“The Greatest Living Irishwoman”

– George Bernard Shaw

Writer, playwright, folklorist, and co-founder of The Abbey Theatre, Isabella Augusta, Lady Gregory, née Isabella Augusta Persse, (born March 15, 1852, Roxborough, County Galway, Ireland – died May 22, 1932, Coole, did much to preserve Ireland’s forgotten history.

Toward the end of the 19th Century, Queen Victoria, or so it seemed, wandered the west of Ireland from farms to cottages to the Workhouse asking questions of Catholic peasants: she wanted to hear the tales passed down from generations, their songs, myths and visions. She had even learned the Irish language to better capture the nuances of folklore and the beautiful rhythmic sentences. The peasants soon realized Queen Victoria was really their landlady from the “Big House.”

Lady Augusta Gregory, descended from Anglo-Irish aristocracy, may have resembled Victoria but the similarity ended there. Augusta identified as Irish and had re-invented herself as a folklorist, one determined to salvage and preserve Ireland’s forgotten history. After the wars of the 17th Century, much of Irish culture had been annihilated, knowledge of its history fragmented and the Gaelic language outlawed in schools. Then the famine that killed so many Irish killed their stories along with them. Lady Gregory made it her mission to take an oral history of the people of the west, write a narrative of faeries, ghosts, banshees and saints; she also immortalized their history of British tyranny, dead heroes and starvation.

Isabella Augusta Persse was born in 1852 on an estate, named Roxborough, in Galway, into a large family and its designated spinster. She surprised everyone when, in 1880, she married Sir William Gregory after falling in love with his library. Sir William, a wealthy widower, lived at a neighboring estate, Coole Park. She was 27, he was 63. Augusta hadn’t heard that her bridegroom, a member of Parliament during the famine, had been particularly vicious to the starving of his country, even those outside his front door.

Gregory died within two years but Augusta still managed to have a son, Robert, and a love affair during the brief marriage. (In his biography of W.B. Yeats, R.F. Foster repeated a Gort legend that the father of Augusta’s son was not the elderly Sir William, but a young blacksmith, Seanín Farrell, who had been approached to father the child and then helped to emigrate to America.)

Honeymooning in Egypt, the Gregory’s met Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, a handsome (and married) poet, adventurer and virulent anti-Imperialist. Her lover drew Augusta into his worldview, one quite at odds with that of her husband and upbringing. Blunt’s support for Irish causes led to his imprisonment in Dublin’s Kilmainham Gaol and his support for Egyptian independence had him thrown out of the country. He both inspired her Irish nationalism and encouraged her to write, which she did, twelve sonnets dedicated to him, bursting with love and passion, “Pleading for your love which now is all my life…”

After Lord Gregory’s death, Augusta wore only black for the rest of her life, but she hardly shrank into widowhood (or, for that matter, mourning). Rather, she took off like a comet, as only a 30-year-old widow with financial security and a great dream, could. Just as she was now born again, she would see Ireland born again. She would revive Ireland’s literary heritage, her ancient mythology and bring back the Gaelic language. She wanted Ireland to regain her “dignity” after centuries of oppression and, in the words of Robert Emmet, “take her place among the nations of the earth…”

She energized the vast supply of talent that had emerged at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th Century, a movement that became the Irish Literary Revival. The Revival was aligned with the Gaelic League, formed in 1893 by Douglas Hyde to rescue the Gaelic language. “Irish,” she would write “is the most ancient vernacular literature of modern Europe…its first speakers were early farmers who arrived in 4500 BC.”

