How a veteran of WWII spent his post-war life helping other vets.

Harry Donovan and two other sailors labored in darkness, setting smoke pots on the water to prepare for an island invasion the next morning. In daylight, billowing smoke would surround Allied ships and prevent Japanese pilots from locating and bombing them.

Their task completed, the men headed back to their assigned ship – only to discover that it had vanished, and so had the rest of the fleet. The invasion had been postponed.

Forgotten and stranded, the men bobbed about on the Pacific Ocean for four days. They couldn’t go ashore since the enemy occupied the island, but their small landing craft wouldn’t fare well if they ventured further out to sea. They ran out of food and water and prayed no enemy would spot them.

Donovan described this harrowing experience to fellow veterans at a meeting of the World War II – Korean War Roundtable in Fairlawn, Ohio in April 2013.

“I said, ‘God, if I ever get back to food and water, I’ll never eat any food without first thanking you,’” Donovan told them.

Near the end of the fourth day, the sailors’ luck improved when they sighted an American LST (Landing Ship, Tank). Not only did the captain welcome them aboard for a meal and a shower, but he invited them to spend the night there. Donovan thought they should remain in their assigned territory and he didn’t want to leave his own boat unmanned. He and his crewmates went back to it, but thanked the captain and promised to return for breakfast. Before they could do that, however, a Japanese plane attacked the LST and killed most of its crew. By luck, Donovan had been spared. He rejoined his regular ship soon after.

Youthful lessons

The family name was “O’Donovan” when Donovan’s grandfather passed through Ellis Island, fresh from County Cork. Harry Donovan grew up in Akron, Ohio where he took his first job at age 11, working in a grocery store. Although the family struggled during the Great Depression, his mother fostered Donovan’s lifelong generosity when she insisted he give ten percent of his wages to his church. Donovan later recalled her frequent admonition, “Help someone across the bridge, and you’re both across.”

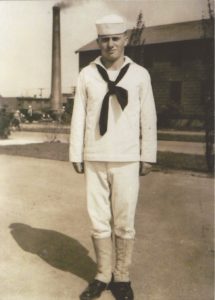

Within days of his 17th birthday in February 1944, Donovan dropped out of high school and persuaded his mother to sign permission for him to join the Navy. He attended boot camp and headed for the Pacific theater, where he served aboard the USS Arthur Middleton, an attack transport then operated by the U.S. Coast Guard, and also on the Navy’s USS Leon. A Higgins boat coxswain (driver), he ferried soldiers or Marines ashore during island invasions. For the rest of his life, Donovan claimed the Navy had “made a man” of him.

In a candid 2013 speech to fellow vets, Donovan related his most painful wartime memory. At age 85, he was unsure about the island where it occurred, but he remembered taking 32 men ashore, and then returning to the ship to pick up a second group of 32.

“And when I got back there [to shore], oh, my God! All of these bodies were there, floating!”

Horrified, he realized the long “dug-in” Japanese had ambushed the Americans as they left the water.

Donovan returned to the ship, reported what he had witnessed and refused to deliver a third group to almost certain death on shore.

His furious captain gave the 17-year old sailor a choice: do his job or land in the brig. Donovan opted for the brig, where he apprehensively awaited court martial for the rest of that day and throughout a sleepless night.

Instead, the matter ended at daybreak when his officer summoned the teenager and said, “You might have been right. Go to work.”

Donovan knew his brother was stationed on American-occupied Guadalcanal. He requested permission to go ashore when his ship made a brief stop there. Although the captain doubted that Donovan could locate his sibling among the mass of soldiers, he agreed to let him try. Donovan took a Higgins boat ashore, but once there, he hesitated, unsure of where to go next. Seeing a group of soldiers in the distance, he decided to approach them in hopes that they would know the whereabouts of his brother’s division. He interrupted their conversion, tapping a man on the shoulder to ask. He was astounded when the GI turned to face him.

“It was my brother Bill!” Donovan exclaimed.

He visited Bill’s tent and met his beer-thieving pet monkey, an episode that still amused Donovan decades later.

The young sailor’s good luck didn’t get him through the war unscathed. During one battle, an explosion tossed him against his ship’s bulkhead and knocked him unconscious. He awoke in the sick bay much later with an excruciating back injury. Bristling at his prolonged recuperation, he begged for permission to help the cooks. Working in the galley proved to be the perfect therapy. For the rest of his life, he loved to prepare meals for family and friends.

When General Douglas MacArthur fulfilled his “I shall return” promise to the Philippines on October 20, 1944, Donovan piloted the Higgins boat that took the famous man ashore at Leyte. The historic event did not make much of an impression on the teenager, however. It wasn’t until 2011 that someone showed him the iconic photo of MacArthur wading ashore and Donovan realized he probably was the short man trailing the general in knee-deep water.

“I just happened to be there at the right moment,” Donovan said. “When we went ashore, a band was playing. And I can still see the mayor – he’s got on a white shirt and a white hat.”

