Lightenings viii

The animlas say: when the monks of Clonmacnoise Were all at prayers inside the oratory a ship appeared above them in the air. The anchor dragged along behind so deep It hooked itself into the altar rails An then, as the big hull rocked to a standstill. A crewman shinned and grappled down a rope And struggled to release it. But in vain. 'This man can't bear our life here and will drown,' The abbott said, "unless we help him.' So They did, the freed ship sailed and the main climbed back Out of the marvelous as he had known it. The Nobel Committee cited this poem.

Seamus Heaney was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1995, “for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past. “

Born on April 13, 1939, the eldest of nine children, to Margaret and Patrick Heaney, at the family farm in Mossbawn, County Derry, the poet remembered his upbringing in his Nobel acceptance speech:

“In the 1940s, when I was the eldest child of an ever-growing family in rural County Derry, we crowded together in the three rooms of a traditional thatched farmstead and lived a kind of den-life which was more or less emotionally and intellectually proofed against the outside world. It was an intimate, physical, creaturely existence in which the night sounds of the horse in the stable beyond one bedroom wall mingled with the sounds of adult conversation from the kitchen beyond the other…”

After attending the local school at Anahorish, Heaney studied at Queens University in Belfast — his father referred to him as a “scholarship boy” — and graduated with a degree in English in 1961. He earned a teaching certificate at St. Joseph’s College in Belfast the following year, and went on to lecture in English at the same school. It was during this time that he began to write, publishing in school magazines under the pseudonym Incertus.

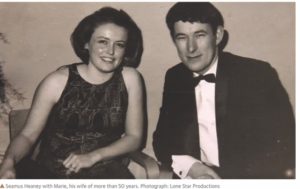

In the mid-1960s, Heaney published Eleven Poems. He married Marie Devlin in 1965, and a year later became a lecturer in modern English literature at Queens University, the same year that Faber and Faber published his collection Death of a Naturalist, which won the E.C. Gregory Award, the Cholmondeley Award, the Somerset Maugham Award, and the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize.

During this period Heaney and his wife had two sons, Michael (1965) and Christopher (1968).

Heaney struggled long and hard with the complexity of the situation in Northern Ireland at the time, and eventually decided to leave his home. “What I was longing for was not quite stability but an active escape from the quicksand of relativism, a way of crediting poetry without anxiety or apology,” he said.

In 1969, his second of ten volumes of poems, Door Into the Dark, was published, and in 1970 Heaney and his family moved to Berkeley, California, where be was a guest lecturer at the University of California. He returned to the North in 1971, but a year later resigned his position at Queens University and moved to the Republic.

“So it was that I found myself in the mid-1970s in another small house, this time in County Wicklow, south of Dublin, with a young family of my own,” Heaney said.

In 1972, Heaney published Wintering Out, and the following year, his daughter, Catherine, was born. During this period, Heaney won many awards, gave readings in England and the U.S., and edited two poetry anthologies. He began teaching at Dublin’s Carysfort College in 1975, and six years later took the position of visiting professor at Harvard University. Three more collections of his work were published during this time — Field Work, Selected Poems and Preoccupations: Selected Prose.

By 1984, Heaney’s Station Island had been published, and he had been elected the Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard.

The deaths of his parents — his mother in 1984 and his father in 1987 — had a great influence on Heaney’s work, and were reflected in The Haw Lantern and Seeing Things. His series of sonnets, titled Clearances, were written as a memorial to his mother.

Although Heaney has not lived in Northern Ireland for some 25 years, there has always been a link between his writings and the tragic situation which plays itself out there, and it seems only fitting that lines from his 1990 play, The Cure at Troy, should come to embody the hope of a nation in the wake of the IRA and loyalist ceasefires in 1994.

“History says, Don’t hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme.”

