For someone whose New York Times obituary described him as the 19th century’s “most conspicuous” English-language dramatist, Dion Boucicault all but vanished in subsequent eras. During his career, though, his plays were sometimes wildly successful, and he also made an impact in the domain of copyright laws for dramatists. At the same time, he was liable to make unwise business decisions and erratic choices in his personal life.

The complexities in Boucicault’s story begin at his birth in Dublin: Uncertainty has persisted regarding whether he was born on Dec. 26, 1820 or Dec. 26, 1822. Also uncertain is his paternity, though Dionysius Lardner, an astronomy professor at University College London, typically gets the credit (he also provided longstanding financial support).

Boucicault’s mother, Anne Darley, belonged to an important Dublin family and was the brother of the poet-mathematician George Darley. She was less-than-happily married to a French Huguenot man named Boursiquot (from which the Boucicault surname derives).

Dion Boucicault received his education in both Dublin and London, and he proceeded to serve as an apprentice civil engineer. Likely finding this position uncongenial to his dramatic temperament, however, he soon abandoned it to embark on a career in the theater.

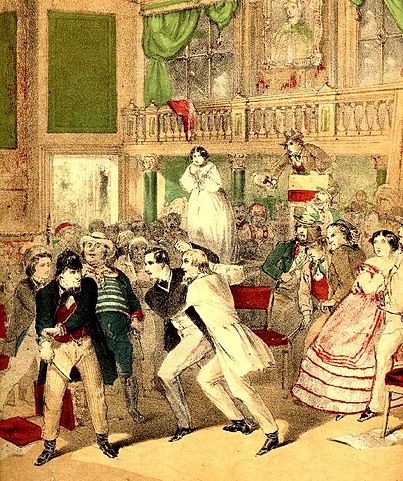

When he was still only about age 20, Boucicault found enormous success as a playwright with “London Assurance,” a comedy in five acts premiering in 1841. Newfound popularity made him a marked man, though, and soon enough London critics were condemning him for borrowing too heavily from other writers’ dramas. Boucicault himself made no secret of the fact that his tendency to adapt the work of others often exceeded his tendency to create original work.

Whichever method he chose, Boucicault was mightily prolific. Britannica.com credits him with about 150 plays, and other sources place a higher number yet. He also acquired a widespread acting reputation after making his debut as lead actor with “The Vampire.” The play itself, which premiered in 1852, was regarded as too ghastly to have much literary merit, but Boucicault’s onstage performance brought him much praise.

Many spectators would come to the opinion that Boucicault’s acting talents were best suited to portraying hard-luck characters, even more so if those characters were Irish. He even acquired the nickname “Little Man Dion” for his excellence in playing roles on the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder.

In 1853, the ‘Little Man’ sailed for the U.S., where his plays and reputation had already preceded him and where he would live for much of the rest of his life. Aside from writing prolifically in the U.S., he played a leading role in securing America’s first copyright law (issued in 1856) for the works of playwrights.

Among Boucicault’s most important U.S. works was “The Octoroon,” an antebellum melodrama involving a Louisiana woman who, being of one-eighth African descent, is therefore legally prohibited from marrying the white man who loves her. As related in a 1975 issue of the Educational Theatre Journal, renditions of the “The Octoroon” tended to end happily on British stages but ended with suicide and tragedy on U.S. stages in order to avoid upsetting prevailing viewpoints by depicting a successful mixed-race relationship.

Though Boucicault eventually became a U.S. citizen, he continued to take interest in the pressing issues of his native land and remained a “strong advocate of Irish home rule,” according to the 1901 Dictionary of National Biography.

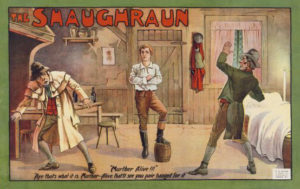

His Irish-themed plays, such as “The Shaughraun” and “The Colleen Bawn,” were almost astounding commercial triumphs across both the U.K. and the U.S. Boucicault reaped huge profits – and then basically lost them all, whether through his mismanagement of several theaters or his hefty alimony payments to the wife he abandoned.

Boucicault married three times. His first wife, Anne Guiot, reportedly died in 1845, the same year they married. His second marriage, to the actress Agnes Robertson in 1853, lasted more than three decades and produced six children (three of whom would become heavily involved with the theater). This union, however, ended under scandal unmatched by most any melodrama: While touring Australia, Boucicault, then well into his 60s, grew enamored with the 20-year-old actress Josephine Louis Thorndyke, and soon entered into a bigamous matrimony.

Surely he knew of the unflattering international headlines that awaited him and his new beloved, along with the embarrassing fallout for his longtime wife and six children. Whatever these factors amounted to inside his mind and heart, they did not prove a sufficient deterrent.

On Sept. 18, 1890, Boucicault – who was either age 67 or 69, depending on the version of his birth date – died in his apartment on 108 W. 55th Street in Manhattan. The playwright, who had battled frail health for years, was buried at Mount Hope Cemetery in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York.

Under the slightly melodramatic title “Dion Boucicault Dead: Pneumonia suddenly ends a wonderful career,” the New York Times ran his obituary, which mentioned how the playwright had recently sent a “sharp letter” to several newspapers in response to their criticism of “A Poor Relation,” his final play to appear during his lifetime.

This obituary for the “gifted, energetic, and brilliant Irishman” was at times akin to hagiography, but it also acknowledged that Boucicault “wrote many bad plays,” “helped himself to material wherever he found it,” and “was not always careful to give credit” to the other dramatists whose works he “adapted.”

Though his notoriety largely plummeted after his death, Boucicault remained of interest to some biographers, including a few who became rather inventive with the facts. In a New York Times letter to the editor (Dec. 13, 1916) Boucicault’s widow, Josephine Thorndike Boucicault, criticized a newly-released biography for incorrectly saying the once-famous playwright did not even have a gravestone.

Now more than a century later, we have a positive development: Dion Boucicault will return to the stage, courtesy of director Charlotte Moore’s adaptation of his 1857 play “The Streets of New York.” This drama, also known as “The Poor of New York,” will show from Dec. 4, 2021, to Jan. 30, 2022, at the Irish Repertory Theatre on 132 West 22nd Street in New York.

See the details about The Streets of New York now playing through January 30, 2022 at the Irish Repertory Theatre. ♦

Leave a Reply