Quarantines are not without their benefits. During the early months of the pandemic, I was able to reduce my bedside leaning tower of books before it toppled over on my head. Two of the best deal with Northern Ireland. Together they are essential to understanding the conflict.

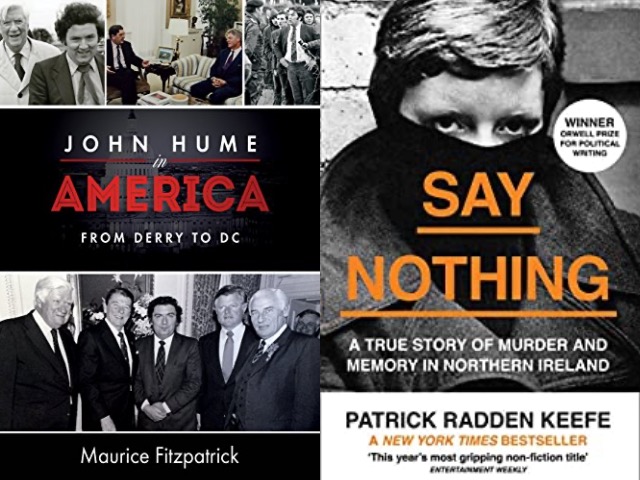

Maurice Fitzpatrick’s John Hume in America: From Derry to DC tells the story of a man who, in the face of death threats and denunciations by enemies and allies alike, stuck to his vision of a peace fair to both sides. In Say Nothing, Patrick Redden Keefe, a staff writer for the New Yorker, renders a meticulously researched account with the momentum of a mystery novel and the relentless respect for facts of an investigative journalist.

The deceptively mild name of “The Troubles” doesn’t do justice to a three-decade war that left 3600 dead, thousands more wounded in body and mind, inflicted untold damage to the economy, revived tensions between Britain and the Irish Republic, empowered sectarian extremists, and squandered Britain’s credibility and prestige in a lawless military campaign. It ended with Her Majesty’s Government and the IRA doing what they swore never to do and joining each other at the negotiating table.

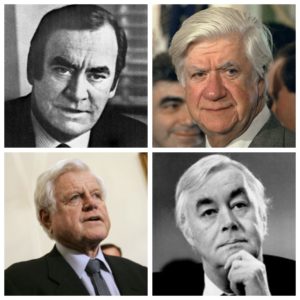

I’m not a totally objective reviewer. I worked as a speechwriter and advisor to New York Governor Hugh Carey, who along with Tip O’Neill, Ted Kennedy, and Daniel Patrick Moynihan came to be known as the Four Horseman. Acting in concert, they employed their considerable political heft to overcome the time-honored Anglophilia of the foreign policy elite, and champion John Hume’s conviction that the only real hope of undoing the stalemate in Ulster lay in admitting a role for Dublin and Washington.

In January 1981, at the prompting of Irish Consul general (and later ambassador) Sean O’hUiginn, I traveled to Derry and Belfast with John Hume. I returned with a far better grasp of the tight spaces in which Hume had to operate. The following month, I attended an off-the-record conference at Ditchley Park sponsored by the British Foreign Office. John Hume spoke for Nationalists and MP Harold McCusker for Unionists. Sir Humphrey Atkins, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, spoke for the government of PM Margaret Thatcher.

John Hume argued passionately there was no realistic hope of ending the conflict without a peace process that included Dublin and Washington. McCusker was adamant that neither he nor his community would ever consent to dilution of majority rule or admit a role for “intruders.” Sir Humphrey restated the tired, century-old contention that North was–and would stay–a purely domestic concern of the UK. The American contingent expressed confidence in Hume’s analysis and reaffirmed its commitment to bring about a diplomatic and economic role for the US.

There were no shouting matches or verbal fireworks. At one juncture, Hume pointed out that the tie Sir Humphrey wore, emblazoned with the symbol of Ulster and the year1607–the founding of the English plantation–was like wearing a tie with 1492 to a meeting of Native Americans. That was about as heated as it got.

Ditchley did nothing to change the equation but confirmed that Irish-America’s political powerbrokers weren’t going to back away, and the person they’d rely on to guide them was John Hume. Without President Clinton’s decisive break with the time-honored deference to Britain’s sole say over the North, peace couldn’t happen. But it was Hume, President Clinton asserted, who showed the way: “He wanted an inclusive peace and thought non-violence was the best way to achieve it. He was the Irish conflict’s Martin Luther King or Gandhi, and I thought he was right.”

