When the dust settled on September 11, 343 firefighters were listed as missing, and later pronounced dead. In this excerpt from her upcoming book, Lynn Tierney, then a deputy commissioner at the Fire Department of New York, writes about the difficult task of eulogizing her colleagues.

Eulogies

There came a time in my life, through the autumn of 2001, when I wrote roughly 100 eulogies and edited scores of others. They were in many ways the same, but they were also always different.

I wrote eulogies for close friends and mentors, for senior leaders and legends of the New York City Fire Department. I also wrote eulogies for strangers, colleagues in the 16,000-member FDNY who I came to know only through the posthumous process of piecing together poignant fragments of their life stories.

I wrote through tears and in mind-numbing exhaustion. I worked late into the night in my eighth-floor office at the FDNY headquarters. My view was to the northeast, toward Brooklyn’s industrial skyline. This was a blessing. The smoldering pile of the World Trade Center’s towers, where everyone I wrote about had died on the morning of September 11, 2001, almost in an instant, was to my back, out of sight.

For inspiration, I would play a CD of the soundtrack for “A Long Journey Home,” a documentary on Irish immigration to America. The music had been put together and in parts composed by Paddy Moloney of the Chieftains. I came to realize that this soundtrack – with its soft, sad opening and final flourish, with its musical tensions between mournful bagpipes and lilting flutes, between forlornness and hope, between despair and resolve, in a word, with its Irishness – perfectly matched the emotional thrust and pace of an FDNY funeral oration.

When the fire marshals working down the hall heard music coming from behind my closed door, they knew another eulogy was being drafted. Sometimes they’d interrupt their own grim work – puzzling through GPS data, gruesome photos of bodies, captured radio transmissions, or, more typically, body parts, in an effort to identify the dead – to check on me.

They would ask gently how I was doing: did I want a cup of Barry’s tea? With Splenda, right? They rarely asked who I was writing about; they knew who had been identified before I did.

And they did not linger long.

In that brutal time, small acts of human kindness were treasured. These tea-toting, gun-toting soft-spoken marshals, on many nights, would provide a brief but welcome respite from what had come to seem like a horror movie running on an endless loop.

Nearly two decades later, flickering fragments of the movie still return on almost a daily basis, as vivid and horrible as on the days and weeks, and months that followed 9/11. Chance encounters can trigger them – a building demolition site, with broken concrete and twisted rebar, the smell of wet smoke, the wail of a fire engine siren, even a display of doughnuts in a bakery window.

The night the towers came down, I stumbled, literally, upon a bakery at the lip of the epicenter of oblivion referred to as Ground Zero, or, more commonly among us, as the pile. The shop was just steps from what had been the WTC Plaza. Alone amid blocks upon blocks of wreckage, the bakery remained unscathed, displaying in its window trays of doughnuts decorated with frosting and sprinkles in fall hues. I remember thinking to myself: The world’s tallest towers reduced to a pile of ruin, a steaming, smoking tomb for God knows how many thousands of human lives lost, these doughnuts, these fucking doughnuts, managed to survive untouched.

I am not sure why this still troubles me so, but it does.

There were times in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 when I believed that I was about to go crazy. Years later, I would learn that I had not been altogether wrong in this self-diagnosis. Looking back now, it’s clear that writing eulogies kept me from losing it completely.

After a routinely surreal day of work as an FDNY deputy fire commissioner – duties that entailed everything from standing by relatives when they were informed that nothing more than genetic traces of their missing firefighter had been identified, to escorting dignitaries and celebrities by golf cart to the pile, to attending meetings upon meetings, all different maybe in their agenda, but all essentially devoted to the talk of rebuilding a fire department, and a city – it gave me relief and a certain grounding to write each night in solitude about a heroic colleague.

And they all were heroes.

“I miss the funerals,” I would be surprised to hear Tara Stackpole, a new widow and 37-year-old mother of five, confide to me about one year after the towers went down. “I do, too,” I said.

Neither of us needed to elaborate. Funerals provided us, and for that matter, the entire FDNY family, with a common shelter – a sanctuary from the daily insanity, respite from the dreadful sensation of slowly drowning alone, a safe harbor to grieve.

