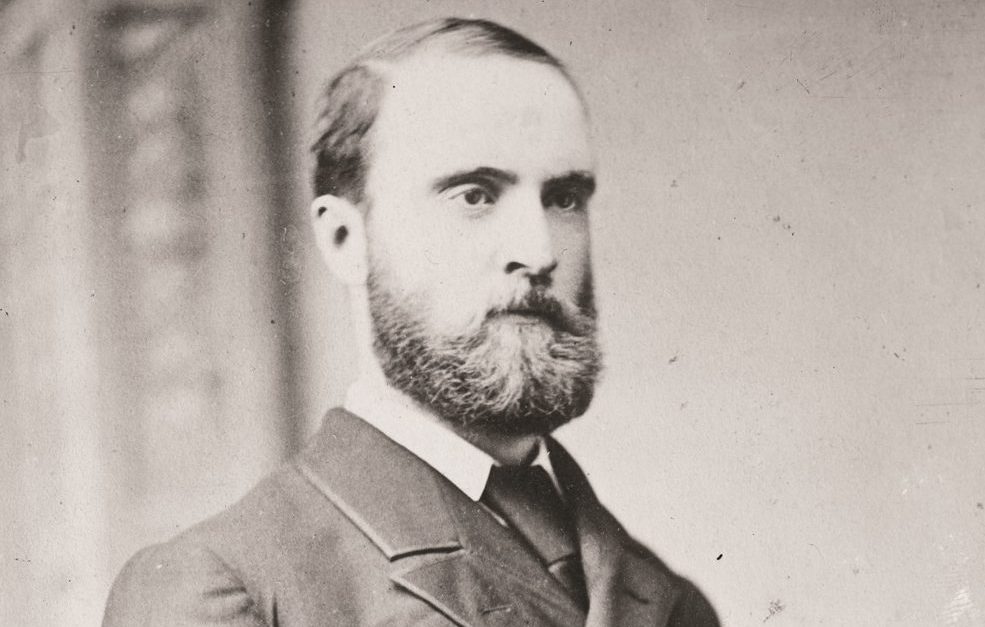

On Monday, February 2, 1880, Charles Stewart Parnell addressed the American Congress. He was only the fourth international politician to be accorded this honor and the first Irish man. During his 32-minute-long speech, he laid out a blue-print for the end of the much-hated landlord system in Ireland. He also linked it to recurring famines in Ireland. The success of Parnell’s North American tour led to him being referred to as “the uncrowned king of Ireland.” Only ten years later, however, a public divorce scandal would lead to Parnell’s public, and meteoric, fall from grace and to a major split in the Home Rule Party. The following year, Parnell was dead. He was 45 years old.

Parnell was born in County Wicklow in June 1846 – a year associated with blight and starvation, and the onset of mass evictions, emigration and death. Born into a land-owning family that was part of the Protestant ascendancy, he could have chosen a life of privilege. Instead, the family, led by his indomitable American-born mother, Delia, and his intrepid sisters, Anna, Fanny and Theodosia, devoted large parts of their lives to fighting for Irish independence and an end to land inequality.

Parnell’s father’s family were wealthy Anglican landowners, while his mother, Delia, had been born in Boston in 1816 and was the grand-daughter of Admiral Charles Stewart, the naval hero of the 1812 War between the United States and Britain. As part of upper-class Irish society, Parnell’s six sisters were presented at court, the first step to finding a husband. Fanny and Anna, however, turned their backs on marriage and motherhood, instead forging a distinctive place in nationalist and feminist activities that paved the way for the next generation of militant women activists.

Nationalist politics, in the form of Fenianism, was brought into the Parnell household by Charles’s younger sister Fanny. According to Thomas Clarke Luby, founder of the Irish People newspaper, Fanny first published in the paper in 1864, when aged only 15. To disguise her gender and her youth, she used the pen-name Aleria. Thus, it was probably Fanny who first brought her brother into contact with radical nationalist ideas. In 1865, three of Aleria’s poems were cited by the British authorities in Dublin Castle when convicting a number of Fenian leaders of sedition.

From an early age, both Fanny and Anna rejected the traditional path of marriage, children and domesticity, which was expected of women of their social position. Fanny continued to write and to compose poetry, but increasingly using her own name. Her poetry appeared in the nationalist press in Ireland and North America, making her a household name whose fame exceeded that of her brother. Later, she would use these skills to good effect – not only helping Charles manage his successful career but writing a number of his most important speeches.

In 1875, Charles was elected to the Westminster Parliament as Home Rule MP for County Meath. Initially, he said little, but he came to the attention of Irish nationalists – and no doubt the British government – when, in May 1876, he spoke in defense of Fenian prisoners, including Michael Davitt and the Manchester Martyrs. Fanny and Anna attended, watching the debates from the Ladies’ Gallery, which they renamed the “Ladies’ Cage.”