Fitzpatrick gives a full, fair, and moving account of Hume’s unwavering belief that peace depended on the terms of the agreement, not surrender. His life was threatened by both sides. His exhausting, selfless, and ultimately successful devotion to lifting the conflict out of the toxic, claustrophobic confines of grievance and revenge never wavered. Without denying or diminishing the integrity, bravery, and determination of the many who worked to bring the Troubles to an end, Fitzpatrick cuts through the complexities to a truth that, while some might dispute or qualify, the facts confirm: “More than by anyone, peace in Ireland was established by John Hume.”

Fitzpatrick and Keefe approach the Troubles from almost entirely different perspectives. Together, like two pieces of a puzzle, they offer a full accounting of the agony of Northern Ireland. Both begin in the 1960s when a generation of young Catholics, beneficiaries of post-war educational reforms and inspired by the civil rights movement in the U.S., demanded an end to years of disenfranchisement and “extraordinary discrimination.” The reaction by the Loyalist majority and the police (RUC) was swift, furious, and brutal.

A peaceful march from Belfast to Derry was ambushed and beaten by a pipe-wielding mob as the RUC stood by. In the summer of 1969, as Keefe writes, “all hell broke loose.” Catholic neighborhoods were invaded and the inhabitants were driven out of their homes. Belfast turned into a battle zone.

Ostensibly sent to restore order, the British Army – in traditional style – acted as an occupying force and worked in concert with the RUC and Loyalist paramilitaries. Internment without trial was imposed, further embittering Catholics. Sectarian tit-for-tat murders and bombings spread. British paratroopers shot and killed 13 peaceful demonstrators. London imposed direct rule.

Fitzpatrick chronicles Hume’s attempt to broker a power-sharing agreement that ensured Catholics a part in governing and acknowledged a role for Dublin. Hume was farsighted and brave. London was shortsighted and back-boneless. It caved to Loyalist pressure. Northern Ireland sank into a suppurating cycle of vengeance and resistance.

At the onset of the Troubles, Keefe reports, the IRA was a shriveled remnant of the guerrilla force that fought the Anglo-Irish War of 1919-1922. In reaction to the inertia of the so-called Official IRA, the Provisional IRA committed itself to an armed struggle whose sole and the immediate aim was to drive out the British and reunite the country.

Tying together Keefe’s account of the IRA’s bloody campaign is the fate of 37-year-old Jean McConville, the Protestant widow of a Catholic husband and mother of ten. In December of 1972, McConville was “disappeared” by the IRA from her flat in a Belfast housing project on suspicion of being an informer.

Displays of savagery such as the dismemberment of innocent Catholics by the Shankill Butchers, or the massacre of Protestant workers at Kingsmill, or any of myriad cruel, callous murders by both sides drew more attention. But in the events that led to her murder and the search for those who ordered her to disappear and those who carried it out, Keefe exposes lies, evasions, and contradictions that echo to this day.

Among those disillusioned by the brutish reaction to non-violent demonstrations were teenage sisters Dolours and Marian Price. Raised in a family steeped in IRA tradition, and part of the contingent ambushed and assaulted on the march to Derry, they were two of the first women granted full membership in the Provos.

They proved skilled, daring operatives. Their innocent good looks gave them a cover their male counterparts didn’t have and masked a steely ideological resolve that led the press to tag Dolours as “One of the most dangerous women in Ulster.” In 1973, the Prices were part of a team dispatched “to carry the war to the enemy” and set off a series of car bombs in London. Two of the bombs went off, wounding hundreds. The sisters were caught, tried, and sentenced to life.

Dolours and Marian went on a hunger strike. They were force-fed and almost died before the government capitulated. Dolours would never resume her role as an operative. But in her time in Provos she developed a close relationship with Gerry Adams. He too came from a family with a long IRA pedigree. Initially a participant in the civil rights movement, he joined the Provos and rose to a leadership position.

Although Keefe notes that Adams was “never perceived as much of a soldier,” he survived beatings, imprisonment, and a near-successful assassination attempt. As a commander, he ordered bombings and shootings that hurt or killed innocent civilians. But while Adams hewed to the orthodoxy of armed struggle, Keefe credits him with insisting “The armed struggle was a means to an end…not an end in itself.”