TALKING POINTS FOR A EULOGY:

Opening Statement: Set the tone by expressing your condolences and the entire departments sense of loss. Single out the member’s spouse, children, parents, and close friends./ Personal Information: Make mention of the member’s character, personality and accomplishments on the job. Consider using anecdotes…. /Statement of Support: Pledge the Department’s full support now and in the years to come for the family.– From an FDNY “Resource Guide.”

Most of the eulogies I wrote were for delivery by New York Fire Commissioner Tom Von Essen, my boss, and close friend. His remarks were but one of many rituals attendant to an FDNY Line of Duty funeral. In the days after 9/11, given the volume we faced, and the questions flying in from the firehouses, we felt compelled to codify these rituals in a guidebook. The book – much of it drawn from existing documents, like the Ceremonial Units Operating Manual, other parts freshly drafted to meet the moment – was distributed to captains to brief them on what to expect as they arranged for services that in normal times would have been staged by headquarters personnel.

The 20-page booklet, a copy of which I keep stored in a plastic bin overflowing with 9/11 artifacts, included a quick “How to Write A Eulogy” section and provided additional practical instructions, such as anticipating and honoring family expectations, coordinating with priests and other service ministers, and adhering to traditions and protocols. For instance, the manual spells out how to carry a casket into the church, escorted by the deceased’s company and borne by eight colleagues: “These persons shall be well-groomed and have a complete and clean uniform. Within reason, all should be approximately the same height…” It was presumed that most services would include a Roman Catholic Mass – for the FDNY in this time was very Catholic, very Irish, and very, very male – although the guidebook lays out rituals for Protestant (Lutheran) services: “Everyone stands for the Apostles’ Creed.”

Most services would include the singing of “Be Not Afraid,” the second verse of which always left me sobbing: “If you walk amid the burning flames, you shall not be harmed….” There would be remarks from the mayor (when he was available), family members, the company captain, and the fire commissioner. “Get the total number of eulogies to be delivered at the end of the Mass and inform the priest.” And, finally, the procession out “Casket goes into the hearse feet first. FEET ALWAYS GO FIRST.”

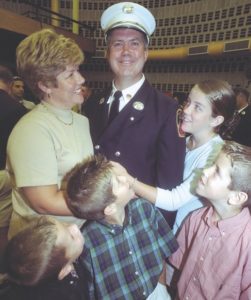

Photo: Roger Smith.

Both the coming and going was accompanied by the FDNY’s Emerald Society bagpipe and drum corps: The muffled drums leading the hearse to the church, the whine of bagpipes playing “Going Home” on the way out: “Once the procession starts the pipers will march for a predetermined time and then peel off.”

In the months following September 11, 2001, these rituals would be repeated more than 343 times, as many families held memorial services if they had no remains, and then later, if remains were identified, a full funeral – a concession by fussy bureaucrats of the Catholic Church following an emphatic discussion with Tom, during which he made clear that under present circumstances the standing rule of one church service per customer must be suspended.

The sheer volume – on one weekend there were 23 distinct services – made it impossible for all the customary dignitaries to attend each funeral. Many eulogies I wrote for Tommy were obliged to begin with an apology: “Before 9/11, the Mayor had never missed a firefighter funeral in all his years in office. But because of these tragic circumstances, he can’t personally be at each service we’re holding.”

If this now sounds a bit defensive, it is important to note that we felt an obligation to give each send-off of a fallen colleague equal weight, whether it was a chief or a “probie,” a rookie firefighter still on probation.

Had we deviated at all from the rituals, the grieving families and their firefighter friends would have noticed. And that would not have been good. There was pain enough to go around, without inadvertently inflicting more.

The eulogies contained common, almost ritualistic elements. At the outset of each, immediate family members would be recognized by their first names. Sympathy and condolences would be offered, not only by the commissioner himself but also on behalf of “the 16,000 members in the New York City Fire Department.”

Almost every eulogy quoted a hauntingly prescient remark. In a speech delivered on Memorial Day, 2000, Chief Pete Ganci said, “We must stand ready to face whatever comes and remember that in this department no one is invincible. At all ranks we contribute, and at all ranks we are vulnerable.”