In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Heaney spoke of “poetry’s power to do the thing which always is and always will be to poetry’s credit: the power to persuade that vulnerable part of our consciousness of its rightness in spite of the evidence of wrongness all around it, the power to remind us that we are hunters and gatherers of values, that our very solitudes and distresses are creditable, in so far as they, too, are an earnest of our veritable human being.”

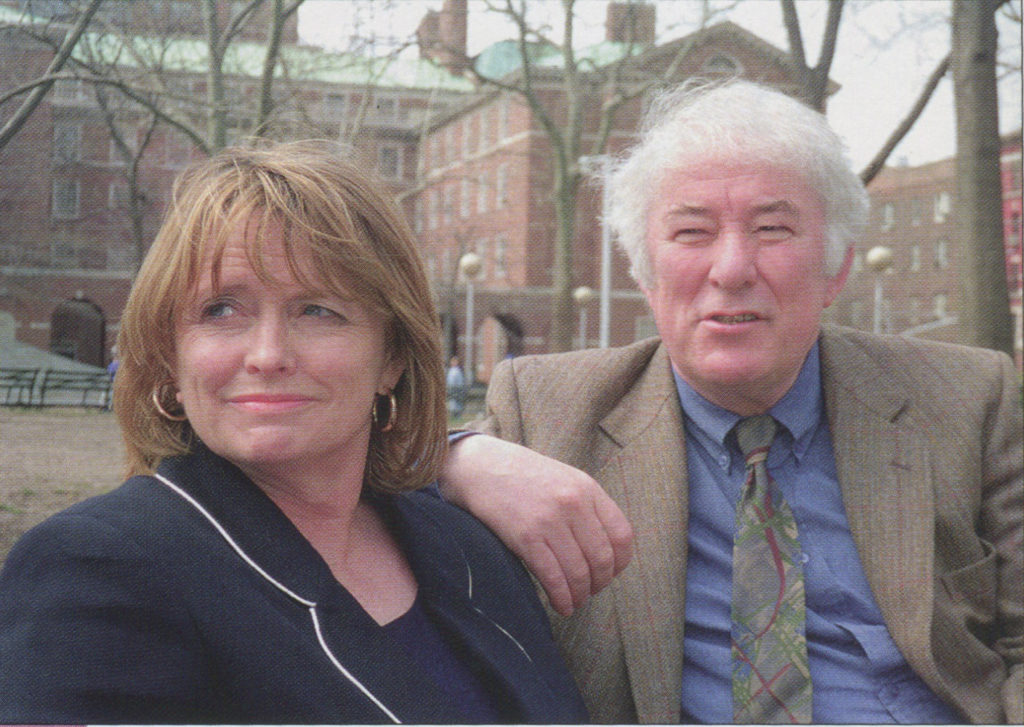

Irish America’s Patricia Harty spoke with him in New York on April 13, 1996.

IRISH AMERICA: How has winning the Nobel Prize affected your life?

SEAMUS HEANEY: It hasn’t changed my life, it has intensified aspects of it. Over the last ten years, the demands to give lectures, to be present at cultural events, to open exhibitions, to do social and cultural duties — all of the things that come with the business of being a writer — have multiplied drastically. So luckily I had got myself set up to deal with all that. I have a place [in Wicklow] where I go to get away from it. Marie and I do have privacy at home [in Dublin] because the decorum of people is magnificent. There’s acknowledgment and recognition, but a minimum of intrusion.

Of course, something has changed because the word Nobel is like a magic wand that is waved over you. But the actual day-to-day is just more busy, busy, busy.

I.A.: What does it mean to call yourself a poet?

S.H.: I think if you call yourself a poet it means that you live by it, so to speak, and for it, in a very serious way. There’s a phrase of Ted Hughes which I like very much. He said that the true poem emerges from the place of ultimate suffering and decision in us, and I think if you call yourself a poet, you publicly consecrate yourself to living somehow by the places of suffering and decision.

I.A.: How does it feel to have the world reflect back at you that yes, indeed, you are a poet?

