“This is the most important musical of our times”

go see Paradise Square for the best blending of Irish and African-American dance you’ve seen; the most inspiring, stand-up-and-cheer vocals you’ve heard; and a story about a part of American history you’ve never heard.

“What really blows this show out of the park is its knockout dancing, and the brilliant choreography by Bill T. Jones that in many ways is more potent than any spoken dialogue as it sets the phenomenal rhythms and moves of both Irish step dancing and African juba into a brilliant competition that reveals the genius of both ‘languages,’” critic Hedy Weiss wrote for Chicago’s PBS affiliate.

I’m going to give away one of the funniest lines in Paradise Square. But there are so many more reasons why you should go see this work of art when it opens on Broadway in March, it’s hardly a spoiler.

Young Owen Duignan steps off the boat from Ireland to greet his Aunt Annie in New York and she tells him she has married a protestant. Upon seeing his uncle is a Black reverend, Owen exclaims, “Oh he’s THAT kind of protestant!” and gives him a big hug.

Owen’s emotion is one of relief. His aunt has not married one of those heartless British landlords he knows the word “protestant” to mean. She has married a fellow member of the oppressed.

“Owen’s never seen a non-white person – the Irish are not considered ‘white’ by American standards at this point,” A.J. Shively, the Irish-American actor playing Owen, said.

Black 47’s Larry Kirwan’s epic Paradise Square unearths a buried treasure of American history before the Irish became “white,” when the near-penniless Irish joined equally struggling African-American escaped slaves and freeborn-but-still-oppressed Black Americans in the slums of New York’s Five Points during the Civil War.

A century before Archie Bunker was symbolizing small-minded white ignorance and intolerance of Black people, they and the Irish were living, dancing, singing, inter-marrying together in New York, and that gloriously comes alive on stage in Paradise Square with rising star Joaquina Kalukanko’s strong vocals and choreographer Bill T. Jones’ lively blending of Irish and African-American dance.

