen Ni Houlihan. There were charges of nepotism at first but they died down after the notes went into circulation in 1928: they were arguably the most beautiful and iconic currency in the world.

Hazel died in 1936, at just 54. John Lavery, the man Mother Martyn deemed “too old” for Hazel lived to be 84. But the Lavery banknote outlived them all. Though her name and invaluable contribution to Irish Independence had been long forgotten, she continued to exist in the wallets of Irish citizens for the next 50 years, until 1977.

I visited Cromwell Place today and came upon your delicious article on Lady Hazel Lavery.

I am delighted to read the role that she and their gorgeous home played in the Treaty negotiations and her friendship with ill fated Michael Collins. His death made way for the narrow minded and misogynistic De Valera who bowed to the Catholic Church thus creating decades of an oppressive theocracy. This forced so many Irish women, like myself to emigrate, in greater numbers than men, to England.

Thank you.

Played this tribute to Hazel at The National Gallery of Ireland last year.

Also played her musical art-history at Carnegie Hall NY in 2016.

Hazel never enjoyed an appropriate level of official respect for her achievements for Ireland.

It’s about time she did.

Today, while doing research on John Lavery, I came across this successful article. Stories of different women from around the world have always attracted my attention. It was an enjoyable and useful read for me. Thank you.