The most misunderstood metropolis in the United States is New Orleans. Mention the city and the mind instantly provides Francophile associations. The French Quarter is its most famous neighborhood, France’s pre-Lenten Mardi Gras celebration is the biggest annual bash, and Fleurs de Lis flutter on the municipal flag.

Regardless of popular thinking, New Orleans could as easily be associated with Ireland, and the city’s banner might just as well bear a shamrock. The Irish Channel is an equally famous population enclave, and the yearly St. Patrick’s Day parade is one of the oldest and biggest in the nation.

True enough, New Orleans’ original roots are French. Explorer Robert de La Salle claimed the region for France in 1682 and christened it Louisiana to honor King Louis XIV. Another Frenchman, Bienville, founded a town on a crescent of swampland formed by the Mississippi River and called it after the Duke d’Orleans. The settlement’s roots did not take hold, however, until 1731, when an ingenious Irishman named Charles McCarthy engineered the levee system that to this day holds back the Mississippi’s floodwaters.

When Louis XV bequeathed France’s Louisiana holdings in 1762 to his cousin, Charles III of Spain, the French settlers staged a revolution. Don Alexandre O’Reilly, an Irish ex-pat from County Meath, was sent in to quell the insurrection, and another Irishman, a merchant named Oliver Pollock from Derry, landed the contract to feed the soldiers. Spain returned the Louisiana territory to France in 1800, and just three years later Napoleon sold the whole kit and caboodle to the United States.

Still rankling from the loss of its American colonies, England attempted to seize the newest piece of U.S. real estate during the War of 1812. Only too happy to confront their historic adversary, Irish immigrants helped vanquish the British at the Battle of New Orleans by joining forces with Andrew Jackson, the cunning frontiersman born of County Antrim parents, who became our seventh president.

Prior to 1820, Louisiana’s Irish immigrants were people of means. Some were bankers, merchants, educators, attorneys and publishers. Others owned large cotton plantations (think Tara, the O’Haras and Gone With the Wind), and New Orleans quickly became the South’s major cotton exporting port to Liverpool. During the Famine years, the tide of Irish emigration swelled to a flood, and those same cotton ships sailed back across the sea filled with people seeking fresh starts in America.

Accustomed to back-breaking work on the farms they had left behind, the newcomers’ strong hands built New Orleans’ canals, roads, railroads, and levees. The hours were long but the pay was abysmal and, despite the established Irish presence within the city’s social register, these cash poor immigrants were outcasts. Undaunted, they established their own community. East of Canal Street lay the French Quarter. West of Canal, an exclusively Irish community sprang up which is still known as the Irish Channel. Coveting 100 city blocks, its shops, pubs, dance halls, hotels, restaurants, churches, and schools were the center of Irish social life.

Ireland’s influence so permeated New Orleans that it even colors the way people talk. Guide books note it strange how the local accent resembles that of Brooklyn. Pointing to the city’s French roots and Deep South location, the books suggest it would seem more likely for the residents to speak with Parisian inflections or a southern drawl, and they completely ignore the effect an Irish tongue has on the English language. The `th’ sound is pronounced as it is written, a hard `t’ followed by a short expelled breath, making this t’his, that t’hat, these t’hese, and those t’hose. At the beginning of the 20th century, waves of Europeans poured into both cities and learned English from their Irish neighbors. The hard Irish `t’ then evolved into a soft `d’ producing words like dis, dat, deeze, and doze.

One of the things New Orleans is best known for is its food, and though at first glance it may seem that the Irish had little effect in this department, nothing could be further from the truth. Louisiana’s spicy Cajun boiled shrimp, crawfish, and crab are always served with a pile of spuds which natives call “Irish potatoes.” Even better known is the New Orleans Branch which became a local tradition thanks to an Irish American named Owen Edward Brennan.

Born in the Irish Channel district in 1910, the enterprising Brennan tried several occupations before becoming a restaurateur. He owned interests in a gas station and a drugstore, worked as a liquor salesman, and served as district manager for Schenley Whiskey, but it was a stint as manager for one of New Orleans’ oldest dining spots, The Court of Two Sisters, that set the stage for his success.

