“I am not going to give you any taffy!”

The charismatic and powerful public speaker who pushed for equal pay for equal work, better labor standards, and overall empowerment for women is profiled by Rosemary Rogers.

Leonora O’Reilly was born in 1870 to parents driven out of Ireland by the potato famine only to live in poverty in New York’s Lower East Side. Her father and brother died early in her childhood and her mother, Winifred, worked in a garment center sweatshop that didn’t pay enough for food. Leonora left school at 11 and joined Winifred both in the garment center and at union meetings.

She worked 60 hours a week for wages that, for reasons only known to her bosses, were soon cut in half. It was a rotten childhood but it birthed a righteous fury that energized Leonora. Later in her life she drew on her past to blast the men of the U.S. Congress, a group with wealth, stay-at-home wives, a group unaware of any other reality beyond their cossetted lives.

“You men say to us: ‘Your place is in the home,’” continuing, “yet as children we must come out of the home at 11, at 13, and at 15 years of age to earn a living; we have got to make good or starve.”

At the age of 16, Leonora joined the Knights of Labor, the only labor organization that allowed female workers. Her energy was matched only by her moxie – in short order she founded the Working Woman’s Society to investigate and reform the working conditions of woman. It was during this time she developed a following of powerful reformers and philanthropists who saw great potential in the tireless Miss O’Reilly and arranged for her to go back to school, studying textiles and social theory.

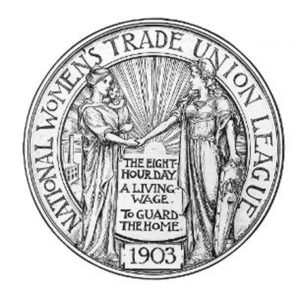

She became a socialist, suffragist, anti-war activist, cofounding member of both the NAACP and the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). Membership in the WTUL included working women without money and wealthy women who had plenty. The “Mink Brigade,” as the well-heeled were called, could be patronizing toward their hard-working sisters, an attitude that sometimes incited Leonora to quit the WTUL in a huff. But the organization wanted, needed her back: She was the WTUL’s most successful recruiter, drawing crowds on street corners and arenas, with her oratorical skill, passion and especially, charisma.

Leonora marched with the strikers in a 1910 protest “The Uprising of the 20,000,” a revolt against the working conditions in the garment industry. The sweatshops were, in effect, Slavery New York Style, nowhere more evident than in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. Triangle demanded 16–20-hour workdays in dangerous, unsanitary conditions, no safety precautions, no bathroom breaks and talking was strictly forbidden. Even humming could get you fired on the spot. The fire exits were locked from the outside to keep pesky union organizers out.

On March 25, 1911, fire broke out and trapped workers, mostly immigrant teenage girls, in an inferno that left 146 dead. Leonora was in the crowd that saw girls burning alive then hitting the street in a steady volley of thuds. It was a tragedy that shocked the city to its core; hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers gathered for the mass funeral.

O’Reilly helped mobilize support for an investigation that brought the Triangle owners to trial for manslaughter. The jury found them not guilty, a verdict that always haunted

Leonora. The following year she gave a speech to the House Judiciary Committee. “We, of New York remember the Triangle fire case. We saw our women burning, jumping to the streets, and dying horrible deaths. We tried to get justice but got instead the same old verdict from the courts, ‘Nobody to blame.’”

But after the horror, came reform. Al Smith, another Irish American and head of New York’s State Assembly pushed through a flood of progressive legislation enforcing government safety regulations and regular inspections of factories. 56 bills were passed in 1913 alone. Business leaders were outraged.

It’s exhausting just to keep score of her activism. She took on the cause of workers, women’s suffrage, African Americans, Native Americans and peace – she was a delegate to the Hague Women’s Peace Conference in 1918. She paid tribute to her heritage by joining the fight for Ireland’s independence. O’Reilly used her contacts to drive support for boycotts, the first a boycott by dockworkers who refused to unload British cargoes across major American cities. Later, O’Reilly was involved in a consumer boycott of British goods, using her connections with the Women’s Purchasing League.

She brought together her twin passions, women suffrage and the rights of working women when she founded the Wage Earner’s Suffrage League. Other suffrage organizations, Leonora believed, marginalized working women who “needed the ballot for to save their very lives.” She urged young, uneducated, poor women in the League to seize agency and be outspoken in the fight against oppression. She stood outside factories speaking and handing leaflets to women that asked a question, still asked today, “Why are you paid less than a man?” In 1912, she brought together working women and suffragists in a massive rally of sisterhood that transcended class.

Ida Tarbell, the famous muckraker who broke up the Standard Oil monopoly, found herself in Miss O’Reilly’s crosshairs. Leonora saw Tarbell as merely an “observer and critic” of the women’s suffrage movement, not using her reputation and reporter skills to join the movement. Tarbell, who took down a Rockefeller and ushered in anti-trust legislation, preached that a woman’s place was in the home, her true role was wife and mother. Leonora wasn’t surprised by her attitude – Ida wasn’t a wage earner “serving a life sentence in our industrial system.” For Leonora it all came down to being a worker.

In 1912 she gave her famous “Taffy” speech – she was the star witness at a joint Senate committee on women’s suffrage and representing the country’s eight million working women. Her hard-hitting speech attacked the all-male committee.

“I am not going to give you any taffy.” She continued with eerily prescient words, still relevant in 2021, “You men in politics are not leaders, you follow what you think is the next step on the ladder.” Her closing sentence was nothing less than an order, “We want you to understand that the next step in politics, the next step in democracy, is to give to the women of your nation a ballot.”

When she was 37, she adopted a baby daughter, Alice, adding Single Mother to her hefty resumé. Tragically, and evoking the losses Leonora and Winifred suffered years ago, Alice died at 5. Leonora and Winifred, who always lived together, had doted on the child and were devastated. But, no strangers to sorrow, they carried on.

Finally, Leonora’s exhausted body just gave out, she stayed in her Brooklyn home. On most Saturdays, her comrades, her sisters – hellraisers all – came to her Brooklyn home to talk politics, unions and literature. When Leonora passed at age 57, social reformer Mary Dreier wrote a memorial poem for her, “You held the torch aloft when we were young…Your passionate faith and fervor drew us on.” ♦