Ganci was the FDNY’s ranking uniformed office on 9/11, and that quotation made it into his eulogy as well.

In each eulogy, mourners would be reminded why they should be proud of the fallen, be they father, son, friend, or fellow firefighter. Though 3,000 people died, the narrative went, 25,000 people were evacuated on 9/11 to live another day. Just what role the deceased played in assisting the evacuation, of course, could not be known. But this was an exercise in providing comfort, not forensic detail.

“These were wonderful men who loved their jobs, loved their families, and loved each other,” the script intoned. “They will be the stuff of legend and lore in the department for years to come.”

In each, there would be remarks about the outpouring of public support for the department, and expressions of resolve: “People ask me all the time how the department can go on after the losses we have suffered,” Tommy would say. “I tell them that our hearts are broken, but not our spirit.” And each would close with a reminder of the department’s traditional commitment to stand by the families of FDNY firefighters “in good times and bad. We owe them this much at least, and it is a debt we gladly pay.”

Eulogies for department leaders often contained sentiments that now seem a bit maudlin, but in that time these passages reflected an urgent need for any measure of relief against paralyzing pain: “He has gone ahead to make ready the way for those who will follow,” went the eulogy for Deputy Chief Ray Downey, known internationally among fire departments for his strategic innovations in responding to collapsed buildings. “He’ll have the whole place organized by the time everyone else gets there.”

Despite the commonalities, each eulogy was crafted to be personal. This was my responsibility. Before turning on the Irish music, I would interview family members, friends, colleagues – anyone who might know stories or personal traits that could make the fallen come alive again, if only for one final public moment: “Consider using anecdotes.”

And so, to honor Vernon Cherry, the “Singing Fireman” of Ladder 118, a gentle soul who frequently performed the national anthem at official department functions: “We have all heard the story of how Vernon led a group of firefighters in recording a song for a little girl named Crystal Anne Perez, who was suffering from leukemia. He was that kind of guy.”

And Dave Fontana, of Squad One: “Each day of his life was a unique experience. He was a Renaissance man: A reader, writer, sculptor, historian, lover of nature and all things outdoors, as well as loving his wife and little boy more than one can say.”

And Chief Ganci, who would hold court with young firefighters, describing floor-by-floor attacks or mind-boggling rescues from “good jobs,” as they are called in FDNY-speak, from the past: “A cigar, a scotch, a swagger, and a story. How many of us in the room have not been involved in that act?”

Some of these eulogies were more difficult to write than others. One, for me, was impossible.

From the start of my tenure, my mentor had been Chief Bill Feehan, the first deputy commissioner, and the department’s sage and historian. At his morning coffee klatch, an event I tried never to miss, he would sit behind his desk and, speaking in his New York parlance, parcel out pearls of fire department wisdom and weave spell-binding yarns from memorable FDNY feats.

To me, though, he was much, much more – a loyal friend and personal tutor. Beyond department protocols and history, Bill patiently tried to instill in me an appreciation for its soul. He sensed rightly that, when it came to falling in love with the FDNY, I would be an easy catch.

“Lynn,” I remember him telling me early on, “people in this city don’t understand what makes our guys tick. They are complicated. You need to let New Yorkers know, more than anything, these guys signed up to help them. You need to let them know why these guys run in when others run out.”

“Listen Kiddo,” began another bit of tutelage, “when you drive to a fire scene, kill the siren a few blocks away so you don’t come screaming up the street like a buffed-out nitwit. And make sure you don’t park anywhere near a fire hydrant. The guys will punch out your windows and run a line right through the car if they need to take a hydrant, and they don’t care who owns the car. In fact, they probably dream of doing it to a boss’s car someday.”

“Look,” he would frequently admonish, “I can only guess how hard it is to be a woman in this department. They have been brutal to some of the female firefighters. You have to be strong and set an example, as a female leader. Remember, I’ve got your back if anyone gives you any crap.”