S.H.: I think the discipline which writers must perfect is the discipline of doubting the world, the discipline of self-knowledge and self-castigation. Certainly, the activity should induce a sense of vigilance — it’s a kind of spiritual exaction to be a writer. But the answer is that I accept the recognition in good faith.

I.A.: I find that reading your poetry can sometimes evoke painful memories. Is the creation itself painful?

S.H.: No, the creation of it is pleasurable. I’m sure that Beckett enjoyed doing his most painful work too. I think the sine qua non of the activity is some form of joy in the actual doing — it’s the bringing into alignment of the form, of delight and expression, bringing that together with the actual endured reality of life that gives you the balance. Take a novel by John McGahern where there is a kind of undertow of suffered life and a certain desolation, but there’s also the cello music of the writing itself. Composition is a pleasure when it’s going right, but when it’s not working it’s just sheer agony because then you’re having the dry hoaks.

I.A.: Did you always have an instinct that this was what you wanted to do?

S.H.: I didn’t have an instinct, no. When I look back on that long ache that was my adolescence (and everybody else’s adolescence) I realize that I certainly had some artistic yearnings. I had a real desire to be able to play music, and I remember just wishing — there was no resentment here, by the way — wishing for access to music, to be able to play the piano, maybe. I was also in my late teens and early 20s working with marquetry — making pictures from wood and so on — so there was some desire for artistic expression.

“Writing poems did give me a sense of myself, it verified something in me. There’s a psychic verification that artwork performs for the artist, and gradually I realized that writing was something that I could do.“

I.A.: What was it that allowed this talent to flourish?

S.H.: Acceptance early on by editors I didn’t know when I was totally unknown myself. My first poems were written in — obscurity is the wrong word — just nowhereness. Obscurity somehow implies that you are being kept out of the light.

I was in a flat in Belfast, I had no literary contacts, but I had aspirations. And the fact that the poems were accepted by the Irish Times, Kilkenny Magazine, and the Belfast Telegraph in three months was terrific. Publication for a young writer is a crucial transition, it’s a rite of passage. You go from the unwritten state to the slight mystery of seeing your name in print. I was very lucky in that even my book was sent for, I didn’t have to tout it. Faber, before I had a manuscript ready, wrote to me.

I.A.: How did that change things for you?

S.H.: When your book is published and then well-reviewed, and you have created a textual creature with the same name as yourself and it’s recognized as a reflection of you, then you begin to be discussed as that creature out there. Now, at the beginning that is gratifying but gradually, it becomes haunting, and you have to develop a second relationship with that doppelganger, one of nonchalant indifference. In fact, you have to eventually discover a place to live completely separate from it — to let him continue his life in the world. That’s where I am now.

I.A.: Is it affecting you now?

S.H.: Yeah, I have to continue in spite of it, you know? But it’s not, as my mother used to say about pregnancy, a killing condition.

I.A.: Can you tell me about your mother?

S.H.: My mother was very strong — very unrufflable, steady on the emotional keel. Righteous and majestic and vulnerable, her McCann family were terrific, they had the volubility of protest — they were democrats. My father had a different kind of majesty, the country farmer’s silence and hauteur.

My mother had an unbending thing which she shared with women of that generation, a child a year in 8, 9, 10 years. The giving-birth factor involved, I suppose, a wilful adherence to the compensations of Catholicism — the cult of the suffering mother of Jesus, the cult of the suffering Jesus, and the cult of St. Anne, the mother of Mary. These were actual real psychic resources for sublimation in the lives of women. In particular, for ones who were going through, without much consolation or understanding, the solitude and exhaustion of childbirth and child-rearing and the biological entrapment of being in a place with no birth control. Nowadays I remember that affirmative bold outcry of prayers from women in church as a cry of rage and defiance. My mother wouldn’t have put it that way — she would have seen it as a form of transport and endurance.