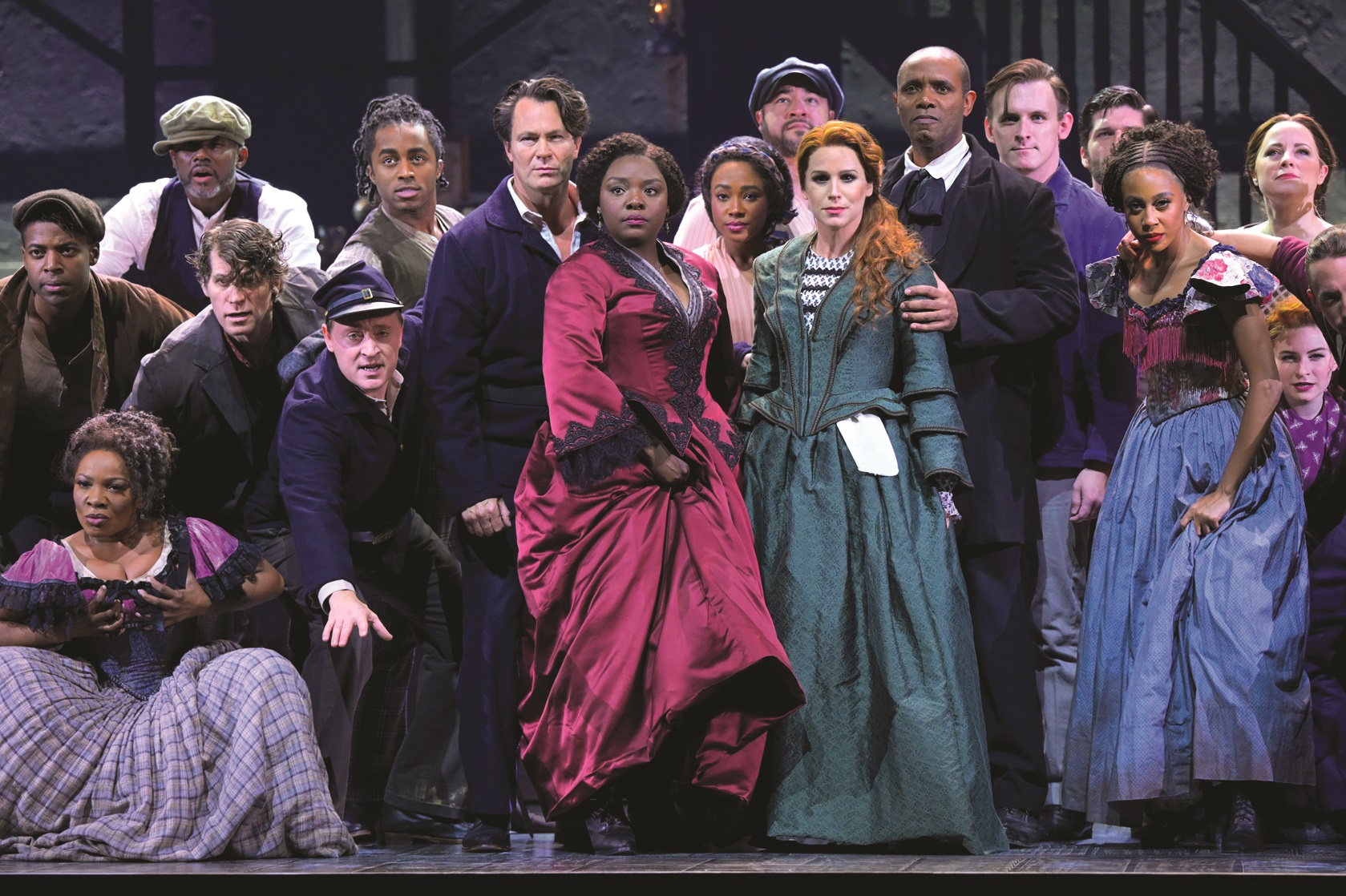

Eilis Quinn and Chloe Davis with the ensemble cast of Paradise Square (Photo: Kevin Beirne)

A post-COVID Broadway reopening

So many years in the making from Kirwan’s original Hard Times show 8½ years ago; to being reworked by three other writers, Christina Anderson, Marcus Gardley, and Craig Lucas; taking it up to producer Garth Drabinsky in Toronto…” (Drabinsky served a prison sentence for fraud and forgery in Canada but retains his reputation in theater circles as a legendary and sought-after producer) – “So many people have added so much over the years,” Kirwan said; to premiering at the Berkeley Repertory Theater in California in January, 2019, till Covid-19 struck and all of American theater largely shut down for two years.

So with audiences masked up and required to present proof of immunization, Paradise Square is allowing musical theater to come roaring back.

“Audiences are comfortable being in large spaces again,” said Broadway veteran Nathaniel Stampley, who plays Owen’s uncle Rev. Lewis, a conductor on the Underground Railroad. “We’re grateful for the vaccinations. We’ve had a lot of energy and art stored up for 18, 19 months. A lot of that is spilling out on the stage now.”

The critics have raved about the show’s one-month launch in Chicago, which finished in December as the actors and crew packed up and moved the show to Broadway’s Barrymore theater.

“This is the most important musical of our times, drawing from American history to depict the kind of racial harmony we still call aspirational, as well as the path to its destruction,” Brian Hieggelke wrote in Newcity. “If you’re a fan of the kind of big, dumb musicals that too often make bank on Broadway, this is not your show. It’s smart, nuanced and jammed with ideas about race, gender, class, immigration, the neglect of veterans, and just about everything else that ails America. Pretty Woman this is not.”

The musical is “shaped by visually lush, emotionally intricate storytelling largely created through Bill T. Jones’ vivid choreography and Jason Howland’s gripping score,” Catey Sullivan wrote in The Chicago Sun-Times.