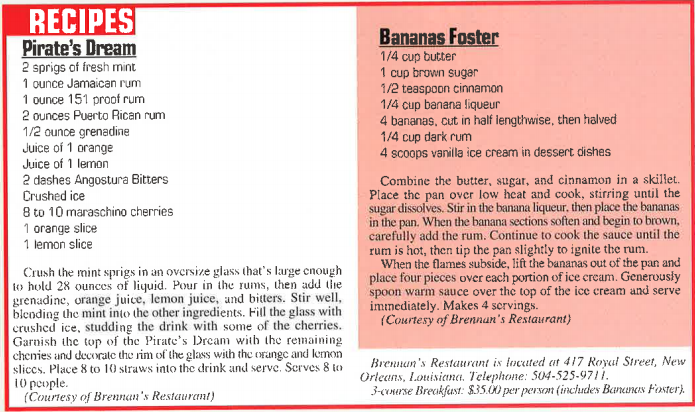

In September 1943, Brennan purchased the Old Absinthe House, a Bourbon Street landmark since 1798 when it was a hideout of Jean Lafitte, the infamous pirate who volunteered his swashbuckling services to America during the War of 1812. A born showman, Brennan placed lifelike figures of Lafitte and Andrew Jackson in the room where the two devised their winning strategy for the Battle of New Orleans. Then, playing the watering hole’s buccaneer history to the hilt, he mixed up a rum-drenched cocktail called Pirate’s Dream and labeled it “the high brow of all low brow drinks.”

New Orleans took to the concoction like a pirate crew to a treasure chest of gold doubloons. High brows and low brows rubbed shoulders within the tavern’s venerable walls, but it was the proprietor’s flashing smile and welcoming Irish hospitality that won the hearts of Crescent City citizens. All, that is, but one.

Count Arnaud, the owner of an elegant French dinner house, boasted that the Absinthe House might be a popular drinking establishment, but no Irishman could run a restaurant that was more than a hamburger joint.

Feisty Irish American Brennan couldn’t ignore the challenge. In July 1946 he opened Brennan’s Vieux Carre — a restaurant that daringly specialized in French and Creole cuisine! It was a sensation. Society columnists called him the “wonder man” of the New Orleans restaurant industry, pegging his triumph on an “Irish smile and a kiss of the Blarney Stone” and vowing his effervescent personality was “…a blow from which few tourists, writers, movie celebrities or presidents ever completely recovered.”

With the success of Francis Parkinson Keyes’ novel Dinner at Antoine’s (another New Orleans dinner house), Brennan queried, “If dinner at Antoine’s can capture public gastronomic attention, why not breakfast at Brennan’s?” In a February 18, 1950 article entitled “The Happy Irishman of the French Quarter,” Ken Gormin, restaurant reviewer for Collier’s magazine wrote, “…[Brennan has] brought back the three-hour breakfast, a nineteenth-century custom supposedly unfitted to the modern tempo.” Surely Brennan was thinking about the legendary Irish breakfast when he came up with that bit of marketing genius?

Not content with serving his guests sublime cuisine, Brennan was also devoted to the New Orleans community. He served on the chamber of commerce, was the founding chairman of the first New Orleans Tourist Commission, and contributed his driving force to the crime commission where a fellow member, Robert Foster, was extraordinarily fond of bananas. As New Orleans was the fruit’s major American port of entry, Brennan asked his chef to create a special dish for his friend. Today, Bananas Foster is the most requested menu item, with 35,000 pounds of bananas flamed per year to prepare the famous dessert.

In 1954, motivated by an avaricious landlord who demanded half-ownership in the restaurant, Brennan found a new location on Royal Street. After an extensive renovation to the historic structure, the New Orleans society attended a preview dinner on November 1, 1955. It received rave reviews.

Three days later, Owen Edward Brennan, creator of the modern Brunch, passed away in his sleep. Despite their shock and grief, his stalwart Irish American family pulled together and opened on schedule.

Nearly fifty years later as we mark a new millennium, Brennan’s on Royal Street is still going strong, and its breakfast is one of the best in the whole wide world. Sláinte!♦

It”s interesting reading an article similar but more detailed than one I wrote many years ago. New Orleans happens to be a city with which I am very familiar having spent a lot of time there when I was a ship’s officer.

I had plenty of time o study the history of the Irish there which indeed was very interesting.