Charles’ contribution to the parliamentary debates consolidated his position as a leading figure in the Home Rule Party, despite his youth. In August 1879, the Land League was formed in Castlebar, dedicated to helping poor tenant farmers resist high rents and brutal evictions. While Michael Davitt was the real moving spirit behind the League, Charles was appointed its President in October, thus combining the power of parliamentary politics with the populist movement for land reform. It affirmed his position as the most important person in Irish nationalism. He was 33 years old.

At the end of 1879, Charles sailed to New York to undertake a lecture tour of North America. There, he was met by his mother and his sisters Fanny, Anna and Theodosia. Delia, Fanny and Theodosia now lived in Bordentown, New Jersey, while Anna had traveled over from Ireland to help prepare for Charles’ tour. Together, the Parnell women dealt with the logistics of their brother’s visit: raising money, liaising with the press and Irish American supporters, and – in the case of Fanny – writing his speeches.

The tour coincided with the reappearance of famine throughout the west of Ireland. From her home in America, Fanny used her celebrity status on both sides of the Atlantic to intervene in a practical way. In September 1879, she published an appeal to Irish Americans to raise subscriptions for people in Ireland, asking: “Will not the Irish here, who can afford it, give something from their conveniences to help our countrymen in their terrible need? I know that I do not appeal to hard hearts or closed hands.”

She and her sisters also made several donations to famine relief and they viewed Charles’ visit as an opportunity to raise more funds and to highlight that recurring hunger was one of the consequences of the existing land tenure system in Ireland.

Charles arrived in New York at the beginning of 1880, on the first stage of an extensive tour of North America. Encouraged by his sisters, one of his first actions was to establish an Irish Land League Famine Relief Fund, partly to answer criticisms accusing him of indifference to the situation. On the day of his arrival, he made a speech in which he stated, “In 1845, the Queen of England was the only sovereign who gave nothing out of her private purse to the starving Irish. The Czar of Russia gave, as did the Sultan of Turkey, but Queen Victoria sent nothing.” Although not historically accurate (Victoria donated £2,000), Charles was helping to create a powerful narrative about the monarch’s indifference to Irish hunger and suffering, which would prove to be enduring. Tellingly and typically, Charles left it to his sisters to manage the Relief Fund. They hired an office in New York to act as headquarters. One of their novel ideas was to leave boxes in post offices and other central establishments throughout America that could accept donations.

Two days after his arrival, Charles spoke in Madison Square Garden. An estimated 8,000 attended, despite a charge of 50 cents. In Irish newspapers, Fanny was also billed as a speaker, but American newspapers merely noted that “Mrs. Parnell and her three daughters” were present. Charles had been in America for only a few weeks when he was accorded the unusual honor of being invited to address a specially-convened evening session of Congress.

On the eve of Charles’ tour of America, Fanny had published a treatise entitled, “The Hovels of Ireland,” its purpose being “to create and foster sympathy with Ireland amongst Americans.” Proceeds from the sales were to go to the Land League Fund. In it, Fanny identified two key injustices: first, the wrong of English rule as it exists in Ireland; secondly, the wrong of landlord rule as it exists in Ireland. It was an unequivocal attack on the class into which she had been born. Many of the ideas presented in “Hovels” would be at the heart of Charles’ speech in Congress about how to end British rule in Ireland and bring about a social revolution in land ownership.

Charles arrived in Washington by train on February 2. He was accompanied by his mother and Theodosia, and his Irish colleague, John B. Dillon. They were greeted by a large crowd who accompanied them to the prestigious Willard hotel. When addressing the welcome committee, Charles referred to the situation in Ireland, telling them, “The present famine is artificial. It was deliberately created to prevent the restoration of the rights of the people and to keep down the peasantry.” The same evening, he addressed Congress. Despite the cold and snow, large crowds had queued for hours for a place in the public gallery. Many were women and, as was the case with the British parliament, there were separate galleries for women and their companions. In contrast to the crowded galleries, only about 100 of the 293 Representatives were present. Charles spoke for just over half an hour. After he finished, he met some of the Representatives before returning to his hotel for a private reception. In the after-dinner speeches, the famine in Ireland, where up to one million people were being kept alive by international relief, was frequently referred to. Newspaper coverage on both sides of the Atlantic was extensive but polarized. According to the Irish Times, Charles spoke with “coolness and effect … and made a most favorable impression by his self-possession and clearness of utterance.” Not all reports were so favorable. The Glasgow Herald described the invitation as proof of the “eccentricity” of American politics, adding that the House of Representatives should have shown better judgment than giving a platform to “a shallow and insolent braggart.”.

Charles returned to the United Kingdom in early March, earlier than anticipated, to contest an unexpected General Election. At this stage, he had lectured in 62 cities in 60 days and the success of his tour led to his being referred to as “the uncrowned king of Ireland,” a title that had also been used to describe Daniel O’Connell.

Although Charles had left America, his legacy included both a Famine Relief Fund and a Land League Organization Fund, the latter having already raised almost $25,000. On his departure from the country, the longshore men of New York gave him a check for $1,000 “for the relief of the suffering people of Ireland.” In addition to the financial support, his visit to the United States had given him a new-found transatlantic fame – a fame that was only paralleled by Fanny’s.