“The singing is blockbuster, the dancing is dazzling, and the reckoning that anyone sitting through this fable must undergo is as sobering as it ought to be,” Irene Hsiao wrote in The Chicago Reader.

Some criticism directed at the show say the writers try to tackle too many issues – race relations, immigration, the Underground Railroad, etc.

So critics in search of simplistic, underachieving plays and who have trouble holding more than one plotline in their head at a time might want to skip Paradise Square. (Did they think Lin-Manuel Miranda tried to tackle too many words in Hamilton?)

“Some shows are purely about the sets, the costumes – this is a very human story. Not all musicals are created equal,” Stampley said.

Chicago Theater Review thought the creators and performers of Paradise Square weaved all these converging forces together just fine.

“Paradise Square is a magnificent show,” Colin Douglas wrote in the Review. “It’s stuffed with a great deal of historical information, as well as some soul-searching examinations of racial, class and gender equality. Immigration issues feature heavily in the musical’s storyline, along with how America has sadly neglected its sick, downtrodden and veterans of war. This is a musical for audiences who enjoy great music and majestic choreography, but who also prefer a show that makes them think and feel.”

Racism, anti-immigrant bias persist

The villain of the movie, political boss Frederic Tiggens, sees the alliance of Irish and Black people threatening his ability to exploit both groups so he whispers in each group’s

ears that the other group is the source of their problems, helping provoke the Draft Riots that will burn the community down and kill the brief-lived “paradise” of racial harmony.

Is it fair that you come back from fighting the Civil War and a Black man has your job? Tiggens asks the Irish Civil War vets. “If I had to pay the coloreds the Irishman wage I’d be ruined,” one of Tiggens’ business-owner supporters laments.

A political opportunist scape-goating immigrants and minorities to advance his career? Could that have any relevance to modern America?

“These things keep repeating themselves over and over and over again, and we are asking ourselves: When will we ever learn?” lamented Irish-Canadian actress Chilina Kennedy, who plays Owen’s Aunt Annie, and who previously played Carole King in Beautiful on Broadway.

“It’s pretty remarkable about how much has changed but how little has changed,” A.J. “Owen” Shively agreed. “I went to Ellis Island when the migrant caravan was the big news story and it was literally, word for word, the same newspaper headlines – just substitute the word ‘Italian.’”

The message comes through in the play, Kirwan said. “It’s always happened. You’ve always had the race-baiting. It just takes someone to do it skillfully. It’s not going away. This will continue as long as you’ve got opportunist politicians who will work it, use it,” Kirwan said.

Story found in old etchings

So where did Kirwan find this story that had been lost to us for so many years?

Kirwan’s grandfather who raised him on a farm in Wexford talked about an old childhood friend who moved to America and never wrote because, his grandfather told him, “He must have gotten lost in The Five Points.”

“I was living on the Lower East Side. I was broke. I was walking distance from ‘The Five Points.’ I spent a lot of time in the second-hand book stores around 3rd Avenue,” Kirwan recalled. “One day I came upon a book with some etchings of scenes of the dance halls in The Five Points. Looking at the faces of the dancers, it was usually an African-American man and an Irish woman. They were clearly in romantic relationships. There was a joy and a delight on the faces of the dancers that beamed across the centuries.”

As a musician, Kirwan already knew that Irish and African-American musicians got together at the dance halls, forming new genres of music from the mixture of the two musical styles, as well as dance. Tap is thought to have originated in The Five Points.

“Usually, you’d have an Irish fiddle-player, an African-American banjo player and percussionist, an Irish singer,” Kirwan said.

He started researching the inter-racial dating in the mid-1800s. The flood of young women coming from Ireland during the famine arrived with little money and little oversight.

“The whole social system had broken down. The priests did not come to America with them. The parents did not come either. They could do what they liked,” Kirwan said. “The best places for the craic were the African-American dance halls. African-American men were gentlemen to them, danced with them. They liked to dance. Before long romance started. There was no one there at home to say ‘No’ to them.”