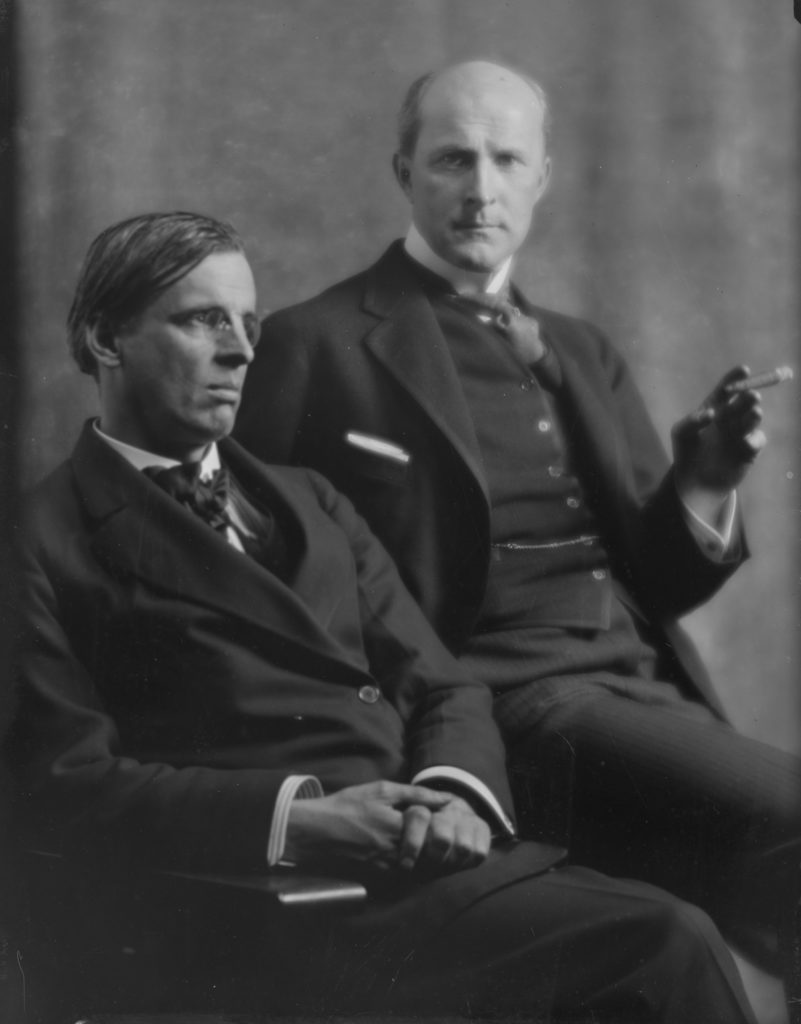

She became fascinated with the poet William Butler Yeats after reading his book The Celtic Twilight, his own collection of folklore infused with mysticism and spirituality. When Augusta met him, she described him as “egregiously the poet” sporting a large black bow and wrapped in a long trailing cloak. He was good friends with Douglas Hyde whose recent speech on “De-Anglicizing” Ireland was so powerful, it’s been credited with the founding of the Sinn Féin. One auspicious evening in 1894, Yeats and Douglas Hyde visited Lady Gregory at Coole.

That night, Hyde read aloud the Gaelic poems and songs he had translated into Tudor English. His translation still held on to Gaelic rhythms and alliteration so suited the Irish voice. Yeats listened, it was English yet not-English, at that moment he decided to write his poetry with a Gaelic affect. That night, too, the profound, symbiotic relationship between the Lady and the poet began.

She, 13 years older and of a higher social class, always called him “Willie” while he never addressed her as anything other than “Lady Gregory.” But, as one onlooker remarked, “As soon as her terrible eye fell upon him, I knew that she would keep him.” And keep him she did, despite his unrequited love for the fervid nationalist Maud Gonne, despite his later marriage and children, despite his world fame, she and Coole would always be his spiritual center.

She wrote with him, translated for him, sometimes supported him and doted on him to almost embarrassing lengths. Her cousin, Sir Ian Hamilton described Yeats at Coole: “No one can even walk along the passage on either side of Yeats’s door …thick rugs were laid out to prevent the slightest sound from reaching the Holy of Holies…” Robert, her son, resented the continued presence of the poet and really resented all the vintage wine Augusta and Willie put away during their long evenings. Even upstart James Joyce got snarky. Speaking of the duo, he wrote to his brother, “W.B. Yeats ought to marry Lady Gregory – to kill all the talk.”

Augusta, Yeats and Douglas Hyde made Coole the epicenter of the Revival; they were later joined by Edward Martyn, George Russell (“AE”) John Millington Synge, George Moore, Annie Horniman and the Fay Brothers. Determined to sideline “The Irish Question” this group of Catholics and Protestants had a singular focus: to create an Irish identity and culture independent of Britain built on its shared roots and ancient history. In 1904, they founded Dublin’s Abbey Theatre to realize that dream while sidestepping the unending, uneasy tension between the British Empire and her most troublesome colony.

