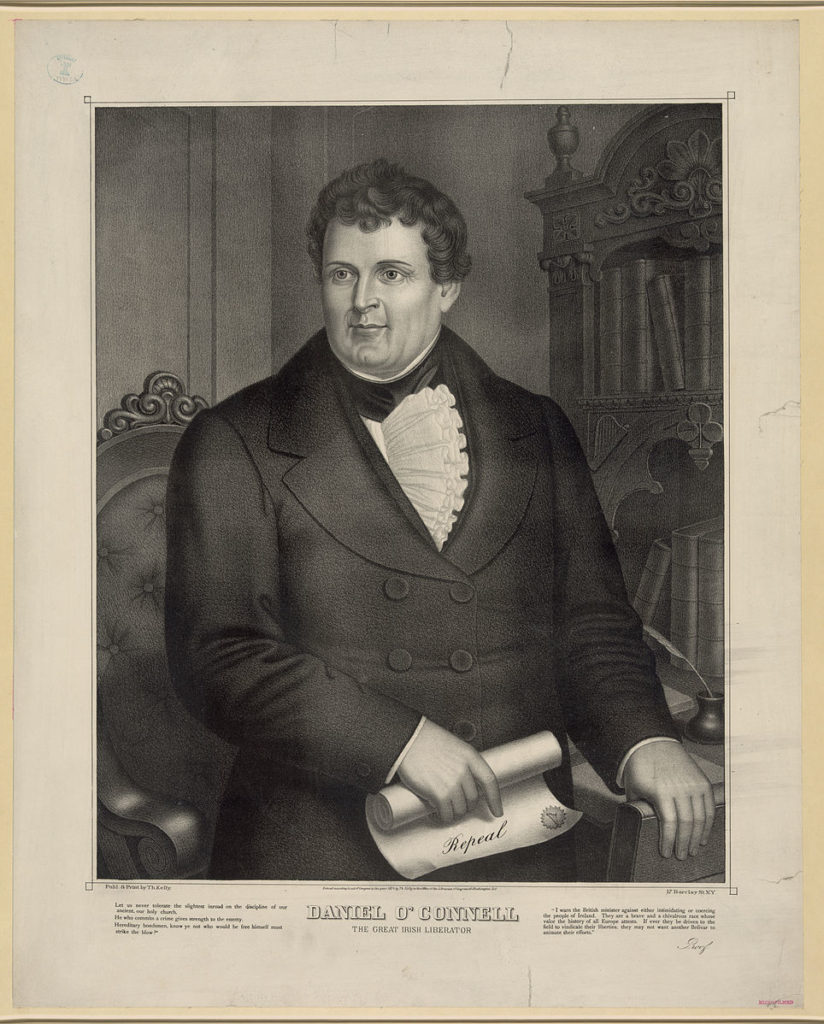

If you had been in London on 15 May 1835, you could have heard Daniel O’Connell, Ireland’s Liberator, speak at a large Anti-Slavery meeting in the prestigious Exeter Hall. O’Connell, the hero of Catholic Emancipation, had established himself as the leading transatlantic opponent of enslavement and as a thorn in the side of American enslavers. But if you had been almost 300 miles west of London on that day, in the small town of Wexford, you might have attended a theatre production of Shakespeare’s ‘Othello’. The audience was described as being ‘enraptured’ by the performance of the young lead actor, Ira Aldridge.

