Frank McCourt‘s second book, ‘Tis, follows, where Angela’s Ashes leaves off with the young Limerick man making his way in New York. In the following excerpt, Frank’s pal Paddy McGovern takes him to an Irish dance hall.

Paddy Arthur McGovern warns me that if I keep on listening to that noisy jazz music I’ll wind up like the Lennon brothers so American I’ll forget I’m Irish altogether and what will I be then. It’s no use telling him how the Lennons could be so excited about James Joyce. He’d say, Oh James Joyce, me arse. I grew up in the County Cavan and no one there ever heard of him and if you don’t watch your step you’ll be running to Harlem and jitterbuggin’ with Negro girls. He’s going to an Irish dance on Saturday night and if I have any sense I’ll go with him. He wants to dance only with Irish girls because if you dance with Americans you never know what you’re getting.

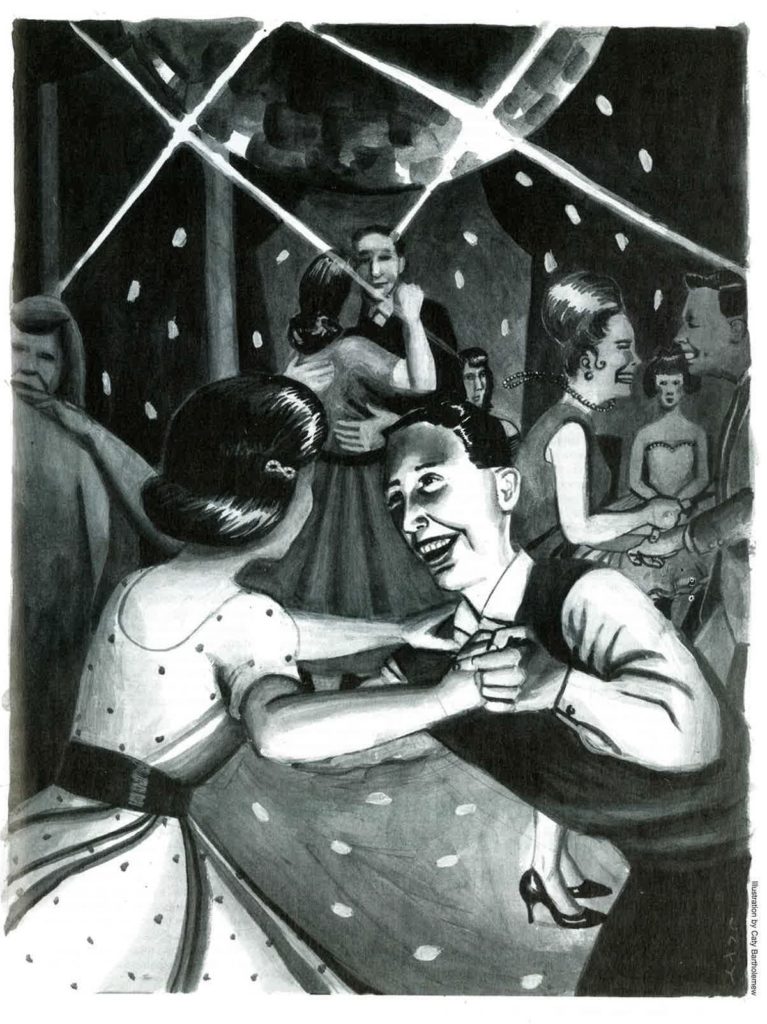

At the Jaeger House on Lexington Avenue Mickey Carton is up there with his band Ruthie Morrissey singing “A Mother ‘s Love Is a Blessing.” A great crystal ball revolves on the ceiling, flecking the ballroom with floating silver spots. Paddy Arthur is no sooner in the door than he’s waltzing around with the first girl he asks to dance. He has no trouble getting girls to dance and why should he with his six feet one, his black curly hair, his rich black eyebrows, his blue eyes, the dimple on his chin, the cool way he has of offering his hand that says, Come up, girl, so that the girl would never dream of saying no to this vision of a man and when they move out on the floor, no matter what class of a dance it is, waltz, fox-trot, lindy, two-step, he steers her around with hardly a glance at her and when he leads her back to her seat she’s the envy of every giggling girl on the seats along the wall.

He comes to the bar where I’m having a beer for the courage that might be in it. He wants to know why I’m not up dancing. Sure what use of coming here if you don’t dance with them grand girls along the wall?