I.A.: Was it hard being a different type of man than your father?

S.H.: Well, I suppose there are two answers. It was not at all hard socially, because there I was the scholarship boy, going to boarding school, and that path was mapped out. My father would just have said, “The teachers say he’s a smart chap.” Now, my father never, never advised me about anything, but I had a sense of his vigilance, his instinctive judgment — not judgmental, more concerned and wise. He had protective care. After I reached the age of 14 or 15 he just assumed that I would choose my path, so there was no difficulty. Any difficulties were actually of the species rather than the biography — of sons growing up and fathers being there. It’s a Freudian generality I suppose.

I.A.: How did you manage to break with tradition and leave the farm?

S.H.: I never actually experienced it as a break. Whatever your background, poetry is always going to be an extra-ness and a strangeness. Each poet is alone with his or her chances at the end as much as at the beginning. In some way, the farm background is like a mythic possession; you know what neolithic life was like if you have known rural life in pre-modern Ireland. And that is a great creative resource. A kind of dream knowledge. I mean, creative is such a cant word, it’s just the ability to make something of the game — to keep moving it along, wakening it up and shifting it. Joseph Brodsky said a marvelous thing about poetry, that it wasn’t merely an art, it was an anthropological necessity because it prompted new possibilities for the destiny of the soul.

“If a poet publishes a poem in a newspaper in Ireland the judges will read it, the afternoon drinkers in the pub will read it, the Taoiseach will read it, the Protestant bishop will read it, the Catholic bishop will read it, the hostesses will read it, the gossip columnists will read it, and the name of the poet will be a possession.“

I.A.: Were you surprised at the poem that was cited by the Nobel Committee, “Lightenings”?

S.H.: You mean the one about the monks at Clonmacnoise having the vision of a boat in the air above them? I was delighted with that because the thing is a kind of image of poetry itself. It’s about the negotiation that goes on in everybody’s life between what is envisaged and what is endured — between the dream up there and the doings down here. It has the mysterious purchase of a good story but also it’s pregnant with suggestion. I think it’s about poetry, maybe that is why they cited it.

I.A.: There seems to be something in the Irish that makes them partial to poetry.

S.H.: There’s a tradition, a value system which is given, a historical myth or truth that predisposes us as a community and as individuals to trust in poetry. It’s a reality, there’s no doubt about it. If a poet publishes a poem in a newspaper in Ireland the judges will read it, the afternoon drinkers in the pub will read it, the Taoiseach will read it, the Protestant bishop will read it, the Catholic bishop will read it, the hostesses will read it, the gossip columnists will read it, and the name of the poet will be a possession. I think it’s a matter of some indifference whether they are equipped in any special literary way to read or judge poetry. We are talking about the actual role of the poet in society, and in Ireland, there is no doubt that that role is alive and it contrasts vividly with what will happen if a poet publishes a poem in the Times of London, or in the New York Times. So fearful as I am of talking up romantic notions about Ireland, I think you have to concede that there is a public, psychic and artistic reality in this which is a genuine positive cultural possession of the country.

I.A.: You are the first Irish Catholic to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. How important is Catholicism to you?

S.H.: I realize now that from the age of dawning of consciousness to the age of reason, or from about six months to age twelve, I was totally immersed in the religious sense of the world. In the world I grew up in, the mass was the social event of the week. The priest was one of the ruling class. And then when you went to college, you were really dealing with a mini-Maynooth. The whole sense of morality, right and wrong, everything was based on Catholicism, and it continued when you went to confession, weekly or monthly, (in college it was communion daily), right through till your early 20s and the next drama of consciousness began as you started to secularize yourself in response to the world.

Obviously, I could talk until the cows come home about the minority status of Catholics in the North of Ireland, but that ground has been gone over a lot. I would say that the more important Catholic thing is the actual sense of eternal values and infamous vices that our education or formation gives us. There’s a sense of profoundness, a sense that the universe can be a shimmer with something, and Catholicism — even if I don’t like sentimentalizing it — was the backdrop to that whole thing. The world I grew up in offered me a sense that I was a citizen of the empyrean — the crystalline elsewhere of the world. But I think that’s gone from Catholicism now.