There was a word for these young lovers crossing racial boundaries: “Amalgamationists.”

“These amalgamationists were despised by the uptown protestants,” Kirwan said. Anti-Catholicism was virulent at the time. And while Black residents of New York were not enslaved, the “uptown protestants” hardly welcomed them as equals.

“When the famine Irish arrived here, African-Americans were already well-established in the Five Points, a few steps up the ladder from the immigrants,” Kirwan said. “African-Americans were the only ones that took the Irish in. The pre-famine Irish were ashamed of the famine Irish. They had worked their way up the ladder. They were becoming ‘white.’ And now thousands and thousands of these diseased people are coming in…”

And so the Irish and African-Americans found each other in the Five Points.

“It makes sense that there would be a blending and mixing of these two cultures,” Nate “Rev. Lewis” Stampley said. “No one would ever say that these two groups of people are shy or timid in any way. That mix is what makes this country really special.”

Intermarriage between Irish-Americans and African-Americans in the Five Points peaked from 1845 to July 13, 1863, the day the Draft Riots started, Kirwan said. Mobs of white people, including Irish, “Burned down the African-American dance halls, and the mixed families scattered to New Jersey and Staten Island and kind of got subsumed into Black culture,” Kirwan said.

As Chris Jones put it in The Chicago Tribune, “Black Americans and Irish immigrants lived, mixed and intermarried so thoroughly and vivaciously as to not only percolate American cultural forms like tap and jazz, but, for a brief but shining moment, to mutually create an idealized image of what this nation could always have been. All before forces terrified of the political power of these two aligned groups decided it must not stand and took paradise down and paved it into a parking lot.”

Can we reclaim Paradise?

Can Paradise Square be our wake-up call to remember we were on a better track 160 years ago and find our way again to racial harmony in the United States?

Looking at the white supremacist march in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017, George Floyd’s murder and the demonization of Americans who marched to honor Floyd, it’s easy to overlook the progress that has been made on race relations in the United States since the 1860s.

In the century and a half since the Draft Riots, Americans have elected and re-elected a Black president born to a white mother with Irish roots and an African immigrant father. New Yorkers have elected two Black mayors and a white mayor married to a Black woman. Chicago is on its third Black mayor, this one a Black woman married to a white woman.

So is any of this even remarkable anymore? Are we living in the paradise that Kirwan’s characters dreamed of?

“We describe our saloon as a little bit of Eden. There are little bits of Eden in all 50 states. There are large portions of us that are living that way now,” Stampley said. “We can create the kind of future we want. We can all strive for something better. I am grateful to be a part of that change. I am doing my part by being in this play.”

“I think it’s kind of the blueprint – a ‘future yet to be,’” Kennedy said. “It’s this kind of perfect… Well, not perfect. It has scars and traumas. But the way that the two cultures blended together and respected each other – that hasn’t quite happened yet in America, or in Canada either.”

“1863 was the worst possible time in U.S. history,” Kirwan said. “People actually owned other people in this country. Don’t tell me nowadays that we’re going through this awful time. If amalgamationism can happen in the midst of all that, we can all reach out to each other and agree to disagree with each other. Hopefully, Paradise Square will help in that fight, bring Irish and African-Americans together.”

Just watching the cast – 18 African-American and 18 white actors – interact with each other on and off the stage gives Kirwan hope, he said.

“The Black and white people on the stage are totally at ease with each other and you don’t see that in society much,” Kirwan said. “They all go out afterward together. You don’t see clumps of black people and white people. That’s the culture we’ve created in Paradise Square.”

Kirwan, Kennedy and Shively grew up in very white environments in Wexford; New Brunswick, Canada; and Dublin, Ohio, respectively. Stampley grew up in a Black neighborhood in Milwaukee. They and the other cast members all feel pretty comfortable with each other now, they said.