Among other skills, Bill taught me how to craft eulogies for Line of Duty funerals – the telling anecdote, the soaring flourishes, the final notes of support and resolve: “It’s up to you to make it real and heartfelt. It has to be, because even if we didn’t know him well personally, we know him. We know what he was about and what his death means.”

After 9/11, Bill’s was one of the first eulogies ready to be drafted. I did not even try. It was more fearing the emotions that the process would unleash. It was also that the act of composing the remarks would confirm that this lovely man had died, and I wanted, beyond reason, to believe he was still with us.

These days I start each morning with a sprightly local paper, the Bangor Daily News. One day I might be captivated by the account of a jogger who, with the fangs of a rabid raccoon sunk deep into her thumb, had the presence of mind to drown the creature in a puddle. Another I might clip for future reference: A how-to guide on cooking beans in a freshly dug bean hole.

Most days, though, I move quickly through the news reports and advice columns and make my way to the obituary page. Here is where my reading slows down. Here is where I linger.

I read about Jeannette, known for her love of baking, especially making whoopie pies for her family. One of my favorites was about Theresa, written by her funny family who entertained her in her last days. It began, our mother hoarded butter. I read about Robert, a Pearl Harbor survivor who was a master of his favorite pastime, conquering the Bangor Daily crossword puzzle. And Irene, whose “famous” clam chowder drew people to church suppers every time.

In short, I read not about deaths, but about lives, lives captured in a few hundred words by the family members who submit these lovingly crafted tributes for publication. This daily habit tends to make me melancholy, returning me to those late nights with Paddy Moloney’s CD playing and me at the keyboard, trying to do just what these next of kin, driven by love, respect, and resolve, have tried to do – to bring back a loved one, to bring back family.

“Because the fire department is such a huge family,” went another stock line from the 9/11 eulogies, “…we’re really feeling each individual loss as we say goodbye to our treasured friends. When we lose a member of this department, it’s as if each of us loses a little bit of ourselves.”

Rereading that passage today, I must admit I have no earthly idea why I inserted the modifier “little” into the final sentence. Among the survivors, a lot more than a little bit of us was lost on that September morning.

There are reasons why, all these years later, I’m still struggling to put my 9/11 experiences to paper. Many times over the years, I have rededicated myself to finishing a memoir of that day and all that followed. Then distractions take hold. Or I lose confidence, afraid that I have nothing to offer. Bodies fell all around me that morning. I was engulfed and nearly suffocated by the tsunami of ashen debris that swept through lower Manhattan. But, in the end, I survived, and from an FDNY perspective, the story of 9/11 belongs not to those who lived but to our 343 colleagues who did not.

I might also note that I have been diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, depression, anxiety, and a few other mental maladies. Anyone who has spent 15 minutes with me can attest that I also am inflicted with Attention Deficit Disorder. In my dreams, and sometimes even in wakeful moments, I am visited by ghosts of the fallen, which presumably qualifies as some distortion of reality.

What I can state with confidence is that this memoir is not meant to be cathartic. I have not found “closure,” and I am not looking for it now. In fact, I do not believe in closure. I do believe in the ghosts.

In part, I suspect my writer’s block, if you could call it that, mirrors my instinctual decision to not even attempt a draft of Bill Feehan’s eulogy: I know too well what happened on September 11, 2001. It is seared into my consciousness. But part of my life since has been a struggle to keep it from being the dominant center of my existence.

Nobody owns 9/11. It was an event that burned into the souls of people across the land, even around the globe. Everybody touched by it has their own memory reel, their own catalogue of emotions. This is not only true for the surviving children who for 20 years have watched family members murdered by terrorists over and over again on television (Dad, I don’t want to see this movie anymore, a California friend recalls his terrified young son telling him late in the afternoon) it is also true for those who found themselves trapped on the street that September day, in the swirling Manhattan madness.

I played no great heroic part in any of it. I simply was there. I simply, or maybe not so simply, survived. With my survival comes an obligation: to tell what I know about the people who truly were heroes that day, to convey as clearly as I can, the character of the firefighters who lugged their equipment up those tower stairwells that morning, and never came back down, to portray the struggle of the survivors I came to know – the widows, the mothers, the fathers, children, all of them – who have spent the last two decades trying to stitch back together their shattered lives.