Though Annie Horniman did most of the financing, the Abbey’s patent was signed by Lady Gregory, putting her at the helm where she wrote and directed many of the performances. She showed a surprising gift for comedy – her plays, “Spreading the News” (1904), “The Rising of the Moon” (1907) and “The Workhouse Ward” (1908), got the theatre going. She was tireless, filling in for any and all, sometimes served as usherette – Shaw called her “the charwoman of the Abbey.”

Two years after the opening, Yeats told Augusta of a dream he had “almost as distinct as a vision, of a cottage …and into the midst of that cottage there came an old woman in a long cloak.” The woman, according to Yeats was “Ireland herself, that Cathleen ni Houlihan for whom so many songs have been sung.” Cathleen told her sad story about the loss of her “four beautiful green fields” (the four provinces of Ireland). It may have been Willie’s dream but it was Augusta who wrote the play for which she received no credit, something she admitted was “rather hard on me.” (She did surreptitiously assert authorship, writing on margins of the script, “All this is mine alone.”)

Lennox Robinson, writer and future head of the theatre said “Cathleen Ni Houlihan” and Augusta’s “The Rising of the Moon” “made more rebels in Ireland than a thousand political speeches or a hundred reasoned books.” Now the Abbey could no longer stay apolitical, “The Irish Question” had moved front and center.

There was talk of rebellion in the streets of Dublin and other parts of the country, all of which put Lady Gregory in something of an awkward position. A nationalist and Gaelic speaker she was still a landlord. How could she reconcile her personal life when political rebellion was on the horizon? She did something unexpected and reckless: she put on the plays of John Millington Synge. They were reality-based and a radical departure from Abbey’s comedies and mythologies. Synge was going to cause controversy.

She staged Synge’s “Riders to the Sea,” “Shadow of the Glen” and in 1907, “The Playboy of the Western World,” the play that caused the ruckus heard round the western world. The story, written in a stylized peasant dialogue, told of one Christy Mahon who wandered into a strange village, claiming he had killed his “Da,” a lie that brought him hero worship until the dead “Da” shows up. The plot of patricide and some a mention of ladies’ underwear ran counter to Irish prudery. The audiences threw potatoes, tomatoes and even rosaries at the stage. Lady Gregory would not abide censorship: She walked onstage, directly addressed the actors, ”Keep playing” and the show went on.

“Playboy” moved to New York and took controversy with it. This time when the audience acted up, she hid on stage (behind a prop), again telling the actors to keep going. But the real “Playboy” trouble came in Philadelphia, where the entire cast was arrested, thrown in a paddy wagon and taken off to jail. A lawyer, John Quinn, contacted Lady Gregory, offering his services and putting a meta spin on the whole affair, wrote, “The policemen that ought to be put in the theater ought to be Irish policemen; then the town would have the edifying spectacle of Irish policemen ejecting Irish rowdies from an Irish play. I have not seen anything like the bitterness or unfairness of these attacks both by Irish ignoramuses and abnormal churchmen since the last days of Parnell.”

In a short time, John Quinn, young lawyer, and Lady August Gregory, impresario and grandmother were absolutely and madly in love. Much like she did with Blunt earlier, she penned florid love letters, …dear John, my own John, not other people’s John, I love you, I care for you, I know you, I want you, I believe in you. The lovers commuted between Dublin and Philadelphia and remained lifelong friends. Quinn continued to be a great supporter of Irish writers, both financially, and legally, defending James Joyce’s Ulysses against obscenity charges in the New York courts.

As the events of 1916 unfolded, Dublin was the center of the action, cast and crew members joined in the fighting and the first rebel killed was an Abbey Player, Sean Connolly. Both Lady Gregory and Yeats were opposed to violence but when the 16 leaders of the rebellion were executed, they, like the rest of Ireland, were outraged. Formerly indifferent, they were now supporting the rebels and condemning the British.

In the past, besotted as he was, Yeats always ignored the pleas of Maud Gonne to embrace radical nationalism. He preferred his own romantic nationalism to her dreams of insurrection. Now he wrote Lady Gregory “I had no idea that any public event could so deeply move me” – the summary executions of the Rising leaders did what Maud could not, he was transformed. Or as he put it in verse, he was “changed, changed utterly.”