Even after Charles’ departure, support for the famine and land reform continued in America largely due to the energy and abilities of Delia and Fanny. Anna had also returned to Ireland and Theodosia married a British naval officer, Claude Paget, in August 1880, in Paris. However, over the summer famine donations did dry up, possibly due to the improved chances of a good harvest in 1880. Fanny continued to use her writing skills to keep attention on the need for land reform. In August 1880, what would become her most famous poem, “Hold the Harvest,” was published in the Boston Pilot. Its opening lines were critical of Irish men who preferred to starve rather than protest:

Now are you men or cattle then, you tillers of the soil?

Would you be free, or evermore in rich men’s service toil?

The shadow of the dial hangs dark that points the fatal hour

Now hold your own! Or, branded slaves, forever cringe and cower! …

For Michael Davitt, an admirer of Fanny’s writings, the poem represented “The Marseillaise of the Irish peasant,” an allusion to the anthem of the French revolutionaries in the 1790s. The British press was less impressed, alarmed at Fanny’s radicalism and her influence over her brother. According to one paper, “What Miss Parnell sings Mr. Parnell speaks.”

As “Hold the Harvest” was continuing both to delight and disturb people in Britain and Ireland, Fanny was developing a plan to establish a Ladies’ Land League in North America. Her justification was that the funds of the League were inadequate in the face of widespread evictions, and the male leaders were about to be arrested. Davitt later admitted that the idea of women forming their own association was not universally popular, “this suggestion was laughed at by all except Mr. Egan and myself, and vehemently opposed by Messrs. Parnell, Dillon and Brennan, who feared we would invite public ridicule in appearing to put women forward in places of danger.” Davitt was adamant, however, that when the men were imprisoned, “No better allies than women could be found.” Fanny and Davitt prevailed, leading a newspaper in County Kerry to predict: “The three L’s will occupy as prominent a position in the present agitation as did the three F’s.” At meetings of male Land Leaguers in Ireland, cheers were called for Fanny and suggestions were made that a similar organization should be formed in Ireland. Shortly afterwards, in January 1881, Anna announced that a Ladies’ Land League was to be established in Ireland. By May, there were 321 branches in the country.

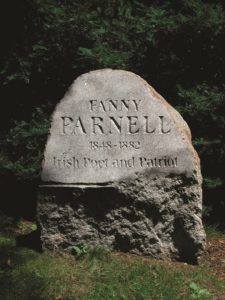

On July 20, 1882, Fanny died at her home in Bordentown, possibly of a heart attack. She was 34 years old. Earlier that day, she had met with John Dillon and Willie Redmond, two leading Irish nationalists. Charles was heart-broken at the news, yet he denied Fanny’s wish that her body be buried in Ireland. Instead, she was buried in an unmarked grave in Boston. At the time of her death, Charles was negotiating with the British government about a political amnesty, and he had already decided to disband both the men’s and the Ladies’ Land Leagues. For this act of betrayal, Anna never forgave, or spoke to, her brother again. It is probable that Fanny would have been similarly outraged.

Despite having lost the support of his sisters, Charles continued to be the most influential figure in Irish politics, even persuading the British Prime Minister, William Gladstone, to introduce a Home Rule bill in 1886. The following year, Charles was successful in proving that the London Times had lied in accusing him of being complicit in the Phoenix Park murders of 1882. Amongst his many supporters was fellow Irishman, Oscar Wilde. At this point, Charles Stewart Parnell appeared unstoppable in his political aims and ambitions.

In December 1889, William O’Shea, formerly a loyal supporter and friend of Charles, filed for divorce from his wife Katherine on the grounds of her adultery. Charles and Katherine had been in a relationship for many years and had three children together. It was an open secret until O’Shea filed for divorce, and then it could not be ignored. The scandal led to a bitter split in the Home Rule Party, with Charles being replaced as leader. Even formerly close allies, including Dillon, shunned him.

Charles died in Brighton on October 6, 1891. Ireland had lost one of its most skilled political leaders. Moreover, he was a man who had the ear of British politicians and who had advocated for an ending to the very class of Protestant landlords into which he had been born. Charles’ invitation to speak in Congress was one of the highlights of his multiple achievements, proving to the British Establishment that support for Irish Home Rule and land reform was international and to be taken seriously. Most importantly, the actions of the Parnell family helped to lay the foundation for a social revolution in land ownership in Ireland. It was this revolution that would bring an end to the country’s centuries of deadly famines.

To read Charles Stewart Parnell’s full speech to Congress click here.

Life in Ireland in the 1800s

After years of being ravaged by Famine, countless Irish tenant farmers across Ireland were evicted fron their home by English landlords. 1988: The eviction of tenants for non-payment of rent on the Captain Hector Vandeleur estate in Co. Clare. The Michael Cleary family (1st and 2nd photos). The Pat Spellecy family (3rd photo). The McGrath family (4th photo).

Photographs from the John Sexton collection.♦

An excellent article for educational purposes. However, I thought the “Land League” was formed in Irishtown near Ballindine in Mayo, not Castlebar.