The hunger strikes that led to the death of Bobby Sands and nine others drew intense international attention. Sinn Féin, the movement’s political wing, was a major beneficiary. In the election of imprisoned Sands to Parliament, Adams saw a way to move from an increasingly futile reliance on violence to electoral politics. He began to circulate the fabrication that he was a member of Sinn Féin but never the IRA.

Fitzpatrick makes clear Hume viewed change as a “cynical shell game” designed to create fear and carnage, then feed off the mayhem. Many of Adams’s fellow Provos were no kinder. Described by one as a “Machiavellian monster,” Adams came to be regarded as a puppet master who kept the hunger strike going after the British were ready to accede to prisoners’ demands in order to stoke growing support for Sinn Féin.

Those who suffered imprisonment shed their blood and invested their lives to expel the British felt deeply betrayed, none more so than Dolours Price. She made explicit her contempt for Adams in a supposedly secret archive of taped interviews amassed at Boston College. Keefe lays bare the fiasco that resulted when, instead of staying sealed until the participant’s death, the British government gained access.

Among other revelations, Price admitted she transported Jean McConville to where she was murdered, and while she didn’t name the killer, she fingered the man who ordered it: Belfast Brigade commander, Gerry Adams. She was dead by the time the tapes were made public.

An accusation based on an interview in oral history was insufficient to try Adams. (In writing his book, Keefe discovered the killer’s true identity.) The long shadow of McConville’s murder fell heaviest on her ten orphaned children. The abuse they endured is a disturbing reminder of the larger toll taken by the Troubles on Catholic and Protestant families alike.

Fitzpatrick and Keefe agree that the long and winding road to the Good Friday Agreement opened up on January 11, 1988, when Hume and Adams began to meet in secret. It was a highly risky proposition for both. When their exchanges leaked to the public, Hume was excoriated for consorting with the terrorists he spent his career opposing. Adams’s critics were confirmed in their conviction he was an unprincipled careerist who used the sacrifices of his comrades to serve himself rather that the cause.

It wasn’t the first time a revolutionary joined forces with a constitutional nationalist to pursue a common end. In the 1880s, John Devoy led the Fenian movement to a “New Departure” that put aside its insistence on expelling the British by force and backed Charles Stewart Parnell’s parliamentary campaign for Home Rule. Both were attacked for comprising the integrity of their causes. Parnell eventually fell. Devoy went on to plot the Easter Rebellion.

The alliance of Hume and Adams turned out more successful. Adams will never be credited with Hume’s idealism. But when the future depended on it, they both proved pragmatists. Despite his d connivance in murder and intimidation, Adams recognized a blind alley. In Keefe’s judgment, “he steered the IRA out of a bloody and intractable conflict and into a brittle but enduring peace.”

Keefe’s and Fitzpatrick’s assessments don’t always agree. But both write with clarity and insight, sort fact from myth, and offer invaluable perspective to anyone seeking a fuller understanding. Fitzpatrick has produced an eloquent and enlightening documentary on Hume. I wouldn’t be surprised to see Keefe’s gripping account–the fullest, fairest account of the Troubles I’ve read–translated into a mini-series.

Time will render ultimate judgment on the policies and persons who perpetuated the Troubles and those who settled them. For the past 250 years, Ireland has experienced periods of peace that turned out to be truces. The Good Friday Agreement presented the opportunity to silence the guns for good. It remains in place, shaky but still standing. Unresolved is the impact of the toss of the dice represented by Brexit. At this point, it’s anybody’s guess whether history will escape the gravitational pull of tribal aggrievement and sectarian hatred or lead to another here-we-go-again moment. ♦

John Hume in America: From Derry to DC and Say Nothing are both available on Amazon.

View Tom Deignan’s Conversation with Patrick Radden Keefe on his new book Rogues: True Stories of Grifters, Killers, Rebels and Crooks.

Peter Quinn’s memoir, Cross Bronx: A Writing Life, will be published by Fordham University Press next month with an intro by Dan Barry.

Have we not heard enough already about the “Troubles.” There is a litany of other historical things which micht be of essence to Irish readers!

Both Hume and Adams were essential for finding a peaceful solution. Hume embodied high level elite politics and Adams mobilized and spoke for the grass roots.

Niall O’Dowd wrote a cautionary review of Keefe’s book https://www.irishcentral.com/news/irishvoice/bestseller-say-nothing-get-gerry-adams-exercise

Politically Sinn Fein has emerged as the leading party in both the north and the south. The idiocy of Brexit is constructing the basis for the integration of Ireland as described in Frank Connolly’s excellent new book, “United Nation”