So, for openers, let me just say this about the FDNY firefighters I encountered in my six years as deputy commissioner: Firefighters, I came to know, are goofy, impossibly funny, and outrageous. They act out like teenagers and attack fire like warriors. They are smart as hell, bull-headed, innovative, determined, and loyal. They are aggravating and endearing. They can be kind. They can also be nasty, mean, and small, and I have the anonymous hate mail to prove it. The firefighters I knew could get furious about matters big and small. They tended to pontificate, yet they also would listen to anyone with an idea that might help them more effectively battle smoke and flame. In short, they were layered, complex, and human, just like the rest of us. And, as a breed, they stood apart.

It took me some time to accept it, but eventually, I grasped that the same juvenile naiveté that drove our firefighters to play outrageous pranks on one another and drunkenly plunge into public fountains on St. Patrick’s Day, was but a turn of the same screw that allowed them to charge into high-rises engulfed in flame to rescue people.

We needed them to be a little crazy. We needed it on 9/11. We need it today and every day.

It is for them, for all New York City firefighters but particularly for the 343 who lost the chance to tell their own story that I took on this job. It is for them I keep coming back to the keyboard, false start after false start, telling myself each time:“Be not afraid.” ♦

Visit Irish America’s April/May 2002 issue to read stories of love, courage, and kindness from 9/11/2001.

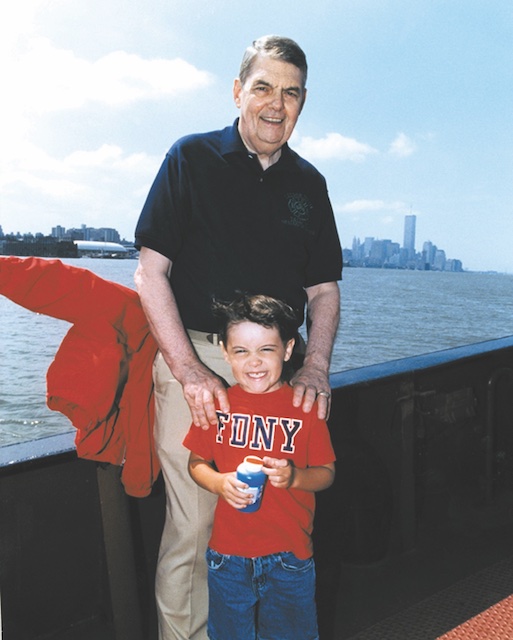

ABOUT THE IMAGES: Peter Foley, who took many of images for this feature, was one of the first photographers to arrive at the site of the World Trade Center on 9/11 – just after the 2nd tower collapsed. In the weeks and months that followed, Peter continued to document both the recovery effort and memorial services. It was a personal undertaking for him. Prior to 9/11, he had spent three months documenting life in the Firehouse of Engine 54, Ladder 4, in Manhattan, which lost 15 of its members on 9/11. Today, Peter is a contract photographer for the European-based wire service European Pressphoto Agency.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: I was part of a team charged with writing FDNY eulogies after 9/11. Writers from the FDNY, the Mayor’s office, volunteers, and friends, all contributed.

Thank you for your company coming to my rescue! The firefighters that have been lost on 9/11 and the firefighters that have been lost since do not deserve to be gone now! My love and condolences go out to all firefighters lost or still remain standing today. It’s weird that the writer has so so much in common with me my name is Christopher hiltz. I am from hingham Massachusetts. My father john hiltz. Sr who is missed by so many was my life my love and best friend. He passed away the end of march 2021. I have much love for this earth rrrqand it is just being destroyed right infront of my eyes! Thank you for helping me get my life back! I’ve never felt so loved and cared for since the loss if my father. Thank you and god bless!

Lynn Tierney, you are a wonderful writer. Your heartfelt obituaries to these extraordinary heroes are so obvious.

Stay well and enjoy your retirement.

Lynn,

Great article. Hope you are well.

Dan Lynch

Former UFA Board member

Retired FDNY