Elizabeth Thompson is one of the most intriguing Irish characters who traveled alongside George Washington during and after the Revolutionary War.

She was the elderly head of his household and oversaw about two dozen staff for five years during the war, constantly moving with the commander-in-chief as he frequently changed residences to keep the British off his trail.

Little is known about her personally. Thompson was her married name and it seems very likely she was of the Presbyterian faith, a fact learned through her will where she left her possessions to a Presbyterian church in New York.

Incredibly, she was 72 when she took the job in July 1776. It was a post that involved a very heavy workload, not least attending to the general’s comfort when he moved camp as he did incessantly. By the end of the war, Washington had moved 90 times in order to keep the British guessing as to his whereabouts.

Washington probably saw more of her than anyone other than close family. The two got along famously.

It is hard not to speculate that the warm, down-to-earth Thompson was some kind of replacement for Washington for the flinty mother who had raised him but who, by all accounts, shunned him and failed to recognize his achievements.

Thompson was hired after Mary Smith, her predecessor as a housekeeper, was revealed as a British spy by an anonymous letter. Smith subsequently fled to England. She was thought to be part of the Governor William Tryron plot, the loyalist leader who sought to have Washington killed.

Washington was quite distraught at that discovery and immediately sought a replacement. He wrote to General Clinton in New York for help:

New York, 28th June 1776.

Sir,

Having occasion to part with my Housekeeper, a Mrs.Thompson somewhere in your Neighbourhood, is recommended to me as a fit person to supply her place. I, therefore, give you the trouble of forwarding the Inclosed Letter to her, & beg of you to hasten her to this place or an answer, as I am entirely destitute, & put to much inconvenience for want of discharge the duties of this Office.

I am Sir Your Most Obt Servt

Though then aged 72, Thompson came immediately. Soon she was in charge of all kitchen staff and ensuring the general’s comfort and tastes were met. In 1777 alone, he slept in 24 different houses.

As historian Nancy K. Loane wrote in the Journal of the American Revolution: “Elizabeth Thompson was a key figure overseeing the mobile military household.” For five years Thompson traipsed up and down the East Coast preparing scores of different locations for the often-exhausted commander of the Continental Army.

At times of such great stress, one can only imagine how important it was for Washington to see Thompson’s familiar face in every different halting place.

It is clear from the tone of their letters in later years that a genuine fondness existed. Washington even took the unprecedented step after the war of offering Thompson a home at Mount Vernon to live out the remainder of her days. However, Thompson, then in her 80s, had too many infirmities to travel.

Her job bore huge responsibilities. Loane explains: “To help make these transitions go smoothly, the general traveled with a ‘military family’ that included his aides-de-camp and personal servants as well as two cooks, a laundress, and a housekeeper. Mrs. Elizabeth Thompson, a personable Irish woman, took on the position of Washington’s housekeeper for most of the American Revolution.”

It was certainly an onerous position, especially for a woman so advanced in age. There were a total of 25 employees, led by Isaac the cook, and her job was to ensure dinner was served at 3:00 pm each day as Washington avoided eating late. Then there were the laundresses, the housework, ensuring cutlery was cleaned, and the job of making sure every guest room was ready for its occupant. Thompson always slept in the same house as Washington in order to be available at any time.

Most importantly, Elizabeth was in charge of packing up camp at a moment’s notice and moving to the next secret location. One can only imagine the strength of character needed for such constant change. She was also available to answer any domestic questions from Martha Washington.

What was George Washington like in person? Hannah Till, a freed slave who worked alongside Elizabeth Thompson as a cook, was interviewed about him in 1824. She was then 102 years old. Historian John F. Watson said she had good memories of her employer: “She said he was very positive in requiring compliance with his orders, but was a moderate and indulgent master. He was sometimes familiar among his equals and guests and would indulge in a moderate laugh. He always had his lady with him in the winter campaigns, and on such occasions, was pleased when freed from mixed company and to be alone in his family.”

Another look at the private George Washington came from Army wife Martha Bland who knew General and Mrs. Washington well, as her husband, Col. Theodorick Bland, was a friend of the commander in chief. She often went on horseback rides with Washington and his wife Martha.

Mrs. Bland found that the commander displayed an “ability, politeness, and attention” that she found charming, saying that occasionally, Washington “throws off the hero, and takes on the chatty, agreeable companion – he can be downright impudent sometimes.”

This was the private man who would capsize the world. Elizabeth Thompson would know him as well as anyone bar his family.

We know little about where Elizabeth Thompson hailed from, other than the fact that she was Irish.

She was clearly well-liked. Dr. James Thacher, a surgeon for the Continental Army, stated that Mrs. Thompson was “a very worthy Irish woman.” Martha Washington, a strict mistress, liked Thompson so much she sought to hire her for Mount Vernon after the war. At that stage, Thompson was 77, a great age for the time, but obviously holding her years well.

