In just a few weeks, Ireland – and the world – will mark the 50th anniversary of “Bloody Sunday.”

That was the gruesome, January 1972 day when British soldiers opened fire on civil rights marchers in Derry, killing over a dozen, and sending the Northern Ireland Troubles into a violent new phase.

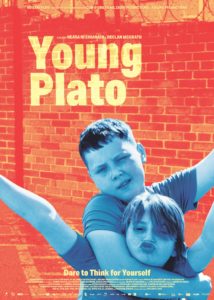

Soilsiú Films)

All those bullets and bombs have made it difficult to tell more intimate stories about life in Northern Ireland.

Two new movies do just that. Yes, The Troubles loom large over both Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast and the powerful new documentary Young Plato.

Yet both films also offer a more distinctive and nuanced view of Northern Irish life, which we don’t always get to see.

After directing global blockbusters like Thor, Cinderella and Murder on the Orient Express, Branagh returns to his Irish roots with this autobiographical black-and-white 1960s drama, starring Ciarán Hinds, Catríona Balfe, Jamie Dornan and Judi Dench.

The film, which Branagh wrote and directed, opened November 12, and is already being discussed as “a leading contender for Oscar glory,” as The New York Times put it.

Just as powerful, though, is a new documentary called Young Plato, which is available this week, and explores 21st Century life in the North.

Young Plato is being screened as part of the DOC NYC festival.

Director Neasa Ní Chianáin and producer David Rane will be in New York City, discussing the film after two screenings, on November 14 and 15.

Young Plato revolves around the daunting tasks faced by Kevin McArevey, headmaster at a grade school in Belfast’s Ardoyne section. The soaring rhetoric of historic and political struggle has been replaced by a generational cycle of poverty and drugs, crime and gun violence.

McArevey moves from passionate and caring, to stern or scholarly – frankly, whatever the kids or their parents need at any given moment.

Indeed, this is one of his top priorities – getting parents to understand what their young children are going through.

“Shock, horror!” he says at one point to a packed auditorium of adults.

“You’re going to have to talk with your child.”

McArevey also attempts to instill in his students the lessons of ancient philosophy – to get them thinking critically about the world around them, so as to begin healing the wounds many of them do not even know they have.

All the while, McArevey never stops belting out songs by Elvis Presley. You kind of just have to see that.

Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast, meanwhile, gives us a sense of the world that produced McArevey’s students.

In some ways, this is a simple, joyous, coming-of-age family drama.

Looming just over the horizon, however, is a combustible combination of rage, history and religion that may or may not send this Protestant family away from Belfast.

Not unlike the students in Young Plato, Kenneth Branagh – for all his success – struggles to explain the effects of growing up amidst such chaos and disorder.

“I hesitate to use the word (trauma) in the sense that this little story exists in a place among groups of people who had many, many more traumatic experiences,” Branagh told The New York Times Magazine last week.

“This was never spoken about partly because a cardinal sin for my parents was to be suggesting that anything you’d been through was worthy of categorizing in such a way. There’s no question that being shaken by the events of that time from my very particular 8-year-old perspective was, yes, I suppose you’d have to call that traumatic. But another cardinal sin was to indulge in your suffering. And yet over the years I’ve thought one doesn’t have to be doing that to go back and try and understand that this was a difficult time, which plenty of other people might recognize as such. Not to elicit pity but to share with them recognition that might be insightful in some way.”

In other words, Branagh seems to have learned a lesson Kevin McArevey tries to instill in his students.

“It’s time to think for yourselves.”♦

Leave a Reply