What help can poetry be during a pandemic?

This summer it feels like Ireland needs Americans and Americans need Ireland more than ever. I have visited Ireland close to twenty times since my first trip there in the late 1970s, drawn by the country’s remarkable beauty, justly famous hospitality, and, during the 90s, by my interest in American involvement in the Northern Ireland peace process.

On this trip, traveling to Ireland was dramatically different. Since July 22, fully vaccinated Americans traveling to Ireland are not required to quarantine. However, our small group arrived earlier in July when inside dining and drinking was prohibited, removing one of the great joys of the Irish experience – the music and overall conviviality that constitutes “the craic” in any good Irish pub.

I have always come to Ireland for the same reason that millions of other Americans do, but also for literature and poetry. This time I brought along my favorite book of poems by Seamus Heaney, The Spirit Level, published in 1996. I read through the poems on the flight from Chicago to Dublin with only 40 passengers on board, with time and space to stretch out and to take in Heaney’s reflections on death, everyday courage, endurance, and the source of artistic inspiration.

Several poems included in The Spirit Level: “St Kevin and the Blackbird,” “Keeping Going,” “At the Wellhead,” and “Tollund,” all seemed to speak to the moment we were living through even though they were written about other times and places.

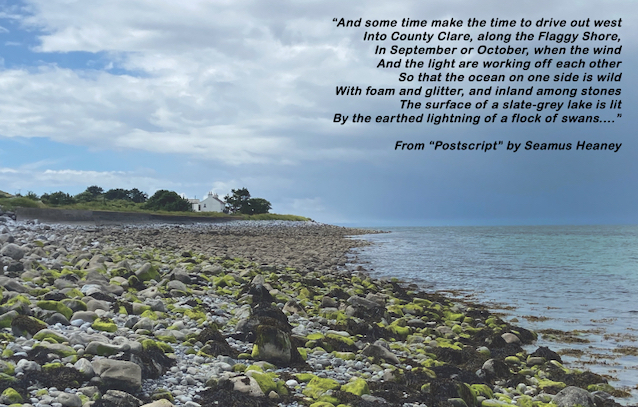

The primary destination for what I wanted to be a literary adventure was the Flaggy Shore, in County Clare, the beautiful strand that inspired the poem “Postscript,” which ends the book.

Our group warmed up for our journey into the west by exploring the streets of Dublin. During our first morning walk near our hotel up and down Baggot and Leeson Streets, to Merrion Square, and along the Grand Canal, we looked for the commemorative plaques affixed to the outside walls of the Georgian townhouses announcing that an Irish writer or artist was born or lived there.

We had a contest to see who could notice the plaques first and then tell something about the poet, writer, or painter to inform the other members of the group. We found the homes of W.B. Yeats, Francis Bacon, Elizabeth Bowen, Oscar Wilde and also came across a half dozen bronze statues.

Poet Patrick Kavanagh sat stoically on a bench overlooking the canal near the Baggot Street Bridge. James Joyce seemed to look quizzically at the stainless-steel spire on O’Connell Street, and rocker Phil Lynott held forth – and held his guitar – in front of McDaid’s pub, just off Grafton Street. There were extra points if you could recite a few lines from “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” or sing the chorus to “Whiskey in the Jar.”

On Mount Street Crescent next to a Starbucks, I was surprised and delighted to see two bronze statues side by side, one of playwright Brian Friel and the other of writer John B. Keane, the Keane statue is at least a foot taller than Friel’s. A custodian who was cleaning up the area enthusiastically talked about Friel’s plays Translations and Faith Healer, which he had seen at the Abbey and Gate Theatres.

I told him that in the United States there had been an intense controversy over some of our statues and that it might have been better if we had erected more of them – like Ireland had – to honor artists, and fewer honoring confederate generals.

The Seamus Heaney exhibit across from Trinity College was open and accessible. I visited there two years ago and wrote about it for Irish America, and went back again to buy more of the pencils they sell with the name of the exhibit – “Listen Now Again” – etched on the side. In typical Irish fashion, when I asked for five pencils the receptionist threw in two for free, asking me as I paid to encourage President Biden to visit the exhibit. I assured her I would.

The main reason for visiting the Flaggy Shore was that I wanted to take my teenage nieces to where “Postscript” was formed and read the poem out loud as a kind of conjuring of Heaney’s spirit. I began to appreciate Irish poetry and writing when I was in college, but I wanted them to have a head start at making their lives more magical and creative by seeing the place where “Postscript” was created.

Heaney described the richness of the Irish landscape in a way that I knew would deepen our own understanding of what we were seeing.

In his essay “The Sense of Place,” Heaney writes about how a place can be experienced viscerally, “illiterate and unconscious” about its history or function for the local community. An alternative approach is learned and literate, creating a “poetic tension” between these two modes of understanding.

Heaney described many of his poems as a “memory bank” of historical trauma, tied to the ground by bloody events, while others grasp at a “system of reality beyond the visible realities” a spiritual dimension just out of reach of our perceptual grasp.

“Postscript,” was occasioned by a visit that Heaney and Brian Friel and their wives Marie and Anne had made to see Mt. Vernon, Lady Augusta Gregory’s summer home on the small peninsula between Ballyvaughan and Kinvarra.

On the drive to The Flaggy Shore, I had my nieces read from The Spirit Level, with the suggestion that rather than trying to interpret any particular poem – they should relax and take in the rhythm and music of the words.

We arrived at the Flaggy Shore in the early evening. The sun moved slowly above the ocean horizontally rather than “sinking” into the sea like we were used to seeing at our home in California. Dark clouds drifted lazily in the distance over Galway, whispering that they were headed our way.

Several locals waded and swam in the small bay. Dogs ran free chasing birds up and down the beach.

In the poem, Heaney wrote of the wind and light “working off each other,” and a flock of swans with feathers “white on white” with their heads moving “busy underwater.” He pivots from a precise description of the surroundings to how the combined impact of environment, perception, and emotion created an opening for creativity. The poem, Heaney implies, came from a place of immense mystery, unforced and “useless” to attempt to replicate.

“You are neither here nor there,” Heaney writes, merely a convenient vessel through which “known and strange things pass.”At the end of the poem, Heaney’s heart, caught “off guard” and buffeted by the ecstatic moment, is blown open.

In the book Stepping Stones, conversations with fellow poet Dennis O’Driscoll, Heaney said the inspiration for the poem felt like “a ball kicked in from nowhere” a visitation induced by the “glorious exultation of air and sea and swans.”

Heaney also stated that the poem was in some ways a dialogue with W.B. Yeats’s poem of loss “The Wild Swans at Coole.” Yeats’ swans are mysterious, beautiful and with hearts that “have not grown old,” a sentiment that Heaney echoes in “Postscript.”Heaney’s swans, in literary critic Helen Vender’s summary, are not paired “lover by lover,” as with Yeats, but are “communal and practical,” bent to their life-sustaining work.

I read “Postscript” to my nieces, trying to add drama by emphasizing the words “wind,” “wild,” “roughed,” “strange,” “buffetings” and “blow,” to see if I could catch their hearts off guard.

After the reading, we walked to Lady Gregory’s home – now a bed and breakfast – one hundred yards down the strand. I knocked on the door with the idea of asking for a quick tour but no one answered. With a friend, I wandered the grounds that could not be much different than they were in Yeats’ time.

Seamus Deane, Heaney’s childhood classmate and literary scholar – who passed away last May – regarded The Spirit Level as part of Heaney’s artistic and personal evolution towards poems of lightness, lift and even hope. Deane describes the shift in his essay “The Famous Seamus,” as “moving off the sucking, dragging ground and into the air. …from dispute, clamor and violence to serenity, oracularity, and wisdom.”

In his 1995 Nobel Lecture, “Crediting Poetry,” Heaney reflected upon the brutalities and violence of history and his own brief flirtation with the notion – a thought experiment – that violence might be the only way to break the grip of political repression. Sensitive to the “wounded spots” around the world and particularly the brutalities of Northern Ireland, he described his eventual escape into ritual contemplation, spending years “bowed to the desk like some monk” impotent to create any real change.

Heaney eventually “straightened up” from his desk, he told his Nobel audience, and created a space in his imagination for “the marvelous as well as the murderous.” The Spirit Level was published the year after his Nobel Prize, and it is the poems of endurance, hard work, and stoic commitment that anchor the book.

Heaney transformed the twelfth-century tale about an Irish saint into the poem “St Kevin and the Blackbird.” St Kevin must keep his arms outstretched for weeks, like a “crossbeam” after a blackbird lands in his upturned hand and lays an egg. His agonizing task is complete only after life is affirmed and renewed when the hatched young bird flies away, the “trapped energy” of both poem and bird released.

In the poem “Keeping Going,” written for his brother Hugh, Heaney praises his brother for “stay[ing] on where it happens,” with “good stamina” at home on the farm in Northern Ireland despite bad omens, dark portents, and random murder. Hugh “cannot make the dead walk” or even right a minor wrong, and he momentarily wonders what the point of his life is before moving forward. What Hugh can do is help his community, using his big tractor to keep “Old roads open by driving on the new ones.”

Hugh attests to the imperative of tenacity, goodwill, and humor for keeping bitterness at bay and affirming the power of friendship.

As we left the Flaggy Shore, I thought of the poem “Tollund,” a post-IRA ceasefire poem that Heaney described as “the world of the second chance.” Every place we had traveled in Ireland we had met people who were trying, as the poem encourages, to “make a go of it, alive and sinning, Ourselves again…”

It is impossible to read these poems while in Ireland and not reflect on the difficulties of the moment, the death and economic hardship that the Irish – and everyone – have faced over the past year and a half. Heaney was always hesitant to make great claims for the political or economic potential of poetry, but he did retain his faith that poetry and art might remind us that we are “hunters and gatherers of values,” that are constantly threatened.

Ultimately, I believe, Heaney asks us all to “Imagine being Kevin,” called to fulfill a task despite the doubts we might have about our strength to complete it.

On the drive back to Dublin, Sophia, one of my nieces, said that she had just started reading poetry in her high school English class and that “experiencing the site where one of the world’s greatest poets was inspired was magical.” My strategy had worked. She called me a “funcle,” a fun uncle, and making poetry “fun” is not easy.

Heaney thought the landscape was a manuscript that we had to learn to read again, afraid that we may have lost the talent for describing where we live. Before leaving Dublin for Los Angeles, I started to make a list of places where, when I return again, I could bring others to read a poem or story, like at the Flaggy Shore. The list is long.

I’ve made the assertion that Americans need Ireland. I can only testify to my own experiences of visiting Ireland, the emotional and intellectual impact of the land, the literature, and the people. It’s a place where I always feel welcome. As for the notion of Ireland needing Americans, I remember the words of a toll booth operator, which qualifies as a line of poetry at least to my ears, as we exited the N7 motorway on the way to Limerick. He accepted our two Euro coin, smiled and said, “It’s good to see Americans back.” ♦

ABOUT THE WRITER: California writer, Kelly Candaele traveled to Ireland during the pandemic and found solace in seeking out the landscape of Seamus Heaney’s poetry. Kelly covered the Northern Ireland peace process for the Los Angeles Times. He has written for the New York Times, The Nation, The Guardian and Irish America. He is also a documentary filmmaker.

Leave a Reply