I.A.: You led a double life in that in addition to writing you also taught school. How did you manage both?

S.H.: I never conceived of a way of life where my writing vocation would actually be my whole life. This may have been a mistake — I’m talking now about a given ethic or attitude, one that I didn’t deconstruct in myself. In the world I came out of — and it was inside me from the beginning and almost to the end — the general idea was that you worked for a living. You earned your keep, you asked for no special favors and you then prayed that grace would visit you. Laboring at your job doesn’t infuse you with the grace of poetry, but I thought of them as two separate things — one is the mystery of gift, and the other is getting on with it, conducting yourself as a citizen. I certainly didn’t think that if you were involved with the mystery of writing you had any right to expect better treatment or any special status as a citizen. That was solidarity, I suppose, with the kind of unliterary life that I lived in the beginning. And then while I was teaching there was a desire to prove that poetry wasn’t effete or a betrayal of loyalty to humble origin. So my teaching at school was a defense of poetry as part of the fabric of the usual life. You demystified it, you toned it down and you called people towards it by saying: “look, it’s quite simple.”

I have now come to realize that this too is misrepresenting things and that you should stand up for the strangeness, the otherness, and the challenges of this stuff. Whereas at the beginning I was more interested in bringing an audience towards it and calming their nerves, now I’m more interested in saying, “Down on your knees, this is the goods!”

I.A.: Did you enjoy teaching?

S.H.: I never enjoyed thinking about it, but I actually enjoyed doing it. It takes a long time for teachers to get over their self-preoccupation — will I be able to do it? People underestimate the sickening dread that can be in somebody as they stand up on a podium to begin a class. It’s hard for me to do a lecture course to this day. I’m tense and I’m worried and I’m up early preparing it. So the answer to the question is ambivalence. I enjoy doing it when I’m doing it but I don’t enjoy thinking about it.

I.A.: In terms of your own writing; are you very disciplined or do you wait for the muse?

S.H.: I’m not very disciplined, no. I’m half disciplined. I’m not a person who gets up every morning at the same time and sits at a desk and plunges into it. Prose writers have to do that. On the other hand, the older I get the more I feel that you should peg out a pitch and provide space for the game to be played, mark out a landing place for the muse if she wants to come down. So time, time alone, when the pages are in front of you, or you’re reading, time is what’s important. In the beginning, I used to say to myself anything that’s worthwhile forces its way through. And to some extent that’s true. But my life has become so besieged with different responsibilities…

The last decade and a half of lecturing and teaching at Harvard and Oxford — it’s also just a matter of growing older — the world places many, many demands on you so you have to be wary and in resistance to it and secure a space where poetry can come through. My redemption has been Wicklow, the actual house is 45 minutes from my Dublin home — it’s both a physical reality and psychic image of retreat. When I go there I feel gathered and safe and undercover.

I.A.: After the ceasefire was announced you wrote that you felt 25 years younger, but you were angry also at the 25 years of loss. You mentioned the inroads that were being made before the violence when both traditions were finding “room to rhyme.”

S.H.: I felt that a whole set of nascent politics has been obliterated from memory by what happened. There had been something in the air — it was the 60s taking on a special shape in Northern Ireland. There was a political shift. This much younger generation of unionists was coming along — God knows they wouldn’t have been ideologically soft — but they had a social conscience of a different sort.

But I think the other thing that happened to me after the ceasefire was some kind of anger that I had suppressed in myself for years. It wasn’t anger at any one person or group, it was just the conditions — there’s a poem in The Spirit Level called “Mycenae Lookout” which is written from the point of view of the watchman during the Trojan war, and it was written out of this feeling. I always wanted to write about the watchman and I now realize that this poem is angry.