“It’s hard to get out of your box unless you spend time with other people,” Kennedy said. “We all hang out together all the time. That’s part of what I love about the show – it does bring us together. We have a lot of wine and we sit around and talk. There’s a boldness about the United States that I love. Kind of allows for debates. [In Canada,] it takes a little longer to get there. People are very polite, very careful. It’s more difficult to have intense conversations.”

Stampley has enjoyed the cast’s discussions with Thulani Davis, an African-American playwright, journalist and scholar in residence at Stampley’s alma mater, the University of Wisconsin at Madison, who was brought in to serve as the “dramaturg” for the show, providing historical and factural context for the setting.

“We have a community of actors where we are together and there’s a larger political dynamic that was playing out on a national level, licking our wounds of the last 4, 5, 6 years of all the strife, and then, the coronavirus,” Stampley said. “It has made us all very vulnerable, very open to each other’s history and perspective. It’s been a really special time to be together. I look forward to learning a lot more about the Irish-American heritage in this country and how it has influenced so many other things.”

“All it takes is for people to listen to each other,” Shively said. “Last summer (George Floyd) was another moment of all of us, being American, trying to find common language so we can speak to each other. I have hope people are able to be more patient than they’re being right now. You have to have optimism.”

At center, Kevin Dennis (with cap), Matt Bogart, Joaquina Kalukango, Chilina Kennedy, Nathaniel Stampley and Ensemble in Paradise Square (Photo: Kevin Berne)

Dancing “like there’s fire on the floor”

Put all the serious subject matter aside for a moment. Paradise Square is a jubilant, joyful musical that celebrates African-American and Irish music and dance and their coming together to form new American music and dance.

The Tribune’s Chris Jones writes, “The show has a star turn from Joaquina Kalukango that will be formidable competition for anyone and everyone come Tony Awards time.”

Kalukango’s climactic “Let it Burn!” repeatedly brings the audience to its feet for standing ovations at an awkward moment when you want to cheer her commanding performance while not appearing to condone the rioters burning down her building.

“It’s hard to cheer and yell with a mask on. But that I did right along with the entire crowd at Paradise Square, as Joaquina Kalukango delivered a shatteringly powerful show-stopper, ‘Let It Burn,’ holding the audience in her thrall for every second,” Bill Esler wrote for Buzznews.

“We’re talking Jennifer-Hudson-in-Dream-Girls caliber, perhaps even better. Really!”

Kalukango was a Tony nominee in 2020 for Slave Play. Watch for the Tonys to notice her and possibly other cast members for their vocals and their dance.

“Bill T. Jones’ choreography is outstanding. This is the kind of dance that wins Tony Awards,” Rachel Weinberg writes for Broadway World. “It’s beautiful. In Jones’s choreography, Paradise Square’s blend of different cultural influences finds its seamless match. The choreography is fantastic, and the ensemble dance numbers are breathtaking.”

Owen shows off his Irish dancing as Washington Henry, played by Sidney DuPont, struts his African juba. That swings back and forth from competition to collaboration back to competition. They respect each other. They learn from each other. They compete with each other.

“Both can dance like there’s a fire on the floor – Owen with the sprightly, high-stepping patterns of the Irish, Washington Henry with the grounded stomp, slap, and roll of African American juba,” Irene Hsiao wrote in The Chicago Reader.

“There is some ridiculous Irish dancing in this – not from myself, but from the world championship Irish dancers. There is some great music and rhythm,” Shively said, greatly under-selling his abilities and praising the coaching from choreographers Garrett Coleman and Jason Oremus. Shively is paired up with more practiced Irish dancers for many of the acts.

It’s not Tom Cruise in Far and Away

Irish fans can be pretty particular about American actors attempting Irish accents. So how do these Yanks (and Canadians) do? Well, Shively and Kennedy admit they don’t sound like Liam Neeson and Saoirse Ronan, but they and their fellow cast members make it clear they practiced, listened to their dialect coaches, put their hearts into it and they pull off a respectable effort.