He’s right. The grand girls sitting along the wall are like the girls in Cruise’s Hotel in Limerick except they’re wearing dresses the likes of which you’d never see in Ireland, silk and taffeta and materials strange to me, pink, puce, light blue, ornamented here and there with lacy bows, dresses with no shoulders so stiff at the front that when the girl turns to the right the dress stays where it is. Their hair is trapped with pins and combs for fear it might tumble rich to the shoulders. They sit with their hands in their laps holding fancy purses and they smile only when they talk to each other. Some sit dance after dance, ignored by the men, till they’re forced to dance with the girls beside them. They clump across the floor and when the dance ends move to the bar for lemonade or orange squash, the drink of girl couples.

He’s right. The grand girls sitting along the wall are like the girls in Cruise’s Hotel in Limerick except they’re wearing dresses the likes of which you’d never see in Ireland, silk and taffeta and materials strange to me, pink, puce, light blue, ornamented here and there with lacy bows, dresses with no shoulders so stiff at the front that when the girl turns to the right the dress stays where it is. Their hair is trapped with pins and combs for fear it might tumble rich to the shoulders. They sit with their hands in their laps holding fancy purses and they smile only when they talk to each other. Some sit dance after dance, ignored by the men, till they’re forced to dance with the girls beside them. They clump across the floor and when the dance ends move to the bar for lemonade or orange squash, the drink of girl couples.

I can’t tell Paddy I’d rather stay where I am, safe at the bar. I can’t tell him that going to any kind of a dance gives me a sick empty feeling, that even if a girl got up to dance with me I wouldn’t know what to say to her. I could manage a waltz, oompah, oompah, but I could never be like the men on the floor who whisper and make girls laugh so hard they can hardly dance for a whole minute. Buck used to say in Germany that if you can make a girl laugh you’re halfway up her leg.

Paddy dances again and comes to the bar with a girl named Maura and tells me she has a friend, Dolores, who’s shy because she’s Irish-American and would I dance with her since I was born here and we’d make a good match with her ignorance of Irish dancing and my listening to that jazz music all the time.

Maura looks at Paddy and smiles. He smiles down at her and winks at me. She says, Excuse me. I want to make sure Dolores is okay, and when she’s gone Paddy whispers she’s the one he’s going home with. She’s a head waitress in Schrafft’s Restaurant with her own apartment, saving money to go back to Ireland and this will be Paddy’s lucky night. He says I should be nice to Dolores, you never know, and he winks again. I think I’ll be gettin’ me hole tonight, he says.

Me hole. Of course that’s what I’d like myself but that’s not the way I’d say it. I prefer Mikey Molloy’s way of saying it in Limerick when he called it the excitement. If you’re like Paddy with Irish women jumping into your arms you probably don’t remember one from another and they all become one hole until you meet the girl you like and she makes you realize she wasn’t put into the world to fall on her back for your pleasure. I could never think about Mike Small [Alberta Small, a fellow student on whom he has a crush] like that or even Dolores who’s standing there blushing and shy, the way I feel myself. Paddy nudges me and talks out of the side of his mouth, Ask her to dance, for Christ’s sake.

All that comes out of me is a mumble and I’m lucky Mickey Carton is playing a waltz with Ruthie singing “There’s One Fair County in Ireland,” the only dance where I might not make a fool of myself. Dolores smiles at me and blushes and I blush back and there go the two of us blushing around the floor with little silver spots floating across our faces. If I stumble she steps along with me in such a way that the stumble becomes a dance step and after a while I think I’m Fred Astaire and she’s Ginger Rogers and I whirl her around sure the girls along the wall are admiring me and dying for a dance with me.

The waltz stops and even though I’m ready to leave the floor for fear that Mickey might start a lindy or a jitterbug Dolores pauses as if to say, Why don’t we dance this? And she’s so easy on her feet and so light with her touch I look at the other couples, how cool they are, and it’s no trouble to do it with Dolores, whatever it is, and I push her and pull her and twirl her like a top till I’m sure all the other girls are eyeing me and envying Dolores till I’m so full of myself I don’t notice there’s a girl sitting near the door with a crutch sticking out where it shouldn’t be and when my foot catches in it I go flying into the laps of the grand girls along the wall who push me off in a rough unfriendly way remarking that some people shouldn’t be allowed on the dance floor if they can’t hold their drink. Paddy is at the door with his arm around Maura. He’s laughing but she’s not. She looks at Dolores as if to sympathize with her, but Dolores helps me to my feet, asking me if I’m all right. Maura comes over and whispers to her and turns to me.

