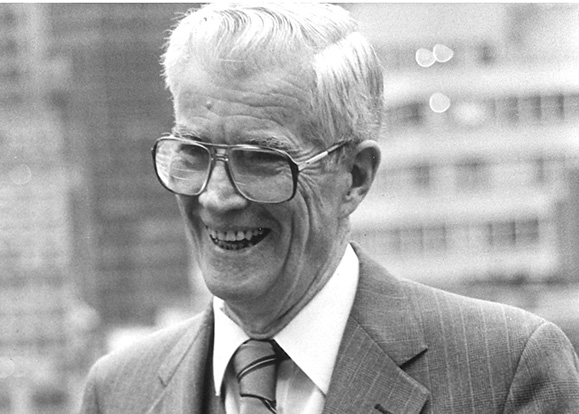

His birthplace claimed by two states, Jeremiah Curtin, son of Irish immigrants, shed glory upon the state to which he was brought as an infant — Wisconsin.

Something of his indomitable nature was evident in his triumph over frontier conditions to become the first Wisconsinite to earn a degree from Harvard College and to go on to become one of the greatest linguists the world has ever known and an ethnologist of the highest quality.

Of international reputation, he had the facility of 70 languages and dialects, including most European languages, several Asian, and many American Indian tongues. He was not boasting when he said, “There was always some language I wanted to learn.” His passion was based upon his conviction that language was the amber in which thought and social custom were preserved.

Remarkably in advance of his time, the direction of his interest in languages is implicit in his statement: “…My object being to go as far back as possible in the history of human thought.” To go back as far as possible places a special value on the language, myths, and customs of primitive people and their manuscripts, artifacts, and monuments that have survived. A comparative study of other and earlier societies would enlighten us about our own. This is the reason he mourned the extinction by the Europeans of so much of the language, customs, and monuments of the aboriginal peoples of North and South America. The effect was tantamount to the loss in an octogenarian of decades of his younger years.

“When the Western Hemisphere was discovered,” he pointed out, “North and South America contained the most varied and most extensive museum of the human mind in its earlier conditions that the world had ever seen.

“It is evident,” he continued, “that what they [the aboriginese] held in their heads and what they had to show to investigators of their social and political institutions were of vastly more value to mankind than anything else connected with them…”

Such a view is not obvious without a reminder of the benefits modern agriculture, pharmaceuticals, and psychology have received from primitive societies.

Curtin’s insatiable concern about the structure and content of all and any conglomeration of people is that which makes them uniquely human. As an ethnologist he recognized language as the treasury, the transmitter, the myth maker and molder of societies.

The yearning to understand human motivation sent him scurrying around the world squeezing the essence out of human expression, whether it be Mongolian, Shawnee, or Russian.

He became an intrepid traveler, enduring extraordinary hardships, as he rescued the myths of vanishing societies, such as the Irish, American Indian, or Mongolian, by learning their languages, and collecting and publishing their tales.

As a translator he brought the works of Tolstoy, Sienkiewiecz, Zagotsky, and other Slavonic writers to an English audience. Similarly with tales from Indian, Gaelic, and other sources. On a more day-to-day practical basis he served as a translator in the American Legation in St. Petersburg, Russia and in other mundane areas.

In his function as Secretary to the Legation he incurred the displeasure of Cassius Clay, the Minister who once described him as a “Jesuit Irishman.” The term Jesuit, of course, was code for Catholic and meant to be more abusive, perhaps, than Papist in 19th century anti-Catholic reference. Clay knew Curtin to be American by birth but used the word Irishman in that sneering manner common among Anglophiles of the period.

Curtin was not embarrassed by his religion or his ethnicity and, drawn by his meeting with a few Irish speakers in the U.S., determined to learn Gaelic, both Irish and Scots. The fact that there was a significant body of lore, including manuscripts, older than anything corresponding in English (or Anglo-Saxon) excited his scholarly mind. He decided to go to Ireland.

He made two trips, the first lasting a bit short of four months, the second one 22 months. With an outgoing personality and a keen, analytical mind, nothing was lost on him. He made overtures to strangers, asked questions, knocked on doors. He had provided himself with letters of introduction to scholars who, in turn, were pleased to supply further introductions.

On most of his investigations he was accompanied by his wife who performed as secretary. Travel in Ireland a century ago, especially to the less developed areas (of greater interest to Curtin) was onerous. Stagecoach and side-car, rain or shine, substandard accommodations in the outlying areas were the norm. But 26 months (total) in Ireland gave him an intimate view of the incredible poverty and the evils of the British system in Ireland.

It also provided him with several volumes of translations from Gaelic speakers, some of which would have disappeared forever but for his recording them.

His bent, of course, was scholarly, a reconstruction of the ideals of “pagan” societies before the time of Christ or shortly afterward. He had no time for stories “to amuse travelers.” He was amazed at the quantity and quality of ancient manuscripts at Trinity College Library and especially at the Royal Irish Academy.

“Neither in ancient nor modern times had any nation such a collection,” he wrote: a tribute to the glory of Ireland’s early achievement and a stark contrast to contemporary Ireland.

After 26 months he left on a Requiem note. He had returned to County Kerry, especially Cahirciveen “for there were men there who spoke their own language.” But he found a conversation with a young woman disconsoling. He had commented on the boon that one’s own historic language was. She replied that Irish could be spoken only in Ireland “and it is too common in itself.”

So we leave frontiersman Curtin who, in the words of Joseph Schafer of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, “has long been recognized as one of the greatest practical linguists; also a mythologist, a student of primitive cultures whose works are in high repute among scholars in the social sciences.”♦

Leave a Reply