Thompson had been briefly let go by Washington soon after arriving in the army camp because the army was moving to winter quarters. This was before she had struck up a close connection with the commander, but Washington quickly learned to his chagrin that Martha, his wife, very much wanted her back.

On May 1, 1777, General Washington wrote to an aide “Mrs. Washington wishes I had mentioned my intentions of parting with the old Woman before her, she is much in want of a Housekeeper.” Elizabeth was soon back permanently.

She was illiterate, so we never get to hear her own voice, but we do have her letters to Washington as dictated by her. The demanding job of housekeeper for General Washington is clear, as well as the affection she felt for him.

The following letter is dated October 10, 1783, and Elizabeth is responding to a request from Washington to lay out the wages and remuneration she had gotten.

“When I had the favour of seeing your Excellency at Princeton you desired that I should make an Account for my Services in your Family to be laid before the Financier.

I came into Your Excellency’s Service as Housekeeper in the month of June 1776 with a Zealous Heart to do the best in my Power. Although my Abilities had not the Strength of my Inclinations Your goodness was pleased to approve and bear with me until December 1781 when Age made it necessary for me to retire.

Your Bounty and goodness in that time bestowed upon me the sum of £179.6.8 which makes it impossible for me to render an Account: my Service was never equal to what your Benevolence has thus rated them.

And being now in my Eightieth Year should I ever want, which I hope will not be the Case, I will look up to Your Excellency for Assistance where I am sure I will not be disappointed.

And that the Father of Mercies may pour on you his Choicest Blessings shall ever be the Prayer of

Your Excellency’s

Old Devoted Servant

Elizabeth Thompson

Washington acted promptly, not only helping acquire a war pension for Elizabeth but, as she wrote to Congress, “the General who was always kind to me, and whose countenance was a comfort to me when our affairs were at the worst” had invited her to spend her final days “in his own house” — Mount Vernon. But at eighty-one, Mrs. Thompson had a “heap of infirmities” that made travel impossible

She died in 1788 in New York. She bequeathed her silver teapot and cream pot with six teaspoons and tea tongues to help fund a new school for poor Presbyterian children, many of them black, in New York. The school opened in 1789. Her role in running George Washington’s household placed her at the beating heart of the American Revolution. It was an extraordinary place to be for a former Irish immigrant and she gained true friendship with Washington and his wife in a way that few could.

Years later, Washington was still asking about her in his letters to friends in New York. It is clear she impacted him greatly and offered safe refuge and rest nightly from the storms of the Revolution. ♦

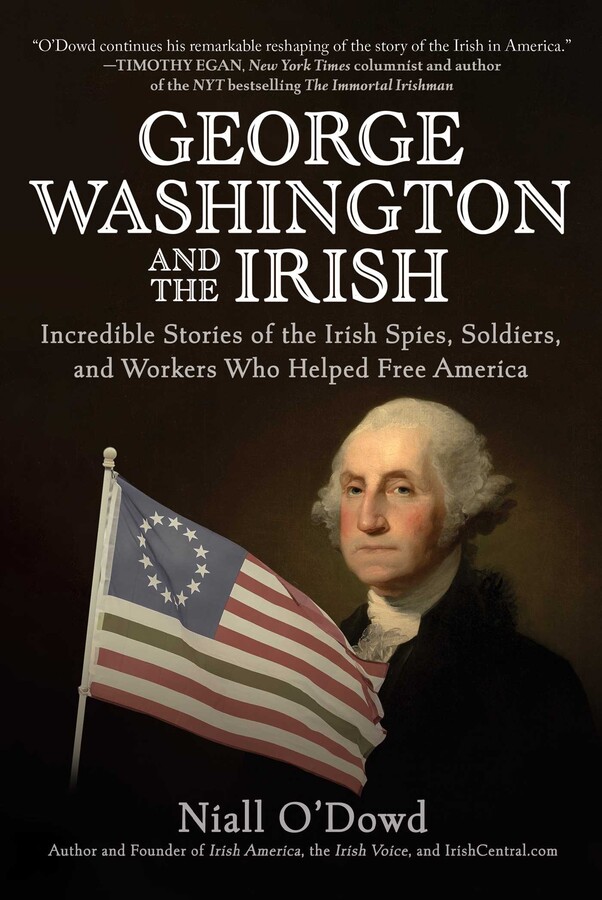

New York Times columnist Tim Egan reviews George Washington and the Irish.

George Washington and the Irish: Incredible Stories of the Irish Spies, Soldiers, and Workers Who Helped Free America is available for purchase from Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

What a terrific surprise to find this chapter from Niall O’Dowd’s new book — and written by Nancy Loane, no less.

Nancy’s knowledge of the Valley Forge winter and the long unsung role of women in the American Revolution is second to none, and her own book, Following the Drum, is as engaging a read as it is an important one.,

Thanks Patricia, for providing us another great read for our Saturday mornings!

I loved this story about the Irish woman who provided so well for Washington, There are so many unsung heroes and heroines in history!

This story would make a great novel and film.