The happy moment was fleeting – within hours Donovan witnessed fighting elsewhere.

Sharing time and treasure

Donovan left the Navy in 1946. After meeting college admission requirements, he used the GI Bill of Rights to attend the University of Akron, washing cars to make ends meet while he earned a degree in accounting. He married his sweetheart, Mabel, in 1947 and they raised three children. Their union lasted until Mabel’s death 56 years later.

Donovan’s back injury plagued him during those early years and he sought treatment at Crile General Hospital, a military medical center in Parma, Ohio. One December another patient confided that he would not see his family at Christmas because his West Virginia home was too distant. Appalled, Donovan asked the hospital director to release – just for the holidays – any ambulatory man who lived too far away for a day trip. The administrator explained there was no budget for travel costs, and he suggested that Donovan cover them out of his own pocket. Donovan agreed to this arrangement.

In January, he received a bill for a $4,000, a staggering sum at that time.

“But I will tell you that was probably one of the better Christmases I spent in my life,” Donovan said years later, choking up. “Knowing I had done that.”

Meanwhile, his career flourished. He became a certified public accountant and eventually opened his own business. Besides helping clients to manage their expenses and their assets, he encouraged them to give 10% of their income to a church or charity. He assured them a tangible return on this kindness. Donovan followed his own advice, and he prospered, retiring at age 40.

His widow, Fran, whom he married after Mabel died, described Donovan as a successful investor.

“He had a knack for being in the right place at the right time,” Fran Donovan said, citing his involvement in the development of Marco Island after he’d retired to Florida.

Because idleness didn’t suit Donovan, his first retirement lasted only a few years. Thereafter, he divided his time between Florida and Ohio, where he started a new accounting firm. He delegated tax work to employees, while he consulted clients on business management. Over time, the boards of 42 companies and corporations sought Donovan’s advice, and he addressed business groups around the country. He served as a presidential economic advisor during Richard Nixon’s administration.

All the while, Donovan continued promoting the practice of tithing. For Guideposts Magazine he wrote a pamphlet on the subject, “Need More? Give More!” National and local nonprofits benefitted from his financial contributions, but he also gave them countless volunteer hours, serving on the boards of the Hospice & Palliative Care of the Visiting Nurse Association and other charities. For decades he volunteered at Akron’s Opportunity Parish Ecumenical Ministry (OPEN-M). The organization, which offers meals, medical care and employment counseling to the disadvantaged, originally operated out of a little house. When Donovan served hot meals there, he recognized the critical need for a larger space. The building seated too few hungry people at a time, while many more waited outside in all weather for their turn. Ever practical, Donovan began to buy adjacent lots at his own expense whenever they came on the market. After several years, he had acquired the necessary land, and he next assisted in the successful fundraising campaign for a new building.

Today OPEN-M annually assists around 40,000 persons. In October of 2021, it added the Harry and Fran Donovan Dental Clinic to its services.

Helping other veterans

A “life” member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, Donovan established scholarships for veterans’ children and “Donovan’s Kids” to give camp experiences to disabled children and to veterans’ families. For years, the former sailor served on the board of Honor Flight of Akron/Canton, which flies aging veterans to Washington, DC to see the national WWII, Korean War and Vietnam War Memorials. He donated to his county’s “Stand Down” where he also helped distribute clothing, toiletries and other essentials to homeless and at risk veterans. Aware of this growing problem, Donovan became a major contributor to the construction of Valor Home, veteran-specific transitional housing in Akron, Ohio. When it opened in 2013, he declined the honor of naming the facility for him. Instead, he asked that the tribute go to his son, Harry Donovan, Jr., an Army veteran who was wounded multiple times in Vietnam.

Wanting to help more than the 30 men Valor Home can accommodate while they rebuild their lives, Donovan created the Harry and Fran Donovan Fund for Veteran Care. Since 2014, it has provided treatment for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) through Summa Health, an Ohio-based hospital system.

Harry Donovan died on February 8, 2018 from complications from injuries he’d suffered in a fall. He was 90 years old.

Donovan did not live to see the opening of a pet project, Cleveland’s Fisher House, the following year. Perhaps remembering his long ago efforts to reunite veterans with their families at Christmas, he supported this facility that provides cost-free, home-like lodgings to families from around the country when their husbands, wives, sons and daughters are patients at nearby Louis Stokes Veterans Administration Medical Center.

And although Donovan had funded “They Served, Too,” a documentary about female veterans, he never saw it. “They Served, Too” aired on Public Broadcasting System stations after his death.

His largesse remains apparent today at the National WWII Museum in New Orleans. A longtime contributor, he sponsored the MacArthur Returns exhibit in its Road to Tokyo gallery.

By the time he died, Donovan was channeling half of his income to veteran-related nonprofits.

“God has been so good to me,” he often said. “The best way to show my gratitude is to give back to my fellow veterans.”♦

Leave a Reply