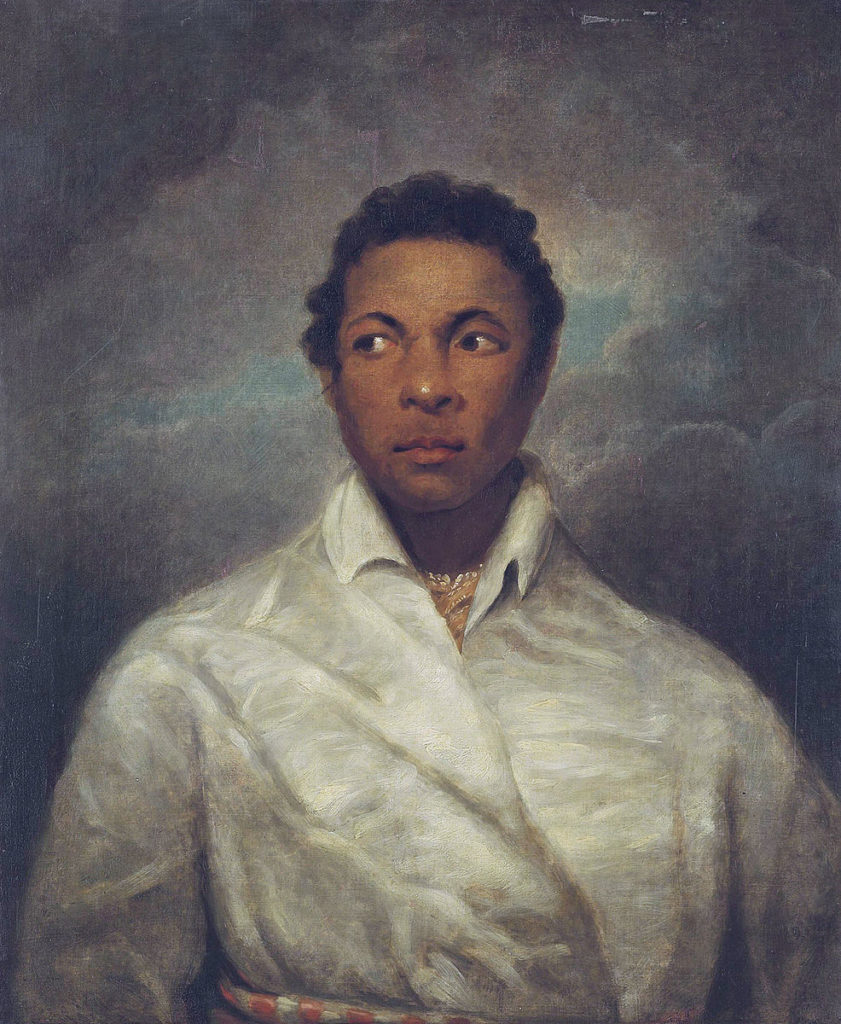

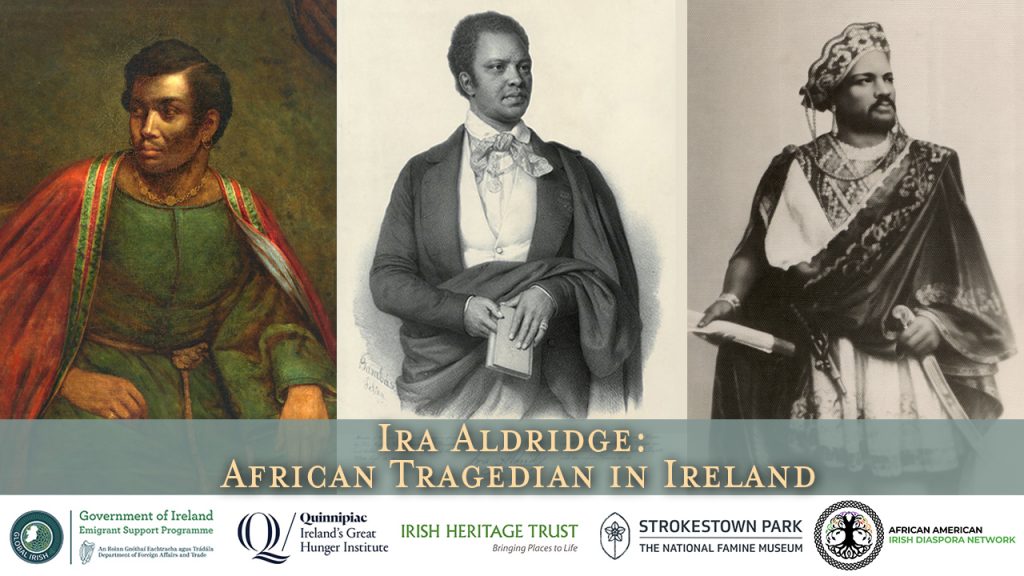

Aldridge was then only 28 years old, an American, Black, and an outspoken critic of slavery. Moreover, he understood that the struggles of black people were part of a wider movement for social justice, which included Ireland’s own struggle for independence and equality. Aldridge was performing in Ireland ten years before Frederick Douglass arrived in the country, but their message was similar. The actor returned to the country many more times, appearing in venues large and small for three more decades, always to packed audiences. Today, however, Aldridge is largely forgotten in both acting and abolitionist histories. Who was this remarkable man, known in his day as ‘the African Roscius’?

While there, Aldridge became enamored with the arts and started to act. Although he was soon employed by the African Grove Theatre, an all-black drama troupe, he found the prejudice and segregation that was part of American theatrical life, even in the northern states, oppressive. So, in 1824, working as the personal assistant of the London-born actor, James William Wallack, Aldridge emigrated to England. He was 17 years old.

Aldridge’s rise to prominence was swift and impressive: he made his debut in London in 1825 appearing as Othello at the Theatre Royal in Covent Garden. It was a role that he would make his own. Critics and audiences started to refer to him as ‘The African Roscius’, a reference to the leading Roman actor of tragedy and comedy. But it was not all plain sailing as a review in the London Times in 1833 demonstrated:

Poor Ira Aldridge was well known to the people of Wexford, and we look back with pleasure to the many delightful hours we spent in his company. He possessed the ease, elegance, and accomplished manners of the well-bred gentleman; was the welcome guest at every social circle, which he enlivened with his wit, humour, and interesting reminiscences …The poetic imaginings of his mind, the richness of his fancy, and the music of his voice present themselves before us in all their early freshness; and not one of his countless friends and admirers deplore his loss more keenly than we do.