Will you take care of Dolores? I will.

She and Paddy leave and Dolores says she’d like to leave, too. She lives in Queens and she says I really don’t have to see her all the way home, the E train is safe enough. I can’t tell her I’d like to take her home in the hope she might ask me in and there might be some excitement. She surely has her own apartment and she might feel so sorry about the way I tripped over the crutch she wouldn’t have the heart to turn away and we’d be in her bed in no time, warm, naked, mad for each other, missing Mass, and breaking the Sixth Commandment over and over and not giving a fiddler’s fart.

When the E train rocks or stops quickly we’re thrown together and I smell her perfume and feel her thigh against mine. It’s a good sign when she doesn’t pull away from me and when she lets me hold her hand I’m in heaven until she starts talking about Nick, her boyfriend in the navy, and I put her hand back in her lap.

I can’t understand the women in this world, Mike Small who drinks beer with me in Rocky’s and then runs to Bob, now this one who lures me onto the E train all the way to the last stop at 179th Street. Paddy Arthur would never have put up with this. Back at the dance hall he would have made certain there was no Nick in the navy and no one at home to interfere with his all-night plans. If there was any doubt he’d have jumped off the train at the next stop, so why don’t I? I was soldier of the week in Fort Dix, I trained dogs, I go to college, I read books, and look at me now sneaking through the streets around NYU to avoid Bob the football player and taking a girl home who’s planning to marry someone else. It seems everyone in the world has someone, Dolores her Nick, Mike Small her Bob, and Paddy Arthur is well into his night of excitement with Maura in Manhattan and what kind of a bloody fool am I traveling to the end of the line?

I’m ready to jump off at the next stop and leave Dolores entirely when she takes my hand and tells me how nice I am, that I’m a good dancer, too bad about the crutch, we could have danced all night, that she like the way I talk, the cute brogue, you can tell I was well brought up, it’d so nice that I go to college, and she doesn’t understand why I’m hanging around with paddy Arthur who, it was easy to see, had no good on his mind with respect to Maura. She squeezes my hand and tells me I’m so nice to travel home with her and she’ll never forget me and I feel her thigh against mine all the way to the last stop and when we stand top leave the train I have to bend to hide the excitement that’s throbbing in my trousers. I’m ready to walk her home but she stands by the bus stop and tells me she lives further out, in Queens Village, and really, I don’t have to go all the way, she’ll be all right on the bus. She squeezes my hand again and I wonder if there’s any hope that this might be my lucky night and I’ll wind up wild in bed like Paddy Arthur.

While we wait for the bus she holds my hand again and tells me all about Nick in the navy, how her father doesn’t like him because he’s Italian and calls him all kinds of insulting names behind his back, how her mother really likes Nick but would never admit it in case her father might come home in a drunken rage and smash the furniture which wouldn’t be the first time. The worst nights are when her brother, Kevin, visits and stands up to her father and you wouldn’t believe the swearing and the rolling on the floor. Kevin is a linebacker at Fordham and a good match for her father.

What’s a linebacker?

You don’t know what a linebacker is?

I don’t.

You’re the first boy I ever met who didn’t know what a linebacker is.

Boy. I’m twenty-four years old and she’s calling me a boy and I’m wondering do you have to be forty to be a man in America?

All along I’m hoping that things are so terrible with her father she might have her own place but, no, she lives at home and there go my dreams of a night of excitement. You’d think a girl her age would have her own place so that she could invite the likes of me who see her to the end of the line. I don’t care if she squeezes my hand a thousand times. What’s the use of having your hand squeezed on a bus in the middle of the night in Queens if there’s no promise of a bit of excitement at the end of the journey?

She lives in a house with the statue of the Virgin Mary and a pink bird on the little front lawn. We stand at the small iron gate and I’m wondering if I should kiss her and get her into such a state we might go behind a tree for the excitement but there’s a roar from inside, Goddammit, Dolores, get your ass in here, hell of a nerve you have coming home at this goddam hour and tell that goddam shithead run for his life, and she says, Oh, and runs inside.

By the time I get back to Mary O’Brien’s everyone is up and having bacon and eggs followed by rum and slices of pineapple in heavy syrup. Mary puffs on her cigarette and gives me the knowing smile.

You look like you had a good time last night.♦

Read Patricia Harty’s interview ‘Tis Frank with Frank McCourt.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the January 2000 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply