John Lennon stood at the corner of 45th Street and 5th Avenue in New York City and faced the rally. About 5,000 people had gathered that February morning in 1972 to protest the massacre of 13 unarmed civil rights marchers in Derry on Bloody Sunday the week before.

“Any government that doesn’t allow demonstrations like this should be put away,” he told the cheering crowd, reminding them of his Irish ancestry. “My name is Lennon and you can guess the rest.”

It was bright and cold outside the British airline offices where the rally was gathered, and John and Yoko sang their new song, “The Luck of the Irish,” to the demonstrators.

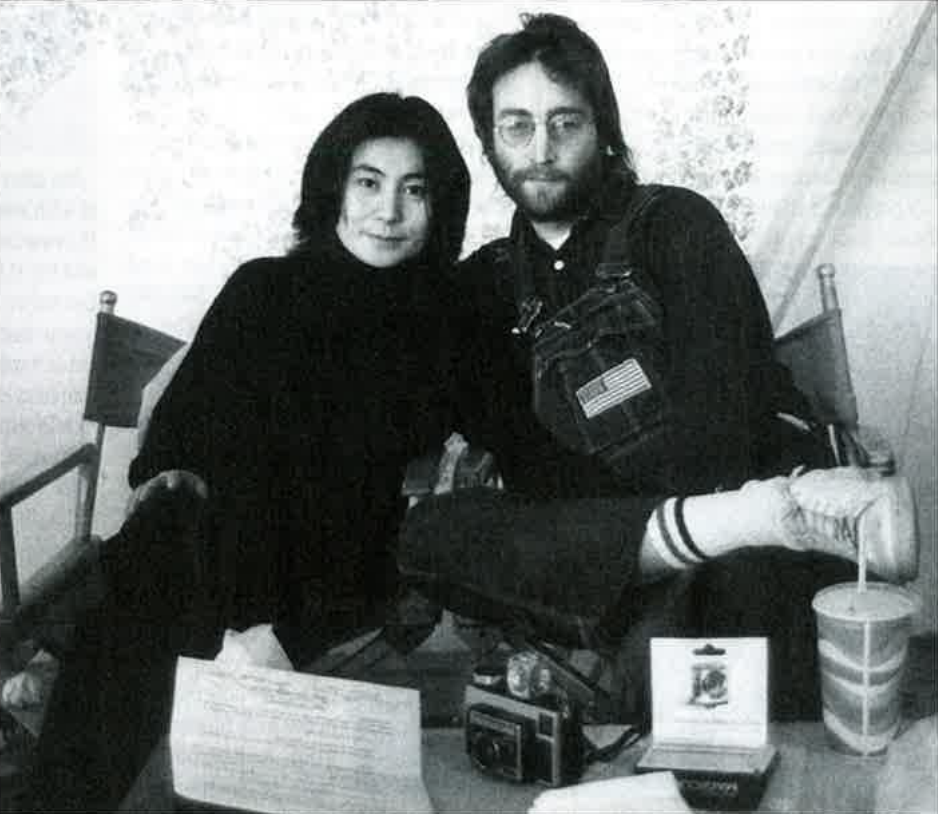

Two days after the protest in New York the rock stars invited Irish American political activists to their home to explore ways they could help the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland.

Ellen and Ron Duncan, Seamus Naughton and Brian Heron of the National Association for Irish Freedom (NAIF), a group closely allied to the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), were summoned to John and Yoko’s apartment on the morning of Tuesday, February 9, and ushered into the famous bedroom where the Lennons sat in the lotus position on the bed.

“It wasn’t a big fancy lavish apartment,” said Naughton. “They had a place in Bank Street in the Village that very few people knew about, a sort of walk-in, basement apartment that was more of a getaway place, a place to relax.”

“It was the biggest bed I’d ever seen,” Ellen Duncan told Irish America. “There was a huge TV at the end of it showing cartoons but with the sound turned off. We had chairs round one side of the bed — we were not invited onto the bed. Both of them looked very fit and agile, and they were also very politically attuned. Him being English, he felt very responsible to do something [about Bloody Sunday].”

She added: “A lot of the conversation was about [him] being Irish from Liverpool and how he identified [with Ireland].”

Lennon was obviously proud of his Irish roots, despite being named John Winston Lennon in a tribute to the British Prime Minister Churchill. His grandfather, Jack Lennon, had been born in Dublin but spent most of his life working as a professional singer in the U.S. (he was an original member of the Kentucky Minstrels).

Paul McCartney had Irish relatives on both sides of his family, and The Beatles had played a couple of gigs in Belfast in November 1963, and another a year later. In 1966, Lennon bought the uninhabited Dornish Island, off the coast of County Mayo, for £1,500 (and a few years later offered it rent-free to a band of hippies who were considering living there).

In August 1971, John and Yoko marched hand in hand at a pro-IRA demonstration in London, Lennon holding a placard that declared “For the IRA Against British Imperialism.” But it was his vociferous opposition to the Vietnam War that made him a target of surveillance by the American authorities, and recently-released FBI files show he was closely monitored by the agency during the second half of 1971 and throughout 1972.

The Nixon administration made strenuous, albeit ultimately unsuccessful, efforts to have him deported before the 1972 election, fearing that he might disrupt the 1972 Republican National Convention.

John and Yoko had been identified with a number of left-wing causes since the breakup of The Beatles in 1970, and their interest in Irish American support for civil rights in Northern Ireland predated the Bloody Sunday massacre. Phone contact between the Lennons and the activists had been going on for some weeks before they actually met, and the couple were familiar with the different Irish American organizations and where they stood politically.

Ono and Ellen Duncan had a one on one conversation during the meeting. “Yoko was very impressed with the women of Ireland at the time — women were very much in the front line, in the leadership,” remembers Duncan. “She spoke about Bernadette Devlin and I told her about Bridget Bond from Derry, Ann Hope and Edwina Stewart…Yoko admired the women on the barricades. She was very interested in developing different tactics to gain the attention of the press, she felt that’s what was needed.”

Naughton also remembers John being interested in the role women were playing in the struggle. “At one stage the talk turned to 1916, and Brian Heron told him how James Connolly had referred to women as `the slaves of the slave’ and he later used that in a song.” (The line appears in the 1975 song “Woman is the Nigger of the World.”)

“They were really concerned about the obvious mistreatment of the minority community and the role of the state in that oppression…NICRA was the organization they’d decided to support,” said Duncan.

The meeting came on a hectic day for Duncan — hours after visiting John and Yoko she flew to Ireland to meet representatives from the U.S. civil rights organization founded by Martin Luther King, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The SCLC had sent a delegation to take part in a NICRA meeting as a gesture of solidarity with the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday.

John and Yoko’s support for the struggle came in the form of money to the Northern Ireland civil rights movement, including proceeds from the “Sunday, Bloody Sunday” song.

Lennon told an interviewer a few months later, “If it’s a choice between the IRA and the British army, I’m with the IRA. But if it’s a choice between violence and nonviolence, I’m with nonviolence. Our backing of the Irish people is done really through the Irish civil rights, which is not the IRA.”

“The Luck of the Irish” was included on the Some Time in New York City album, released in June 1972 along with “Sunday Bloody Sunday.” The songs weren’t classics, and John was disappointed at the negative reaction of disc jockeys to “Luck of the Irish,” which he’d hoped to release as a single.

Much more successful was Paul McCartney’s “Give Ireland Back to the Irish,” recorded two days after the Bloody Sunday shootings which — despite being banned from British radio and TV — enjoyed four weeks in the UK charts and eight weeks on the U.S. Billboard chart.

Naughton paid several more visits to the Bank Street apartment and says the Lennons made a significant contribution to the struggle for civil rights.

“John and Yoko helped to internationalize the situation — it had been mostly the immigrant Irish or first generation Irish who were interested until then,” remarked Naughton. “Then people who weren’t Irish started to get involved.”

This article was first published in the January 2000 edition of Irish America♦

Leave a Reply