“Easter 1916,” only 80 lines long, is arguably Yeats’ greatest poem. He still seemed in a state of shock over the bravery of the rebels, the barbarity of the British and questions his guilt about Cathleen ni Houlihan, asking, “Did that play of mine send out/ Certain men the English shot?” What he couldn’t have realized was the events of 1916 set in motion the disintegration of the greatest empire the world had ever known. Once Ireland, its first colony departed, the others fell like dominoes, all the pink blobs on the map kept shrinking and disappearing.

At the same time, unbearable sorrows came into Lady Gregory’s world. Her beloved nephew, Hugh Lane, died on the Lusitania in 1915. Her son, Robert, an Ace in the Royal Flying Corp was fighting at the Italian Front when, in 1918, his plane was shot down. Robert left a widow, three children and a mother who would never recover from the loss. Yeats created a poem for Robert, “An Irish Airman Foresees His Death” and the poet’s nationalism is manifest, the airman was fighting in a war that was not his, it was a British war.

At the same time, unbearable sorrows came into Lady Gregory’s world. Her beloved nephew, Hugh Lane, died on the Lusitania in 1915. Her son, Robert, an Ace in the Royal Flying Corp was fighting at the Italian Front when, in 1918, his plane was shot down. Robert left a widow, three children and a mother who would never recover from the loss. Yeats created a poem for Robert, “An Irish Airman Foresees His Death” and the poet’s nationalism is manifest, the airman was fighting in a war that was not his, it was a British war.

“Those that I fight I do not hate,

Those that I guard I do not love”

The dark days continued. Her childhood home, Roxborough, burnt down, her daughter-in-law, who had the legal right to do so, wanted to sell Coole. When Yeats married a fellow occultist, George Hyde-Lees, Augusta knew the marriage would supplant her in Yeats’ life. Then came the Irishman against Irishman, civil war.

But ever-resilient, ever-resourceful, Augusta rallied, due in large part to a socialist, labourer, resident of the tenements, and former political prisoner of the Easter Rising, playwright Sean O’Casey. He was the Abbey’s newest sensation, a man of the streets who wrote of the working classes and moved seamlessly from the vernacular to biblical language. Lady Gregory adored him and it was mutual. He named her Blessed Bridget O’Coole, “a nun of a new order a blend of the Lord Jesus Christ and of Puck.

The civil war had ended and the newly formed Irish Free State subsidized the Abbey. This made those on the other side of the civil war biased against the Abbey and its work. O’Casey’s first success was the 1923 “Shadow of the Gunman,” followed by “The Plough and the Stars,” and “Juno and the Paycock.” The last play featured a prostitute which brought the audience, to its feet and ready to riot. Yeats, in a fever, came to the stage, “You have disgraced yourselves again. Is this to be an ever-recurring celebration of the arrival of Irish genius?”

In 1922 the fortunes of Willie and Lady Gregory went in different directions, he was now a wealthy, famous Senator while she was still struggling to hold on to Coole. Politically, the poetic vagabond had moved to the right while the lady from the great house had moved to the left. When Yeats won the Nobel Prize in 1923, he announced the prize should be shared with two others, the (deceased) Synge and the (alive) Lady Gregory. Then, as was his wont, he got bitchy, describing his dear friend and patron, as “as an old woman sinking into the infirmities of age.” (But, it should be noted that, when she passed, he mourned her greatly, “my sole advisor for the greater part of my life.”)

Yeats’ Nobel aside, the shining star of the Literary Revival was a young latecomer, one Lady Gregory once described as “the spectre of the new generation.” James Joyce may have kept his distance from the original group but his masterpiece Ulysses was still in their tradition – it was based on an ancient myth. The book introduced modernism and is still considered the greatest work of prose in the English language.

Ireland’s literary revival created a powerful sense of national identity proclaiming the small island’s single ancient culture – regardless of religion. It now drew on it its own language, art, customs, mythology and history. Despite the factions, north and south, the revival proved the country had more in common than they realized. The “Anglo” from Anglo-Irish was, in time dropped, a quaint remnant of colonialism. ♦

Today Coole Park is a nature reserve, open to visitors, offering free admission and even a tearoom. There’s a walled-in park that encases a copper beach tree saved from the estate of Lady Gregory. The initials of Douglas Hyde, George Bernard Shaw, Sean O’Casey, WB Yeats, J.M. Synge, AE, and so many others ae still there. Only missing are the initials of the woman who made everything happen, the woman never given to self-promotion, Lady Augusta Gregory.