Today, Aldridge is remembered in Britain as being the first Black Shakespearean actor. He was also the first actor of African American origin to achieve success on an international stage. But his contribution went beyond simply being one of the foremost actors of the day. At a time when minstrel shows were the most popular form of entertainment on both sides of the Atlantic, Aldridge challenged their offensive caricatures by placing himself very firmly in the centre of high art. By doing so, he subverted and challenged existing ideas of black inferiority, thus reinforcing the arguments being made by leading abolitionists.

African American activist James M’Cune Smith regarded the various contributions of Frederick Douglass, Ira Aldridge, and opera singer, Elizabeth Greenfield (the Black Swan) as being invaluable in the struggle for equality because, by their ‘versatility of talent’, they collectively demonstrated the abilities and skills of the black race, regardless of the obstacles put in their way. While Douglass’s relationship with Ireland continues to be honoured, Aldridge and Greenfield are largely forgotten. For Aldridge, however, Ireland was a special place to perform, and, in Irish theatres, he created a space to challenge racial prejudice and promote the struggle for black justice and equality. ♦

Christine Kinealy’s last book Black Abolitionists in Ireland was published in 2020 by Routledge. It examines ten abolitionists – nine men and one woman – who visited Ireland between 1791 and 1860. Both Aldridge and Greenfield feature in Christine’s forthcoming publications, Becoming Ira Aldridge and Black Abolitionists in Ireland (vol. 2).

Christine Kinealy’s last book Black Abolitionists in Ireland was published in 2020 by Routledge. It examines ten abolitionists – nine men and one woman – who visited Ireland between 1791 and 1860. Both Aldridge and Greenfield feature in Christine’s forthcoming publications, Becoming Ira Aldridge and Black Abolitionists in Ireland (vol. 2).

Christine is the Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University, and is the author of many books and articles on famines in Ireland.

Leave a Reply