Kennedy said she tries not to slip into the Newfoundland/Nova Scotia/Prince Edward Island accents she grew up around.

Growing up in the Irish-named town of Dublin, Ohio, which boasts one of the largest Irish festivals in America but is not home to many Irish immigrants, Shively said, “The accent is not in my ear. You could hear the music. The first concert I ever went to was the Cranberries. With any accent, it’s not the vowel shapes and sounds, it’s the music of it, thinking why a culture speaks in a certain way.”

Shively watched the scene in the movie Brooklyn in which Saoirse Ronan’s character serving dinner in a church basement hears Iarla Ó Lionáird singing a traditional Sean-nós song in Irish.

“That music resonated in my DNA – I could feel it in the center of my being,” Shively said. “I listen to as much of it as I can, I took lessons at the Irish Arts Center of New York.” He studied the Irish language to get the sounds. The effort shows in his singing, his dancing, his anguish about the threat to draft Owen so soon after he’s arrived from Ireland.

An imperfect “father” of American music

Stephen Foster, called by some “the father of American music,” makes more than a cameo appearance in this play.

Owen and Washington repurpose some of his best-known songs like “Camptown Races” for their dancing duels.

The African-Americans take him to task for appropriating their voices, the songs they used to endure their hellish slave labor, and making them happy sing-song numbers, as though being enslaved could ever be happy.

Foster really did hang out in the African-American dance halls in those times because he knew that was where innovation in music was going on, Kirwan said.

Foster’s early hits like “Camptown Races” and “Oh, Susanna” “were steeped in race-baiting minstrelsy,” Kirwan said. “He abandoned this genre, thus beggaring himself, but will always be tainted by his brush with the Peculiar Institution [slavery] though infinitely less so than slave-owning presidents like Washington and Jefferson. He did seek to create a ‘new American music,’ fueled by immigrant sensibilities and was on track to doing so with such compositions as “Beautiful Dreamer” before he died penniless at the age of 37, six months after the Draft Riots of 1863.”

Foster’s role was bigger in earlier versions of the play. Some critics cite Foster’s appearance as one of the complicating sub-plots they would like to see removed from Paradise Square to simplify the play.

I hope that doesn’t happen.

Foster really was there in the African-American dance halls of The Five Points, for better or worse, and he remains an important part of the story. The music and melodies he heard there he made, WE made, part of American culture, for better or worse.

“Something for everyone”

“Before its scheduled March opening on Broadway, Paradise Square has a bit of revising to do. A very small bit,” Catey Sullivan wrote in the Chicago Sun-Times.

Can the plots of most plays do with a bit of tightening and polishing? Sure. Hell, this article may be tightened and polished by the editors before it runs in Irish America magazine.

But I hope most of the complications that make Paradise Square so compelling stay in the show.

Critics from privileged backgrounds who grew up as single children in the suburbs in ordered households with stay-at-home Moms who had time to tidy the houses and fold napkins before dinner may have trouble following all the complicated forces threatening this community.

But if you grew up in rough-and-tumble Irish or African-American homes with siblings, cousins, dancing, drinking and chaos, you’ll have no problem following Paradise Square.

I brought my wife, two of my sons and my impossible-to-please younger teen daughter to see Paradise Square and they were all blown away by it. The awesome singing and dancing alone might have been enough, but the storyline that is so inspiring and exasperating all at once seals the deal.

“I think Paradise Square has a little bit of something for everyone,” Stampley said. “The dancing and singing is incredible. You are going to get upset. You are going to cry.”♦

Got to see it,

Saw the show on Broadway in mid-April and loved it. Amazing sets and choreography, boundless talent and energy made for a dazzling performance. Played to a nearly full house and a standing ovation. Bravo, indeed.

please do a tour around the country!