I.A.: How do you feel now?

S.H.: Obviously I think that the British government has been thick-witted and caught in a cultural and political posture that they can’t shake. I thought that the two months after the ceasefire offered a moment of genuine historic possibility that everyone expected Major to grasp. Reynolds and Hume were grasping the hand of Adams — they actually deliberately and tactically said “Let’s go.” And of course, Major hesitated and then hesitation became funk. But for a while, a possibility that had lurked in the political unconscious of the unionists allowed itself into their consciousness. They were aware that some change might be about to happen, and if that moment had been grasped history would have moved along. Now all that is past and I think that is the real tragedy of it. Now we’re just in the realm of mess and while the mess is admittedly preferable to atrocity, I think it’ll drag on tediously, demeaningly. It’s just the usual tactics of politics, hacking it out along party political lines; they harry each other from the touchlines of their own positions. It’s so exhausting for the citizens and it’s so unpromising, but it is the usual. I don’t think anything will be quickly resolved, everything will be messily deferred and deferred.

I.A.: Did you have regrets about leaving the North?

S.H.: No, I’ve no regrets. It was actually transitional at the time I left — I had to make a move.

I.A.: Do you feel like James Joyce who went off into exile?

S.H.: Well, he went off in dudgeon. I didn’t leave in any form of dudgeon or resentment, I left because of a desire to be freer within myself, or simply to be more alone. This was not political, this was artistic and domestic. Moving to Wicklow was a crucial moment. Our own lives (I mean Marie’s life as well as mine) were reconstituted emotionally by going into a lonely place together. And it was very fortifying for the two of us. You took the measure of things again and started up again.

I.A.: Tell me about California.

S.H.: They were the best years of our lives, 1970, 1971, very important. It was the first time we had lived outside of Ireland, and Berkeley was a place of great promise and merriment. A place of reorientation after Belfast — Belfast that was so radical, so downbeat, so corrective of any form of flourish — it was great to go to California where flourish was encouraged, where instead of refusal and irony there was an indulgence. It was like going into a hot house for the spirit.

I.A.: Did you ever think of staying there?

S.H.: Never, no. But I loved California, partly because it was such a helpful year for us.

I.A.: Do you think it’s essential to your poetry to live in Ireland?

S.H.: I don’t think it’s essential but — I don’t know the answer. The last 25 years have been so stressful and crucial it would seem to me that I couldn’t have knit myself into something workable without staying in Ireland.

I thought that the two months after the ceasefire offered a moment of genuine historic possibility…and if that moment had been grasped history would have moved along. Now all that is past and I think that is the real tragedy of it.

I.A.: Do you still see yourself as a citizen of the North?

S.H: The image I have is of the ripple going out, which is an image you can find in Joyce’s work: for him it was Sallins, Kildare, Ireland, British Isles, Europe, the universe — for me it was Derry, St. Columb’s, Queens, Berkeley, Wicklow, Harvard, Oxford, it’s the same sort of ripple. There’s a part of you that’s still an extension of the original self-moving at the circumference of your adult cognition and realization. There’s something out there that is actually continuous with your first awareness. Your consciousness is such a strange, strange thing, it’s hard to talk about the inwardness of it — it’s both fixed from the beginning and yet at the same time it’s capable of taking in experience and newness. So I see myself as a big set of ripples because if you look at the ripples in a pool when the stone is first thrown in you can see them going out in big rings, but then at a certain point, it looks like they are also going in towards the center. The circumference represents some form of knowledge. On the other hand, you always have to work with that which was there at the core from the beginning. I’m still writing about that. It’s just that your perspective on your imaginative possessions changes. Your perspective on your cultural and emotional possessions changes. This negotiation between the center and the circumference, that’s where I live anyway. ♦

This interview originally appeared in the May/June 1996 issue of Irish America.

Thank you for the depth of this wonderful interview.